Definition and Scale↑

The term “rear area” (German: Etappengebiet, French: zone des étapes, as a part of the zone des armées) refers to the area between the frontline, or “operational zone”, and the more remote home territory. Its primary task was that of securing supplies for the fighting army, both of men and material. Via this area, fresh troops were brought to the front, and wounded as well as prisoners of war transported back. The military personnel in the rear also had to provide billets and provisions for the passing troops, secure the communication and transport lines, and organize and administer the occupied areas on enemy territory.

The rear areas on the Western Front comprised Belgian and French territory. Although Belgium was almost entirely occupied by German troops, and, from August 1914 onwards, administratively organized as the "General Government of Belgium" (Generalgouvernement Belgien), about one-third of Belgian territory in the west and in the south remained German Etappengebiet. Only a small part of western Flanders was held by the Allies, stretching roughly from the Belgian/French border near Armentières to the sea, including Nieuwpoort. Here, French and British armies were operating side by side.

In France, ten northern and north-eastern départements were partially or fully occupied by German troops, meaning about 4 percent of French territory. Almost all of German occupied France officially remained “Operations- und Etappengebiet” (operational and rear area) until the end of the war. On the other side of the frontline, the army zones (including the rear) were under French and British command.

Soldiers’ Lives in the Rear↑

Concerning soldiers’ experiences, many characteristics, routines and problems of the rear were the same on all sides. On the one hand, soldiers came here to recover from combat, or from exhausting and often dreary trench duty. Several opportunities were provided to distract them from the cruel realities of war, such as theatres, cinemas, sports, and libraries. Also, there were (obligatory) bath and delouse facilities, so that soldiers could get rid of dirt and vermin of the trenches.

Because of the stalemate on the Western Front and the long duration of the war, many soldiers stayed in one place for a long time. Therefore, they came into closer contact with the inhabitants and even experienced a sense of home, or at least cherished the illusion of “normal life”. Relationships were especially close with local children, who possibly reminded soldiers of their own sons and daughters or younger siblings. In this way, for soldiers, the rear constituted an island of calm and peacefulness that stood in sharp contrast to the horrors of war.

On the other hand, soldiers often dedicated their leisure time to heavy drinking and visiting brothels, so the army commands were anxious to keep them busy and fit for the front. For this purpose, soldiers were subjected to drills and exercises, which they, overall, loathed and about which they complained much in their diaries and letters.

In general, there was much potential for conflicts in the rear. First of all, iniquities caused by the army hierarchy became blatantly visible “on leave”. Officers were much better billeted and got better food rations than the “simple soldiers”, they had their own quarters for eating, drinking and socializing (the Offizierskasino or officer’s mess/ mess des officiers), and, at least in the German and British cases, they even had their own brothels. There were, however, also tensions between the rear staff and soldiers who had to return to the frontline after some days or weeks of recovering. The longer the war went on, the more the active soldiers despised their comrades on rear duty, whom they accused of shirking.

Apart from these internal conflicts in the armies, external ones also existed, relating to the fact that military and civilian spheres collided in these areas.

Civilians’ Lives in the Rear↑

While for soldiers the rear was primarily a zone for recovery and repose, for civilians it was quite the opposite. For the inhabitants of the rear zones, it meant a radical break with their pre-war daily routine, as they were affected by the immediate consequences of war, and, especially in the German case, suffered multiple privations and military oppression.

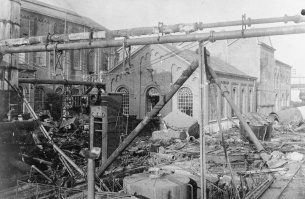

On both sides of the front, towns and villages in the rear suffered under regular air bombardments. The Allies had the dilemma that when they struck at the enemy in these zones, they often killed or wounded French and Belgian civilians. The civilians were resentful about these incidents of “friendly fire”, while German authorities used them for propaganda purposes, thereby trying to distract from the fact that they did the same, and, moreover, destroyed parts of occupied France in a “scorched earth policy” during their strategic retreat to the “Hindenburg Line” (Siegfriedstellung) in 1917.

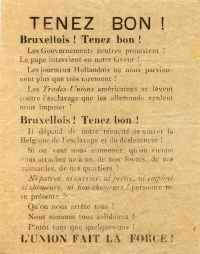

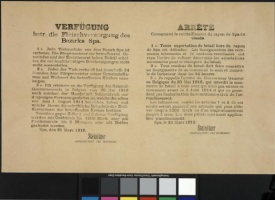

In general, civilians in the rear had to endure the militarization of their daily routine. The local population had to submit to military command, open their homes to soldiers billeted in their towns, and provide all goods and material demanded for the upkeep of the troops. Moreover, army commanders were especially concerned about the safety of their troops within this sensitive area behind the frontline. Fear of espionage was omnipresent, and the inhabitants were subjected to curfews and restrictions on mobility. Thus, even though many soldiers maintained amicable relations with the local population (which even held true for the German Etappengebiet), there were also several causes for friction.

According to the logic of the military, the civilians in the army zones were primarily a burden. British army commanders, for example, endorsed forced evacuations of whole villages, because they wanted more room for their troops and feared that civilian refugees would jam the streets when leaving their homes in panic. In their treatment of the population, they, however, had to take their French ally into account. Therefore, the protests of the local authorities could not just be ignored.

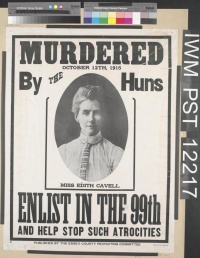

The German army commanders, on the other hand, had no such obligations, as they were operating on enemy territory. They not only carried out forced evacuations from the combat zone, but also resorted to deportation as a deterrent and punishment. Many thousand civilians were brought to camps in Germany or moved within the occupied territory. In general, the population suffered under a particularly strict regime of occupation. The occupant basically relied on a principle of deterrence, threatening harsh penalties for all kinds of infractions, and heavy punishments were often carried out to make an example.

All in all, the German occupation policy was driven by the efforts of German military, political and economic leaders to exploit all occupied territories for the German war effort. While armies traditionally drew on resources on site and partially lived "off the land", the economic exploitation of German occupied territories, including the rear zones, was unprecedented in scale. Moreover, the German military occupiers resorted to compulsory labour from the beginning to obtain urgently needed manpower, and soon relied on a system of "force and inducement" that developed its own fatal dynamic.

Even though tensions between the army and population existed on all sides, the situation was especially precarious in the German Etappengebiet. Here, military rationalism could follow its own logic, almost unhampered.

Conclusion↑

In general, the rear area can be summarized as a unique front in between the home front and the military front, where not only soldiers and civilians, but also "national enemies", came into contact on a daily basis. On all sides of the front, this area was characterized by conflict and harsh living conditions for the local civilians, who had to submit to the needs and claims of the army. While the exploitation of resources and manpower for the upkeep of troops on enemy territory conformed to war custom, the German policy far exceeded this practice. As did all the other territories occupied by Germany, the Etappengebiete on the Western Front soon served the sole purpose of sustaining the German war effort.

Larissa Wegner, Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg

Section Editor: Emmanuel Debruyne

Selected Bibliography

- Becker, Annette: Les cicatrices rouges, 14-18. France et Belgique occupées, Paris 2010: Fayard.

- Connolly, James E.: The experience of occupation in the Nord, 1914-1918, Manchester 2018: Manchester University Press.

- De Schaepdrijver, Sophie: La Belgique et la Première Guerre mondiale, Brussels 2004: Peter Lang.

- Gromaire, Georges: L'occupation allemande en France (1914-1918), Paris 1925: Payot.

- Hirschfeld, Gerhard / Krumeich, Gerd / Renz, Irina (eds.): Die Deutschen an der Somme 1914-1918. Krieg, Besatzung, verbrannte Erde, Essen 2006: Klartext Verlag.

- Makepeace, Clare: Male heterosexuality and prostitution during the great war. British soldiers' encounters with Maisons Tolérées, in: Cultural and Social History 9/1, 2012, pp. 65-83.

- Nivet, Philippe: La France occupée, 1914-1918, Paris 2011: A. Colin.

- Salson, Philippe: L'Aisne occupée. Les civils dans la Grande Guerre, Rennes 2015: Presses universitaires de Rennes.

- Schwarte, Max (ed.): Die Etappe, volume 7, Leipzig 1923: Barth, pp. 198-272.

- Wegner, Larissa: Besatzung, in: Pöhlmann, Markus / Potempa, Harald / Vogel, Thomas (eds.): Der Erste Weltkrieg 1914 - 1918. Der deutsche Aufmarsch in ein kriegerisches Jahrhundert, Munich 2014: Bucher, pp. 159-183.