Combat Rations↑

The fundamental purpose of combat rations was to efficiently provide soldiers with enough calories to fulfill their duties. The rations supplied to the men of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) provided between 3,000 and 4,000 calories per day, versus the 2,000 deemed adequate for the civilian population. Although calorically sufficient, soldiers often complained about the lack of variety found in official military rations. One of the most common foods was canned corned beef, colloquially known as “Canned Willie.” American soldiers routinely ridiculed this cornerstone of U.S. Army rations, as well as the corned beef hash, which was derided as “slum.” Sometimes American soldiers received French army rations, which typically consisted of black bread and tinned beef from Argentina. American soldiers were equally critical of these rations, their foreign nature often making them harder to stomach. Despite the ubiquity of complaints, members of the AEF tended to fare far better than their Entente counterparts and even received on average 1.5 pounds of candy per month.

Soldiers of the AEF received their rations in a variety of ways. Mobile field bakeries offered the possibility for soldiers to receive relatively fresh bread. The mobile Liberty Field Kitchen was in universal use by 1918, thus allowing cooks to prepare warm meals. Hot rations of stew, coffee, and the like were drawn in either 2.5 or five-gallon cans. Later in the war, U.S. forces adopted the French Marmite Norvegienne to transport rations up to soldiers because of the vessel’s insulation, which ostensibly helped to keep the contents warmer. However, the nature of trench warfare, coupled with inclement weather and problems in coordinating supplies, often made getting warm meals up to the front difficult, if not outright impossible. Soldiers typically carried both reserve rations and tinned emergency rations to the front to sustain them, given the probability that regular rations would not reach them.

Logistics of Supply↑

The United States Army Quartermaster Corps faced two interrelated logistical problems when it came to feeding the AEF. The first resulted directly from the unprecedented quantities of foodstuffs required to sustain the millions of young men called to arms. The vast distance rations had to travel compounded this issue: first across the United States, then across the Atlantic to Western Europe. Upon arrival in France, rations were sent from base depots near port to intermediate depots, then off to advance section depots before going up the line - all along an already over-strained rail and road network.

Military planners were tasked with obtaining requisite foodstuffs without disproportionately affecting the U.S. civilian population back home. Shortages in Europe meant that the AEF could not rely upon local procurement. To help alleviate this, the Quartermaster Corps established the Gardens Bureau in 1917, which allowed American soldiers in France to raise their own gardens. This helped soldiers obtain much needed produce while adding extra variety to their standard diet. Planted on over 1,500 acres behind the lines, these gardens produced nearly 7 million pounds of fresh vegetables in the summer of 1918.

The home front also played a central role in supplying soldiers with foodstuffs, especially consumable luxuries that many had grown accustomed to back home. In addition to augmenting diets, the goodies sent in care packages from loved ones symbolized that soldiers’ sacrifices did not go unnoticed. Philanthropic organizations bolstered soldiers’ supplies with treats that were deemed to be morally preferable, including chewing gum, soda pop, coffee, chocolate, and cigarettes, often at canteens near the front. Some organizations gave their wares to soldiers free of charge, while others charged for them. The variance in practices, let alone prices, was often a point of contention amongst soldiers. The shipments of these goods to the front were subjected to comparable logistical hurdles as official rations.

Home Front Food Control↑

While not faced with the same chronic food shortages as their European counterparts, the strains of war forced Americans to alter their consumption patterns in varying ways. Long before the U.S. declaration of war on Germany, prices of global commodities and foodstuffs had rapidly increased, straining pocketbooks across the nation. After April 1917, the U.S. government was faced with the problem of how to concurrently feed its citizenry and the massive army it sought to field, all while maintaining food export commitments. The Food and Fuel Control Act – or Lever Act – which Congress passed on 10 August 1917, was intended to alleviate these issues without imposing formal rationing on the civilian population. Consequently, price fixing was employed in an attempt to cap excess profits, curb price speculation, and limit domestic hoarding.

Price fixing, however, wrought its own sets of problems. One main issue lay in how to entice food producers to increase production and guarantee profits without simultaneously gouging consumers. One incentive programme was the provision of low-interest loans to help farmers increase production in light of ever-expanding demands. However, the increased consumption of one product as a substitute for another could have a ripple effect on the availability and price of other food resources. This is exhibited in the relationship between cornmeal and pork consumption. Americans were urged to forgo wheat, which was needed to bake bread for the AEF, and use cornmeal instead. Herbert Hoover (1874-1964), president of the U.S. Food Administration, also issued a national plea for Americans to use more pork products and save beef and butter for military use. Yet, in 1917 farmers became increasingly reluctant to raise more hogs because the increased domestic demand for cornmeal, the traditional feed used, had caused the price to triple.

The Obligation of Patriotic Sacrifice: Self-Rationing and Increasing Food Production↑

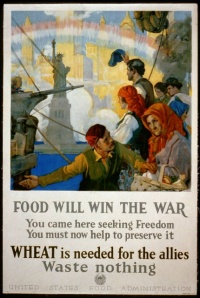

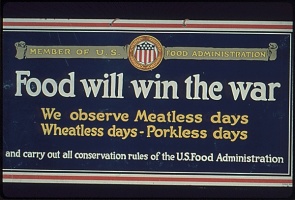

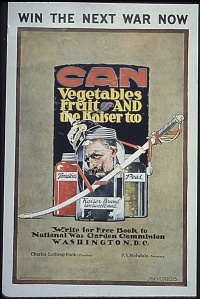

The central goal of the U.S. Food Administration was to encourage citizens to limit individual consumption of vital foodstuffs without enacting government dictated rationing. This campaign ran in conjunction with one that targeted food producers to provide as much food as possible for the war effort. Central to these operations was demonstrating that self-rationing and increased food production were inextricably linked to national duty. These efforts were portrayed as a collective endeavor, requiring sacrifice by all Americans in order to achieve victory. As such, Americans were to become more efficient consumers and producers in light of the widespread burdens imposed by the conflict. Citizens were taught a variety of methods for how to limit their portion sizes and reduce waste, the latter of which was believed to concurrently alleviate food shortages while militating against strains in transportation. Americans were increasingly urged to forgo various mealtime staples during weekly and bi-weekly “meatless” and “wheatless” days. Canning was touted as not only a more efficient way to conserve food, but also a patriotic obligation.

The discourse employed reflected the belief that domestic food conservation was central to national security. Placards imploring citizens to reduce consumption of sustenance and luxury foodstuffs became a common sight across the country. In many cases, these visual reminders served as teaching tools, instructing Americans what products could be used as substitutes for the staples needed in Europe. The Food Administration also posited patriotic self-sacrifice as a way for all to take an active role towards achieving victory. Many posters equated saving essential products as “serving the cause of freedom.” Others literally linked combating food shortages with defeating the Kaiser. In the process, many Americans became active participants in “self-policing,” conducting grassroots surveillance within their communities to ensure compliance with food control measures. Those that did not adhere to these patriotic obligations were summarily punished, either through public shaming or by being reported to local authorities.

Americans were urged to contribute to this effort beyond merely conserving food. Those that were able-bodied were encouraged to volunteer at their local farms to help bring in the harvests. Another scheme that was propagated was the so-called “war garden.” Later dubbed “Victory Gardens,” these plots were seen as a way to buttress local supplies while concurrently conserving vital resources. Citizens were instructed to “sow the seeds of victory,” and by doing so they could fight the increased cost of living and the Kaiser simultaneously. Gardens were planted both residentially and in community-wide cooperatives, with roughly 3 million sown by December 1917. This number soared to 5.25 million the following year. Gardeners were touted as “soldiers of the soil,” and the plots they tilled were extolled as “backyard munitions plants.” Some placards even proclaimed that “food is ammunition: don’t waste it!”

Consequences and Implications↑

Adjustments in food procurement and consumption during the war affected American society in myriad ways. Domestic consumption decreased approximately 15 percent by the end of the war, while U.S. food shipments overseas tripled over the same period. Increased conservation inspired new technological methods, notably in the realm of food preservation. Women, who played a central role in ensuring that their families and neighbors adhered to the volunteerism propagated by the Food Administration, saw an increased role in public and political life. Across the country they taught classes, signed pledges, displayed banners, and policed their neighborhoods in pursuit of collective self-sacrifice. However, as most scholars agree, the expansion of available foodstuffs was not wholly the result of civic volunteerism. In most cases, these increases were directly related to American farmers responding to available profits, which were driven by the concomitant effects of international food shortages and price inflation. In many instances, enticed by low-interest loans, local farmers went increasingly into debt in order to reap potential profits while trying to help meet demand. The levels of this debt were compounded during the Great Depression, further expanding the impact of the global financial collapse to American food production.

Robert Shafer, Pennsylvania State University

Section Editor: Lon Strauss

Selected Bibliography

- Broadberry, Stephen N. / Harrison, Mark (eds.): The economics of World War I, Cambridge; New York 2005: Cambridge University Press.

- Capozzola, Christopher Joseph Nicodemus: Uncle Sam wants you. World War I and the making of the modern American citizen, Oxford; New York 2008: Oxford University Press.

- Eighmey, Rae Katherine: Food will win the war. Minnesota crops, cooks, and conservation during World War I, St. Paul 2010: Minnesota Historical Society Press.

- Fisher, John C. / Fisher, Carol: Food in the American military. A history, Jefferson 2011: McFarland & Co.

- Nash, George H.: The life of Herbert Hoover. Master of emergencies, 1917-1918, New York 1996: W.W. Norton.

- Offer, Avner: The First World War. An agrarian interpretation, Oxford; New York 1989: Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press.