Siberia to St Petersburg↑

A Legend is Born↑

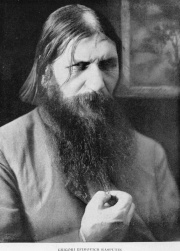

Little is known for certain about Grigorii Rasputin (1869-1916). The gaps created by a lack of reliable sources have been filled by a torrent of gossip and myth-making that has seen him hailed as prophet and healer or impugned as a dark force responsible for the destruction of the Romanov dynasty. Confusion and controversy shroud such basic details of his life as his date of birth and origins of his name. The birth date of 23 January 1869 was recorded by a local registry but alternative suggestions range from 1860 to 1873. His daughter Maria claimed he was born in 1871 as a fiery meteor appeared in the sky. The chief investigator of the Extraordinary Commission of Inquiry set up by the Provisional Government in 1917 to examine the relationship between Rasputin and the deposed imperial family gave a birth date of 1864 or 1865, possibly overestimating Rasputin’s age at death on account of the effects of heavy drinking on his body. He was born in the village of Pokrovskoe in western Siberia into a peasant family relatively well provided for by his father’s work as a driver. Some works assert that the surname Rasputin was bestowed on the family to indicate a dissolute character due to its similarity to the Russian word for debauchery, rasputstvo. It may, however, have simply derived from the word for crossroads, rasput’e.

Route to the Tsar↑

Some time after his marriage, Rasputin departed Pokrovskoe to spend three months at the Verkhotur’e monastery. According to some accounts, Rasputin, prone to spiritual visions from childhood, was inspired to devote himself to God by an encounter with a priest or theological student as he was driving in his father’s cart. Fellow villagers, however, testified to the Provisional Government’s investigator that Rasputin left to avoid trouble following accusations of theft. After his time at the monastery, he learned to read Church Slavonic and made pilgrimages across Russia, wandering as far as the churches of Kiev and the monasteries of Mount Athos in Greece although returning home often enough to father three children. He gained a reputation as a holy man, or starets, a figure holding no formal position within the church but credited with religious insight and the ability to calm souls, though not everyone was convinced of his holiness. The Pokrovskoe village priest accused him of blasphemy and membership of the khlysty cult, whose adherents held that sin was necessary to achieve unity with God. No proof emerged of Rasputin’s involvement with sects, although he did advocate a philosophy of redemption through sin, especially to the female followers he seduced. The whiff of scandal did not prevent him acquiring admirers among the upper reaches of the clergy and nobility, including the bishops of Saratov and Kazan and two grand duchesses, daughters of the king of Montenegro, who, in 1905 and 1906, presented their man of God in the Russian capital to the Tsar and his wife, Aleksandra, Empress, consort of Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia (1872-1918).

Power and Influence↑

Powerful Friends↑

In Saint Petersburg, Rasputin’s intense stare, coarse peasant manners, romantic tales of the Russian landscape and air of spirituality caused a stir among a social elite eager for distraction from the unsuccessful war with Japan and popular uprisings of 1905 and he attracted a circle of well-placed ladies and political adventurers. His intimacy with the imperial family was cemented by his ability to halt the bleeding of the haemophiliac heir, Tsarevich Aleksei Nikolaevich (1904-1918). The power of Rasputin to induce a recovery in the boy was confirmed by a number of witnesses. It may have been coincidence that the starets arrived on several occasions just as a haemorrhage exhausted itself. Alternatively, Rasputin’s calming presence and possible hypnosis skills may have relaxed Aleksei enough to reduce the blood pressure. What matters is that Aleksandra, devout in her adopted Orthodox religion and inclined to mysticism, believed her son owed his health to Rasputin’s prayers. The reliance of the imperial couple on his healing, coupled with their isolation from the court, distrust of official Russia and belief in the devotion of the Russian peasantry, meant they persisted in receiving their friend Grigorii even when presented with scandalous reports of his behaviour in bathhouses and gypsy bars by ministers and security chiefs.

Wartime Influence↑

As news of Rasputin’s closeness to the sovereign spread, the stream of petitioners making their way to his lodgings in the capital swelled. In his waiting room businessmen seeking contracts and well-dressed ladies seeking advancement for their husbands mingled with peasants seeking charity, pardon or exemption from military duty, Jews seeking residence permits and nuns waiting to be blessed. According to the standard account of Rasputin’s political role, his influence reached its apogee during the First World War when the Tsar took over as Commander-in-Chief at the front, leaving his wife and Rasputin to preside over a succession of disastrous ministerial appointments, notably the elevation of their protégé Boris Vladimirovich Shtiurmer (1848-1917) to the position of Prime Minister. Dominic Lieven, however, has argued that despite endless stories of Rasputin’s peddling of top government posts and meddling in policy arenas from food supply to relations with Russia’s parliament, the Duma, and even military strategy, there is no evidence he had a significant political role outside of church affairs. His influence was exaggerated by society gossip and his own drunken boasting. Decisions put down to Rasputin’s interfering can be explained in other ways. The frequent wartime reorganisations of government that came to be known as "ministerial leapfrog" and appointments of men who were, at best, incompetent for high positions can be accounted for by the small pool of administrators who were champions of the autocracy and also able to work with the Duma. There are plenty of examples, moreover, of occasions in which the Tsar pursued a course opposed by the holy man. He ignored Rasputin’s predictions that war with Germany would drown Russia in her own blood. In November 1916 he replaced Shtiurmer as Prime Minister with Aleksandr Fedorovich Trepov (1862-1928) despite objections from Rasputin and the Empress. Whatever Rasputin’s actual power, the public perception that he ruled the country and lewd, unfounded rumours of his affair with Aleksandra, fatally undermined Nicholas’ autocratic authority.

Powerful Enemies↑

In June 1914 Rasputin survived a knife attack by a female disciple of his former ally Sergei Mikhailovich Trufanov (1880-1952), otherwise known as the monk Iliodor, a right-wing rabble-rouser who had begun to denounce Rasputin as a lecherous and traitorous devil. By early 1916 murder plots to rid the regime of Rasputin’s polluting presence were afoot within the police department and interior ministry. In the end it was the eccentric Prince Feliks Feliksovich Iusupov (1887-1967), the reactionary monarchist Duma member Vladimir Mitrofanovich Purishkevich (1870-1920) and the Tsar’s nephew, the Grand Duke Dmitrii Pavlovich (1891-1942), who successfully conspired to kill him. The lack of a formal investigation, precluded by the status of the murderers, fed speculation about the crime bordering on the fantastic and further assaulted the authority of the monarchy, which was swept away by popular revolt a few months later.

Assessments↑

Soviet interest in Rasputin was high but output usually restricted to reprints of primary sources, such as the memoirs of his enemies. Nostalgic post-Soviet texts tend to romanticise the holy man, while in the west popular biographies retell stories of mysticism, debauchery and intrigue, although some, like Brian Moynahan’s, offer a more nuanced portrait of an ambitious, perceptive, sympathetic and charismatic personality. Since 1980, however, some scholars have begun to unpick the Rasputin myth and examine what it tells us about the demise of imperial Russia. Mark Kulikowski has traced the crystallisation of the legend in newspaper accounts and popular pamphlets, while Orlando Figes and Boris Kolonitskii explore the role of smutty satire and rumours of treason circulating about the German-born Empress, the anti-war Rasputin and the German-sounding Boris Shtiurmer in de-sacralising the monarchy, weakening soldier discipline and unifying opposition forces. Rasputin’s relationship with the ruling family generated a scandal that shattered popular awe, legitimised revolution as patriotic and stirred up a violent outrage at charges of treason and corruption that would not just undo the Romanov dynasty but also haunt the Provisional Government which followed it.

Siobhan Peeling, University of Nottingham

Section Editors: Yulia Khmelevskaya; Katja Bruisch; Olga Nikonova; Oxana Sergeevna Nagornaja

Selected Bibliography

- Figes, Orlando / Kolonit͡skiĭ, Boris: Interpreting the Russian Revolution. The language and symbols of 1917, New Haven 1999: Yale University Press.

- Fuhrmann, Joseph T.: Rasputin. A life, New York 1990: Praeger.

- Fülöp-Miller, René: Der heilige Teufel. Rasputin und die Frauen, Leipzig 1927: Grethlein & Co.

- Kulikowski, Mark: Rethinking the origins of the Rasputin legend, in: Mendel, Arthur P. / Judge, Edward H. / Simms, James Young (eds.): Modernization and revolution. Dilemmas of progress in late Imperial Russia, Boulder, New York 1992: East European Monographs; Columbia University Press.

- Lieven, Dominic C. B.: Nicholas II. Twilight of the Empire, New York 1994: St. Martin's Press.

- Moynahan, Brian: Rasputin. The saint who sinned, New York 1997: Random House.