Introduction↑

The role and function of Australian propaganda on the home front during the war was largely unique, as it was produced in one of the few nations that maintained a voluntary system throughout the course of the conflict.[1] Despite two attempts to introduce conscription in the referenda of 1916 and 1917, Australia’s participation remained stubbornly voluntary. This had two major consequences for the use of propaganda, the first being that persuasion not compulsion was the sole means for the government to gain recruits – thus recruitment propaganda of an increasingly desperate nature was produced until the very close of the war. Secondly, the need for volunteer recruits also meant that any opposition to the war was regarded as highly threatening by the government and aggressive legislation under the auspices of the War Precautions Act of 1914 was strengthened during the conflict to suppress propaganda that could be regarded as prejudicial to recruiting.[2] Nonetheless, peace activists and members of the labour movement persisted in producing propaganda despite its illegality.

Another unique aspect of Australian propaganda was the vigorous (and sometimes virulent) conversation that emerged during the two failed conscription referenda of 1916 and 1917, in which government and community groups, for and against conscription, discussed the moral and economic issues raised by the war. Thus, while Australian government censorship was severe, propaganda was not simply dominated by pro-war government voices, as anti-war and anti-conscription protestors produced pamphlets in defiance of the law. As distinct as many of these debates were, Australian propaganda was nonetheless highly influenced by propaganda from Great Britain, which provided the template for recruiting posters as well as providing the fundamental just war defence for the conflict through the medium of atrocity propaganda. However, despite the importance of propaganda to the Australian war effort, there has been little work done on the topic to date.[3] This article will therefore canvas the topic as broadly as possible by focusing on five distinct aspects of Australian propaganda: the themes of official recruiting propaganda, the influence of Great Britain, the bureaucratic structure of official propaganda, unofficial propaganda (which was both pro-war and anti-war) and the conscription referenda of 1916 and 1917.

Themes of Recruiting Propaganda↑

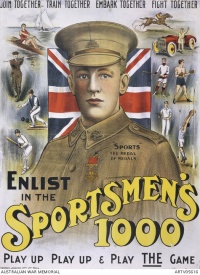

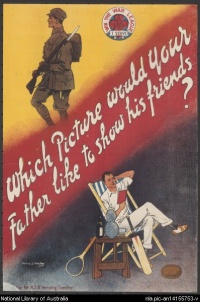

The themes of official Australian propaganda were widely varied, drawing upon international tropes while simultaneously developing nationalistic archetypes, the most notable being the muscular Australian “digger” soldier. Recruiting authorities also seized on Australian symbols of masculinity and sport – healthy bodied “shirkers” such as David Souter’s (1862-1935) iconic swimmer were depicted relaxing at the expense of their injured mates at the front. Shame was a primary function of these sorts of posters as a Queensland poster asserted:

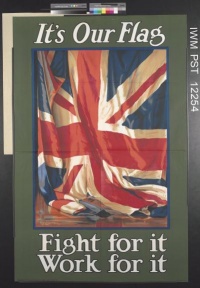

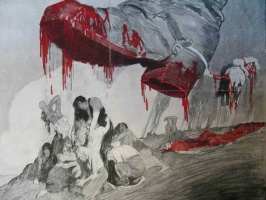

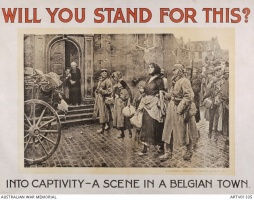

While a large amount of official propaganda appealed to imperial sentiment, the Union Jack and slogans about King and Country were produced alongside nationalistic propaganda as Australia began to position a distinct identity around its first defeat during the Gallipoli campaign.[5] Nationalist and imperialist themes were matched in volume with atrocity propaganda, which featured attacks on civilians by German soldiers. Atrocity propaganda closely followed British tropes, with Belgian women and children being threatened by the bestial “Hun.” From Zeppelin raids to the sinking of the Lusitania, atrocity propaganda was used by pro-conscriptionists and recruiters in Australia to promote the conflict as a just war. However, where pro-war propaganda promulgated the image of the German as a monstrous ogre, many labour newspapers targeted grotesquely overweight capitalists as the true enemy.

Influence of Great Britain↑

As a Dominion of the British Empire, Australia received assistance from Great Britain in its propaganda efforts. A significant amount of British propaganda entered Australia through both official and unofficial channels and was then either directly distributed or adapted for use in Australia. For example, the first recruiting poster apparently produced in Australia was based on a British design (a 1915 Australian film of the name Will they never come? was also inspired by the same British poster).[6] However, some British propaganda masqueraded as “unofficial” although it was in fact funded by the British government through the auspices of Wellington House, the propaganda organisation responsible for influencing overseas opinion and neutral countries.[7] For instance, in 1916, 25,000 copies of a book by Dutch cartoonist Louis Raemaekers (1869-1956), came into Australia through the stealthy subterfuge of a donation from the British publisher Hodder and Stoughton.[8] This was fairly typical of how Wellington House functioned as “none of the literature, except official publications, bore overt marks of its origin. It was placed on sale where possible or sent free and informally through individuals.”[9] The literature disseminated by Wellington House throughout the Empire had become so pervasive that in 1916 the Colonial Office forbade the distribution of British propaganda in the Dominions without the consent of the governments involved. The Colonial Office believed that loyalty was assured in much of the Empire, and declared that "propaganda in the Empire" was "except in a few special cases, a sheer waste of public money" and expressed a desire "to damp it down."[10]

Explicitly undermining the Colonial Offices’ ruling was the Reuters’ Supplementary Imperial Service, established in March 1917 and overseen by the Department of Information. Its purpose was to distribute overtly propaganda-inspired items designed to improve morale at home and to influence popular attitudes towards the enemy.[11] This too, was done by stealth, in that news stories fed to Reuters by the British government and then published in Australian papers were not overtly signed as having originated as official government propaganda. Indeed so covert were the changes that even the Australian manager of Reuters was not informed of the new system of propaganda distribution.[12]

On a more overt level, the Australian government also actively invited the British government to assist them with propaganda production. In June 1916, the British Parliamentary Committee responded to a request from the Australian Federal Parliamentary War Committee for help, saying they would be “happy to do anything...to assist the Australian Government in its splendid work” and sent a set of twenty-five posters and pamphlets.[13] The following year the Australian Minister for Defence, George Pearce (1870-1952), stated in a meeting that he would request that official British films be made available for viewing in Australia for recruiting purposes.[14]

Official Propaganda↑

In contrast to Great Britain’s sophisticated propaganda organisations, official propaganda in Australia was a decentralised ad-hoc affair for much of the war. Part of this was due to the fact that Australia had federated a mere thirteen years before the outbreak of the war and, as a consequence, the bulk of propaganda production for the first half of the war was controlled at the state level. However, there were occasions early in the war when federal authorities exercised direct control over propaganda production. For example, Pearce bypassed the states and commissioned the film Hero of the Dardanelles rather than doing it through recruiting bodies.[15]

For the majority of the war, official propaganda was subsidiary to the recruiting effort and was planned and produced through organisations such as State Recruiting Committees, semi-official groups such as the Win the War League, or State War Councils. It was not until the nearly close of the war that a specific Directorate of War Propaganda (October 1918) was founded which had clear propaganda objectives.[16] Before this, official propaganda underwent a slow evolution, centralising only as recruiting lurched from crisis to crisis as enlistment numbers waned and demand from Britain for Australian troops increased.

While propaganda production was very loosely federalised from mid-1915 under the auspices of the Federal Parliamentary War Committee and State Recruiting Committees were formed as part of the Commonwealth Voluntary Recruiting Scheme in early 1916,[17] the level of control exercised by the federal government was minimal until late 1916 when Donald Mackinnon (1859-1932) was appointed Director-General of Recruiting.[18] As Mackinnon recalled, the first failed conscription referendum of 1916 made it necessary “to have a more centralised organisation” because enlistments, previously “well maintained” had by December 1916 become “very light.”[19] By mid-1918, the government developed increasingly sophisticated techniques (a case in point being the “Recruitment Kit” described below) as numbers continued to decline.

There were numerous campaigns launched throughout Australia during the course of the war both at the state and federal level, the majority supported by an enormous volunteer effort. There were two significant federal campaigns which illustrate the evolution of official propaganda. The “Call to Arms” Campaign (December 1915) was launched largely in response to the results of the War Census Act, which had determined that there were 600,000 service-eligible men living in Australia.[20] The November 1915 decision to call for an additional 50,000 men on top of the regular quote of 9,500 a month came in response to Australia’s commitments in the Balkans and Gallipoli and the horrific casualty lists.[21] The grim news filtering in from overseas resulted in a hurried campaign that had a hectoring tone. The campaign was conducted with little persuasive rhetoric, visual or textual.[22] In essence, it consisted of a mailed out form and a few locally produced and distributed posters. The entire campaign was ill-conceived in that it coupled a bluntly composed form with more than a hint of compulsion from the local recruiting sergeants. First a form was sent out for eligible men to fill in. It read:

Those who refused to enlist and did not provide what were deemed adequate reasons, were paid a visit by the local recruiting sergeant and interrogated. As Joan Beaumont observed, the campaign was “counterproductive.”[24] This style of campaign was not repeated, particularly as its peremptory tone was even more inappropriate for the atmosphere of 1918. Following the defeat of two conscription referenda, the federal government recognised that a good propaganda campaign was the only hope they had to boost numbers – and because of that, it had to be more sophisticated and persuasive than any other propaganda campaign that had preceded it. Hence the introduction of the Recruiting Kit, which harnessed the talents of one of Australia’s top graphic artists, Norman Lindsay (1879-1969), and also used the skills of professional advertisers. The Recruiting Kit was painstakingly designed to promote the Voluntary Recruiting Ballot.[25] The idea was that eligible men would submit their names to a ballot, and should their name be drawn, they would agree to enlist.[26] Unlike the earlier “Call to Arms” campaign, the accompanying propaganda was diverse and plentiful, consisting of several posters, a film, mail-out pamphlets and newspaper advertisements. More importantly, it was bent upon persuading recruits to join, rather than compelling them through bureaucratic force. The new campaign refrained from calling the unenlisted man a shirker and instead sought to explain the Government’s perspective. J.R. Fletcher, a Melbourne businessman who was involved in the creation of the Recruiting Kit, argued that in the upcoming campaign of July 1918, “...it is necessary that they be educated in a courteous, yet forceful manner, in regard to their duties as citizens of the Commonwealth.”[27] The efficacy of the campaign will never be known, as it was launched a mere few weeks before the war ended.

Unofficial Propaganda↑

The extreme political viewpoints about the war – both for and against it – can be found in the unofficial propaganda. For example, it was not state propaganda which promoted aggressive anti-Germanism for much of the war, but instead the work of independent media. The most notable producers of atrocity propaganda were Sydney based magazine the Bulletin and newspaper owner Critchley Parker (1862-1944), who was essentially the Australian equivalent of the British media entrepreneur Horatio Bottomley (1860-1933), a media owner notorious for stirring up anti-German sentiment. One of Parker’s more memorable posters was titled “The Only Good German is a Dead German.”[28] He published numerous volumes, many originating in Great Britain, as well as atrocity propaganda pamphlets sourced from Russia.[29] Another group, called the All British Association, produced a newspaper which named and shamed members of the Western Australian community who were believed to be German.[30] In the case of the Bulletin, the focus was upon atrocities committed by Germans in Belgium, who assumed the role of the barbaric "other" over the course of the war.

In opposition to these pro-war views was the work of fringe anti-war groups and sections of the militant labour movement which produced (in the eyes of the authorities) the most seditious and contentious work. Through the use of the War Precautions Act, introduced in September 1914, an environment was created in which authorities could attempt to control any anti-war and labour movement propaganda that was deemed to be a threat to recruiting.[31] Despite this legislation and its enforcement, peace movements such as the Women’s Peace Alliance and the Australian Peace Alliance and industrial labour groups such as the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) continued to agitate against the war. Indeed, attempts to suppress propaganda were not always successful, with items such as the news article “The Lottery of Death” being republished in pamphlet form although it had been banned.[32]

The Conscription Referenda of 1916 and 1917↑

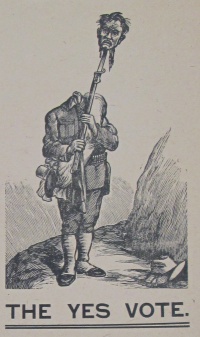

The two conscription referenda have become notorious in Australian historiography for dividing the nation. From the influence of the Easter Uprising on the Catholic vote, to the Labor party split, conscription left a lasting imprint.[33] However, the level of dispute in the community was also the sign of an actively engaged polity. As the propaganda from these campaigns demonstrates, responses to the issue of conscription were diverse. Diverse groups of people objected to conscription: from farmers in South Australia whose business would suffer should they be conscripted, to people who objected to conscription on religious grounds. Others who supported conscription were convinced the war desperately required more Australian troops and the only way to gain the number needed was through compulsion. Some members of the labour movement supported conscription as an extension of the concept of unionism as South Australian politician Thomas Ryan (1870-1943) wrote, “Is not this very compulsion the foundation upon which we have laid the superstructure of Labour?”[34] Alternatively, militant labour groups regarded conscription as a direct attack on unions. Many in the labour movement also argued that the loss of white labour to the war would result in an import of coloured labor, thus destroying the racial purity of Australia. One pamphlet read: “Maintain ‘White Australia’! This cannot be done if our manhood is deported!”[35]

Propaganda was the medium in which these conflicting viewpoints were deployed in the public realm. In effect, with what pieces of ephemera remain, or reports of ephemera that can be found in newspapers, a picture can be pieced together of Australians using the medium to repudiate opposing views and promote their own. Some forms of propaganda were perfect examples of rhetorical engagement: the Australian Women’s Peace Army and the Australian Freedom League, for example, produced lengthy pamphlets that explained their perspective in polite language.[36] Others, such as the sarcastically named “C.ENSOR” of Melbourne opted for shock tactics. In his “Conscription and Death” pamphlet, “Ensor” included an illustration of a soldier standing at ease with his own head impaled on the end of his bayonet.

Conclusion↑

While partly dependent on Great Britain for ideas and themes and lacking professional structure until nearly the close of the war, Australian government propaganda was nonetheless ubiquitous and at times compelling. Propaganda was not solely the domain of the government and was produced by many different sections of Australian society. It was created both by those who supported and opposed the war, by militant left wing organisations, women of the upper class, bureaucrats and former soldiers who passionately supported the war effort – to name a select few of Australian First World War propagandists. As often the only remaining source of information in libraries and archives about political groups or government campaigns, propaganda provides important historical insights into the many issues that faced the Australian polity during the war. This very brief overview of Australian propaganda will hopefully lead to more research and publications on this important topic.

Emily Robertson, University of New South Wales

Section Editor: Peter Stanley

Notes

- ↑ South Africa was the only other nation that did not introduce conscription.

- ↑ Beaumont, Joan: Broken Nation: Australians in the Great War, Crows Nest 2013, p. 45.

- ↑ Stanley, Peter: What did you do in the war, Daddy? A visual history of propaganda posters, Melbourne 1983. While Peter Stanley’s book did investigate First World War Australian propaganda, it had a much broader international focus. Any other mention of propaganda in Australian histories of the First World War have otherwise been fleeting.

- ↑ Pike, B.E.: To the men of Rockhampton and Central Queensland, hesitate no longer, Australian Commonwealth Military Forces, c.1915 – 1918. Collection of the Australian War Memorial [AWM], accession number ARTV00151. “Cooee” is a distinctly Australian term, being a call designed to travel long distances. During the war it was used in numerous recruiting campaigns. "On the days when the route marches were to arrive, there was special excitement, and coo-ees would echo among the City Buildings, to give an atmosphere of the outback in the heart of the metropolis." From: Catts, Dorothy M.: James Howard Catts M.H.R.: Ure Smith, Sydney 1953, pp. 55-56.

- ↑ Gorton, Stephen: War and Masculinity in Twentieth Century Australia. In: Journal of Australian Studies, 22/56 (1998), p. 86.

- ↑ Fine Recruiting Poster “Will They Never come”, In: The Argus, 5 July 1915, 10. To see the poster: ARTV07583, An appeal from the Dardanelles: will they never come?, Australian War Memorial [AWM]. Compare with the original poster: Will they Never Come, The Weekly Dispatch, London, 22 November 1914, collection of University of Minnesota Libraries. An Australian film was made of the same name, and also based on the British “Weekly Dispatch” poster and funded by the Ministry of Defence (see: To Aid Recruiting, in: The North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 21 April 1915, 2).

- ↑ Sanders, M.L.: Wellington House and British Propaganda during the First World War. In: The Historical Journal 18/1 (1975), pp. 119-146; Putnis, Peter / McCallum, Kerry: Reuters, Propaganda-inspired News, and the Australian Press During the First World War, in: Media History 19/3 (2013), pp. 284-304.

- ↑ CO 323/737 folio 54, 12 January 1916, Mr Gowers to Mr Macnaghten, Offices: Miscellaneous, The National Archives [TNA]; 001163/P10000 000501 Premier’s Office – Inwards Correspondence, 10 April 1916, Agent-General for Victoria, The Strand, to the Victorian Premier’s Office, Public Record Office Victoria [PROV].

- ↑ INF 4/1B, ‘The Activities of Wellington House During the Great War 1914-18’, p.1. TNA.

- ↑ CO 323/733, CO 323/733/2, Folio 29. Propaganda in the colonies: draft minutes of a conference held at Wellington House on 15 November 1916 with representatives of the Colonial Office; includes a draft printed circular for issue to colonial governments, 17 November 1916, forward draft minute, T.C. Macnaghton to Mr. Harris and Mr. Grindle of the Colonial Office, 18 November 1916, TNA.

- ↑ Putnis / McCallum, Reuters 2013, p. 284.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 291-292.

- ↑ A13886 FPWC.55, Assistant Secretary T. Trumble, Assistant Secretary, Department of Defence to Gavan Duffy, Secretary FPWC, June 1916, National Archives of Australia [NAA] Canberra.

- ↑ MP367/1 609/30/702; Director-General of Recruiting Central Correspondence, “Notes of Conference of Representatives of State Recruiting Committees held at Victoria Barracks,” 4 April 1917, p.3, NAA Melbourne.

- ↑ Hero of the Dardanelles. In: The Argus, 16 July 1915, p. 8.

- ↑ Announcement of Establishment of Commonwealth Directorate of Educational Propaganda on War and Peace Issues, 19 October 1918, A2481 A1918/6573, NAA Canberra.

- ↑ State Recruiting Committee of South Australia: Organising Secretary’s First Annual Report for the Year 1917, State Library of South Australia [SLSA].

- ↑ Robson, L.L.: The First A.I.F. A Study of its Recruitment 1914-1918, Melbourne 1982, p. 124.

- ↑ AWM 38 3DRL 6673/169 PART 1, Donald Mackinnon memo to historian 15 July 1919, p. 1, AWM.

- ↑ Scott, Ernest: Australia during the War. Sydney 1937, p.310.

- ↑ Minutes 24/11/1915, in FPWC. 2 Minutes of Meetings No. 2 [unsigned], NAA Canberra.

- ↑ “Australia has promised 50,000 more men, will you help us keep that promise?” Adelaide, S.A. Recruiting Committee, printed by Symo, c. 1915-1916; “N.S.W. Recruiting Campaign 50,000 men wanted,” Sydney, N.S.W. Recruiting Committee, printer unknown, c. 1915-1916.

- ↑ Scott, Australia 1937, p. 311.

- ↑ Beaumont, Broken 2013, p. 148.

- ↑ Robertson, Emily: Norman Lindsay and the ‘Asianisation’ of the German Soldier in Australia during the First World War, in: The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs 103/2 (2014), pp. 224-225.

- ↑ Donley, Graham: Voluntary Ballot Enlistment Scheme, 1918, in: Journal of the Australian War Memorial 30 (2003). Online: http://www.awm.gov.au/journal/j38/vebs.asp (Retrieved: 12 April 2014).

- ↑ Fletcher, J.R: Advertising Plan for Reinforcing A.I.F, Melbourne 1918, in: 204/346 World War 1914-1918 Australian Leaflets collection, AWM.

- ↑ The only good German is a dead German, calendar supplement to the Australian statesman and Mining Standard, 15 February 1917, collection of the AWM.

- ↑ German Barbarities in Russia, the evidence illustrated. Published by the authority of the Russian Government, Critchley Parker, Australia, 1915, collection of the National Library of Australia [NLA].

- ↑ Oliver, Bobbie: ‘All-British’ or ‘Anti-German’? A portrait of a Western Australian pressure group during World War I, in: Studies in Western Australian History 12 (1991), p. 28. Oliver writes: “No editions have been found of the All British newspaper which was published as a separate venture by some of the group.” Following the publication of Oliver’s work, some editions (only two) appear to have been found, and can be accessed on microfilm at the Battye Library, Western Australia.

- ↑ Beaumont, Broken 2013, p. 45.

- ↑ The Lottery of Death, People Printery, 1917, Riley Collection, NLA. Henry Earnest Boote, publisher and editor of the The Worker was prosecuted for publishing this article as it was deemed prejudicial to recruiting (see: Editor of ‘The Worker’ prosecuted, In: The Australian Worker, 30 November 1917, 6.)

- ↑ Beaumont, Broken 2013, pp. 378-85.

- ↑ Ryan, Thomas: National Preservation: a plea, Essendon, John Osborne Print, SLSA, p.11. Ryan broke with the Labor Party and joined Hughes’ Nationalist Party, gaining a seat in Victorian Parliament shortly before this pamphlet was produced. He only resigned his South Australian seat after he won his seat in Victoria.

- ↑ No Conscription Campaign: Wholesale Slaughter, Sydney, The Worker Printer, 1916-17, SLSA.

- ↑ Australian Women’s Peace Army: Special appeal by women to women: Manifesto, Melbourne, Fraser and Jenkinson, 1916-17, Riley Collection, NLA., pp. 1-2; Australian Freedom League: Lord Roberts on Conscience, Melbourne, Fraser and Jenkinson, 1916-17, Riley Collection, NLA, pp. 1-4.

Selected Bibliography

- Beaumont, Joan: Broken nation. Australians in the Great War, Crow's Nest 2013: Allen & Unwin.

- Damousi, Joy: Socialist women and gendered space. Anti-conscription and anti-war campaigns 1915-18, in: Damousi, Joy / Lake, Marilyn (eds.): Gender and war. Australians at war in the twentieth century, Cambridge; New York 1995: Cambridge University Press, pp. 254-273.

- Donley, Graham: Voluntary Ballot Enlistment Scheme, 1918, in: Journal of the Australian War Memorial 30, 2003.

- Fletcher, J. R.: Advertising plan for reinforcing A. I. F., Melbourne, in: Australian War Memorial (ed.): 204/346 World War 1914-1918 Australian leaflets collection, Melbourne 1918.

- Oliver, Bobbie: ‘All-British’ or ‘Anti-German’? A portrait of a Western Australian pressure group during World War I, in: Studies in Western Australian History/12 , 1991, pp. 28-39.

- Parker, Critchley: German barbarities in Russia. The evidence illustrated, Melbourne 1916: Critchley Parker.

- Putnis, Peter; McCallum, Kerry: Reuters, Propaganda-inspired news, and the Australian press during the First World War, in: Media History 19/3, 2013, pp. 284-204.

- Robertson, Emily: Norman Lindsay and the 'Asianisation' of the German soldier in Australia during the First World War, in: The Round Table 103/2, 2014, pp. 211-231.

- Robson, Leslie Lloyd: The first A.I.F. A study of its recruitment 1914-1918, Carlton 1970: Melbourne University Press.

- Ryan, Thomas: National preservation. A plea, Melbourne 1917: John Osborne Print.

- Sanders, M. L.: Wellington House and British propaganda during the First World War, in: The Historical Journal 18/1, 1975, pp. 119-146.

- Scott, Ernest: Australia during the war, Sydney 1936: Angus and Robertson Ltd.

- Stanley, Peter: What did you do in the war, Daddy? A visual history of propaganda posters, Melbourne; New York 1983: Oxford University Press.

- State Recruiting Committee of South Australia (ed.): Organising Secretary’s first annual report for the year 1917, 2 volumes, Adelaide 1918.