Introduction↑

Prior to the First World War, Australia, a self-governing dominion of white settlers within the British Empire, planned to aid Britain against Germany and to defend itself against Japan. To this end, Australia reformed its militia, founded a navy, effectively agreed to transfer its ships to Admiralty command in case of war, and joined New Zealand in discussions to raise a joint wartime expeditionary force for service within the British army. Historians have debated whether pre-war planning committed Australia in advance to Britain’s struggle with Germany. However, the fact that the most detailed preparations were actually made against a Japanese attack has been subject to minimal discussion.

Official historians of Australia’s experience of the First World War were relatively unconcerned with pre-war planning, which seemed to have little to do with raising the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) that became the dominion’s major wartime contribution to the British Empire’s struggle with Germany. The AIF was recruited and organised only after the war began, and this and other aspects of Australia’s engagement in the conflict seemed to overwhelm prior martial activity, in the words of Ernest Scott (1867-1939), “like a vast flood smashing through a dam.”[1] Arthur Jose (1863-1934) charted the pre-war birth of Australia’s navy and noted the “misgivings” and “recriminations” that met a British decision against creating a Pacific Fleet. However, signing over Australian ships to Britain’s Admiralty in August 1914 was, for Jose, a purely procedural matter and the real starting point for his narrative.[2] Charles Bean (1879-1968), who coordinated Australia’s official history and wrote half of it, saw pre-war planning as an informal and unfinished expression of a cultural impulse to respond as second-generation Britons to Germany’s challenge to the land that many still called the mother country.[3] No official historian recounted the preparations made against Japanese attack, which were rendered redundant by later events.

Apart from the creation of the navy, pre-war planning remained unstudied until the heightened nationalism of Australia’s 1970s and 1990s. Neville Meaney’s 1976 book The Search for Security in the Pacific argued that geographic isolation and the rise of Japan nudged Australia before 1914 toward different foreign and defence policies than those pursued in London. In 1992, John Mordike’s book An Army for a Nation portrayed pre-war military discussions about raising an Australian expeditionary force as a collusion between politicians and staff officers to commit thousands of unwary colonials to die in Britain’s defence. Mordike’s argument underpinned a prominent journalist’s 2011 critique of Australia’s contribution to NATO’s military occupation of Afghanistan, and also the 2014 book Hell-Bent: Australia’s Leap into the Great War by historian Douglas Newton. Ripostes to Mordike pointed to the absence of any commitment before the war to raising an expeditionary force or at any time to compelling men to join it, and also to the cultural impulse asserted by Charles Bean.[4]

Cultural and Political Context to Planning↑

During the 19th century, British settlers in Australia dispersed the continent’s indigenous inhabitants without mustering a militia or requiring significant aid from British troops. British naval mastery and Australia’s geographic isolation ensured that white settlement also went unchallenged by any foreign power. Never called on to provide recruits for the British army or navy, Australians were free to ignore military matters entirely, and many did. Others drew on England’s militia tradition to build, like their cousins in Canada and New Zealand, an inexpensive, undemanding and inward-looking military system based on part-time military service dedicated to the passive defence of borders in a military emergency. By the close of the century, practical support for imperial arms was limited to subsidising the few Royal Navy ships stationed in local waters and to offering and hastily raising small contingents of poorly-trained and badly-equipped volunteers for conflicts seen by Australians as emotionally or strategically significant, such as the Sudan War of 1885 and the South African War of 1899-1902.

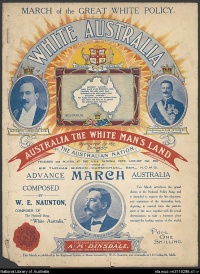

After the colonies united in 1901 to form the self-governing Commonwealth of Australia, the new federal government worked toward building a national militia and reducing military spending, though in 1902 it sent further contingents to South Africa. This gesture affirmed an Australian instinct for supporting British arms in a significant war. Also affirmed, however, was the right of Australian politicians, not British ones, to decide when and where Australian troops would be sent. Uncomfortably aware of the rise of rival armies and navies, Britain’s Admiralty and War Office looked to Australia and other British dominions to contribute to the Royal Navy, and even transform their militias into a reserve for the British army. But at a Colonial Conference held in London in 1902, Australia joined Canada in rejecting as inconsistent with self-government a modest request simply to allot a portion of troops in peacetime to overseas service in war. Culture and politics determined that Australia’s pre-war military planning would not allow an automatic reinforcement of Britain’s army and navy. In 1905 a strategic dilemma called into question for several years whether any reinforcement would come at all.

Strategic Dilemma↑

The victory in 1905 of an Asian power in the Russo-Japanese War coincided with the beginning of British concentration of naval and military resources for war in Europe. Japan was Britain’s ally but also, "so to speak, next door," wrote Alfred Deakin (1856-1919), the Liberal politician who would dominate Australian politics for the next five years, "while the Mother country is many streets away, and connected by long lines of communication."[5] If British ships evacuated the Pacific to assemble in the North Sea and Mediterranean, would Japan attack a defenceless Australia? The possibility seemed even greater if Australian troops left for a war in Europe. Some Australians worried that Britain would not so much be unable to protect Australia as unwilling. Australia’s open exclusion of Asian immigrants embarrassed the British government, and it seemed plausible, as Arthur Jose wrote to Deakin in 1908, that "the British navy may not be available to help us in a White Australia quarrel" with Japan.[6]

In 1905 the Australian National Defence League, a lobby group similar to Britain’s National Service League but supported by much of the political centre and left, called for militia service to be made compulsory. Two years later Alfred Deakin announced plans to raise a second militia of young men compiled to enlist in addition to the existing voluntary militia. Deakin also approved building small warships to secure Australian ports and coastal shipping lanes. Significant as they seemed and as expensive as they promised to be, these measures were no substitute for the possible loss of British protection. In 1908 Deakin bypassed imperial protocols to initiate an Australian stopover for a "great white fleet" of American warships cruising the globe to advertise Washington’s power, especially to Tokyo.

Yet Australians could not ignore the apparent German challenge to Britain. British defeat in a global war would damage Australia economically and perhaps politically. To the Bathurst Times the "truth of the matter" seemed to be "that Germany aims at occupying Great Britain’s present position" in the world "and, if she is successful, then God help Australia."[7] Middle-class Australians disrupted the official focus on anti-Japanese defence in 1909 when, in response to the Dreadnought crisis, they began to raise money for a battleship for the Royal Navy. They hoped to secure their own country and the mother country as well but, shackled culturally by their military system and economically by a small tax base due to a low population, they could not do both.

Britain eased pressure on Australia when, at a 1907 Imperial Conference, the new Liberal government of Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman (1836-1908) made no request that each of the dominions commit troops to a European war. Instead, dominion leaders were merely encouraged to bring their military training, weaponry and equipment into line with the British army. Dominion navies were not opposed for dividing naval spending and command, but instead were encouraged. Indeed, at a 1909 conference called in the wake of the Dreadnought crisis, Australia was urged to create an ocean-going squadron of a future Pacific Fleet that would include Canadian and British ships. Late that year Viscount Horatio Herbert Kitchener (1850-1916), Britain’s preeminent serving soldier, visited Australia to endorse local moves toward a single compulsory militia. Australia was being encouraged to build its own army and navy to protect its shores and sustain British power in the Pacific. “We manage the job in Europe,” Admiral Sir John Fisher (1841-1920) enthused of Australian and other naval contributions to a Pacific Fleet: “They’ll manage it against the Yankees, Japs, and Chinese.”[8] And if the Japanese alliance held, there would be trained troops for war against Germany. General Sir Ian Hamilton (1853-1947) urged in 1914:

At the 1911 Imperial Conference in London, British foreign minister Sir Edward Grey (1862-1933) assured dominion leaders of Japan’s good intentions, but warned that German control of the seas could entail the fall of England and the end of the empire. The message chilled George Pearce (1870-1952), defence minister in Australia’s new Labor government, who with his prime minister, Andrew Fisher (1862-1928), concluded that war with Germany was inevitable, even imminent.[10] The dominions stuck by their refusal to assign troops and ships to War Office and Admiralty use in peacetime, but Pearce made it clear that the transfer of ships and the despatch of voluntarily recruited troops would be almost certain in a German war. Like his dominion counterparts, Pearce agreed to begin mobilisation planning.[11] Back in Australia, Fisher warned the federal parliament "that the rights and liberties upheld by the British Government and British traditions are too sacred for us to allow the Old Land to be attacked with impunity."[12] The Sydney Morning Herald, Australia’s oldest broadsheet newspaper, carried a clear warning from Pearce to every Australian: "Our imperial responsibilities may require expeditionary forces, and we must be ready at any moment to get well forward into the firing line beyond the territorial limits of Australia."[13] There was no public questioning of this proposal to modernise the hitherto haphazard practice of raising wartime volunteer contingents.

Australia’s strategic dilemma appeared to have vanished. Australia would prepare for a war against Germany, and a Pacific fleet would keep Japan in check. Then came news that the fleet was to be aborted, apparently to allow further British naval concentration against Germany. First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill (1874-1965) said that Australia was protected by the Japanese alliance.[14] Australians were not reassured. "To offer us Japanese protection", Melbourne’s Punch magazine exclaimed in April 1914, "is very like telling Mary’s little lamb: 'Have no fear, small and tender sheep, you are excellently provided for. We have set the wolf to watch over you!'"[15] Calls for a second imperial naval conference were overtaken in August 1914 by the outbreak of war and Japan’s entry into the conflict as Britain’s ally. But the apparent return of Australia’s strategic dilemma ensured that war plans were more for regional defence than global imperial campaigns.

↑

Orders for British shipyards to build the first warships for an Australian navy briefly preceded the 1909 decision to create a squadron of a Pacific fleet. Liberal and Labor governments extended the building program and deflected calls to buy a Dreadnought for the Royal Navy. The Brisbane Courier echoed the official view that the squadron would provide "the best form of defence for Australia, and will also constitute a really effective part of Imperial naval defence whenever and wherever Imperial interests are assailed."[16] The Royal Australian Navy was proclaimed in 1911, around the time its centrepiece, an Indefatigable-class Dreadnought cruiser called Australia, was launched from a Scottish shipyard. Recruiting began in 1912, but almost 1,000 skilled and experienced sailors had to be borrowed from Britain, along with Vice Admiral Sir George Patey (1859-1935), appointed to command the new unit. When Australia, three second-class cruisers and three destroyers were ceremonially welcomed into Sydney in October 1913, Joseph Cook (1860-1947), the prime minister whose Liberal government succeeded Fisher’s Labor administration, warned "less advanced nations" to Australia’s north that a new navy had inherited "the unconquerable and indomitable spirit of our forefathers."[17] At the ambitious advice of another British admiral, Sir Reginald Henderson (1846-1932), the Fisher government agreed to a future building program that, had it not been interrupted by war, would have floated fifty-two warships. The fourteen ships and two submarines ready by August 1914 were already a respectable force south of the equator.

The abandonment of the Pacific fleet prompted urgent calls by two Australian naval officers for bases to secure the continent’s north. In Melbourne the Naval Board became factious and hysterical at the possibility of a Japanese invasion. The government bypassed its own naval chiefs to ask the Admiralty for a "definite" war plan for the service its ships might undertake if transferred to British command.[18] The Admiralty prioritised the securing of local waters and coastal trade but predicted, or simply hoped, that not all Australian vessels were needed for the job. Its May 1913 "war orders" proposed that Australia join the Royal Navy’s China squadron, reinforcing it against any challenger in the Pacific, including Japan, unless a sizeable German ship approached Australian waters. The three smaller cruisers could hunt for enemy vessels as far as German New Guinea or French New Caledonia, then patrol British sea routes in the Pacific and Indian Oceans.[19] Offering to secure both Australian and imperial interests, the plan was readily accepted by Australia’s government and Naval Board.

Military Planning 1911-1914↑

The decision to make militia service compulsory took effect in mid-1911, when male teenagers were obliged to begin cadet service. A year later, 17,000 cadets born in 1894 were inducted into the new militia, leavened for the moment by men who stayed on from the old voluntarily enlisted force. The militia slogged its way through the equivalent of sixteen days of simple drill performed at disparate moments over twelve months. Training in the second year, after the absorption of the 1895 cohort, was similarly sporadic and elementary. Absence from drill was common but short-lived and only rarely an expression of principled opposition to military service; late in 1912 the Melbourne Argus reported that only 384 militiamen refused to attend any drill at all.[20] A greater problem was a push by militiamen and also employers and parents for easier drill and discipline.

In July 1914, the induction of the 1896 cohort lifted the militia’s strength to 62,000 men. Two-thirds of the projected final number of infantry battalions were formed, half of the field artillery batteries, three-quarters of the cavalry regiments, and nearly all the engineer companies. Fourteen infantry and six cavalry brigades were more or less complete, and the way was clear to begin forming infantry divisions. The police reported that compulsory drill was spreading respect for authority among young men. Whether it was building an effective army was less clear, and a long-standing reliance on rifle club members as militia reservists remained. Ian Hamilton enthused about the cadets when visiting Australia early in 1914 as the British army’s Inspector General of Overseas Forces, but not about the militia, which he judged would need to outnumber an enemy by two to one to defeat it.[21]

Mobilisation planning agreed to at the 1911 Imperial Conference yielded defence schemes drafted by Australian staff officers. These were tutorials for political leaders and guides for visiting British generals as well as broad instructions for action in war. Such detail as they possessed related only to the possibility of a Japanese raid on Australia and the remote chance of a full-scale invasion. If war loomed, some militia units would reinforce professional gunners and engineers stationed at the forts protecting each capital city and also Thursday Island, a vital link between Australia and New Guinea. Meanwhile, rifle club members would guard remote points where overseas telegraph cables came ashore. If war began, the remainder of the militia would be called out and, after more rifle club members brought the ranks up to full strength, mobile columns would assemble to respond to any raids made on their nearest city. Repelling a serious invasion, though, would be the work of a small field army consisting of a cavalry brigade and infantry division made up of troops camped outside Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide. This little army must be capable, the 1913 defence scheme urged, "of acting as a mobile expeditionary force."[22] One reason for this stipulation was an inadequate railway network that had not yet linked the west and north of the continent with the populated southeast. The field army might have to be transported thousands of kilometres by sea merely to secure Australian soil. But the 1913 defence scheme also warned it was time "for giving wider effect to the policy of active offence."[23] In other words, expeditionary forces for imperial campaigning should be prepared.

Casual planning of such forces might have been common from the time the final Australian contingents were despatched to South Africa in 1902. The 1911 Imperial Conference failed to introduce urgency or a system to the process. Not until five months after the conference did Major General George Kirkpatrick (1866-1950), a Canadian acolyte of Kitchener’s appointed to steer Australia’s new militia through its early years, recommend to George Pearce that Australian troops occupy hostile bases across the southwest Pacific in war, presumably to forestall Japanese occupation as well as German.[24] A full year later, in November 1912, the chiefs of the Australian and New Zealand general staffs met in Melbourne. At their elbow was the Australian staff officer Major Cyril Brudenell White (1876-1940), recently returned from attachment to the Imperial General Staff in London. The chiefs agreed that the two dominions might together form either an infantry division or four cavalry brigades for an imperial campaign, but "to avoid delay and confusion when emergency arises" their governments must choose either to register volunteers from their militias for such a force or to form special units outside the militias.[25] Neither Pearce nor his Liberal successor, Edward Millen (1860-1923), would choose.

Brudenell White waited until May 1914 for a government decision on how an expeditionary force would be recruited and then, in the absence of one, sketched out how the force might be organised.[26] Unit organisation could not vary significantly from that of the British army, suggesting that White’s work would have focussed on logistics and recruiting quotas. Though the 1913 defence scheme suggested service in the Pacific, White probably saw the Mediterranean as the likely theatre of operations. Kirkpatrick corresponded unofficially on the matter with Sir Henry Wilson (1864-1922), the British army’s Director of Military Operations and chief planner for deploying a British Expeditionary Force to France, and the two concluded "that Egypt would be the most suitable."[27] Egypt would be the destination of the eventual AIF, the expeditionary force raised and recruited from volunteers after the war began.

Modification and Affirmation 1914↑

The war had not yet broken out when, on 3 August 1914, Joseph Cook’s cabinet offered Australia’s warships to the Admiralty and an expeditionary force to the War Office.[28] The offer did not prove that pre-war military planning had guaranteed an immediate surrender of Australia’s military resources to Britain. The politicians simply expressed at a heightened moment the cultural impulse to aid the mother country on the war’s front line. The offer also respected the right of Australians to volunteer for imperial service, while its practical expression ceded priority at first not merely to the securing of Australian territory but to its expansion by the conquest of German New Guinea.

Though the Royal Australian Navy in theory came under Admiralty direction on 8 August 1914,[29] the Australia did not join the China Squadron. With Germany’s East Asia Squadron possibly within striking range and Japan not yet an ally, Edward Millen and his naval advisers wanted their most formidable ship "nearer to [the] probable scene of action."[30] Over the next three months its guns reinforced a series of naval movements that reflected both Admiralty aims and Australian ambition, first scouting for German ships and then depositing small Australian and New Zealand landing parties to snap up Germany’s colonies south of the equator.[31] Only then did the Australian ships disperse to escort troop transports and reinforce the Royal Navy off of Europe.

Australia’s largest military effort in the war’s opening months, however, was the defence of local soil. A selective callout of the militia on 2 August 1914 was followed three days later by the first stage of full mobilisation,[32] during which 10,000 troops secured the major port cities and Thursday Island. One newspaper farewelled local militiamen "off to the front", another "the lads of the little army we have been apt to joke about" who "may yet have a chance of being 'tried out.'"[33] The chance never came. Japan joined the anti-German alliance on 23 August 1914, making redundant the plan to form a field army. Nonetheless the militia stood to arms until the end of the year, and until then outnumbered the AIF.[34]

That the AIF’s initial strength was set on 3 August 1914 at 20,000 men owed nothing to the pre-war military conversations with New Zealand, and perhaps nothing to Brudenell White’s plans. Possibly reflecting an impulse to proportionally match a reported Canadian offer of 30,000 troops,[35] it was immediately lifted anyway as thousands of volunteers came forward each week.[36] Nor did pre-war planning necessarily restrict the expeditionary force’s destination. The possibilities of deployment to South Africa and England were each projected before Egypt was confirmed.[37]

By 1916 the AIF was a small army numbering five infantry divisions and four cavalry brigades, exceeding Australia’s ability to reinforce it as casualties rose and the pool of recruitments began to dry up. Growing war weariness combined with an older, deeper commitment to voluntary participation in imperial conflicts to prompt the holding of two national plebiscites on conscription, first in October 1916 and then in December 1917 – and to defeat the proposal each time. The First World War changed much for Australians, but not their right to determine their own contribution to an imperial war.

Conclusion↑

Pre-war planning in Australia created a navy, expanded a militia, outlined a broad response to Japanese attack, assured London that ships and troops would almost certainly be offered for war against Germany, and sketched the organisation and likely destination of an expeditionary force. A tiny part of the pre-war arms race, Australia’s preparations before 1914 were peripheral, reactive and militarily insignificant. An inward-looking military tradition, a zealous commitment to self-government within the British Empire, and a deep fear of Japanese adventurism together ensured that planning did not quite commit the Australian government to raising an expeditionary force or to transferring its ships to Admiralty control. The government made these decisions only when war was certain, then deployed the militia to secure Australian soil and warships to guarantee the capture of German New Guinea. The AIF was recruited from volunteers who themselves decided whether or not to fight, and proposals for conscription were rejected. Charles Bean was right to see Australia’s pre-war planning as a minor and contingent expression of a collective impulse to defend the mother country, but Ian Hamilton was mistaken in predicting on the eve of war that Australia’s entire military force would simply be at Britain’s disposal.

Craig Wilcox, Independent Scholar

Section Editor: Peter Stanley

Notes

- ↑ Scott, Ernest: Australia during the War, Sydney 1936, p. 195.

- ↑ Jose, Arthur: The Royal Australian Navy, Sydney 1928, pp. xxxvi-xxxix, 6ff.

- ↑ Bean, C.E.W.: The Story of Anzac, volume 1, Sydney 1921, chapters 1-2.

- ↑ Wilcox, Craig: Relinquishing the Past. John Mordike’s An Army for a Nation, in: Australian Journal of Politics and History 40/1 (1994), pp. 52-65; Connor, John: Anzac and Empire. George Foster Pearce and the Foundations of Australian Defence, Melbourne 2011, chapter 2.

- ↑ Herald (Melbourne), 12 June 1905, p. 3.

- ↑ National Library of Australia, Alfred Deakin papers, MS1540/15/3621-2, Jose to Deakin, 13 January 1908.

- ↑ Bathurst Times, 14 September 1909, p. 2.

- ↑ Marder, A. J.: Fear God and Dread Nought. The Correspondence of Admiral of the Fleet Lord Fisher of Kilverstone, volume 2, London 1956, p. 266.

- ↑ Mordike, John: We Should Do This Thing Quietly. Japan and the Great Deception in Australian Defence Policy 1911-1914, Canberra 2002, p. 90.

- ↑ Pearce, George: Carpenter to Cabinet. Thirty-Seven Years of Parliament, London 1951, pp. 81f.

- ↑ Connor, Anzac and Empire 2011, pp. 32-35.

- ↑ Parliamentary Debates (Australia), volume 60, p. 131, 6 September 1911.

- ↑ Sydney Morning Herald, 5 July 1911, p. 15.

- ↑ Parliamentary Debates (United Kingdom), 5th series, volume 59, cols 1931-5, 17 March 1914.

- ↑ Punch (Melbourne), 2 April 1914, p. 547.

- ↑ Brisbane Courier, 19 August 1909, p. 4.

- ↑ Sydney Morning Herald, 6 October 1913, p. 7.

- ↑ National Archives of Australia, Navy Office Secret and Confidential Correspondence 1903-49, MP1049/1, 1914/0157, Fisher to Denman, 19 June 1912.

- ↑ National Archives of Australia, Navy Office Secret and Confidential Correspondence 1903-49, MP1049/1, 1914/0157, War Orders for H. M. Australian Naval Service and Admiralty Memorandums on War Orders for Ships Australia, Encounter, Melbourne and Sydney, 15 May 1913.

- ↑ Argus (Melbourne), 27 November 1912, p. 12.

- ↑ Parliamentary Papers (Australia), 1914, volume 2, no. 14, Report on Australian Military Forces, 24 April 1914, p. 45.

- ↑ National Archives of Australia, Defence Schemes 1906-38, MP826/1, 3B, General Scheme of Defence [1913], p. 5.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ National Archives of Australia, Department of Defence Correspondence 1906-13, MP84/1, 1802/2/152, Kirkpatrick to Pearce, 30 November 1911.

- ↑ National Archives of Australia, Department of Defence Correspondence 1906-13, MP84/1, 1856/1/33, Summary of Proceedings of Conference between Major General Godley and Brigadier General Gordon, 20 November 1912.

- ↑ National Archives of Australia, Department of Defence Correspondence 1907-17, A2023, A146/2/1, White to Adjutant General, 22 May 1914.

- ↑ State Library of New South Wales, G. M. Kirkpatrick Memoir 1909-14, ML MSS 5708, p. 309.

- ↑ Parliamentary Papers (Australia), 1914-17, volume 5, paper no. 10, Correspondence Regarding the Naval and Military Assistance Afforded to His Majesty’s Government by His Majesty’s Oversea[s] Dominions, 11 November 1914, p. 1434.

- ↑ National Archives of Australia, Navy Office Secret and Confidential Correspondence 1911-22, MP1049/1, 1914/0299, undated typed notes ‘Transfer of HMA Fleet to Admiralty, August 1914.’

- ↑ National Archives of Australia, Navy Office Secret and Confidential Correspondence 1911-22, MP1049/1, 1914/0299, Macandie to Navy Office, 31 July 1914.

- ↑ Connor, John: The Capture of German New Guinea, in: Stockings, Craig/Connor, John (eds.): Before the Anzac Dawn. A Military History of Australia to 1915, Sydney 2013, pp. 283-96.

- ↑ Commonwealth of Australia Gazette, 50/1914, 3 August 1914, p. 1235, and 52/1914, 6 August 1914, p. 1343.

- ↑ Geelong Advertiser, 8 August 1914, p. 4; North Queensland Register, 10 August 1914, p. 4.

- ↑ Wilcox, Craig: Defending Australia 1914-1918, in: Dennis, Peter/Grey, Jeffrey (eds.): 1918, Defining Victory, Canberra 1999, pp. 174-78; National Archives of Australia, Department of Defence AIF Correspondence 1914-17, B539, AIF112/2/218, Chief of the General Staff’s statement for the Minister of Defence, 24 November 1914.

- ↑ Newton, Douglas: Hell-Bent. Australia’s Leap into the Great War, Melbourne 2014, p. 167.

- ↑ Beaumont, Joan (ed.) with Vijaya Joshi: Australian Defence. Sources and Statistics, Melbourne 2001, p. 108.

- ↑ Bean, Story of Anzac 1921, pp. 97f; Grey, Jeffrey: The War with the Ottoman Empire, Melbourne 2015, p. 26.

Selected Bibliography

- Connor, John: Anzac and empire. George Foster Pearce and the foundations of Australian defence, Cambridge; New York 2011: Cambridge University Press.

- Greenwood, Gordon / Grimshaw, Charles (eds.): Documents on Australian international affairs 1901-1918, Melbourne 1977: Thomas Nelson.

- Lambert, Nicholas: Economy or empire? The fleet unit concept and the quest for collective security in the pacific 1909-14, in: Kennedy, Greg / Neilson, Keith (eds.): Far-flung lines. Essays on imperial defence in honour of Donald Mackenzie Schurman, London; Portland 1997: Frank Cass, pp. 44-83.

- Meaney, Neville: A history of Australian defence and foreign policy 1901-23. The search for security in the Pacific, 1901-14, volume 1, Sydney 1976: Sydney University Press.

- Mordike, John: An army for a nation. A history of Australian military developments, 1880-1914, Sydney 1992: Allen & Unwin.

- Moses, John A. / Pugsley, Christopher (eds.): The German empire and Britain's Pacific dominions, 1871-1919. Essays on the role of Australia and New Zealand in world politics in the age of imperialism, Claremont 2000: Regina Books.

- Newton, Douglas J.: Hell-bent. Australia's leap into the Great War, Melbourne 2014: Scribe.

- Pearce, George Foster: Carpenter to Cabinet. Thirty-seven years of Parliament, London; New York 1951: Hutchinson.

- Stevens, David / Reeve, John (eds.): The navy and the nation. The influence of the navy on modern Australia, Crows Nest 2005: Allen & Unwin.

- Ward, Stuart: Security. Defending Australia’s empire, in: Schreuder, D. M. / Ward, Stuart (eds.): Australia's empire, Oxford; New York 2008: Oxford University Press, pp. 232-258.

- Wilcox, Craig: Relinquishing the past, in: Australian Journal of Politics & History 40/1, 2008, pp. 52-65.

- Wilcox, Craig: Edwardian transformation, in: Stockings, Craig / Connor, John (eds.): Before the Anzac dawn. A military history of Australia before 1915, Sydney 2013: NewSouth Publishing, pp. 255-282.