Introduction↑

Military operations have always required considerable prior preparation. Assembling, clothing, training, feeding, equipping, and transporting a large fighting force, potentially across an extended period, cannot simply be improvised. Thus, over time, as armies and navies have expanded in scope and scale, so the logistical, cartographic, and other vital ancillary services that facilitate their operations have developed accordingly, becoming increasingly sophisticated in response to the expanding needs of the states that maintain them. The Royal Navy of the eighteenth century is a prime example: it only functioned as a military machine able to project power across the globe because it controlled a huge industrial hinterland that built, maintained, and readied ships for dispatch as its admirals commanded. Nevertheless, if the existence of a comprehensive support infrastructure is hardly new to armed forces, the nineteenth century saw a major enhancement and professionalization of one particular facet of military preparation: higher staff work. Increasingly, major institutional structures were set up and developed to think about the nature of warfare; to ascertain, measure, and assess the strength, intentions, and capabilities of potential enemies; and to consider in advance the campaigns that would be undertaken should conflicts arise with one or more of these possible opponents. In many respects, the Prussian Great General Staff under the inspired leadership of Helmut von Moltke the elder (1800-1891) led the way in this area, ultimately becoming the model that others followed.

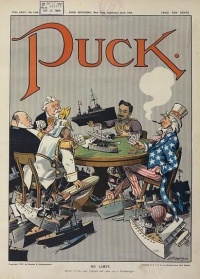

The success that Prussian arms achieved in the German Wars of Unification through seemingly meticulous and detailed planning not only greatly enhanced the Great General Staff’s reputation domestically, it also ensured the widespread adoption in the military establishments of other countries of the Prussian approach to military planning. Thus, in the decades prior to the outbreak of the First World War all the European great powers thought not only about the possibility of a major war on the continent, but also about the manner in which they would choose to conduct this war should it erupt. The plans they developed varied from state to state, changed over time, and in many cases have been subject to considerable dispute among historians. This is particularly true for Germany and Great Britain, though more recently the war planning of the other great powers has attracted the attention of international scholars. This article will focus on German and British planning, before highlighting some distinctive features of some of the other great powers’ military and naval planning as it pertains to decisions made in London and Berlin.

German War Planning↑

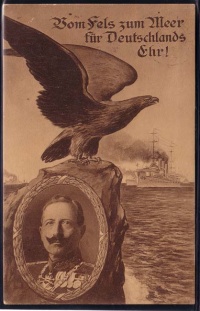

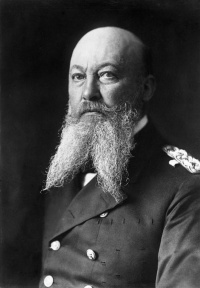

The armed forces of the German Empire consisted of both an army and a navy. As the Reich was a continental land power, the army was the more vital of the two for maintaining national security. It also loomed larger in the national consciousness, having a pedigree that went back to the Great Elector in the seventeenth century. However, under Kaiser Wilhelm II (1859-1941), who had been obsessed since he was a child with the prestige that attached to his grandmother, Queen Victoria (1819-1901), as a result of the Royal Navy’s preeminent global reach, a great deal of time, money and effort was spent building the German Navy from a small coastal defence force of no great international significance into the second most potent instrument of sea power in the world. Not surprisingly, given the huge and detrimental impact this decision had on both German foreign and domestic policy, a great deal of historical attention has focused on the origins and underlying purpose of the so-called ‘Tirpitz plan’, the scheme put forward by Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz (1849-1930), State Secretary at the Imperial Navy Office (Reichsmarineamt), that led to the massive expansion of the German Navy.[1] By contrast, there has been much less scrutiny of the naval hierarchy’s intended use of the force that they were creating. There are two main reasons for this.

The first is a bureaucratic one. The organizational structure of the German navy placed responsibility for the construction of the fleet with one agency, the Imperial Navy Office, and for the planning work for the use of the fleet with another, the Admiralty Staff (Admiralstab). Of the two, the former definitely had the higher profile. Not only was the man in charge, Alfred von Tirpitz, the most prominent naval officer of his day and a magnet for contemporary and subsequent attention, but, in addition, its mission to transform the German navy was a much more visible and dramatic activity than the more mundane role of producing dusty annual planning documents, most of which were never implemented.

Compounding this, the German navy’s massive expansion under Tirpitz was justified with reference to a particular strategic concept, namely Tirpitz’s ‘risk theory.’ The rationale behind this doctrine was that by building a powerful navy, the Reich would create a situation where rather than ‘risk’ taking losses in a war with Germany that would render the Royal Navy weaker than the navies of France and Russia – hence the name ‘risk theory’ – Britain would come to terms with Germany and acquiesce, however reluctantly, it in its efforts to become a world power. In effect, therefore, the German navy was not built to fight in war, but to act as a diplomatic lever for extracting concessions in peacetime. Indeed, if the risk theory actually worked, there would be no war between Britain and Germany, rendering planning for such an occurrence nugatory. As it happened, not only did the risk theory not work, but, in addition, the German navy never actually reached the size and power that was felt was necessary to enable it to meet the Royal Navy in battle. This double circumstance rendered war planning a largely abstract, even unreal, activity for most of those undertaking it.

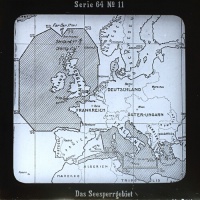

Nevertheless, if with only a few exceptions historians have largely ignored it, war planning for the German navy did take place.[2] For all likely scenarios, except a conflict with Britain, Germany was in a strong position. Its naval forces were considerably stronger than those of major European rivals such as France and Russia, which meant that a successful attack by either of these nations’ maritime forces was unlikely. War against Britain, however, posed significantly greater challenges. The German High Seas Fleet was certainly strong enough to control the Baltic – thus securing imports from Scandinavia while simultaneously blocking a crucial seaborne route to Russia – and also to ensure that the German North Sea coast could not be threatened. Yet, unless the odds were significantly improved in its favour, there was little else that it could hope to achieve. Accordingly, whittling away the strength of the Royal Navy until the two forces were more closely matched became the main German goal. There were two ways in which it was believed this might be achieved. The first was through economic warfare. Owing to the emphasis that Tirpitz placed in his ‘risk theory’ on the role of battleships and decisive fleet encounters it is often assumed that neither he nor the rest of the German naval leadership was interested in pursuing a guerre de course. This is, in fact, a misreading. While Tirpitz did believe that the battle fleet was the preeminent instrument of naval power, he also saw the world in neo-mercantilist terms and, as a result of this, he believed that British foreign policy was determined by the needs of the financiers of the City of London. As they were susceptible to economic pressure, it was vital, if Germany was to hold any leverage over Britain, that the German navy pose a credible threat to British commerce. Accordingly, Tirpitz almost single-handedly ensured that when the international laws of war at sea were codified – as for example at the London Naval Conference (1909) – the German delegates were instructed to oppose any measure that would grant immunity from capture to private property at sea. For, although this would protect cargos headed to German ports – the main concern of almost everyone else in the German government – it would also limit the right of German commerce raiders to hunt down British merchant vessels, a right which Tirpitz saw as vital.[3] Having once secured this decision, Germany’s naval planners integrated economic warfare into their plans for war. It was hoped that by conducting a campaign against British merchant shipping in distant waters, the Royal Navy would be forced to dispatch warships away from home to defend it. As the German navy maintained relatively few warships on foreign stations, the Admiralstab planned to convert vessels from Germany’s civilian shipping lines into auxiliary cruisers at the outset of conflict. It was expected that these impromptu raiders would create sufficient panic on the shipping lanes that the authorities in London would be compelled to divert resources to counter them.[4] Second, the German naval planners worked on the assumption that the Royal Navy would adopt that service’s traditional wartime policy of sealing up the coasts of its enemies and mount a close blockade of Germany’s North Sea littoral. As the German coast was very strongly protected, it was expected that the Royal Navy would suffer considerable losses from such an approach. This combination of distraction, diversion, and attrition would, it was assumed, even the odds sufficiently for the German fleet to be able to meet the Royal Navy with some prospect of success.

There were, however, major flaws in these plans. For one, Britain’s Naval Intelligence Department (NID) had little difficulty gauging German intentions. A range of counter measures against German commerce raiders was introduced to ensure that a dispersal of force would not be necessary on anything like the scale the Germans had hoped. Equally, in 1912 the British naval leadership decided that an observational blockade against the German coast was no longer possible. Accordingly, they pulled back their forces and prepared for what became known as a ‘distant blockade’, a move to which the Admiralstab had no answer.[5] The result was that when conflict came, the German navy was not in a position to realise its objective of wearing down its opponent until a battle was possible on equal terms. Consequently, for the most part its ships stayed in port.

While little scrutiny has been brought to bear on the German navy’s war planning, a great deal of attention has focused on the schemes devised by the Prussian Great General Staff. In the six decades following the end of the First World War, a common narrative developed to explain the plans they drew up.[6] The German Empire, it was pointed out, was a large urbanized industrial country in the heart of Europe. This had two consequences. First, Germany was surrounded by other great powers. While an alliance with Austria-Hungary removed the danger from the south, long-term political differences meant that Germany always had to reckon with the possibility of an attack from the west by France or from the East by Russia. In a worst-case scenario, conflict with both simultaneously could be expected. For Germany, this meant that military planning had to take into account the prospect of a war on two fronts against states with sizeable populations, plentiful resources, and well-developed military machines. Second, the fact that the German economy was heavily industrialized made it highly dependent upon access to global markets. Many of the raw materials – for example, oil, rubber, and metal ores – necessary to sustain German manufacturing and thus the livelihood of the German populace came from overseas. Similarly, notwithstanding considerable support being accorded to German farming, the nation was not self-sufficient in foodstuffs. Accordingly, without a regular and dependable inflow of these vital goods, industrial production, including of essential war materials, would be disrupted and food, the foremost of the necessities of life, would be in reduced supply. The problem was that of all the predictable consequences of great power conflict, one of the most certain was that it would be highly disruptive to the economy. Not only would millions of workers be called to the colours, thereby removing them from their normal industrial and agricultural pursuits, but in addition the normal flow of international cross-border trade would be suddenly thrown into turmoil, creating additional shortages across the land. The implications of this for the ability to sustain a major conflict were considerable. Indeed, there were some, of whom the elder Moltke is the best known, who believed that Germany was no longer capable of fighting, let alone winning, a drawn-out war against great powers.

For many historians, these factors were crucial: German war planning did not merely take into account the country’s challenging geographical position and its vulnerability to any denial of access to global markets and the strategic raw materials that were supplied from them, it was dominated by these considerations. In the traditional historiography the twin problems of a two-front war and the avoidance of economic dislocation were addressed simultaneously through one comprehensive solution, the infamous ‘Schlieffen Plan’. According to this narrative, when Alfred von Schlieffen (1833-1913) became Chief of the Great General Staff in 1891, he immediately embarked upon a reconsideration of German war plans designed to nullify both issues. His intention was to bring about a war of such limited duration that the commercial disruption it would cause would not have time adversely to affect Germany’s war effort. To achieve this, he proposed to deal with the problem of a war on two fronts by defeating Germany’s enemies sequentially. On mobilisation, overwhelming force would be deployed first against one opponent, whose armies would be swiftly destroyed in a concerted campaign of annihilation. That having been achieved, Germany’s armies would then take advantage of the nation’s short interior lines and excellent rail network to re-deploy against the remaining opponent, who could be mastered in leisurely fashion. The practical question was how to achieve this.

According to the traditional analysis, Schlieffen experimented with various different permutations during the decade and a half of his tenure of office, but in the end he was inexorably drawn to the conclusion that the best way of securing his aims was to commence any continental war with an all-out attack on France mounted through Belgium and Holland. The reasoning behind this was clear. Russia, in Schlieffen’s estimate, could not be defeated rapidly, as the vast territorial expanse of the nation provided limitless opportunities for a prolonged strategic withdrawal. France, by contrast, was not endowed with such endless space. This did not mean that an attack on France would be easy. Schlieffen concluded that France could not realistically be assaulted across the short, mountainous and heavily fortified Franco-German border given the splendid opportunities this terrain provided for a stubborn and protracted defence. However, an offensive via the flat and largely unfortified plains of Belgium offered much more scope. German armies advancing there could avoid French fortresses and could attack the French lines from their exposed northern flanks. If done rapidly and with precision, this would allow for the swift encirclement of the French armies and their prompt destruction in a classic battle of annihilation. The victorious German armies could then re-train and turn east.

The traditional analysis of German planning, with its emphasis on the inexorable linear development from 1891 to 1905 of a scheme for an opening offensive against France, held sway in the historiography for a very long time. For the most part this was because such documentation as still existed seemed to support it unambiguously. Admittedly, the surviving sources were few. On 14 April 1945 allied bombers had attacked Potsdam, where the German military archive was located, and the result had been the complete obliteration, or so it was thought, of all the General Staff files for the period leading up to the First World War. Such wide-scale destruction left little for historians to go on, but among the papers that did survive, because they were held elsewhere, was Schlieffen’s Denkschrift or great memorandum dated December 1905 (but probably finished and handed to his successor in January 1906) in which he articulated what was presumed to be the culmination of an entire career’s thinking on how best to mount an attack on France. For the German military historian Gerhard Ritter (1888-1967), as for others, here, in this exemplary source, was the blueprint for the operation that was mounted in August 1914: an attempt to outflank France by marching through Belgium and thereby bring about a swift victory that would obviate the problem of economic dislocation from a long war and solve the problem of a war on two fronts.

However, what had once seemed like an unchallengeable interpretation based upon a small but unimpeachable body of primary materials came under considerable scrutiny in the 1990s. The catalyst for this was an unexpected but considerable augmentation of the available evidential base. With the ending of the Cold War it was discovered that the German military files in the Reichsarchiv that had been destroyed in April 1945, while certainly the main documentary collection on German war planning, were not the only source on this topic ever to have existed. Copies of many important papers had also been held by the office charged with writing staff histories of German operations for use by the German high command; and these records had survived the war, being captured in 1945 by the Red Army. Their availability following the collapse of the Soviet Union meant that planning documents that had been destroyed decades previously could now be read if not in the original then at least as verbatim duplicates. This opened up whole new vistas for research and scholarship, which led two areas in particular to come under sustained criticism.

The first of these was the idea that the German military leadership thought that it would be possible to fight a short war. As we have seen, one of the rationales frequently attributed to Schlieffen’s proposed outflanking offensive against France was that it would lead to a rapid victory. There had long been doubts among historians as to how widely shared this view actually was. One of the prime causes of this doubt was a modification introduced into the plan by Schlieffen’s successor as Chief of the General Staff, Helmuth von Moltke the younger (1848-1916). Whereas Schlieffen had proposed to march German armies through both Belgium and the adjacent Maastricht region of the Netherlands, it had long been known that Moltke restricted the German advance to Belgium only. His rationale for doing so was that this would keep Holland out of the war: the advantage being that if the Netherlands were a neutral power, Dutch ports would be a route for overseas goods to evade a blockade and reach Germany. Such a ‘windpipe’, as Moltke called it, would not be necessary in a short war. Only in a long conflict, where economic disruption could be damaging, would it have any purpose. This inevitably raised the suspicion that Moltke was uncertain about the viability of the short war plan. However, in the absence of other evidence, a suspicion was all it was.

The newly released planning documents transformed this into a certainty. Research undertaken by Stig Förster showed not only that the younger Moltke expected a future war to be a long one, but that almost every other member of the German military hierarchy, with the exception of Schlieffen himself, shared this view.[7] This, of course, begged the question, if Moltke did not adhere to Schlieffen’s assumption that a short war was possible, why did he retain a plan designed to secure one? One plausible answer was that it was the best plan available. Moltke might have doubted that a quick victory was attainable, but there was always a chance that Schlieffen was right and that it would succeed. Moreover, even if it was tried and failed, it still had considerable merits. After all, an advance through Belgium and northern France would secure control of two of the most heavily industrialized and mineral rich regions of Western Europe. What better way to begin a long war that to deprive your opponents of key economic assets and secure them for yourself instead?

The second criticism deriving from the new sources was the idea of the inexorable linear development of German war planning under Schlieffen. Traditionally, it was argued that when Schlieffen took over in 1891, he reoriented Germany’s war plans away from an attack on Russia, the option preferred by his predecessors, towards an initial offensive against France and that, in so doing, he progressively moved his central operational idea to an ever wider outflanking manoeuvre. This culminated in the Denkschrift of December 1905 in which a decade and a half’s thinking was crystalized in perfect form. However, the documents recovered from the Soviet Union made this progressive, step-by-step journey look anything but inevitable or linear. On the contrary, historians such as Terence Holmes and Robert Foley argued that they showed that Schlieffen was both more operationally flexible than previous studies had made out – he certainly was not wedded exclusively to campaigns of encirclement – and tested a great many more ideas in his manoeuvres and war games than had previously been credited.[8] That he ended his professional life proposing an all-out offensive against France by means of a gigantic campaign of encirclement was less a matter of strategic dogma than altered circumstances. After all, the December 1905 Memorandum was written after the breakdown of Russian military power following the defeat in the Russo-Japanese War. That the best units of the Russian army would be degraded on the battlefield in circumstances that weakened the authority of the Romanov regime and forced the remaining elements of the military into several years of morale-sapping operations to restore domestic order was clearly not something that Schlieffen could have foreseen in the 1890s; but he definitely could take advantage of it once it happened. Throwing the entire German army at France without regard to Russia was possible only in the aftermath of this Tsarist debacle and Schlieffen swiftly opted to capitalize on this unexpected possibility. As such the December 1905 Denkschrift was not so much the culmination of years of thinking and development, as a serendipitous opportunity gratefully seized. Of course, this did not mean that there was no link between Schlieffen’s prior military thinking and the strategy espoused in late 1905. Clearly, Schlieffen did not write this document in a vacuum, but was informed by his past knowledge and experience. However, notwithstanding such continuities, the development of his infamous plan was evidently much more complex and contingent than traditional interpretations would have had it.

And that presupposes that a Schlieffen Plan existed at all. While most historians saw the new documents as proof of the complex nature of Schlieffen’s strategic thinking, one historian, Terence Zuber, drew more controversial conclusions. As far as he was concerned, there was nothing either in the views that Schlieffen articulated prior to 1905 or in the manoeuvres and war games that he orchestrated as Chief of the General Staff that offered any prior indication that he wanted to launch a great campaign of encirclement against France. This led him to view the 1905 Denkschrift in a different light. For Zuber, this was not a war plan at all, but a bureaucratic manoeuvre for extracting additional resources from a reluctant Ministry of War. The evidence lay in the manpower deployed in the 1905 document. It called for an army of 96 divisions in the west, 82 of which would be deployed on the right wing. However, at that time, a total of only 72 were available, meaning that 24 divisions required to make the plan work did not actually exist. While some historians have concluded that Schlieffen would have formed these extra units out of the surplus men called to the colours on mobilization, Zuber argued that no serious military planner would devise a scheme requiring assets that were fictitious and which would need to be improvised in a hurry should war come. Thus, if Schlieffen produced a document requiring more resources than actually existed, it could only be as a stratagem for highlighting the need for an expanded force structure and compelling the Ministry of War to provide it. As such, the 1905 Denkschrift was clear evidence of internal bureaucratic manoeuvring; it was not a real war plan. Indeed, Zuber provocatively concluded in his initial ground-breaking article that ‘there never was a “Schlieffen Plan”.’[9]

Zuber’s scholarship was pioneering and original, but his major conclusions have not found widespread acceptance.[10] However, whether one agrees with him or not, his work underlines a point that does command consensus, namely that Schlieffen’s thinking and hence German military planning was much more complex and varied than was once thought: there was no straight line leading from the war plans of 1891 to the operations of 1914. It is also now generally accepted that there was no ‘short war illusion’ among German military leaders. The army hierarchy certainly desired a quick victory and they adopted a plan that might perhaps deliver one, but they did not expect it. Thus, when war came, the German military campaign plan – now really ‘the Schlieffen-Moltke Plan’ rather than merely the ‘Schlieffen Plan’ – involved many elements predicated on a prolonged conflict. The most notable of these were: excluding southern Holland from the path of the German offensive thrust; protecting Alsace and more especially the Lorraine iron ore fields from French re-conquest; and placing an army corps in East Prussia to stem the anticipated Russian advance. The danger of such changes was that they made a short war even harder to deliver. However, if a quick victory was considered unlikely, as the scholarly consensus now suggests, they represented a sensible insurance against the difficulties of a protracted struggle.

British War Planning↑

At the end of the nineteenth century, Britain’s main rivals were France and Russia. Anglo-French competition existed across the colonial world but was particularly pressing in the Nile valley. Here things came to a head in 1898 with the Fashoda crisis, a spat between two armed expeditions that looked at one stage as if it would lead directly to war. At the same time, the ‘Great Game’ in Asia kept Anglo-Russian tensions permanently high in Persia, Afghanistan, and the Indian borderlands. In the face of these circumstances, the parameters of British war planning seemed relatively clear. To ensure that the forces in India were able to resist a Russian assault, a major segment of the British Army was designated as reinforcement for the North-West Frontier. In time of war, it would be shipped from Britain to India to forestall any Russian attack; other portions of the army, acting in conjunction with the navy, were reserved for amphibious assault against French overseas territories; the remainder would defend the home islands. Meanwhile, the two largest British naval forces, the Mediterranean Fleet and the Channel Squadron, would combine to ensure that the French navy, the bulk of which was stationed in the Mediterranean port of Toulon, was either bottled up there or, should it sortie, was met and destroyed in battle. Likewise, should any Russian units in the Black Sea exit into the Mediterranean, they, too, were to be eliminated. The containment or destruction of all hostile assets in the Mediterranean would not only give Britain command of these important waters, it would also ensure that there were no naval forces powerful enough to escort an invading army across the English Channel. The protection of the British Isles would, therefore, be ensured at the same time.[11]

So long as France and Russia remained the main threat, this division of forces and apportionment of responsibility endured. However, at the start of the twentieth century the certainties of the previous era began to change. French leaders, shocked by the prospect of war with Britain, which had loomed large at Fashoda, reassessed their priorities and decided that security against Germany rather than colonial one-upmanship with Britain was the top concern. This made an accommodation with London desirable and French policy adjusted accordingly. As a reduction in Anglo-French hostility was equally attractive in Whitehall, the circumstances were propitious for a thaw. The Entente Cordiale, the bedrock of future Anglo-French friendship, was the result. The Russian threat diminished for different reasons. Russia’s quest for influence in Korea and Manchuria turned the attention of St Petersburg away from Britain towards Japan. When the friction between the two came to a head in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5, the Tsarist forces were so soundly beaten that the Tsar’s army was thrown into turmoil and the Russian navy almost ceased to exist. Thus, in the opening years of the twentieth century, the countries against which British defensive arrangements had for so long been arrayed either became friendly or so weakened that they ceased to be a threat.

By contrast, during the same period, the Tirpitz plan transformed British perceptions of Germany. Tirpitz, as we have seen, explicitly justified his country’s naval build up with reference to Britain, the country that, as he put it, was ‘the most dangerous naval enemy’ and ‘also the enemy against which [Germany] most urgently require[d] a certain measure of naval force as a political power factor.’[12] However, it was not his intention that this should be made public; rather, he hoped that his true intentions could be masked by regular expressions of Germany amity until his ‘risk fleet’ was a reality and it was too late for Britain to do anything other than bow to Germany’s international ambitions. Unfortunately for Tirpitz, Britain’s Naval Intelligence Department was not so easily deceived. As early as December 1900, its astute director, Rear-Admiral Reginald Custance (1847-1935), had identified the German navy as the main rival of the future. As he subsequently put it: ‘the German Navy will be the most formidable force that this country will have to meet in the future ... We shall have to fight for the command of the North Sea, as we did in the Dutch Wars of the 17th Century.’[13] Given that the NID was responsible both for threat assessment and naval planning, this conviction inevitably led to detailed studies of war against Germany and then to the drawing up of systematic plans for naval operations against this power. Initially, these were additional to the schemes devised for war against France and Russia, countries still seen as likely opponents, but as the power political realities in Europe altered, so Germany rose to become the principal potential enemy and the plans for war against it became paramount to the Royal Navy’s operational thinking.

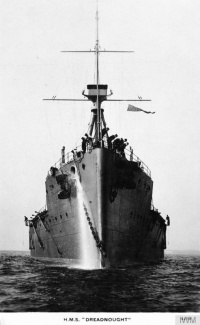

The parameters of a naval war against Germany looked very different than those inherent to one against France and Russia. Most obviously, the main theatre of conflict shifted from the Mediterranean to the North Sea. This necessitated a re-organization of the country’s naval assets. Prior to 1902 the main fleet had been in the Mediterranean and the so-called Channel Squadron, although based on the south coast, was actually the wartime reinforcement for the former. At the start of conflict, it would sail south, meaning that there was effectively no permanent fleet in British waters. This changed in 1902 with the creation of the Home Fleet, a force which Custance explicitly stated was needed to counter the threat from Germany. In December 1904, another redistribution would further strengthen the Royal Navy in home waters, a process that would continue in 1905 and, indeed, in the years thereafter, until nearly all the major units of the Royal Navy were stationed close to the North Sea.[14]

The identification of the North Sea as the likely future battle ground and the gradual accretion of assets there placed an enormous conglomeration of naval power in direct proximity to Germany. Admiral Sir John Fisher (1841-1920), the First Sea Lord, regarded this more as a way to prevent war with Germany than to prepare for it. He saw the Royal Navy as a deterrent that would give pause to Britain’s enemies. Consequently, whenever confrontation loomed, he deployed it as ostentatiously as possible at the enemy’s most vulnerable point in order to send out an unmistakeable military-political message. For example, when during the First Moroccan Crisis of 1905 an Anglo-German conflict seemed possible, Fisher sent the Channel Fleet to the Baltic to drive home to the decision-makers in Berlin that the sea through which vital trade with Scandinavia was conducted was not beyond Britain’s reach. While the message was understood on this occasion, this could not always be guaranteed and so, although deterring war with Germany was a vital mission, planning for it could not be ignored. This was less straightforward than it seemed. Ideally, as soon as war began, the German fleet would sortie from its defended anchorages and give battle. However, given the considerable superiority of the Royal Navy over its German counterpart, there was little incentive for the Germans to commit suicide in this fashion. What seemed more likely, especially after the Japanese had demonstrated the viability of such an approach at Port Arthur in 1904, was that the Germans might begin a war against Britain with a sudden surprise attack by torpedo craft on British warships at anchor. Accordingly, the British plan was to base its major warships out of range of German torpedo craft and to bring them into German waters only following news of a German advance. To ensure that this intelligence would be provided at the earliest possible moment, the Royal Navy planned to mount an observational blockade of the German coast. Destroyers would be dispatched to the enemy’s littoral, where they would watch for any sortie, report it once it had occurred and so enable British forces to be vectored against the enemy. If the Germans did not come out, this was potentially a long and arduous mission, but it did have one distinct benefit. Destroyers so placed were not only capable of mounting a military blockade; under international law their presence also provided a legal basis for a commercial blockade and the interdiction of vital imports into Germany. In the long run, many naval strategists believed that this would seriously harm the German economy. As Sir Charles Ottley (1858-1932), a former Director of Naval Intelligence, then Secretary to the Committee of Imperial Defence, explained in 1908:

Whether this would be sufficient to bring the Germans to sue for peace was questionable. Ottley thought it would; others, such as Sir Arthur Wilson (1842-1921) and Sir Edmond Slade (1859-1928), were less certain.[16] However, what commanded more consensus was the idea that it might create enough public pressure to force the German fleet to sea in the attempt to break the blockade. This, in turn, would bring about the battle the Royal Navy desired. Accordingly, economic pressure became a key component of British plans against Germany.

Economic warfare and battle were not the only tools in the navy’s armoury. Another application of command of the sea was the ability to transport troops over water and land them in the place of one’s choosing. For some naval leaders, Fisher in particular, ‘coastal military expeditions in pure concert with the Navy’ were considered a particularly promising way of applying force to Germany. As he explained in March 1909, a small raid ‘only involving 5,000 men and some guns, and horses’ might be ‘a mere fleabite,’ but, as he went on, ‘a collection of these fleabites would make Wilhelm scratch himself with fury!’[17] And that was not the only advantage of amphibious warfare. Blockading the German coast put extensive pressure on the Navy’s destroyers, which would have to make regular round trips from their bases in Britain to the German Bight. The capture of a German island, however, would provide these vessels with places to shelter, replenish, and refuel that were close to their zone of operations. Blockade would become that much easier. Little wonder that assaults on German islands were subject to regular study by the NID. However, whatever the potential of such seizures, the problem was that amphibious actions required the cooperation of the army and, as we shall see, this was far from guaranteed.

At the same time as the Royal Navy was re-orientating its plans away from France and Russia and towards Germany, a similar process was taking place in the British Army. However, while the General Staff came to the same conclusion as the Admiralty regarding the identity of Britain’s most likely future adversary, they had quite a different conception of what such a war would look like and how Britain might fight it. In part, this was because the army was redefining its mission. Deployed to South Africa in 1899 to fight two small and militarily insignificant Boer republics, the army had begun the Second South African War with a string of humiliating defeats. Although the conflict was ultimately brought to a victorious conclusion, the process was slow and difficult. That the army was neither properly organized nor suitably proficient seemed self-evident. Reform quickly followed. The changes dealt with the deficiencies that had been revealed in South Africa, producing a fitter, leaner, and better-led force, but alongside this came a new aspiration. Those who now found themselves in command were no longer content to prepare for home defence, small colonial wars and amphibious raids; they instead sought to mould an army capable of the ultimate test, fighting in continental Europe against one of the great military powers. Thus, when Germany was identified as the most likely future enemy, the General Staff proposed to dispatch soldiers to France where they could assist in stemming the anticipated German advance. While this might stave off defeat, just how it would win a war was never spelt out. Nevertheless, this expeditionary warfare strategy, generally known in the historiography as the ‘continental commitment,’ would be the basis for all the army’s subsequent plans.

That there was a basic incompatibility between the army and navy’s plans was clear. Little, however, was done to resolve this. A meeting of the Committee of Imperial Defence was held in August 1911 at which the army, represented by Director of Military Operations Sir Henry Wilson (1864-1922), showcased its plans and the Navy, represented by First Sea Lord Sir Arthur Wilson, presented its alternative. Sir Henry was a much better advocate than Sir Arthur and the assembled ministers went away impressed by the eloquence of the former and horrified by the seeming incoherence of the latter.[18] It has frequently been argued that this disparity led the government to dismiss the navy’s plans and endorse the army’s.[19] In reality, while Sir Arthur Wilson’s reputation received a severe knock and the Admiralty was obliged to guarantee that any British troops sent to France would be properly protected en route, no decision was made on national strategy. The two services continued to prepare their own plans according to their own agendas. In the army’s case this meant continuing as before; in the navy’s it involved an important change.

Until the end of 1911, the NID remained committed to mounting an observational blockade of the German coast. Regular manoeuvres alongside evaluations of Germany’s defences indicated that while this would not be easy, it was a manageable operation. However, in early 1912, the upgrading of Germany’s coastal fortifications, the enhancement of their submarine forces and a reassessment of the danger from mines induced a change in the navy’s thinking. Observational blockade was now deemed too risky. Instead, the Admiralty proposed a ‘distant blockade.’ By controlling the entrances to the North Sea, German forces would be confined to their own waters and German trade would be interdicted through the control of contraband goods. The problem was that the dispositions envisaged to support this – placing the Grand Fleet far to the north – would leave the east coast exposed to German attack. While no satisfactory solution to what became known as ‘the North Sea problem’ had been reached by 1914, the reconfiguration of British plans went ahead anyway.[20]

Thus, according to most historians, on the eve of war in 1914, the British armed forces had two distinct plans for war. The army wished to send troops to the continent to fight alongside the French; the navy would use economic warfare to force the German fleet to battle or cripple the German economy if the ships refused to come out and fight. Both plans would see the light of day in the First World War.

This interpretation of British war planning has received widespread acceptance because it seems to fit the facts and to be validated by what actually occurred when war broke out. However, it has come in for extensive criticism from a small group of revisionist historians who challenge almost every element of it.[21] To begin with, they argue, the German naval build up did not lead to a reassessment of Britain’s geo-strategic position. The German navy, they maintain, lacked the capability to strike at Britain and the British authorities knew this; the actual source of anxiety, especially in the Admiralty, was the prospect of French and Russian armoured cruisers attacking British seaborne trade. A threat such as this could not be met by the kind of deployment described in the traditional historiography with its focus on Germany. Not surprisingly, therefore, the revisionist literature posits quite different British war plans. In the realm of defence, the Royal Navy planned to secure the homeland by deploying swarms of small torpedo craft, such as destroyers and submarines, to make the waters around British Isles impassable; while at the same time protecting the trade routes from the depredations of foreign raiders with battle cruisers. As regards offence, the Admiralty did not propose to conduct economic warfare in the traditional sense of slowly strangling an opponent’s trade; rather the naval authorities advocated using Britain’s position as the leading financial hub to win a quick war by collapsing the global economy and so destroying the ability of Britain’s enemies to wage war.

These theories are eye-catching, but the evidence for them is scant and the rebuttals obvious. The German threat, for example, did not need to be invented because the Reich’s political ambitions and the implications of these for Britain were all too real. Under the Tirpitz plan, however flawed it might have been, the German navy was deliberately being built to challenge Britain and the British authorities were in receipt of ample intelligence that reliably informed them of this fact. By contrast, Russia’s armoured cruisers were no threat because they had been sunk in the Russo-Japanese War and the French ones were inferior vessels that were both outnumbered and outperformed by their British equivalents. Second, without denying the importance of submarines, destroyers, and battle cruisers to modern naval warfare, at no stage did those charged with Britain’s defence decide to rely on them to safeguard British interests. The fact that at vast expense 32 dreadnought battleships had been commenced before the outbreak of the First World War and that all of them were routinely in British ports is visible testament to their central role in national defence. Finally, not only is it counter-intuitive to suggest that the world’s greatest commercial power would collapse the global economy – the source of all its wealth and power – as a deliberate strategy, it also runs counter to the documentary evidence. The British war book, for example, in which were carefully listed the responsibilities of the various government departments in wartime, makes clear that economic warfare was still conceived on traditional lines, that is to say slow-acting pressure brought about mainly through the interdiction of commerce.[22]

Some External Influences and Complications↑

While the planners in Berlin and London perfected their schemes for operations in north-western Europe and its adjacent waters, the intentions and likely actions of other powers, both friendly and hostile, served as a complicating factor that compelled these planners, sometimes reluctantly, to pay attention to other theatres. Their success in so doing largely depended upon their willingness and ability to work with others.

For the officers of the Prussian Great General Staff the complicating factor with the greatest potential for disrupting their plans was the attitude of their Austro-Hungarian counterparts in the Imperial and Royal General Staff. The Habsburg Empire, like Germany, was a central European country that bordered directly onto a series of potentially hostile military powers. These included Russia to the northeast, Serbia, Montenegro, and Rumania to the south and Italy, nominally an ally, but actually a rival, to the west. As a result, Austria-Hungary, no less than Germany, had to assume that any conflict in which it was engaged would either start as or would very quickly degenerate into a war on multiple fronts. To meet this tricky strategic situation, the Imperial and Royal General Staff devised contingency arrangements for all the most likely scenarios. For our purposes, the details are less important than the main consequence, which was that, while minimal defensive forces could be mustered to cover all of the vulnerable frontiers, the capacity for substantial offensive action was largely limited to the one front where the bulk of the Habsburg army would be deployed. Which front this would be was a matter of strategic choice. For political reasons, namely enhancing their authority in the Balkans, the Habsburg authorities would have preferred to deploy principally to the south against Serbia, the country most actively undermining their status in the region. However, as such a move was certain to be opposed by Russia and, as the Austrian leadership was rightly worried about their ability to meet the military threat from the east, Vienna looked to Germany to offset this difficulty either by deterring St Petersburg from taking action in the first place or, if that failed and war arose anyway, by deploying such forces on the Polish border as would so occupy the Russian army that they could not strike meaningfully at Austria. Herein, however, lay a major problem for Germany’s leaders. Given that they planned to send the bulk of their military might westward against France, it was not only clear that they could not do as Vienna desired, but, in addition, they were hoping that the Austrian army would act as the distraction, preventing Russia from concentrating on Germany. Thus, the desire in Berlin was that Vienna would make Galicia rather than the Balkans the key Austrian front. Saying so explicitly was, however, problematic, as there was every chance that if the Austrian authorities knew for certain that at the start of a war Germany would offer no substantial support in the east, they might baulk at military action entirely. Moltke certainly thought so, arguing in 1912 that ‘without Germany’s help Austria will remain purely on the defensive.’[23] Given these contradictions in basic strategy, reconciling them through joint planning should have been a top order priority. However, this would evidently not have been easy and, instead of rising to the challenge, the military leaders of the two powers preferred to avoid such potentially difficult conversations and maintained instead a high level of constructive ambiguity in those conversations that actually took place. As a result, there was no meaningful coordination between the two powers. The price of this would be paid in September 1914.

If the Balkan and Russian frontiers posed problems for German and Austrian military planners, for those coordinating naval strategy in Paris and London a comparable source of difficulty was the Mediterranean. For France, the Mediterranean was of enormous strategic importance. It was not just that the country possessed a long Mediterranean coastline that needed to be defended; it was also the case that this sea served as the transit route for an important element of the French army. To facilitate control of their empire, the Republic based an entire army corps – the XIX corps, sometimes known as the Army of Africa – in Algeria. While this made perfect sense in peacetime, in the event of war with Germany this unit was needed for frontline service on the French mainland. Yet, given that troop transports were extremely vulnerable, this could only happen if command of the western Mediterranean was in their hands and to this end, even after the ending of the Anglo-French naval rivalry, a force of battleships was maintained there to ensure this.

For Britain no less than France the Mediterranean was a vital conduit acting both as a key trade route and also as an essential artery of empire between the metropolis and Britain’s holdings in the Asian subcontinent and the Far East. For this reason, despite the ever-increasing concentration on the German threat and the corresponding emphasis on home waters, the Royal Navy had never abandoned this sea, but had maintained a tangible presence there, albeit in the form of a fleet composed of pre-dreadnought battleships.

This status quo would not, however, endure. In June 1909 Italy laid down its first dreadnought and followed this up by ordering three more. Austria-Hungary then did likewise, laying down four of its own. The first of these new ships was due to come into service at the end of 1912. This Italo-Austrian shipbuilding spree had major implications. Once these new warships were in service, the Royal Navy’s pre-dreadnoughts would no longer be able to maintain Britain’s age-old dominance of the region. Equally, the French government was haunted by the possibility that once these vessels were competed, should Austria and Italy act in concert, as their alliance theoretically mandated, then their combined force would be in a strong position to contest French sea control of the western Mediterranean and prevent France from bringing its Algerian army home.

For both Entente powers, therefore, the new strategic reality in the Mediterranean forced them to reconsider their existing plans. For the British, the question was what force, if any, should be deployed in the Mediterranean. The Admiralty wanted to withdraw all capital ships in order to concentrate on the North Sea. However, the Foreign and Colonial Offices countered that this would do irreparable damage to British prestige in the region, especially in Egypt, while the army, fearful that they would have to provide larger garrisons to British possessions there, asserted that this would ‘put a strain upon our military resources which, at their present strength and under their existing organisation, they are quite unable to bear.’[24] The result was a commitment to stationing a modest force of battle cruisers in the Mediterranean. While this would be sufficient to maintain Britain’s status as a Mediterranean power, it would not be sufficient to enable the Royal Navy to dominate the entire sea. At best, British interests in Egypt and the eastern basin might be protected from Malta. For the French naval command, the absolute imperative of getting the XIX corps safely to France meant concentrating all forces on ensuring their safety. This required a focus on the western basin and a willingness to base the strongest possible force there. It did not take long for the planners in London and Paris to realise that their Mediterranean predicaments were similar, even complementary, and that for both careful coordination would mitigate the worst aspects of the situation. The result was what amounted to an Anglo-French arrangement for the Mediterranean. In contrast to the Austro-German failure of joint planning, Britain and France agreed to divide up responsibility for the Mediterranean. In 1914, despite the fiasco of the escape of the Goeben to Constantinople, both powers’ interests were therefore maintained. France was able to transport its army corps from Algeria and control of the Mediterranean was never seriously challenged by the Central Powers.

Conclusion↑

Both German and British war planning have been very active areas of research and controversy. Neither the research nor the controversy shows any signs of abating. As a result, we can expect many more ideas to appear in these areas in coming years. For now, however, the state of the discipline is clear. A consensus has been reached that, while the more extreme revisionist claims in both areas are untenable, the issues are more complex than was once thought.

Matthew S. Seligmann, Brunel University London

Section Editors: Annika Mombauer; William Mulligan

Notes

- ↑ The classic study is Steinberg, Jonathan: Yesterday’s Deterrent: Tirpitz and the Birth of the German Battle Fleet, New York 1965.

- ↑ The main exceptions are Gemzell, Carl-Axel: Organization, Conflict, and Innovation: A Study of German Naval Strategic Planning, 1888-1940, Lund 1973; Lambi, Ivo N.: The Navy and German Power Politics, 1862-1914, London, 1984.

- ↑ Dülffer, Jost: Limitations on Naval Warfare and Germany’s Future as a World Power: A German Debate, 1904-6, in: War and Society 3 (1985).

- ↑ Seligmann, Matthew S.: The Royal Navy and the German Threat, 1901-1914: Admiralty Plans to protect British Trade in a War against Germany, Oxford 2012.

- ↑ = Morgan-Owen, David: An “Intermediate Blockade”? British North Sea Strategy, 1912–1914, in: War in History 22/4 (2015). =

- ↑ See, for example, Kuhl, Hermann von: Der deutsche Generalstab in Vorbereitung und Durchführung des Weltkrieges, Berlin 1920; Foerster, Wolfgang: Graf Schlieffen und der Weltkrieg, Berlin1921; Ritter, Gerhard: Der Schlieffenplan: Kritik eines Mythos, Munich 1956; Craig, Gordon: The Politics of the Prussian Army, Oxford 1964; Kitchen, Martin: A Military History of Germany, Bloomington, IN 1975; Turner, L.C.F.: The Significance of the Schlieffen Plan, in: Kennedy, Paul M. (ed.): The War Plans of the Great Powers, London 1979, pp. 199-221.

- ↑ Förster, Stig: Dreams and Nightmares: Germany Military Leadership and the Images of Future War, 1871-1914, in: Boemeke, Manfred F. / Chickering, Roger / and Förster, Stig, (eds.): Anticipating Total War: The German and American Experiences 1871-1914, Cambridge 1999.

- ↑ See, for example, Holmes, Terence M.: The Reluctant March on Paris: A Reply to Terence Zuber’s “The Schlieffen Plan Reconsidered,” in: War in History 8/2 (2001); Foley, Robert T.: The Origins of the Schlieffen Plan: Debate, in: War in History 10/2 (2003).

- ↑ Zuber, Terence: The Schlieffen Plan Reconsidered, in: War in History 6/3 (1999), p. 305.

- ↑ Gross, Gerhard P.: There Was a Schlieffen Plan: New Sources on the History of German Military Planning, in: War in History 15 (2008).

- ↑ Morgan-Owen, David G.: The Fear of Invasion: Strategy, Politics and British War Planning 1880-1914, Oxford 2017.

- ↑ The Tirpitz Memorandum of June 1897 is quoted in full in Steinberg, Yesterday’s Deterrent 1965, pp. 209-221. This excerpt is from p. 209.

- ↑ Memorandum by Custance on Report of Financial Secretary, 5 November 1902. Quoted in Seligmann, Matthew S. / Nägler, Frank / and Epkenhans, Michael (eds.): The Naval Route to the Abyss. The Anglo-German Naval Race, 1895-1914, Navy Records Society 2015.

- ↑ Seligmann, Matthew S.: A Prelude to the Reforms of Admiral Sir John Fisher: The Creation of the Home Fleet, 1902-1903, in: Historical Research 83 (2010).

- ↑ Ottley to McKenna, 5 December 1908. Quoted in Marder, Arthur: From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow Vol. I: The Road to War 1904-1914, Oxford 1961, p. 379.

- ↑ Seligmann, Matthew S.: Failing to Prepare for the Great War? The Absence of Grand Strategy in British War Planning before 1914, in: War in History 24/4 (2017).

- ↑ Fisher to Esher, 15 March 1909. Quoted in Marder, Arthur (ed.): Fear God and Dread Nought: The Correspondence of Admiral of the Fleet Lord Fisher of Kilverstone, 3 Volumes, London 1952-9, II, pp. 232-3.

- ↑ Williamson, Samuel R. Jr.: The Politics of Grand Strategy: Britain and France Prepare for War, 1904-1914, Cambridge, MA 1969, pp. 187-93; Marder, Arthur: From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow, Volume I: The Road to War 1904-1914, Oxford 1961, pp. 244-5; d’Ombrain, Nicholas: War machinery and High Policy: Defence Administration in Peacetime Britain, 1902-1914, Oxford 1973, pp. 110-102.

- ↑ See, for example, Morris, A.J.A.: The Scaremongers: The Advocacy of War and Rearmament, 1896-1914, London 1984, pp. 302-3.

- ↑ Seligmann, Failing to Prepare for the Great War? 2017.

- ↑ See especially Sumida, Jon T.: In Defence of Naval Supremacy: Finance, Technology and Naval Policy, 1889-1914, London 1989; Lambert, Nicholas A.: Sir John Fisher’s Naval Revolution, Columbia, SC 1999.

- ↑ See Committee of Imperial Defence, Coordination of Departmental Action. War Book (1914 Edition). TNA: CAB 15/5.

- ↑ Ritter, Schlieffen Plan 1956, p. 68, note 60.

- ↑ Memorandum by the General Staff on the Effect of the Loss of Sea Power in the Mediterranean on British Military Strategy, 1 July 1912. TNA: CAB 4/4/33.

Selected Bibliography

- Bell, Christopher M.: Sir John Fisher’s naval revolution reconsidered. Winston Churchill at the admiralty, 1911-1914, in: War in History 18/3, 2011, pp. 333-356.

- Dunley, Richard: Invasion, raids and army reform. The political context of ‘flotilla defence’, 1903-5, in: Historical Research 90/249, 2017, pp. 613-635.

- Dunley, Richard: Sir John Fisher and the policy of strategic deterrence, 1904-1908, in: War in History 22/2, 2015, pp. 155-173.

- Epkenhans, Michael: Tirpitz. Architect of the German high seas fleet, Washington, D.C. 2008: Potomac Books.

- Foley, Robert T.: The origins of the Schlieffen Plan, in: War in History 10/2, 2003, pp. 222-232.

- Förster, Stig: Dreams and nightmares. German military leadership and the images of future warfare, 1871-1914, in: Boemeke, Manfred F. / Chickering, Roger / Förster, Stig (eds.): Anticipating total war. The German and American experiences, 1871-1914, Washington, D.C.; Cambridge; New York 1999: German Historical Institute; Cambridge University Press, pp. 343-376.

- French, David: British economic and strategic planning, 1905-1915, London; Boston 1982: Allen & Unwin.

- Gemzell, Carl-Axel: Organization, conflict, and innovation. A study of German naval strategic planning, 1888-1940, Lund 1973: Esselte Studium.

- Grimes, Shawn T.: Strategy and war planning in the British Navy, 1887-1918, Woodbridge 2012: Boydell.

- Groß, Gerhard P.: There was a Schlieffen Plan. New sources on the history of German military planning, in: War in History 15/4, 2008, pp. 389-431.

- Halpern, Paul G.: The Mediterranean naval situation, 1908-1914, Cambridge 1971: Harvard University Press.

- Holmes, Terence M.: The reluctant march on Paris. A reply to Terence Zuber's 'The Schlieffen Plan reconsidered', in: War in History 8/2, 2001, pp. 208-232.

- Kelly, Patrick J.: Tirpitz and the Imperial German Navy, Bloomington 2011: Indiana University Press.

- Lambert, Nicholas A.: Sir John Fisher's naval revolution, Columbia 1999: University of South Carolina Press.

- Lambert, Nicholas A.: Planning armageddon. British economic warfare and the First World War, Cambridge; London 2012: Harvard University Press.

- Lambi, Ivo Nikolai: The navy and german power politics, 1862-1914, Boston 1984: Allen and Unwin.

- Marder, Arthur Jacob (ed.): Fear God and dread nought. The correspondence of Admiral of the Fleet Lord Fisher of Kilverstone, 3 volumes, London 1952-1959: J. Cape.

- Mombauer, Annika: Helmuth von Moltke and the origins of the First World War, Cambridge; New York 2001: Cambridge University Press.

- Morgan-Owen, David G.: The fear of invasion. Strategy, politics, and British war planning, 1880-1914, Oxford 2017: Oxford University Press.

- Overlack, Peter: The function of commerce warfare in an Anglo‐German conflict to 1914, in: Journal of Strategic Studies 20/4, 1997, pp. 94-114.

- Ritter, Gerhard: The Schlieffen plan. Critique of a myth, London 1958: Oswald Wolff Ltd.

- Röhl, John C. G.: Wilhelm II. Into the abyss of war and exile, 1900-1941, Cambridge 2014: Cambridge University Press.

- Schlieffen, Alfred, Foley, Robert (ed.): Alfred von Schlieffen's military writings, London; Portland 2003: Frank Cass.

- Seligmann, Matthew S.: Failing to prepare for the Great War? The absence of grand strategy in British war planning before 1914, in: War in History 24/4, 2017, pp. 414-437.

- Seligmann, Matthew S.: The Royal Navy and the German threat, 1901-1914. Admiralty plans to protect British trade in a war against Germany, Oxford 2012: Oxford University Press.

- Seligmann, Matthew S.: Spies in uniform. British military and naval intelligence on the eve of the First World War, Oxford; New York 2006: Oxford University Press.

- Snyder, Jack L.: The ideology of the offensive. Military decision making and the disasters of 1914, Ithaca 1984: Cornell University Press.

- Weir, Gary E.: Building the Kaiser's navy. The Imperial Navy Office and German industry in the von Tirpitz era, 1890-1919, Annapolis 1992: Naval Institute Press.

- Williamson, Jr., Samuel R.: The politics of grand strategy. Britain and France prepare for war, 1904-1914, Cambridge 1969: Harvard University Press.

- Zuber, Terence: Inventing the Schlieffen Plan. German war planning, 1871-1914, Oxford; New York 2002: Oxford University Press.

- Zuber, Terence: The Schlieffen Plan reconsidered, in: War in History 6/3, 1999, pp. 262-305.