Introduction↑

The divisions that the Great War opened up in Australian society lived on into the post-war era, shaping repatriation, politics, commemoration, and social life. The war had widened the fissures between the classes as well as between Protestant and Catholic denominations. The Easter uprising in Dublin (1916) and the Russian Revolution (1917) – followed by civil war in each case – helped extend wartime divisions over class, religion and empire into the interwar period. The deadly Spanish influenza pandemic, which killed 30 million around the world, took the lives of about 12,000 Australians.[1]

The tone of post-war Australian society has been most famously evoked by D.H. Lawrence (1885-1930) in Kangaroo (1923), a novel about returned soldiers’ involvement in a secret army. The book was the result of his brief visit to Australia with his wife Frieda Lawrence (1879-1956) in 1922. George Johnston’s (1912-1970) autobiographical novel My Brother Jack (1964) was also set in post-war Australia, in this case in Melbourne, as was Graham McInnes’s (1912-1970) memoir The Road to Gundagai (1965).

Anzacs Return↑

It took over a year for the men of the Australian Imperial Force to return home.[2] This was, for many of these citizen-soldiers, a time of frustration. They were returning to a society that, especially for those who had enlisted early in the war, was greatly changed from the one left behind. Such changes were experienced at the individual level. The war had been unkind to the Australian economy and jobs were scarce.[3] The country experienced a wave of strikes as unions sought to make up for lost wages and conditions. Families, too, had changed. Girlfriends and even wives had sometimes moved on; a familiar trope in “digger” (Australian soldier) popular culture of this era is the returned man betrayed at home by a disloyal lover, with a “shirker” or “profiteer” being the new recipient of her favour. Yet many returned men posed a greater danger to the happiness and well-being of women than the other way around, since there were very high rates of venereal disease in the Australian forces, posing a risk to the families to which the men returned.[4] Newspapers also drew attention to street and domestic violence involving returned soldiers which gave the impression that it had become more frequent. The number of divorces more than doubled between 1913 and 1921.[5]

For all the interest of recent historiography in dislocation and trauma, large numbers of men readily settled back into civilian life and did their best to take up where they had left off. The war, however, undoubtedly altered the shape of family life and gender relations. With the number of casualties among men of marriageable age, there were reduced opportunities for marriage among younger women, as well as an unusually large number of young widows during the 1920s and 1930s. Many thousands of children grew up in homes headed by a woman. Even in households to which men had returned, their ability to exercise authority might have been reduced by physical incapacity or psychological damage. Many died prematurely, their names unrecorded on the Australian War Memorial’s roll of honour if their passing occurred after 1921.

Returned men were involved in the public violence of 1919 that was a pale reflection of European turmoil. Diggers engaged in collective protest that expressed their sense of dissatisfaction either with their own treatment or with the “disloyal” behavior of others. In Brisbane in March, returned soldiers were prominent among rioters who responded to a leftist “red flag” rally by attacking members of the local Russian community. Not all soldier violence, however, was directed against the left. At the Western Australian port of Fremantle in May, conflict led to a violent clash between strike-breakers accompanied by the conservative premier, Hal Colebatch (1872-1953), and unionists and their supporters – in some instances returned soldiers. Several people were injured and a unionist was killed. In July there were wild riots of returned soldiers in Melbourne. They stormed the offices of the state government, with one rioting digger smashing an inkstand over the head of the conservative premier, “drenching him in blood”. In December returned soldiers from Melbourne travelled to western Victoria and abducted and then tarred and feathered J.K. McDougall (1867-1957), a farmer, poet, and retired federal parliamentarian whom they accused of disloyalty.[6]

Anzacs Organise↑

The Returned Sailors’ and Soldiers’ Imperial League of Australia (RSSILA) – later the Returned and Services League (or RSL) – has sometimes been given the credit or blame for directing the politics of Australia’s returned soldiers into conservative channels. Many of the RSSILA’s leaders were former officers and some had strong connections with the non-Labor parties. Especially after the Catholic Gallipoli veteran Gilbert Dyett (1891-1964) became its national president it focused, with considerable success, on gaining concessions for returned soldiers.[7]

Prime Minister William Morris “Billy” Hughes (1862-1952), who remained in his post until early 1923, continued to cultivate his image as “the little digger”, recognized the soldier vote as potentially potent, and was sympathetic to the claims returned men made on the society that had sent them to war. Australia developed a generous system of entitlements for returned men and their families – medical care, artificial limbs, pensions for the disabled and for dependents, war service homes, soldier settler blocks, educational assistance for children, training for ex-diggers – although with considerable emphasis on encouraging such men to support themselves.[8] Still, by the late 1930s, 250,000 Australians were receiving a war pension. In practice, many of the most damaged among the 150,000 or so casualties were supported by their families, with a heavy burden falling on wives and children.[9]

Perhaps because it had been so successful, so early, in its efforts to gain government concessions, the RSSILA had difficulty attracting, and then keeping, members. It probably had between 100,000 to 120,000 members in 1919, but its numbers declined thereafter, before beginning a slow recovery.[10] The diverse political leanings and industrial loyalties of many returned men confounded efforts to create a bloc of soldiers’ votes.

Commemoration↑

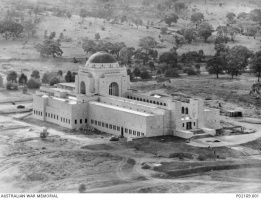

Local communities as well as governments organised to build memorials to Australia’s 60,000 war dead and to the hundreds of thousands more who had returned, sometimes with severe disabilities or psychological scars that would remain with them for life. Historians have credited Australia’s maintenance of a voluntary system of recruitment throughout the war (as a result of the defeat of the two efforts to introduce conscription by referendum) with the unusual practice of including the names of returned men (and, sometimes, the few women serving as nurses) on many of the memorials.[11] Memorials took many different forms: a soldier resting on reverse arms, an obelisk, an arch or a cross; or, in the case of utilitarian memorials, a clock tower, fountain or hall. Such memorials appeared across the country, often serving as the focus of Anzac Day ceremonies on 25 April each year, as well as Remembrance Day on 11 November. In the state capital cities, larger memorials were built, often through a mixture of public subscription and government funding. In the city of Canberra, which became the seat of government in 1927, the war correspondent and official historian Charles Bean (1879-1968), played the key role in creating the Australian War Memorial, a massive byzantine edifice that opened in 1941.[12] Not everyone’s sacrifices received equal recognition in this wave of memorialisation. During the war itself, there was much emphasis in public rhetoric on the mother who sacrificed her son; after the war, the sacrifices that such women had made became hard to discern in commemorative ritual and memorial construction.[13]

Anzac Day – the anniversary of the day Australian soldiers stormed the cliffs of Gallipoli – was often the occasion for the unveiling of such memorials. It emerged after the war as a major occasion of commemoration, even being acclaimed as Australia’s national day. It was also increasingly claimed by returned soldiers as their own. By the end of the 1920s all state governments had declared the day a public holiday of one kind or another, given over to various forms of commemoration. A dawn service and a march were its most prominent rituals, but some places staged commemorative sporting events and the afternoon was given over to various forms of informal conviviality among returned men, with drinking and gambling prominent. There was an apparent shift in emphasis from a day of mourning to more of a nationalistic celebration of wartime achievement and the virtues of the Anzacs but the meaning of Anzac Day would always remain contested.

A Caste Apart↑

Notwithstanding widespread pride in the performance of Australian soldiers and a developing consensus that the nation had been born at Gallipoli, the Anzac legend enjoyed only a limited success in forging national unity. Returned soldiers were, in many respects, a divisive force in post-war Australian society.[14] All of Australia’s servicemen had been volunteers; it was perhaps not surprising that they should regard themselves as a group with special rights, a caste apart. The federal government’s policy of preference to returned servicemen in public service employment encouraged this perception. Moreover, private employers were encouraged to give the returned men preference. One consequence was that there was conflict between returned servicemen and trade unions, which contributed to an existing impression that the Labor Party was not completely loyal to the British Empire.

Parallel systems of welfare had also emerged by the 1920s: one for ordinary people, one for returned soldiers. Before the war, Australia had been developing a rudimentary welfare state; afterwards, this project faltered so far as ordinary civilians were concerned and would not be resumed until the Second World War. One reason for this hiatus might well have been the need to develop a new welfare system for returned servicemen and their dependents.[15]

Returned soldiers were a significant presence in right-wing organizations and paramilitaries formed during the interwar years to fight “the enemy within”, such as union militants, unemployed workers, Irish, Germans, Communists, and Jack Lang (1876-1975), the radical New South Wales Labor Premier. These secretive organizations were led by very wealthy businessmen - sometimes ex-senior army officers - who had much to lose in the event of a social breakdown. They drew much of their support from the country, but were largely directed from the city offices of their leaders.[16]

The methods of the New Guard were rather different. It was no secret, actively seeking publicity. Formed during the depression by Lieutenant-Colonel Eric Campbell (1893-1970), the New Guard drew most of its support from Sydney’s middle class and attracted about 40,000 members, many of them ex-soldiers who were organized along paramilitary lines and employed violence to break up meetings of radicals.[17]

Soldier Settlement↑

One remedy offered by governments to deal with both the restlessness of many returned soldiers and their need to support themselves was soldier settlement. Its aim was to place a large number of returned soldiers on the land so that they might become sturdy farmers. Anzac heroes, who had proved themselves natural soldiers, would supposedly prove natural farmers even if they had spent much of their lives in the cities. Soldier Settlement Acts placed about 40,000 settlers on the land; when the families whose labor proved so critical to soldier settlement are included, the scheme probably involved over 100,000 men, women, and children.[18] State governments purchased allotments of land which it allocated to the soldiers. While soldier settlement succeeded in some circumstances, there were many tragic cases of failure, the result of land that was poor in quality or inadequate in size, a lack of capital and expertise, and the ailments that so many suffered as a legacy of their service. Many felt that they had been cheated by government when they had to abandon their efforts at independence and look for a living elsewhere.[19]

Gains and Losses↑

Hughes gained what he thought of as Australia’s deserts at Versailles in 1919, notably control of many former German territories in the Pacific, especially German New Guinea, which was added to Australia’s existing territory in Papua. He successfully opposed an effort by Japanese delegates to have a racial equality clause inserted in the League of Nations covenant. These preoccupations reflected a political class increasingly concerned with external threats in a world that seemed ever more dangerous to a thinly populated white settler nation located thousands of miles from the center of British imperial power. Pre-war Australia, while apprehensive about the rise of Japan, then a British ally, the intensification of imperial rivalries, and the arms race in Europe, nonetheless had an optimistic tone. The early years of federation had been a time of political experimentation in which Australia gained a reputation as a social laboratory. In the cultural sphere, moreover, there had been considerable interest in modernism.

Several historians have seen the war as bringing this phase of Australian development to a close, helping to produce a more repressive, pessimistic, and inward-looking society.[20] There was now a tendency among some intellectuals to regard modern European artistic and literary movements as a foreign infection. Art which did not express the nation’s soul was inferior; conservative landscape painting was held up as the style and subject best fitted for this role. One historian referred to this phase as a “cultural quarantine”.[21]

Recovery↑

By the early 1920s, however, the worst of post-war dislocation seemed to be over. The economy had stabilized, although demand for many of the products that Australia had to offer the world was precarious and unemployment would never drop below six percent for the remainder of the interwar years and was usually much higher. Still, by the mid-1920s, many Australians were beginning to enjoy a greater comfort than they had previously known: there were new household appliances, car ownership was spreading, the radio was becoming central to home entertainment while the cinema opened up to Australians a wider, more exotic, and more glamorous world. These comforts and pleasures were not spread evenly. It would be a long time before car ownership became common among the working classes, while Aboriginal people of the 1920s remained marginalized and often at the behest of bureaucrats who controlled almost every aspect of their lives. Such officials were soon advocating the whitening of the population by a program of controlled mating between mixed race indigenous women and white men that would “breed out the colour’. Meanwhile, children were taken from their families and installed in institutions to prepare them for a lowly place in mainstream – or white – society.[22]

The rise of a new force in politics at the end of the war, the Country Party, resulted in the fall of William Morris Hughes as prime minister at the beginning of 1923 and the emergence of a coalition between a largely urban-based Nationalist Party, led by Stanley Melbourne Bruce (1883-1967), and the Country Party under the leadership of Earle Page (1880-1961). Both Bruce and Page had served in the war; Bruce as a captain in a British regiment at Gallipoli – Australian-born, he had lived in England before the war – and Page as a doctor. Bruce walked with a limp, the legacy of a wound. In politics as in so many other spheres, war would extend its shadow for decades to come.

Conclusion↑

Post-war Australia was inevitably caught up to some extent in the turbulence and turmoil that occurred throughout the societies that had participated in World War I. For a country with a small population – fewer than 5 million in 1914 – Australia had put a large number of men in uniform – more than 400,000 – and it had suffered around 60,000 dead and more than 150,000 wounded.

The scars afflicting society itself were evidence beyond such calculations. A relatively united and cohesive young nation found itself more divided and less confident about its future as a small and largely white country sheltering under a somewhat more tattered British imperial umbrella. While Australia would not suffer anything like the same degree of violence or political break-down that marked so many European countries in the interwar years, the depression would take a pitiable toll. From September 1939 another world war, beginning just twenty years after the last had ended, would again engage Australians but in the context of a much more direct threat to the nation’s security.

Frank Bongiorno, The Australian National University

Section Editor: Peter Stanley

Notes

- ↑ Garton, Stephen and Stanley, Peter: The Great War and its aftermath, 1914-22, in: Bashford, Alison and Macintyre, Stuart (eds.): The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume 2: The Commonwealth of Australia, Cambridge 2013, pp. 55-6.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 55.

- ↑ Macintyre, Stuart: A Concise History of Australia, Second Edition, Cambridge 2004, p. 172.

- ↑ Bongiorno, Frank: The Sex Lives of Australians: A History, Collingwood 2012, pp. 129-32, 143-4, 152.

- ↑ McDonald, Peter/Ruzicka, Lado/Pyne, Patricia: Marriage, Fertility and Mortality’, in: Vamplew, Wray (ed.): Australians: Historical Statistics, Broadway, New South Wales 1987, p. 47.

- ↑ Bollard, Robert: In the Shadow of Gallipoli: The Hidden History of Australia in World War, Sydney 2013, ch. 8; Evans, Raymond: The Red Flag Riots: A Study of Intolerance, St. Lucia 1988; de Garis, Brian K.: An Incident at Fremantle, in: Labour History 10 (1966), pp. 32-7; Cathcart, Michael: Defending the National Tuckshop: Australia's Secret Army Intrigue of 1931, Fizroy, Victoria 1988, p. 91; King, Terry: The Tarring and Feathering of J.K. McDougall: “dirty tricks” in the 1919 federal elections, in: Labour History 45 (1983), pp. 54-67.

- ↑ Crotty, Martin: The Returned Sailors’ and Soldiers’ Imperial League of Australia 1916-46’, in: Crotty, Martin & Larsson, Marina (eds.): Anzac Legacies: Australians and the Aftermath of War, North Melbourne 2010, pp. 171-2.

- ↑ Garton, Stephen: The Cost of War: Australians Return, Melbourne 1996; Garton and Stanley, The Great War and its Aftermath 2013, p. 60.

- ↑ Garton and Stanley, The Great War and its Aftermath 2013, p. 160; Larsson, Marina: Shattered Anzacs: Living with the Scars of War, Sydney 2009.

- ↑ Crotty, The Returned Sailors’ and Soldiers’ Imperial League of Australia 2010, p. 176.

- ↑ Inglis, Ken and Phillips, Jock: War Memorials in Australia and New Zealand: A Comparative Study, in: Australian Historical Studies 24/96 (1991), pp. 179-191.

- ↑ Inglis, K.S. with Brazier, Jan: Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape, Carlton South 1999, esp. chs. 4 and 7.

- ↑ Damousi, Joy: The Labour of Loss: Mourning, Memory and Wartime Bereavement in Australia, Cambridge 1999; Luckins, Tanja: The Gates of Memory: Australian People's Experiences and Memories of Loss and the Great War, Fremantle 2004.

- ↑ McLachlan, Noel: Nationalism and the Divisive Digger: Three Comments, in: Meanjin Quarterly 27/3 (1968), pp. 302-308.

- ↑ Smith, F.B.: If Australia had not participated in the Great War?: An essay on the costs of war, in: Wilcox, Craig assisted by Aldridge, Janice: The Great War: Gains and Losses – ANZAC and Empire, Canberra 1995, p. 187.

- ↑ Cathcart, Defending the National Tuckshop 1988; Moore, Andrew: The Secret Army and the Premier: Conservative Paramilitary Organisations in New South Wales 1930-32, Kensington 1989.

- ↑ Amos, Keith: The New Guard Movement 1931-1935. Carlton 1976.

- ↑ Lake, Marilyn: The Limits of Hope: Soldier Settlement in Victoria 1915-38, Melbourne 1987.

- ↑ For an overview, see Garton and Stanley, The Great War and its Aftermath 2013, pp. 60-61 and Bongiorno, Frank: Search for a Solution, 1923-39, in: Bashford and Macintyre (eds.), Cambridge History of Australia 2013, p. 66. See also Scates, Bruce and Oppenheimer, Melanie: “I Intend to Get Justice”: The Moral Economy of Soldier Settlement, in Bongiorno, Frank/Frances, Raelene/Scates, Bruce (eds.): Labour and the Great War: The Australian Working Class and the Making of Anzac, in: Labour History 106 (2014), pp. 229-53.

- ↑ Gammage, Bill: The Broken Years: Australian Soldiers in the Great War, Canberra 1974; Roe, Jill: Left Behind?, 1915-39, in Roe, Jill (ed.): Social Policy in Australia: Some Perspectives, 1901-1975, Sydney 1976, pp. 101-12; Garton and Stanley, The Great War and its Aftermath 2013, p. 59.

- ↑ Williams, John F.: The Quarantined Culture: Australian Reactions to Modernism, 1913-1939, Cambridge 1995.

- ↑ Bongiorno, Sex Lives 2012, pp. 162-5.

Selected Bibliography

- Amos, Keith: The New Guard movement, 1931-1935, Melbourne 1976: Melbourne University Press.

- Bollard, Robert: In the shadow of Gallipoli. The hidden history of Australia in World War I, Sydney 2013: NewSouth Publishing.

- Cathcart, Michael: Defending the national tuckshop. The secret army intrigue of 1931, Fitzroy 1988: McPhee Gribble; Penguin.

- Crotty, Martin: The Returned Sailors’ and Soldiers’ Imperial League of Australia 1916-46, in: Crotty, Martin / Larsson, Marina (eds.): Anzac legacies. Australians and the aftermath of war, Melbourne 2010: Australian Scholarly Publishing, pp. 166-186.

- Damousi, Joy: The labour of loss. Mourning, memory, and wartime bereavement in Australia, Cambridge; New York 1999: Cambridge University Press.

- Evans, Raymond: The red flag riots. A study of intolerance, St. Lucia; New York 1988: University of Queensland Press.

- Garis, Brian K. de: An incident at Fremantle, in: Labour History 10, 1966, pp. 32-37.

- Garton, Stephen: The cost of war. Australians return, Melbourne; New York 1996: Oxford University Press.

- Garton, Stephen / Stanley, Peter: The Great War and its aftermath, 1914-22, in: Bashford, Alison / Macintyre, Stuart (eds.): The Cambridge history of Australia. The Commonwealth of Australia, volume 2, Cambridge 2013: Cambridge University Press, pp. 39-63.

- Inglis, Kenneth Stanley / Brazier, Jan: Sacred places. War memorials in the Australian landscape, Carlton 1998: Melbourne University Press.

- Inglis, K. S.; Phillips, Jock: War memorials in Australia and New Zealand. A comparative survey, in: Australian Historical Studies 24/96, 1991, pp. 179-191.

- King, Terry: The tarring and feathering of J. K. McDougall. 'Dirty tricks' in the 1919 federal election, in: Labour History 45, 1983, pp. 54-67.

- Lake, Marilyn: The limits of hope. Soldier settlement in Victoria, 1915-38, Melbourne; New York 1987: Oxford University Press.

- Larsson, Marina: Shattered Anzacs. Living with the scars of war, Sydney 2009: University of New South Wales Press.

- Luckins, Tanja: The gates of memory. Australian people's experiences and memories of loss and the Great War, Freemantle 2004: Curtin University Books.

- McLachlan, Noel: Nationalism and the divisive digger. Three comments, in: Meanjin Quarterly 27/3, 1968, pp. 302-308.

- Moore, Andrew: The secret army and the premier. Conservative paramilitary organisations in New South Wales, 1930-32, Kensington 1989: New South Wales University Press.

- Scates, Scates; Oppenheimer, Melanie: 'I intend to get justice'. The moral economy of soldier settlement, in: Labour History 106/1, 2014, pp. 229-253.

- Smith, F. B.: If Australia had not participated in the Great War? An essay on the costs of war, in: Wilcox, Craig / Aldridge, Janice (eds.): The Great War, gains and losses. Anzac and empire, Canberra 1995: Australian War Memorial; Australian National University, pp. 179-195.

- Williams, John F.: The quarantined culture. Australian reactions to modernism, 1913-1939, New York 1995: Cambridge University Press.