Britain’s Economic Transformation during the First World War↑

It is easy to view Britain’s entry into the First World War as part of a moral obligation (established under the Treaty of London of 1839) to guarantee Belgium’s neutrality in the face of German aggression. The simplicity of this interpretation becomes apparent once we appreciate the complexity of international political/economic relations – especially those concerning Britain and Germany – that had developed during the early 20th century, and which came to the fore in the summer of 1914. Britain’s decision to intervene in the European conflict in August 1914, drawing in the might of the British Empire by extension, was driven by concerns over her national political/economic security arising from the fear that Europe could, in the aftermath of war between the great powers, fall under German hegemony.

The initial policy response of the British government – captured by the phrase “business as usual”, and signifying a belief in the limited need for state organisation to support the war effort – reflected the view that the conflict would have no significant impact on Britain’s economic or social structures. This policy response did not reflect any significant adherence to the liberal philosophy of laissez-faire, but rather the implementation of military/economic calculations concerning existing maritime strength that had been developed before August 1914. Put simply, pre-war military strategy centred around belief in the power of the Royal Navy’s Dreadnoughts to protect the nation from invasion and defeat Germany through blockade.[1]

Such pre-war calculations vanished in the early months of the conflict due to several interconnected factors: (1) the rush of enlistment generated labour shortages in many sectors of the economy,[2] (2) the emergence of trench warfare coupled with the growing need for heavy artillery and high explosive shells, and (3) the limited ability of British munitions firms to fulfil the massive demands of an expanding army engaged in static (trench) warfare. By the spring of 1915, growing public criticism of the shortage of munitions for front line troops led to the creation of the Ministry of Munitions under the dynamic leadership of David Lloyd George (1863-1945).[3]

Initial war-time controls concerning troop transport and requisitioning had been governed by the Regulation of the Forces Act (1871) and, most famously, the Defence of the Realm Act (1914). Yet it was the industrial and administrative machinery of the Ministry of Munitions and, later, the Ministry of Food (1916) that enabled the British state to directly control the production, consumption, and distribution of goods and materials necessary for the prosecution of the war. Such forms of state intervention were forged through brutal urgency, and their impact was felt in all areas of society, including the distribution and regulation of civilian labour (securing an adequate division of manpower between the armed forced and industry was a key aspect of state activity during the war), shipping, rail and canal transport, the building of national factories for armament production, and the consumption of all major foods through rationing and price controls.

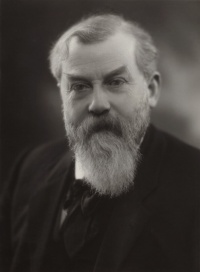

Britain’s war-time economic system reached its zenith in the autumn of 1918. Less than three years later, this elaborate system of state controls had vanished. In a famous article published in 1943, Richard Tawney (1880-1962) argued that this sudden change had been due to the failure of the war-time government to survey the post-war situation, thereby allowing businessmen, bankers and Treasury officials to push for the speedy return of pre-war economic orthodoxy.[4] This interpretation was revised nearly 40 years later by Peter Cline, who argued that the removal of Britain’s war-time controls should be interpreted as a reflection of changing war-time expectations regarding the post-war position/strength of both Britain and Germany. The central feature of Cline’s argument is that war-time expectations of Britain’s post-war economic defence needs were based around the perceived threat of an economically powerful post-war Germany. This initially led war-time planners to push for the continuation of economic controls once the war ended. It was only Germany’s sudden collapse towards the end of 1918 that destroyed these expectations, and hence all political justifications for the continuation of Britain’s war-time economic system.[5]

The Political Economy of British War Finance and Post-War National Debt↑

A comparison of the British and German methods of war finance highlights two important points – (1) the key similarity between the two countries was the heavy reliance on war loans rather than taxation, and (2) the key difference between the two countries was the different modes of financing these deficits. Focusing on point (2), Theo Balderston has shown how these different modes of war finance reflected the different capacities of the London and Berlin capital markets – there was a clear willingness in Britain to accept British treasury bills (seen as suitable, safe, short-term investments), while the same degree of willingness to accept German government debt did not exist in Germany. The resources of the City of London therefore served as a powerful shock absorber that allowed Britain to deal with the immediate financial issues of “total war”.[6]

War-time debates over national finance centred around the feasibility and probable consequences of employing either loans or increased taxation to meet the enormous expense of prosecuting the war. Approximately 25 percent of war-time expenditure was met out of current revenue,[7] with the government’s main needs covered by three loans – £350m (1914), £900m (1915), and £2,127m (1917) – and, from April 1915, short-term borrowing secured through the sale of medium-term bonds and an increased supply of Treasury bills.[8] The expensive and inefficient character of Britain’s wartime financial policy generated an unfavourable legacy in the form of a huge, parasitic national debt.[9] For the financial year 1913/14, Britain’s national debt stood at £706m, with debt equal to roughly 26 percent of GDP. By 1918/1919, the respective figures had risen to £7,481m and nearly 128 percent.[10] In the face of such dislocated public finances, fiscal stabilisation in the 1920s became a complex operation that revolved around the degree of public consent within the tax system. These problems reflected the wider post-war political and social context (most notably rising labour unrest in the 1920s), and the political requirement that no single interest group should suffer undue hardship or receive preferential treatment in efforts to tackle the debt burden. Although seeking to reassert the broad legitimacy of the tax system, post-war British governments possessed little room for manoeuvre – war-time promises constrained the ability of post-war governments to increase taxation on the working-classes (any increases in direct or indirect taxation that impacted working-class expenditure had the potential to intensify early post-war social conflict); industry repeatedly complained about the post-war fiscal burden it was forced to carry; and the middle-class opposed government ‘waste’ and demanded reductions in public expenditure associated with education and housing policies.[11]

The government’s eventual means of navigating these demands involved three approaches: (1) the fragmentation of opposition amongst working-class income-tax payers through the use of allowances granted to wives and children,[12] (2) the continuation of direct taxation on industry that removed the risk of reaction from both the working-class and the middle-class, and (3) the so-called “Geddes Axe”, associated with the 1921-22 Committee on National Expenditure, chaired by Sir Eric Geddes (1875-1937), that proposed reductions in all aspects of government expenditure (particularly in the areas of post-war social expenditure). This tackled criticism from middle-class voters while allowing the government to pass on some of the costs of the war to the working classes.[13] By the mid-1920s, the contentious nature of post-war taxation had largely been neutralised.

Ireland: War Economy, Revolution and Independence, 1914-1922↑

Much of the recent historiography on Ireland during the First World War has focused on Irish recruitment into the British army, the wartime experiences of Irishmen in the British army, and the character of commemoration and memorialisation.[14] Yet the economic dimension of the war should not be forgotten, and during the years 1914 and 1920, Ireland (which, until 1922, was still part of the United Kingdom) experienced a period of unprecedented prosperity. This prosperity was primarily a consequence of war-time stimulus to key sectors of the Irish economy, including agriculture, textiles, and shipbuilding.[15] Contracts from the Ministry of Munitions supported the textile industries (particularly the demand for linen) and general engineering firms, while the two largest shipbuilding firms – Harland and Wolff and Workman and Clark & Co. – employed over 25,000 dockers building merchant and navy ships.[16] The rural economy benefited significantly from the demands of the war economy, with the value of agricultural produce doubling between 1913 and 1918 and farm labour wages increasing by over 60 percent.[17]

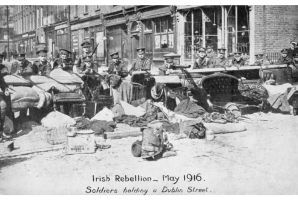

The First World War played a significant role in the course of Ireland’s political history. The outbreak of hostilities in 1914 suspended existing proposals for Irish home rule, and diffused simmering tensions and the immediate prospect of civil war amongst unionists and nationalists. Yet there is no denying that the war was a catalyst for political revolution. The 1916 Easter rebellion in Dublin 1916[18] and the success of Sinn Féin at the December 1918 election, followed by failed attempts to reach a political settlement, led to armed conflict and the Irish War of Independence (1919-1921).[19] By the early 1920s, it was clear that Britain could no longer deny Irish self-government. The Government of Ireland Act (1920) and the Anglo-Irish Treaty (1921) ended British rule in 26 Irish counties, but gave power to the six counties of Northern Ireland to opt out of the new arrangements. The eventual result was the partition of Ireland and the creation of the Irish Free State in December 1922.[20]

Industrial Disputes, 1919-1926↑

It was certainly hoped during the war that Britain’s post-war economic remobilisation would be secured through improved relations between capital and labour.[21] However, the years from 1919 to 1926 were the most contentious in British industrial history: increased war-time union membership, coupled with a desire to assert a new-found sense of confidence and strength, meant that the early post-war period was characterised by union and working-class militancy.

The early 1920s witnessed three instances of actual or attempted collective industrial action which had significant political/economic implications. These were: (1) the abortive threat of industrial action by the trade unions in April 1921 (the so-called “Black Friday” for the union movement), (2) the successful threat of action by the unions in July 1925, and the resulting capitulation of the government (leading to the so-called “Red Friday” for the unions which blocked out the memory of April 1921), and (3) the collapse of negotiations between the government and the unions over wages, working hours, and subsidies for the mining industry, leading to the general strike of May 1926.

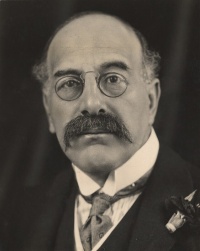

The history of the general strike draws out a number of important issues. First, the strike demonstrated the determination of organised labour to fight wage cuts. Second, the eventual termination of the strike by the Trades Union Congress (TUC) after nine days marked a sudden and dramatic defeat for the miners. The miners soldiered on alone until November 1926 at which point they were forced to accept a wage-setting at lower rates. Having previously occupying a key position in the post-war union movement, the miners became a relatively insignificant force for the remainder of the inter-war period. Third, and following from this, the miners’ defeat left its mark on the wider union movement, and the events of 1926, although far from being a major turning point in British trade union history, serve as a clear point separating a period of post-war industrial conflict from one of relative industrial peace that existed for the remainder of the inter-war period.[22] One indirect outcome of the strike was the Mond-Turner talks of 1927-1928. These talks – between Sir Alfred Mond (1868-1930), a Conservative MP and prominent industrialist, and Ben Turner (1863-1942), President of the TUC – were aimed at industrial co-operation at the national level, and the reconciliation of the two sides of industry in matters of rationalisation and wages. Although little came from these talks, they were symbolic of a new attitude of compromise and brought all sides (employers, labour, and the government) out of the confrontational stances that had typified much of the early 1920s.[23] Finally, actions by the British government aimed at stamping out displays of political activism throughout much of 1926, reflected in the unjust application of laws by ministers, magistrates, and the police purporting to act under the authority of Parliament, raises often unexplored questions about the integrity of constitutional practice and the nature of civil liberties in inter-war Britain.[24]

The Dark Shadow of Unemployment↑

In May 1920, less than one percent of the insured labour force was registered as unemployed; by May 1921, that figure had risen to 23 percent.[25] During these twelve months, the British economy experienced a severe contraction leading to the appearance of heavy and continuous unemployment. Unemployment was, without question, the defining characteristic of inter-war Britain. At its simplest, Britain’s post-war economic malaise reflected permanent changes in the international environment. First, post-war confidence in the international economy was undermined by the redrawing of political boundaries and the rapid alteration of tariff levels. Second, wider structural changes within the international economy reflected changing patterns of demand for British exports (e.g. away from coal and towards oil). Finally, it is important to note the permanent destruction of once secure pre-war trading relationships as foreign competitors undercut British producers in exports markets (e.g. the rise of Japanese cotton production), and the loss of markets for British cotton goods in the Far East. As the old sectors of Britain’s industrial structure shed labour, the resulting unemployment problem fell very unevenly across different industries and regions.[26]

The extent of inter-war unemployment has led commentators (both inter-war writers and historians) to ask whether the provision of Britain’s financial relief – the “dole” – actually contributed to the evil it was intended to remedy. For the vast majority of inter-war commentators, any suggestion that there existed a large body of idle, thriftless individuals, prepared to abuse the unemployment insurance scheme rather than seek gainful employment, was dismissed as palpable nonsense. The suggestion that money benefits acted as an opiate to relax individual effort were dismissed by the economist Edwin Cannan (1861-1935) as nothing short of insanity.[27] The possibility that man could, though habit, become accustomed to the benefits, was also dismissed on the grounds that natural pride would always dictate a preference for employment over charity. In this sense, argued John Harry Jones (1881-1973), the suggestion that state assistance had contributed to a situation of deliberate unemployment was dismissed according to a philosophical impression of the natural, unblemished character of labour.[28]

This is not to suggest that all contemporary commentators accepted this interpretation. An inherent belief in the unblemished character of the labour force did not find favour with Harold Cox (1859-1936) who argued that the universality of a public benefits system had distorted the hard-working and fair-minded characteristics of the labour force. In other words, men who had once been proud of their independence had gradually succumbed to the temptation of the dole.[29] This interpretation was revived in the 1970s in a controversial article by Benjamin and Kochin, who argued that unemployment benefits had provided an alternative to wages, thereby leading to a high level of voluntary unemployment.[30] It must be stressed that few historians accept this view, arguing that there is no evidence that unemployment benefits retarded the effort of the unemployed to find work.[31]

The Return to the Gold Standard↑

The gold standard had been part and parcel of the increasing integration of the global economy during the nineteenth century, assisting both international trade and international lending. From Britain’s perspective, the principles of this fixed exchange rate system had been undermined during the war through inflation, severe budgetary imbalances, and the enormous insurance costs of transporting gold across the Atlantic. From the autumn of 1915 through the spring of 1919, the sterling-dollar exchange had been artificially maintained (“pegged”) at $4.765, fractionally below the pre-war level of $4.86, through the assistance of American lending. Once this artificial support was terminated in March 1919, the value of sterling fell on the exchanges. In order to prevent a catastrophic loss of gold to export, the British government issued a temporary gold embargo order that brought sterling off the gold standard. Such a suspension of the gold standard was not new (a similar measure had operated between 1797 and 1819 due to the Napoleonic Wars), and it in no way undermined Britain’s commitment to the gold standard: the government had already signalled a return to gold at the pre-war parity as a key goal of Britain’s post-war financial policy, and the 1919 gold embargo is easily interpreted as a tactical withdrawal in the face of enormous financial difficulties. The ultimate goal of restoring the gold standard was never abandoned, a fact that is apparent once we appreciate that the embargo was later regularised as the Gold Embargo Act (1920), a piece of time-limited legislation that would automatically return Britain to the gold standard once it expired at the end of December 1925.

When Winston Churchill (1874-1965) became Chancellor of the Exchequer in November 1924, the general expectation was that the British government would shortly complete sterling’s return to the gold standard at the pre-war parity ($4.86). Churchill’s initial support for Britain’s speedy return to gold was, however, tempered by the comments of the economist, John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946). Keynes’s critique of British policy centred around the social and political difficulties of securing Britain’s return to gold at the pre-war rate. Taking the sterling-dollar exchange as a ratio of British and US prices, Keynes’s argument focused on the necessary movement of sterling towards the $4.86 rate that committed Britain to a reduction in the money costs of production. It would have been impossible, he argued, to secure such a change in the international value of sterling given political issues (the post-war climate of industrial unrest in Britain) and economic issues (the “stickiness” of money-wages). Instead of seeking to adjust the domestic cost of production to meet a set international value for sterling (i.e. $4.86), it would be better to accept social/political circumstances and so adjust the international value of sterling to the domestic costs of production. Based on a comparison of British and US price indices, Keynes argued that the rate of exchange at which Britain should return to the gold standard was $4.40, meaning that at the pre-war parity, sterling would be overvalued by around 10 percent. Although impressed by Keynes’s argument, Churchill accepted case put forward by Treasury and Bank of England officials. In late March 1925, Churchill lifted the gold embargo in his budget speech and Britain returned to the gold standard at the pre-war parity.[32]

Keynes interpreted the policy as a blunder on the part of Churchill’s Treasury officials who, through their ignorance, had failed to fully grasp key issues concerning the disequilibrium between British and American prices and hence the difficulties associated with restoring the pre-war parity between sterling and the dollar. Within the context of the political economy of the gold standard, this interpretation suggests that a different policy decision would have been reached if Churchill’s experts had fully understood the economic problem they faced. However, a different story emerges once we consider the return to gold in 1925 in relation to vested interests rather than economic theory. Two interesting examples of this approach can be found in the work of Pollard and Tomlinson. Pollard stressed the role of the Bank of England, in particular the Court of Governors, who pushed for Britain’s return to gold at $4.86 in the interests of the City of London. Following a similar line of argument, Tomlinson focused on the internal interests of the Bank of England, arguing that the bank’s push to return Britain to gold in 1925 reflected its desire to regain control over short-term rates in the London money markets.[33]

Following Keynes’s critique, adherence to the principles of the gold standard at an overvalued rate priced British goods out of world markets, thereby necessitating high interest rates that inhibited business investment and exacerbating the country’s post-war unemployment problem.[34] This raises the obvious question of whether a lower sterling-dollar exchange (accepting, say, Keynes’s figure of $4.40 instead of $4.86) would have alleviated Britain’s problem of unemployment in the late 1920s. In theory, a lower rate of exchange would have helped exports, inhibited imports, and reduced interest rates. Set against the historical record, it is difficult to support the view that a lower rate of exchange would have helped British industry resolve its difficulties. While a lower rate of exchange would have helped, the general historical consensus is that this would not have solved the underlying structural changes facing British producers.[35]

Christopher Godden, University of Manchester

Section Editor: Adrian Gregory

Notes

- ↑ French, David: British Economic and Strategic Planning, 1905 – 1915. London 1982; French, David: The Rise and Fall of Business as Usual, in: Burk, Kathleen (ed.): War and the State. The Transformation of British Government, 1914–1919, London 1982, pp. 7-31; Lambert, Nicholas A.: Planning Armageddon. British Economic Warfare and the First World War, Cambridge, Massachusetts 2012, pp. 19-181; McDermott, John: Total War and the Merchant State. Aspects of British Economic Warfare against Germany, 1914 – 1916, in: Annales Canadiennes d’Histoire 21 (1986), pp. 61-76.

- ↑ Dewey, Peter: Military Recruitment and the British Labour Force during the First World War, in: Historical Journal 27 (1984), pp. 199-223.

- ↑ Fraser, Peter: The British Shells Scandal of 1915, in: Annales Canadiennes d’Histoire 18 (1983), pp. 77-94; French, David: The Military Background to the Shell Crisis of May 1915, in: Journal of Strategic Studies 2 (1979), pp 192-205; Adams, R.J.Q.: Arms and the Wizard. Lloyd George and the Ministry of Munitions, 1915–1916, London 1978; Grieves, Keith: Lloyd George and the Management of the British War Economy, in: Chickering, Roger / Förster, Stig (eds.): Great War, Total War. Combat and Mobilization on the Western Front, 1914-1918, Cambridge 2000, pp. 369-388; Wrigley, Chris: The Ministry of Munitions. An Innovative Department, in: Burk, War and the State 1982, pp. 32-56.

- ↑ Tawney, Richard: The Abolition of Economic Controls, 1918-1921, in: Economic History Review 13 (1943), pp. 1-30.

- ↑ Cline, Peter: Winding Down the War Economy. British Plans for Peace-Time Recovery, 1916–1919, in: Burk, War and the State 1982, pp. 157-181.

- ↑ Balderston, Theo: War Finance and Inflation in Britain and Germany, 1914-1918, in: Economic History Review 42 (1989), pp. 222-244.

- ↑ Balderston, War Finance 1989, p. 226.

- ↑ Morgan, E.V.: Studies in British Financial Policy, 1914–1925. London 1952, pp. 106-112.

- ↑ Daunton, Martin: Just Taxes. The Politics of Taxation in Britain, 1914–1979, Cambridge 2002, pp. 36-59.

- ↑ Broadberry, Stephen / Howlett, Peter: The United Kingdom during World War I. Business as Usual?, in: Broadberry, Stephen / Harrison, Mark (eds.): The Economics of World War I. Cambridge 2005, p. 219. Years are fiscal years (i.e. 1913/14 is 1 April 1913 to 31 March 1914).

- ↑ Daunton, Martin: How to Pay for the War. State, Society and Taxation in Britain, 1917-1924, in: English Historical Review 111 (1996), pp. 882-919; Daunton, Just Taxes 2002, pp. 60-102.

- ↑ Whiting, R.C.: Taxation and the Working Class, 1915 - 24, in: Historical Journal 33 (1990), pp. 895-916.

- ↑ McDonald, Andrew. The Geddes Committee and the Formulation of Public Expenditure Policy, 1921-1922, in: The Historical Journal 32 (1989), pp. 643-674.

- ↑ Callan, Patrick: Recruiting for the British army in Ireland during the First World War, in: Irish Sword 17 (1987), pp. 42 – 56; Pennell, Catriona: Going to War, in: Horne, John (ed.): Our War. Ireland and the Great War, Dublin 2008, pp. 37-48; Bowman, Timothy: Irish Regiments in the Great War: Discipline and Morale, Manchester 2003; Jeffery, Keith: Ireland and the Great War. Cambridge 2000.

- ↑ Johnson, David: The Inter-War Economy in Ireland. Dundalk 1985, pp. 3-5.

- ↑ McCann, Gerard: Ireland’s Economic History. Crisis and Development in the North and South, London 2011, pp. 60-62.

- ↑ Keith, Ireland and the Great War 2000, pp. 30-31.

- ↑ McNally, Michael / Dennis, Peter: Easter Rising 1916. Birth of the Irish Republic, Dublin 2007; McGarry, Fearghal: The Rising. Ireland, Easter 1916. Oxford 2010.

- ↑ Dolan, Anne: The British Culture of Paramilitary Violence in the Irish War of Independence, in: Gerwarth, Robert and Horne, John (eds.): War in Peace. Paramilitary Violence in Europe after the Great War, Oxford 2012, pp. 200-215.

- ↑ Harkness, D.W.: The Restless Dominion: The Irish Free State and the British Commonwealth of Nations, 1921–1931, London 1969.

- ↑ See, for example, Chapman, Sydney: The State and Labour, in: Dawson, William Harbutt (ed.): After-War Problems. London, pp. 123-136.

- ↑ Laybourn, Keith: The General Strike of 1926. Manchester 1993, pp. 100-117.

- ↑ McDonald, G.W. / Gospel, Howard F.: The Mond Turner Talks, 1927 – 1933. A Study in Industrial Co Operation, in: Historical Journal 16 (1973), pp. 807-829.

- ↑ Gearty, Conor / Ewing, Keith: The Struggle for Civil Liberties. Political Freedom and the Rule of Law in Britain, 1914-1945, Oxford 2001, pp. 155-213.

- ↑ Flanagan, Richard: Parish-Fed Bastards. A History of the Politics of the Unemployed in Britain, 1884–1939, London 1991, p. 118.

- ↑ Solomou, Solomos: Themes in Macroeconomic History. The UK Economy, 1919–1939, Cambridge 1996, pp. 53-84; Hatton, Tim: Unemployment and the labour market in inter-war Britain, in: Floud, Roderick / McCloskey, Donald (eds.): The Economic History of Britain since 1700. Volume 2, 1860 – 1939, Cambridge 1994, pp. 359-385. See also Clay, Henry: The Post-War Unemployment Problem. London 1929.

- ↑ Cannan, Edwin: The Post-War Unemployment Problem, in: Economic Journal 40 (1930), p. 46.

- ↑ Jones, John Harry: Remedies for Unemployment, in: The Accountant 73 (1925), p. 85; Beveridge, William: Social Malingering, in: The Listener 5 (1931), p. 1014.

- ↑ See Cox, Harold: The Public Purse, in: Edinburgh Review 234 (July 1921), pp. 192-194; Cox, Harold: Franchise Reform, in: Edinburgh Review 246 (July 1927), p. 197.

- ↑ Benjamin, Daniel K. / Kochi, Levis A.: Searching for an Explanation of Unemployment in Inter-war Britain, in: Journal of Political Economy 87 (1979), pp. 441-478.

- ↑ Collins, Michael: Unemployment in Interwar Britain. Still Searching for an Explanation, in: Journal of Political Economy 90 (1982), pp. 369-379; Cross, Rodney: How Much Voluntary Unemployment in Interwar Britain? in: Journal of Political Economy 90 (1982), pp. 380-385; Metcalf, David et al.: Still Searching for an Explanation of Unemployment in Interwar Britain, in: Journal of Political Economy 90 (1982), pp. 386-399.

- ↑ Moggridge, Donald E.: British Monetary Policy 1924–1931. The Norman Conquest of $4.86, Cambridge 1972.

- ↑ Pollard, Sydney: The Gold Standard and Employment Policies between the Wars. London 1970, pp.1-26; Tomlinson, Jim: Problems of British Economic Policy, 1870–1945. London 1981, pp. 92-105.

- ↑ Jones, M.E.F.: The Regional Impact of the Overvalued Pound in the 1920s, in: Economic History Review 38 (1985), pp. 393-401.

- ↑ Wolcott, Susan: Keynes versus Churchill. Revaluation and British Unemployment in the 1920s', in: Journal of Economic History 53 (1993), pp. 601-628.

Selected Bibliography

- Boyce, Robert W. D.: British capitalism at the crossroads, 1919-1932. A study in politics, economics, and international relations, Cambridge 1988: Cambridge University Press.

- Broadberry, Stephen N. / Howlett, Peter: The United Kingdom during World War I. Business as usual?, in: Broadberry, Stephen N. / Harrison, Mark (eds.): The economics of World War I, Cambridge; New York 2005: Cambridge University Press, pp. 206-234.

- Cline, Peter: Winding down the war economy. British plans for peace-time recovery, 1916-1919, in: Burk, Kathleen (ed.): War and the state. The transformation of British government, 1914-1919, London; Boston 1982: Allen & Unwin, pp. 157-181.

- Daunton, Martin J.: How to pay for the war. State, society and taxation in Britain, 1917-24, in: The English Historical Review 111/443, 1996, pp. 882-919.

- French, David: British economic and strategic planning, 1905-1915, London; Boston 1982: Allen & Unwin.

- Hatton, Tim: Unemployment and the labour market in inter-war Britain, in: Floud, Roderick / McCloskey, Donald N. (eds.): The economic history of Britain since 1700, 1860-1939, volume 2 (2 ed.), Cambridge 1994: Cambridge University Press, pp. 359-385.

- Johnson, David: The interwar economy in Ireland, Dundalk 1985: Dundalgan Press.

- Laybourn, Keith: The general strike of 1926, Manchester; New York 1993: Manchester University Press.

- Lloyd-Jones, Roger / Lewis, Myrddin John: Arming the Western Front. War, business and the state in Britain 1900-1920, London; New York 2016: Routledge; Taylor & Francis Group.

- Moggridge, Donald E.: British monetary policy, 1924-1931. The Norman conquest of $4.86, Cambridge 1972: Cambridge University Press.

- Solomou, Solomos: Themes in macroeconomic history. The UK economy, 1919-1939, Cambridge 1996: Cambridge University Press.

- Whelejan, Niall: The Irish Revolution, 1912-23, in: Jackson, Alvin (ed.): The Oxford handbook of modern Irish history, Oxford 2017: Oxford University Press, pp. 621-644.

- Williamson, Philip: National crisis and national government. British politics, the economy and empire, 1926-1932, Cambridge 1992: Cambridge University Press.