Early Career↑

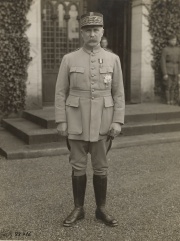

Philippe Pétain (1856-1951) was born into a family of farmers in northern France. He was well educated, thanks to an uncle, who was a priest, and was accepted in 1876 to St-Cyr, the French officers’ academy. In 1888, he graduated from the the École Supérieure de Guerre (ESG), the French staff college. At the turn of the 20th century, Pétain was a confirmed bachelor and was known as a cold, yet well-rated officer. He held strong views and was noticed in Paris as a shooting instructor at the ranges of the Chalon School.

Between 1901 and 1911, he taught “applied tactics” at the ESG and was soon considered a maverick since he focused on firepower during a period when “Offensive à outrance” (“offensive to excess”) doctrine in the French army (and beyond) was popular. His commission to the rank of colonel in 1910 was late. By 1914 he was fifty-eight and close to retirement.

The War↑

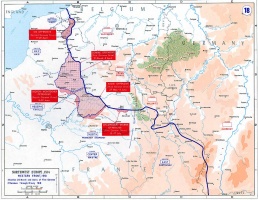

When the war broke out, Colonel Pétain was acting commander of a brigade in the 2nd army corps (General Charles Lanrezac (1852-1925)) in the left wing of the French army.

The Cold-blooded Technician (1914-1915)↑

He was promoted to Général de Brigade at the end of August 1914 and, after his participation in September in the Battle of the Marne, to Général de Division. During the Artois offensives, he successfully led the 33rd army corps; in June 1915 he commanded the 2nd army.

Pétain soon understood that the army had entered a long and protracted siege war, which required adapted weaponry, ammunition in abundance, and life-saving tactics. He also distanced himself from the mantra of gaining ground at all cost, arguing that defensive actions and “limited goal attacks” had to be combined and constantly improved.

The Battle of Verdun (1916)↑

When the Germans launched a full-scale offensive on Verdun on 21 February 1916, Pétain was ordered by General Joseph Joffre (1852-1931) to defend the fortified region at the head of the 2nd army. He obtained artillery and planes and showed his mastery in frontline design, logistics, and resource management. He was trusted by his soldiers, which was a decisive factor in allowing him to stabilize the situation. He left the battle theatre in the first days of May 1916 to take command of the Groupe d’Armée du Centre (GAC). The memory of his action in this critical moment of the war has not been forgotten.

General-in-Chief (1917-1918)↑

Appointed general-in-chief on 15 May 1917, Pétain appeared to the troops as a capable commander, who knew well what life was like in the trenches. This knowledge helped him counter the wave of serious mutinies that swept the ranks of the French army in spring 1917. Pétain pragmatically paid attention to the tactical and organizational claims of soldiers before any political interpretation. Offensives were put on hold, and the leave system and rear front layout were improved. Of the nearly 3,000 soldiers sentenced by the conseils de guerre, 554 were sentenced to death (10 percent of them were executed). The troubles were over by mid-June. At that time, Pétain carried out an active reorganization of the frontline: rational and deep fortification, heavier air, artillery and tank support, and thorough preparation for attacks.

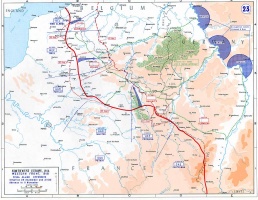

The Germans launched their Spring Offensives in March 1918. Pushed back to the Marne and in a critical position, the French army resisted with its allies, adopting a more materiel based profile. At the time of the victory offensives, in October 1918, Pétain failed to obtain a last offensive beyond the Rhine before the armistice from Ferdinand Foch (1851-1929). On 19 November, Pétain paraded in Metz and was elevated to the distinction Maréchal de France.

Post-war: From Verdun to Vichy, One-way↑

Philippe Pétain’s story during the First World War is undoubtedly a success story. In France at the end of 1918, he stood as one of the most popular generals alongside Foch. The “victor of Verdun“ remained commander-in-chief until 1931. War minister in 1934, his longevity allowed him to decisively shape the French army in the inter-war period. Indeed, twenty years after the victory, the French army prepared for a protracted conflict, mired in materiel-based defensive-offensive strategy and tactics.

This stance and German boldness, among other things, led France to military rout in May 1940. Amid the turmoil, Pétain made the most of his image as the pragmatic and fair “victor of Verdun”, presenting himself as the last resort for negotiating an armistice with Nazi Germany. After he was given full powers by the French parliament in July, and his famous handshake with Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) in October, he became the man of Vichy, the capital city of the French state (État Français), a reactionary and collaborationist regime that toppled the Third Republic. Vichy would integrate with Nazi Europe, fighting its enemies, implementing the plundering of the country, and endorsing antisemitic policies.

In 1945, Maréchal Pétain was brought to trial. Sentenced to death for high treason and condemned to national indignity, all his titles were revoked. Now simply Philippe Pétain, he was exiled to the remote Île d’Yeu by one of his former staff officers, Charles de Gaulle (1890-1970), who had been the head of Free France during the war.

Whether he was a traitor or a “shield” for a defeated France would divide the French for decades, especially those who lived through the war. A century after the victory of 1918, Pétain is still a sensitive topic in French memory. His remains stay banished on a far western island and are perceived as the keystone of a dark period in French history, discarded by the Republic that never fulfilled his wish to rest in the Douaumont ossuary amongst the soldiers who fell at Verdun.

Olivier Cosson, Independant Scholar

Section Editor: Emmanuelle Cronier

Selected Bibliography

- Ferro, Marc: Pétain, Paris 1987: Fayard.

- Lottman, Herbert R.: Pétain, Paris 1984: Seuil.

- Pedroncini, Guy: Pétain. Le soldat et la gloire 1856-1918, Paris 1989: Perrin.

- Pétain, Philippe / Delmas, Jean (ed.): Cours d'infanterie enseigné à l'École supérieure de guerre (1911), Lyon 2010: Éd. du Cosmogone

- Prost, Antoine / Krumeich, Gerd (eds.): Verdun, 1916. Une histoire franco-allemande de la bataille, Paris 2015: Tallandier.