Pershing’s Education and Early Career↑

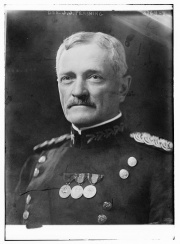

John J. Pershing (1860-1948), born and schooled in rural Missouri, graduated from the United States Military Academy during the summer of 1886. Instructors and administrators at the Academy widely commented upon his leadership qualities and attention to detail, promoting him to First Captain, the Academy’s highest cadet rank, his senior year. From such an auspicious start, Pershing’s career seemed to fade into the obscurity that dogged the American post-Civil War army. Entering service during the mid-1880s, Pershing missed most of the Indian Wars that had dominated the previous decade. The U.S. Army labored under an antiquated promotion system that allowed junior officers to languish over a decade between promotions. Pershing served with distinction but without fanfare, helping police the gradually calming western frontier. Most notably during this period, Pershing commanded troops of Indian Scouts and “Buffalo Soldiers,” African-American cavalry troopers. Many considered both of these assignments as career-enders, and upon his return to West Point as an instructor in 1897, the cadets derisively referred to him as “Black Jack.”

Pershing’s career began its meteoric rise upon the onset of the Spanish-American War. Leaving West Point, Pershing returned to the Buffalo Soldiers of the 10th Cavalry Regiment and served with gallantry throughout the conflict. Pershing then requested an assignment in the Philippines, arriving during the spring of 1899 amidst the chaotic events of the Philippine Insurrection. He worked deep in the jungles of Mindanao and Jolo, building trust with local Moro tribesmen in order to win them over to the Americans’ side. His successes in the Philippines brought him to the attention of President Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919), who, seeking a good news story from the growing quagmire of the Philippines, sought Pershing’s promotion and publicity for his achievements. In 1905, Roosevelt selected Pershing for brigadier general, skipping three ranks and leap-frogging 835 more senior officers. This initiated rumblings of political machinations that dogged Pershing throughout his career.

Simmering tensions along the Mexican-American border, brought to a boil by the events of the Mexican Revolution, exploded on 9 March 1916 when Mexican revolutionary Francisco Villa (1878-1923) attacked Columbus, New Mexico. Less than a week later, President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) ordered Pershing, now in command along the border after returning from the Philippines, to attack into Mexico and capture Villa and his men. The Punitive Expedition achieved few material gains and never captured Villa. Pershing learned numerous lessons, however, particularly concerning the necessity of stable logistics and thorough staff preparation. More importantly, he gained the confidence of Wilson, and when war broke out between the United States and the Central Powers on 6 April 1917 he handpicked Pershing to lead the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) in France.

Commander-in-Chief, American Expeditionary Force↑

Pershing, now a full general, faced numerous problems trying to bring the AEF to France, the most pressing of which entailed amalgamation. The Allies, dubious of U.S. military preparedness, sought to amalgamate American soldiers and units into existing French and English units. Pershing steadfastly resisted this notion. He did allow early-arriving regular units to serve under Allied leadership, but only at the division or higher level and mainly as a form of battlefield familiarization. These early arriving American units served with distinction during the dark days of the German Spring 1918 offensive. As the Germans gained ground, Pershing agreed to American divisions helping in the defense, stating that, “the American people will hold it as a high honor to take part in the present battle.”

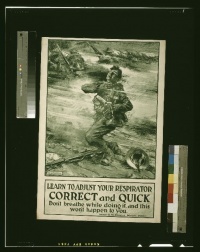

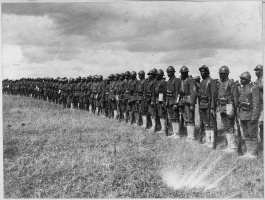

Even after these concessions, Pershing continued to agitate for a U.S.-commanded sector of the front and the full concentration of U.S. manpower under U.S. control. Pershing benefitted from the full political backing of Wilson and the Secretary of War, Newton D. Baker (1871-1937). The general enjoyed a free hand to manage and run his command in France. Pershing did, however, demur somewhat to political necessity; an early advocate of African American soldiers serving in combat, he backed off, realizing the political imbroglio this would cause the Wilson administration so in need of Southern legislative support. Two African American divisions formed and fought during World War I. Pershing did little to help the 92nd Division succeed and turned the provisional 93rd Division over to the French Army, where it fought successfully. Arriving in France in June 1917, Pershing immediately put his staff to work untangling the congested French rail and road networks needed to bring the AEF ashore and supply them with war materials. He also built training camps for the raw American units arriving in France during the autumn of 1917. These camps institutionalized best practices by veteran French and English units, particularly the minutiae of trench warfare. Some American divisions rotated back and forth to Allied sectors of the front in order to gain battlefield familiarization and acquire the knowledge needed to serve as future trainers. At the same time, these camps also taught specialized skills associated with “modern” warfare – machine gun use, artillery adjustment, gas attack defense, and the use of armored formations.

Having witnessed how poor staff work could lead to disaster during the Mexican campaign, Pershing ordered his staff to create a Staff School, modeled after the Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, to train fresh officers on the intricacies of staff work at the division and corps level. One of Pershing’s most innovative trends entailed the integration of multiple “arms” within the AEF: artillery, aircraft, and armor. While the U.S. Army had little training in these branches prior to 1917, Pershing helped to incorporate their application into both the planning and execution of the AEF. Much of this was designed to create dynamism within the planning of the American forces. Many American planners believed that the Entente powers had lost their offensive spirit after three years of war and that aggressive leadership that leveraged all the elements brought to bear by the U.S. Army would create opportunities for localized, but rapid, breakthroughs. With this in mind, AEF staff officers planned first- and second-day objectives for upcoming operations far forward of the line of departure, believing that brisk and bold action would allow American units to escape the grinding attrition of trench warfare.

The St. Mihiel Offensive, Pershing and the AEF’s first independent operation, appeared to validate open-warfare doctrine. U.S. forces attacking into the salient on 12 September 1918 unwittingly caught German forces withdrawing from their overextended positions. The U.S. 1st Army enjoyed rapid successes and quickly seized most of their objectives. Pershing was ecstatic. The victory at St. Mihiel validated the U.S. army as a fighting force capable of operating as a full coalition partner. Some French and English politicians and military men would continue to question American combat effectiveness up to the Armistice, but the loudest critics now went silent. The Meuse-Argonne Offensive, fought from 26 September up to the Armistice, proved a far more grinding affair and did not offer the same rousing successes. Stout German defenses, along with the American’s rigid adherence to divisional boundaries and open-warfare doctrine, led to the isolation of some units and the deadening of the initial assault’s momentum. The final breakthrough during early November, however, helped to unhinge the German defenses on the Western Front.

At the war’s conclusion, Pershing found himself in political hot water, for perhaps the only time during the war, when he advocated against an Armistice with Germany and instead believed that the Allies should attack into Germany and occupy it completely. He would later retract his statements, avoiding a reprimand from Wilson, but many, including President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945), would later claim that such an action might have prevented the rise of Germany and World War II.

Pershing’s Legacy↑

Pershing does not receive just credit for birthing the modern American military. Many scholars point to the AEF’s strikingly high casualty rate, as well as the attritional offensive in the Meuse-Argonne, as evidence either of Pershing’s naiveté or his overconfidence. At the strategic level, many historians lay more import on the rapid infusion of U.S. dollars, equipment, and food to the eventual Allied victory than on the combat prowess of the AEF. While these notions hold elements of truth, they disregard the momentous amount of work needed to create the AEF. At the onset of World War I, the United States possessed a small land force that specialized in constabulary duty. Pershing quickly oversaw the modernization and professionalization of the force. Pershing incorporated tanks, automobiles, and airplanes (the tools of modern war) into the AEF, borrowing surreptitiously from Allied doctrine and pre-World War experience to create a new American way of war. At the same time, Pershing institutionalized and formalized the modern American military staff system. The U.S. Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth enjoyed the largest victory during the Great War. Pershing filled his staff with Staff College graduates and emphasized the primacy of planning during operations, a novel concept for the American army. His establishment of replica Staff Schools in France that mirrored the Leavenworth experience codified the Staff College’s best practices among a generation of regular and volunteer officers.

The most enduring facet of Pershing’s legacy entailed his ability to surround himself with talent. Hugh Drum (1879-1951), Terry Allen (1888-1969), Douglas MacArthur (1880-1964), George Marshall (1880-1959), George Patton (1885-1945), Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. (1887-1944) – all of these future generals either served on Pershing’s staff or as direct subordinates. The World War II generation of American leaders thus spent World War I working with and learning from General John Pershing.

Andrew J. Forney, United States Military Academy

Section Editor: Lon Strauss

Selected Bibliography

- Coffman, Edward M.: The war to end all wars. The American military experience in World War I, Lexington 1998: University Press of Kentucky.

- Cooke, James J.: Pershing and his generals. Command and staff in the AEF, Westport 1997: Praeger.

- Grotelueschen, Mark E.: The AEF way of war. The American army and combat in World War I, Cambridge; New York 2007: Cambridge University Press.

- Nenninger, Timothy K.: 'Unsystematic as a mode of command'. Commanders and the process of command in the American Expeditionary Forces, 1917-1918, in: Journal of Military History 64/3, 2000, pp. 739-768.

- Rainey, James W.: The questionable training of the AEF in World War I, in: Parameters, 1992, pp. 89-103.

- Smythe, Donald: Guerrilla warrior. The early life of John J. Pershing, New York 1973: Scribner.

- Trask, David F.: The AEF and coalition warmaking, 1917-1918, Lawrence 1993: University Press of Kansas.

- U.S. Army Center of Military History (ed.): American armies and battlefields in Europe, Washington, D.C. 1992: U.S. Army Center of Military History.

- Vandiver, Frank Everson: Black Jack. The life and times of John J. Pershing, College Station 1977: Texas A & M University Press.