Introduction↑

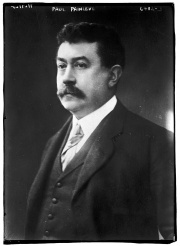

As an internationally renowned mathematician, Paul Painlevé (1863-1933) was first known to the general public as a Dreyfusard during the 1899 Rennes trial testimony and a supporter of nascent aviation by 1908. Elected to the Chamber of Deputies of Paris in 1910, he specialized in defense issues. He had just been re-elected when the war started.

During the First World War↑

In 1914-1915, Painlevé advocated in the Committees of the Chamber of Deputies (War and Navy) for greater parliamentary control of the government and greater government control of the French High Command. The head of the Inventions Committee of the Ministry of War, Painlevé was also a mathematician who appointed scientists and laboratories to devise a new science of war. In October 1915, he took the lead of a specially designed Minister of Public Instruction, Fine Arts and Inventions interesting National Defense, allowing him to rationalize and amplify the mobilization of science.

Minister of War↑

As minister of war beginning in March 1917, he had severe doubts about the Nivelle offensive. The failure of the offensive allowed him to impose a reorganization of the High Command. Endorsed by Painlevé, the new commander in chief, Philippe Pétain (1856-1951), fought against mutinies with a two-sided policy: “repression” for the leaders of the mutineers and a “cure” to improve soldiers’ everyday life and to launch only well-prepared offensives.

Painlevé also oversaw the Franco-American collaboration aimed at breaking through the frontlines. Aware of the risk of the Eastern Front collapsing, he supported Aleksandr Kerenskii’s (1881-1970) government. He worked with the British to get Greece to join the Allied forces and supported a military intervention in Italy after the Battle of Caporetto and the establishment of a Supreme War Council of Allied forces. When he authorized peace talks with the central powers, he took a stand not to relinquish Alsace and Moselle. The government he formed in September 1917 would be the only one during the First World War to fail a confidence vote (November 1917). Weakened on his right by treason cases, he could also no longer count on support from socialists.

After the War↑

In 1919 he came under heavy attack by the extreme right for his role as war minister. He ardently defended his position in two publications: "The truth about the 1917 offensive" and "The offensive of April 16, 1917. The legend and the truth." Again, in the context of electoral campaign preparation he repeated his position in 1923 with the book How I named Foch and Pétain. Continuously re-elected in Paris until his death in 1933, he was minister of war between 1925 and 1929 and air minister. In 1925, he led two governments. In 1933, only the Communists (who reproached his repression of the mutinies in 1917) refused to vote in his state funeral and his burial in the Pantheon.

Anne-Laure Anizan, Independent Scholar

Section Editor: Emmanuelle Cronier

Translator: Emmanuelle Cronier

Selected Bibliography

- Anizan, Anne-Laure: Painlevé et la guerre (1908-1933). Science poliade et défense nationale, in: Durand, Antonin / Mazliak, Laurent / Tazzioli, Rossana (eds.): Des mathématiciens et des guerres. Histoires de confrontations (XIXe-XXe siècle). Actes du colloque tenu à l'Institut des sciences de la communication du CNRS (ISCC) le 8 février 2012, Paris 2013: CNRS éditions, pp. 39-53.

- Anizan, Anne-Laure: 1914-1918, le gouvernement de guerre, in: Histoire@Politique 22/1, 2014, pp. 215-232.

- Anizan, Anne-Laure: Les gouvernements successifs, in: Nivet, Philippe / Coutant-Daydé, Coraline / Stoll, Mathieu (eds.): Archives de la Grande Guerre. Des sources pour l'histoire, Rennes; Paris 2014: Presses universitaires de Rennes; Archives de France, pp. 203-209.

- Anizan, Anne-Laure: Paul Painlevé. Science et politique de la Belle Époque aux années trente, Rennes 2012: Presses universitaires de Rennes.