Freedom Fighting↑

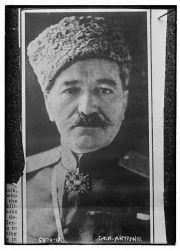

As a youth, Antranik Ozanian (1865-1927) became imbued with the ideals of freedom for his oppressed people, whose situation was exacerbated under the reign of Abdülhamid II, Sultan of the Turks (1842-1918). In 1892, Antranik joined the Armenian Revolutionary Federation,[1] which had been founded two years earlier in Tiflis. During the Hamidian massacres of 1894-1896, he protected the Armenian peasantry of Moush and Sasun against Turkish and Kurdish oppressors. 1,200 Ottoman soldiers besieged the Holy Apostles Monastery in Moush in 1901. Antranik and a handful of his fedayis[2] fought off their attacks. Disguised as an Ottoman officer, Antranik went the rounds of the entire guard, talking to them in excellent Turkish, while at the same time showing the way out to his own men.[3] During the Sasun uprising in 1904, isolated and lacking resources, Antranik’s fighters nonetheless came near to shaking off the Ottoman yoke in Armenian-populated provinces.[4] After the uprising, Antranik left the Ottoman Empire, eventually arriving in Europe where he published a book on military tactics. In 1907, he voiced his discontent over the Dashnaks’ cooperation with the Young Turks,[5] and left the party.

First Balkan War↑

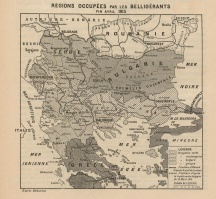

In 1907, Antranik settled in Sofia. During the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913, as a commander of Armenian auxiliary troops in the Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Volunteer Corps within the Bulgarian army, he led a company of a few hundred volunteers. In the words of Leon Trotsky (1879-1940), “at the head of the Armenian volunteer troop stood Antranik, a hero of song and legend”.[6] Antranik was given the rank of first lieutenant by the Bulgarian command. An audacious and farsighted commander, he distinguished himself in several battles against the Turks and was decorated with the Order of Bravery. However, in May 1913, Antranik disbanded his troops and, foreseeing the war between Bulgaria and Serbia, retired to a village near Varna, where he lived until the outbreak of World War I.

World War I↑

During the war, Antranik emerged as an accomplished military leader, gaining fame due to his courage and the tactics he employed to defeat the Turks. During the early stage, Antranik fought as commander of the First Armenian Volunteer Battalion[7] within the Russian Caucasus Army. Russian successes on the Caucasus Front hinged largely on the combat performance of his troops. When, in April 1915, the Ottoman army besieged Van, Antranik helped Armenian resistance fighters organise an effective defence. In May, he entered Van, lending support to the Russian army to take control of several areas to the south of Lake Van. In 1916, Bitlis and Moush were captured from the Ottoman forces with the support of Antranik’s troops.

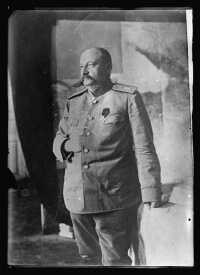

The situation changed in 1916, when the Russian command decreed the demobilisation of the Armenian battalions. Disappointed, Antranik left the front and sought to provide relief to the survivors of the Armenian Genocide. After the 1917 February Revolution, the Russian army retreated, leaving the Armenian units to stand face to face against an Ottoman force that vastly outnumbered them. Along with several thousand Armenian irregulars, Antranik’s troops were able to hold the front for five months after the defection of roughly half a million Russians. By one of his last decrees, the commander of the Russian Caucasus Army Nikolaĭ Yudenich (1862-1933) decorated Antranik with the Cross of St George and praised him as a brave and experienced commander who understood the combat situation well.

In May 1917, Russia’s Provisional Government put Ottoman Armenia under civil administration and, for two months in 1918, Antranik was a governor of the administration for Western Armenia. In December 1917, the Russian command authorised the formation of the Armenian Army Corps, with Antranik put in command of the Western Armenian division. Promoted to major general, he led the defence of Erzurum against a considerably superior Ottoman army but was forced to retreat eastward in March 1918. His leadership was instrumental in organising an escape route for the Armenian population of Van to Eastern Armenia. In April, the Ottoman army invaded Eastern Armenia.

First Republic of Armenia↑

In May, the Turks stood at the distant approaches to Yerevan but were defeated at Sardarabad, Bash Abaran, and Karakilisa. These victories paved the way for the independence of Armenia on 28 May 1918. Antranik refused to acknowledge the independent republic, because it included only a small portion of Armenians' historical habitat. With his Special Striking Division, he fought the encroaching Turks independently from the government, concentrating on the area between Karabakh and Zangezur. A born strategist, he understood that the defence of Zangezur was crucial as it was a strip of land between two hostile nations, Turkey and Azerbaijan. Without Antranik’s resolve to defend the region, only a miracle could have saved 60,000 Armenians of Zangezur from complete annihilation by the Turco-Azeri forces.[8]

In the final phase of the war, the Army of Islam penetrated these areas, destroying Armenian villages in the mountain range between Karabakh and Zangezur. Antranik rushed to the villagers’ aid, but as he reached the outskirts of Karabakh, the war ended. British General William M. Thomson (1877-1963) requested Antranik not to enter Karabakh, promising a favourable arrangement at the Paris Peace Conference. Antranik trusted Thomson, and withdrew. As a result, Karabakh with its indigenous Armenian population remained Azerbaijani throughout the pre-Soviet and Soviet period, all dating from Antranik’s trust of the word of a British officer.[9] Arriving in March 1919 at the Mother See of the Armenian church in Etchmiadzin, Antranik disbanded his division and handed their weapons and ammunition to Gēorg V, Catholicos of Armenians (1847-1930).

Departure, Last Years, and Death↑

In April 1919, Antranik left Armenia due to disagreements with the Dashnak government and the political machinations of the British in Transcaucasia. He travelled around Europe, where he tried to persuade the Allied Powers to occupy Western Armenia, and to the United States, where he lobbied for a mandate for Armenia. In 1922, he settled in Fresno, California, where he directed a campaign which raised significant funds for the relief of Armenian war refugees. Antranik died in Richardson Springs, California, on 31 August 1927. It was planned to take his remains to Armenia for burial, but when they arrived in France, the Soviet authorities declined to give permission. The remains were conveyed to Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. In 2000, they were transferred to Yerevan, Armenia.

Tigran Martirosyan, University of Amsterdam

Section Editors: Erol Ülker; Pınar Üre

Notes

- ↑ A political party also known as Dashnaktsutyun, or Dashnak for short.

- ↑ Armenian militia groups operating in reaction to the murder of Armenians and pillage of Armenian villages by Turkish troops and Kurdish irregulars.

- ↑ Weissmann, George / Williams, Duncan (eds.) / Trotsky, Leon: The War Correspondence of Leon Trotsky. The Balkan Wars 1912-13, New York 1980, p. 250.

- ↑ Walker, Christopher J.: Armenia. The Survival of a Nation, London 1990, p. 177.

- ↑ A coalition of nationalist groups whose members formed the wartime government that directed local authorities and Ottoman soldiers to deport or execute the Armenians.

- ↑ Weissmann, Trotsky 1980, p. 247.

- ↑ In Russian, druzhina. Practically it may be translated as “squad”, a force about 1,000-strong.

- ↑ Chalabian, Antranig: Dro (Drastamat Kanayan). Armenia’s First Defence Minister of the Modern Era, Los Angeles 2009, p. 409.

- ↑ Walker, Armenia 1990, pp. 271-272.

Selected Bibliography

- Bloxham, Donald: The great game of genocide. Imperialism, nationalism, and the destruction of the Ottoman Armenians, Oxford 2005: Oxford University Press.

- Chalabian, Antranig: General Andranik and the Armenian revolutionary movement, Southfield 1988: Chalabian (Self Published).

- Hovannisian, Richard G.: The Republic of Armenia. The first year, 1918-1919, volume 1, Berkeley 1971: University of California Press.

- Simonyan, Hrachik: Andraniki jamanake (Andranik’s time), Yerevan 1996: Kaisa.

- Trotsky, Leon: Andranik and his troop: The Balkan Wars 1912-13. The war correspondence of Leon Trotsky, New York 1980: Monad Press.

- Walker, Christopher: Armenia. The survival of a nation, London 1990: Routledge.