Introduction↑

The traditional picture of the British economy between 1914 and 1918 has stressed the government’s reluctance to abandon the nation’s traditional, market-led approach to the economy during the war – dubbed “business as usual” by Winston Churchill (1874-1965) – and the prescience of a few dynamic, far-sighted individuals who recognised the need for greater central direction of the British war effort. David Lloyd George (1863-1945) has been a prominent figure in this “statist-corporatist” approach to wartime production.[1] As Chancellor of the Exchequer, Minister of Munitions, and latterly as Prime Minister, Lloyd George played a central role in organizing Britain’s response to the demands of the First World War. He was greatly responsible for the increasing scale and spread of state intervention into areas of the economy previously considered to be wholly of concern to the private sector, and pursued a policy of government control over industries deemed essential to the war effort.[2]

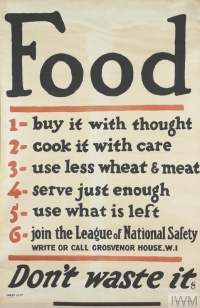

Elsewhere, economic historians have considered the impact on Britain of the dislocation of international trade flows, and the ways in which Britain coped with the wartime disappearance of imports of key supplies rendered inaccessible through either their association with enemy powers or the limited capacity of British shipping. The area of food supply was crucial here. Britain was a pre-war importer of the majority of her foodstuffs. The poor harvests of 1916-1917, combined with the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare by Germany in February 1917, were tackled by increased government control of food supplies and a shift in agricultural practice away from dairy to arable produce.

The net result of these activities across industry and agriculture was that Britain was able to contribute a significant share towards the Allies’ superabundance of materiel in 1918 whilst simultaneously maintaining health and morale on the home front. Consequently, Britain was not seriously troubled by the shortages that contributed to discontent and revolution within the Central Powers and Russia.

The Mobilization of Industry↑

Between 1914 and 1918, the British economy was faced with the challenges of allocating raw materials to and raising output in a range of war-related industries, coordinating the distribution of finished goods to fighting troops spread across the globe, balancing the demands of industry, the army, and the navy for the limited supply of physically fit male labour, and ensuring the continued support for the war effort among both employers and labour representatives. As the war continued and the scale of the effort required to win it expanded, tensions between the maintenance of the pre-war economy and the need for state intervention came to the fore.[3]

Far from pursuing an entirely hands-off approach in August 1914, from the outset the government recognised the need for increased state control in the economy. Most of the privately-owned railway companies in Britain (but not Ireland) were placed under the oversight of the Railway Executive Committee immediately upon the outbreak of war, whilst competitive tendering for government contracts in the clothing trade (particularly in relation to the provision of uniforms for the greatly expanded army) was eliminated by the Director of Army Contracts in late 1914. However, government intervention did not extend to manpower in the first instance. This, alongside an initial decision to retain significant responsibility for the coordination of procurement within the War Office, had profound implications for Britain’s ability to respond to the increased demands for munitions and machinery of war. By mid-1915, 23.8 percent of male employees in the chemical and explosives industry, 23.7 percent of those in electrical engineering, 21.8 percent of miners, 19.5 percent from the engineering trades, 18.8 percent from the iron and steel industry, and even 16.8 percent of those in small arms manufacturing had enlisted.[4]

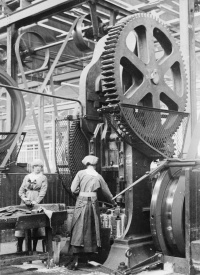

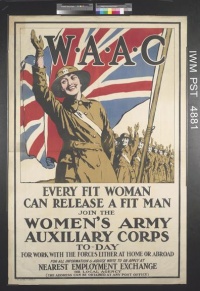

The central direction of manpower in the second half of the war under the Ministry of National Service somewhat reversed such trends, as men in so-called non-essential occupations were increasingly conscripted rather than those in more explicitly applicable trades (for example, 63 percent of men employed in commerce, finance, and services had been recruited by the armed forces by July 1918, as opposed to a national average of 46 percent of males).[5] Men who remained in civilian trades fought strongly against any attempts to "dilute" the labour force with unskilled, cheaper labour (particularly that of women), arguing that their employers should not be allowed to use the war to enrich themselves at their employees’ expense. The so-called Treasury Agreement of 1915 saw major employers such as Vickers and Armstrongs agree to limit their profits for the duration of the war, whilst trade unions agreed to a temporary dilution of the labour force until the end of the conflict.[6] The increased use of female labour was crucial to Britain’s industrial mobilisation. Across civil employment as a whole, the female proportion of the workforce increased from 23.7 percent to 37.7 percent during the war. Yet in some industrial fields the influx of female labour was more pronounced: in the metal trades female labour went from 9.4 percent to 24.6 percent of the overall labour force, in chemicals the rise was 20.1 percent to 39 percent, and in government establishments (which included the newly established munitions factories) the increase was 2.6 percent to 46.7 percent.[7]

The so-called “shells scandal” provided the most prominent example of shortage caused by inadequate wartime planning and led both to the demobilisation of men in key industries (such as iron ore mining) and the creation of the Ministry of Munitions to centrally direct the national effort to increase wartime output. The failure of the Battle of the Somme – fought using the first fruits of the ministry’s labours from July 1916 – to dislodge German troops from French soil, contributed greatly to a change in direction for Britain’s industrial mobilisation. Herbert Henry Asquith (1852-1928) was replaced as Prime Minister in December 1916 by David Lloyd George, who had earlier vowed to fight Germany to a knock-out. A central component of Lloyd George’s administration was the proliferation of new government departments to oversee ever more aspects of the British war effort. Twelve new ministries, frequently headed by so-called men of “push and go” from business rather than political backgrounds, were established to manage shipping, food production and distribution, information, and reconstruction among others.[8]

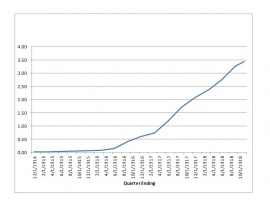

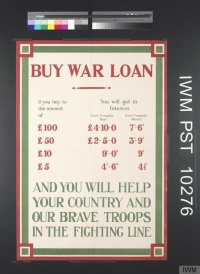

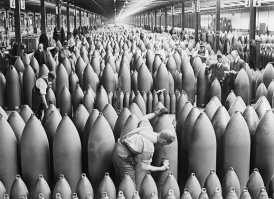

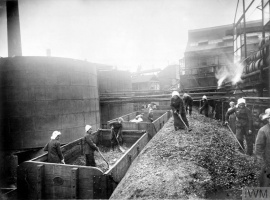

From a combination of patriotism and economic forces that encouraged industries to commit to the war effort before late 1916, state action compelled an increasing dedication of British industry to war-related production in the second half of the war. By 1917, government spending comprised 38.7 percent of gross domestic product, up from just 8.1 percent before the war.[9] By the middle of the following year, the state directedly employed over 3.1 million people across the building, mining, metals and chemicals, clothing, food, paper and printing, wood, and ordnance trades and within the civil service.[10] 90 percent of activity in the metals industry and 79 percent of that in chemicals was dedicated to war-related rather than civilian-focused work. The increased demand for munitions drove expansion in the output of steel during the war, which reached 9.7 million tons in 1917, or 25 percent above 1913 levels.

The implications of direct economic management were most stark in the production statistics for munitions. From a total of 500,000 shells produced in the first five months of the war, by 1917 the munitions industry manufactured more than 50 million shells a year for the British army to pump into the German lines. A year’s worth of pre-war production in light munitions could be completed in just four days by 1918. This remarkable increase took place against a backdrop of increasing industrial unrest in Britain as the war progressed. Trade union membership grew from 4.1 million to 6.5 million (38.1 percent of the working population) in spite of the fall in the size of the civilian labour force, and more strikes took place in Britain as the “patriotic restraint” of the war’s early years was worn away. From a wartime low of 2,446,000 working days lost to strikes in 1916, the final year of the war witnessed 1,165 separate strikes that cost the war economy 5,875,000 working days.[11]

From a slow start, by the end of the war the British economy was thoroughly mobilized for war. Through the Railway Executive Committee, Ministry of Shipping, and Canal Control Committee the government controlled the means of transportation. The Coal Controller and Minister of Munitions commanded the fuel, raw materials, and factories that manufactured the vast quantity of industrial products demanded by a modern army, and the Ministries of Food and Agriculture determined the nature of the diet consumed by the population. The state was the largest producer of goods in the country and oversaw a significant rise in economic activity.[12] Between 1914 and 1918, British gross domestic product rose by approximately 14 percent whilst Germany’s, by comparison, shrank by 27 percent. According to Stephen Broadberry and Peter Howlett, Britain managed an “impressive production effort in all parts of the economy, including services and agriculture as well as munitions and other industries”.[13] Britain’s pre-war perceived weaknesses as an island nation, reliant upon imports for key raw materials and food supplies, did not outweigh the advantages incurred through her possession of the world’s largest shipping fleet and her comparative distance from the destruction caused by the fighting. Consequently, as her enemies became exhausted and experienced ever increasing shortages as the war progressed, Britain remained able to sustain a more total war effort than at any previous point in her military history.

Trade and Blockade↑

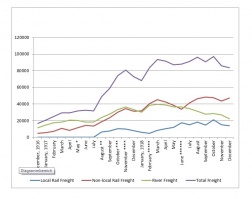

At the outbreak of the First World War, Britain was both the largest importer and exporter of goods in the world. It was – as the only major free trade economy – “the most exposed and integrated into the trade of the world”.[14] Britain was an importer of food, raw materials, and agricultural necessities (such as fertiliser and animal feed) and an exporter of manufactured goods and coal. The war dislocated trade flows and patterns, particularly those between now rival nations, which acted as a catalyst for domestic production and substitution. Britain’s possession of 40 percent of the world’s merchant shipping tonnage, and the world’s largest and most powerful navy, allowed it to maintain and increase its pre-existing import trade advantage over Germany as the war continued.

The disruption to world trade from August 1914 had both short and long-term effects for the British economy. In the short term, Britain lost access to a wide range of products imported from the Central Powers, including magnetos for motor car and aero engines, optical equipment (such as those used to manufacture glasses), chemicals used in munitions, and the dyes used to colour the khaki uniforms worn by British troops. New companies, dedicated to import substitution, emerged to ensure continued supplies of these key products.[15] As the war progressed – and particularly following the advent of unrestricted submarine warfare in 1917, Britain lost access to markets abroad as limited shipping capacity was redirected to service the war effort. As an example, in 1913 around 80 percent of output from the Lancashire cotton industry was manufactured for shipment abroad (nearly one-quarter of British exports by value). India took some 40 percent of Lancashire cotton exports in 1913, but as shipping became scarce the Indian market was left open to competitors. Between 1913 and 1919, Lancashire’s share of imports to India fell from 97 percent to 77 percent, with Japanese imports rising from 1 percent to 21 percent in the same period. Britain struggled to regain such markets in the interwar period.[16]

Shipping was also critical to the German war effort, and heavily influenced by British decisions. British strategists recognized prior to 1914 that Germany was even more exposed to the dislocation of overseas trade than was Britain. This has led to recent suggestions that the naval blockade was part of a wider economic warfare strategy designed by the Admiralty to bring about a rapid collapse of the German financial system, the disorganization of its economy, and paralysis of its military. By so doing, the argument runs, Britain could have avoided the engagement of a large army and reduced the bloodshed suffered by her forces engaged on the Western Front battlefields.[17]

The British sought to exclude Germany from world markets, and by 1915 German imports had plummeted to around 55 percent of their pre-war levels.[18] These figures would have been even larger, but the vocal opposition of other government departments to the Admiralty’s plans and the need to appease neutral interests (most notably that of America) stymied the development of the blockade until the creation of a Ministry of Blockade in early 1916. Phillip Dehne has described the period until the ministry’s creation as a “classic example of Britain improvising the Great War”.[19] Following America’s entry into the war German import levels eroded still further, as American exports to neutral countries decreased by almost 75 percent of their 1915-16 values.[20] Yet the ministry provided further benefits for Britain, by simultaneously denying Germany’s access to world markets and compiling vast amounts of information on global trade for dissemination amongst British businessmen.[21] This knowledge was crucial to the identification and exploitation of new export markets following the war.

In addition to reducing German shipping activity, the Allies both curtailed the shipment of goods to neutral nations known to be re-exporting to Germany – most notably the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Denmark – and entered into preclusive purchasing agreements to buy up neutral produce at prices the Central Powers could not match. Furthermore, as demonstrated by the terms of the Anglo-Dutch agreement of 1916, the guaranteed price offered by Britain was dependent upon the Dutch agricultural co-operatives agreeing to half their deliveries to Germany. Between 1916 and 1918, German imports of flour, bread grains, and meat (including meat products) fell by 73 percent, 82 percent, and 93 percent respectively. By the end of the war German imports from Scandinavia were also substantially below pre-war levels.[22]

Agriculture↑

In 1914, the proportion of the British population engaged in agriculture was lower than in all of the other belligerents. Contemporary observers perceived that this placed Britain at a disadvantage in the event of a protracted war. As nations like Russia, pre-war exporters of food with large peasant populations able to feed themselves, redirected exports to service the demands of the home market, Britain would quickly starve.[23] In practice, the pre-war contraction of British agriculture meant that plentiful reserves of underused land existed across the country. The availability of land combined with higher prices offered to farmers for their goods, which incentivised production to replace decreases in imports.

According to Peter Dewey, “the most striking feature of wartime agriculture was its stability”.[24] Whereas in continental Europe, agricultural production fell by about one-third during the war, the supply of food in Britain was maintained almost intact. This was achieved despite the loss to British farmers of two essential factors of production from 1914: alongside men from the agricultural sector, the army required colossal numbers of horses. Following military impressment, the number of horses available for agriculture in Britain fell from 926,820 in 1914 to 858,032 the following year.[25] Supplies of fertiliser and animal feeds were also heavily affected by the dislocation of trade, but the government was initially reluctant to label agriculture as an “essential” war industry and thereby acquire control over its direction.

In the opening two years of the war actual food shortages were localized and of relatively short duration. Nevertheless, complaints about increased food prices and accusations of profiteering were prevalent throughout the war: “as the war progressed, shortages and inflationary pressures increased, and demands for state intervention became more persistent”.[26] The Food Production Department was constituted in January 1917, with a policy to utilise Britain’s underexploited land for arable cultivation, guarantee prices for farmers, and provide minimum wages of 25s per week for farm workers.[27] Farmers demonstrated a willingness to cooperate with directives issued by the Food Production Department, but were restricted by shortages of labour, horses, machinery, fertiliser, and animal feeds.

Attempts to relieve the shortage of labour included the formation of Agricultural Companies, comprised of soldiers in medical category C3, the temporary return of skilled farmworkers (most notably ploughmen) from the front, prisoners of war (POWs), women, and children. By the end of the war, 60.5 percent of POWs available for work in Britain were employed in agriculture, whilst the Women’s Land Army provided a maximum working strength of 16,000 to complement the approximately 180,000 village women employed in agriculture. Across Britain, increasing numbers of children obtained exemptions from school to engage in agricultural work during the harvest season and worked part-time on farms outside of school hours.[28] Their contributions, in Dewey’s estimates, reduced the fall in the agricultural labour supply from 9 percent of the pre-war total in 1916 to around 4 percent by 1918.

Their endeavours meant that home food production was restored to pre-war levels, but output in meat and milk decreased in the final year of the war for want of animal feed. However, each ton of home-grown food reduced the stress placed on British shipping for imported goods, and nationwide rationing in Britain was implemented late in the war compared to other European countries. It was not until early 1918 that rationing was instituted in Britain, and British consumers did not suffer the same decline in nutritional standards as their counterparts overseas. The content of the British diet changed more than its nutritional value. At its lowest point, in 1917, the calorific value of the average British diet was only 4 percent lower than in 1913, and across the war as a whole the diets and health of women and poor children improved.[29] To maintain the calorific consumption of the population, meat was replaced with bacon, brown bread substituted for white bread (but bread itself was not rationed, unlike elsewhere), and margarine replaced butter.[30] The British diet may have become more bland and monotonous as the war progressed, but Britain did not come close to succumbing to the starvation predicted by pre-war commentators. Ultimately, British agriculture performed well between 1914 and 1918.

Conclusion↑

The industrial revolution fundamentally altered the character of warfare and led to a more substantial and wide-ranging set of demands being made upon the economy by the armed forces than ever before. The First World War compelled a number of changes in the composition and governance of the British economy. These changes were reactive – particularly to the diminution of the male labour force created by mass recruitment and the material-intensive nature of the fighting on the Western Front – and were predominantly founded upon a desire that the war would not become as vast or long lasting as it did. The inconclusive nature of the military operations on the Western Front in 1916 proved the catalyst for a more comprehensive approach to war-making from 1917 onwards. The replacement as prime minister of Asquith with Lloyd George in December 1916 exemplified the British government’s desire to replace the ad hoc solution of organisational problems as they arose with a more comprehensive, centrally directed approach to the prosecution of the war effort.

The transition from a market-driven to a command economy aided the development of a war effort capable of providing the armed forces with vast quantities of materiel, whilst simultaneously protecting the home front from the most severe privations that impacted morale in the defeated powers and Russia.

Christopher Phillips, Independent Scholar

Section Editor: Adrian Gregory

Notes

- ↑ Millman, Brock: Managing Domestic Dissent in First World War Britain, London 2000, p. 167.

- ↑ French, David: British Economic and Strategic Planning, 1905 – 1915, London 1982.

- ↑ Broadberry, Stephen / Howlett, Peter: The United Kingdom during World War I. Business as usual?, in: Broadberry, Stephen / Harrison, Mark (eds.): The Economics of World War I, Cambridge 2005, pp. 206-34.

- ↑ Simkins, Peter: Kitchener’s Army. The raising of the new armies, Manchester 1988, p. 111.

- ↑ Grieves, Keith: The Politics of Manpower, 1914-1918, Manchester 1988; Dewey, Peter: The new warfare and economic mobilization, in: Turner, John (ed.): Britain and the First World War, London 1988, pp. 71-84 (p. 75).

- ↑ French, British Economic and Strategic Planning 1982, pp. 162-3.

- ↑ Broadberry / Howlett, The United Kingdom 2005, p. 207.

- ↑ Grigg, John: Lloyd George. War leader 1916-1918, London 2002.

- ↑ Broadberry / Howlett, The United Kingdom 2005, p. 210.

- ↑ Winter, Jay: The Great War and the British People, London 1985, p. 47.

- ↑ Wrigley, Chris: Organized labour and the international economy, in Wrigley, Chris (ed.): The First World War and the International Economy, Cheltenham 2000, pp. 201-15.

- ↑ Tawney, R.H.: The abolition of economic controls, 1918-1921, in: Economic History Review 13 (1943), pp. 1-30 (pp. 2-3).

- ↑ Broadberry / Howlett, The United Kingdom 2005, p. 229.

- ↑ Edgerton, David: The Rise and Fall of the British Nation. A Twentieth Century History, London 2018, p. 10.

- ↑ Macleod, Kay / Macleod, Roy: War and economic development. Government and the optical industry in Britain, 1914-1918, in Winter, Jay (ed.): War and Economic Development. Essays in memory of David Joslin, Cambridge 1975, pp. 165-204; Tynan, Jane: British Army Uniform and the First World War. Men in khaki, London 2013.

- ↑ Fowler, Alan: Impact of the First World War on the Lancashire cotton industry and its workers, in Wrigley, Chris (ed.): The First World War and the International Economy, Cheltenham 2000, pp. 76-98.

- ↑ Lambert, Nicholas A.: Planning Armageddon. British economic warfare and the First World War, Cambridge, MA 2012.

- ↑ Ferguson, Niall: The Pity of War, London 1998, pp. 252-3.

- ↑ Dehne, Phillip: The Ministry of Blockade during the First World War and the demise of free trade, in: Twentieth Century British History 27/3 (2016), pp. 333-56, https://doi.org/10.1093/tcbh/hww027.

- ↑ Ferguson, Pity of War 1998, pp. 252-3.

- ↑ Dehne, Ministry of Blockade 2016.

- ↑ Stevenson, David: With Our Backs to the Wall. Victory and Defeat in 1918, London 2011, p. 431.

- ↑ Broadberry, Stephen / Harrison, Mark: The economics of World War I. An overview, in Broadberry, Stephen / Harrison, Mark (eds.): The Economics of World War I, Cambridge 2005, pp. 3-40 (p. 18).

- ↑ Dewey, Peter E.: British Agriculture in the First World War, London 1989, p. 240.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 61.

- ↑ Gazeley, Ian / Newell, Andrew: The First World War and working-class food consumption in Britain, in: European Review of Economic History 17/1 (2013), pp. 71-94, https://doi.org/10.1093/ereh/hes018.

- ↑ Dewey, British Agriculture 1989, p. 93.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Gregory, Adrian: The Last Great War. British society and the First World War, Cambridge 2008, pp. 285-6.

- ↑ Winter, Great War 1985, p. 216.

Selected Bibliography

- Adams, R. J. Q.: Arms and the wizard. Lloyd George and the Ministry of Munitions, 1915-1916, College Station 1978: Texas A & M University Press.

- Broadberry, Stephen N. / Harrison, Mark (eds.): The economics of World War I, Cambridge; New York 2005: Cambridge University Press.

- Broadberry, Stephen N. / Howlett, Peter: The United Kingdom during World War I. Business as usual?, in: Broadberry, Stephen N. / Harrison, Mark (eds.): The economics of World War I, Cambridge; New York 2005: Cambridge University Press, pp. 206-234.

- Burk, Kathleen (ed.): War and the state. The transformation of British government, 1914-1919, London; Boston 1982: Allen & Unwin.

- Dewey, Peter E.: British agriculture in the First World War, London 1989: Routledge.

- Ferguson, Niall: The pity of war, New York 1999: Basic Books.

- French, David: The strategy of the Lloyd George coalition, 1916-1918, Oxford; New York 1995: Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press.

- French, David: British economic and strategic planning, 1905-1915, London; Boston 1982: Allen & Unwin.

- Grieves, Keith: The politics of manpower, 1914-1918, New York, N.Y 1988: St. Martin's Press.

- Lambert, Nicholas A.: Planning armageddon. British economic warfare and the First World War, Cambridge; London 2012: Harvard University Press.

- Lloyd, E. M. H.: Experiments in state control at the War Office and the Ministry of Food, Oxford; London; New York 1924: Clarendon Press; H. Milford.

- Lloyd-Jones, Roger / Lewis, Myrddin John: Arming the Western Front. War, business and the state in Britain 1900-1920, London; New York 2016: Routledge; Taylor & Francis Group.

- Offer, Avner: The First World War. An agrarian interpretation, Oxford; New York 1989: Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press.

- Winter, Jay: The Great War and the British people, London 1985: Palgrave Macmillan.