Introduction↑

World War I (WWI) represents a period of particular interest for both past and present academic research thanks to the war’s unique character, which broke with earlier warfare methods and techniques. The impact of the war on both Europe and the United States are interesting areas of study, but the Austro-Hungarian monarchy is a particularly fascinating case since 1918 signalled the end of an empire that had existed for many centuries. Researchers have investigated not only the political and military performance of Austria-Hungary during WWI, but also the empire’s economic development between 1914 and 1918. Following the end of hostilities a number of Austrian studies were published, in addition to a large number under the oversight of the Carnegie Foundation. The latter were written predominantly by former high officials in the monarchy; their research was supplemented by their own personal experience during the war. The National Bureau of Economic Research also published studies by Austrian authors. After the Second World War, predominantly foreign researchers took up studies on the economic performance of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy during the First World War. In this context it should be mentioned that predominantly American authors were responsible for path-breaking research on the Austro-Hungarian economy – particularly the industrialization of the region – in both WWI and other periods.

The following study concentrates on the organization of the Austro-Hungarian war economy between 1914 and 1918. It tries to provide the relevant facts as well as an assessment based on the present state of knowledge.

Austria-Hungary’s Economic Capacity and War Effort↑

Although the Austro-Hungarian Empire was frequently regarded as a great power because of its more than 50 million inhabitants, this was by no means the case when considering the economic perspective. Compared to other European great powers like Britain, France or Germany, Austria-Hungary had limited economic resources. Low overall production levels and income were due to the high variation in economic development among the Dual Monarchy’s regions. Some regions were highly industrialized, like Bohemia, Moravia and the cities of Vienna and Budapest, whose income level corresponded more or less to Germany or France, while others had just started industrial development, like Galicia and Littoral.[1] Although Hungary had reached a higher economic level, it remained substantially lower than Central European standards. Therefore, Austria-Hungary’s gross domestic product (GDP) per capita remained significantly lower than that of the aforementioned countries. This average, which would not have mattered as much under conditions of peace, became extremely relevant in war because it represented the potential that could be used to fuel military effort. According to economist Max-Stephan Schulze’s estimates in 1913,[2] the gross domestic product per capita was roughly half of that in France and Germany and fell short even of the Italian GDP per capita. They only surpassed Russia, which had a population more than three times as big as that of Austria-Hungary.

| Real GDP

|

Real GDP per capita

|

Population

|

|

| Country | Millions of dollars (1990 prices)

|

Dollars (1990 prices)

|

In millions

|

| Austria-Hungary | 100,515

|

1,986

|

50.6

|

| France | 144,489

|

3,485

|

41.5

|

| Germany | 237,332

|

3,648

|

65.0

|

| Italy | 95,487

|

2,564

|

37.2

|

| Russia | 254,448

|

1,488

|

171.0

|

| United Kingdom | 224,618

|

4,921

|

45.6

|

Table 1: Resources of the Belligerent Countries in 1913[3]

However, there is another important fact. Although the most recent research indicates that all participants of the First World War contributed to its outbreak, it seems obvious that strong forces in Austria, especially in the form of its chief of staff, Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf (1852-1925), had pressed for years for war against Serbia. Of course not all political forces accepted this approach; especially Franz Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria-Este (1863-1914) rejected it. Be that as it may, it remains a fact that Austria-Hungary not only commanded less economic resources for a war than its adversaries, but also showed less effort to utilize them for war preparation. Its armament expenditures were the lowest of all European powers, amounting to roughly 2.5 percent of gross national product (GNP) during the decade before the war, whereas the other countries spent between 3 and 4 percent and more.

| Years | Austria-Hungary

|

France

|

Germany

|

Italy

|

Russia

|

United Kingdom

|

| |

||||||

| 1900 to 1904 | 2.6

|

4.3

|

3.8

|

3.1

|

5.0

|

5.6

|

| 1905 to 1909 | 2.5

|

4.0

|

3.9

|

2.8

|

7.4

|

3.2

|

| 1910 to 1913 | 2.8

|

4.1

|

4.2

|

3.9

|

4.5

|

3.4

|

| 1900 to 1913 | 2.6

|

4.1

|

4.0

|

3.2

|

5.7

|

4.1

|

Table 2: Defence Expenditure[4]

Organizing Production↑

Given these conditions, how did the Austro-Hungarian authorities prepare and organize economic resources for war? The legal basis was already provided in 1912 by the War Requirements Acts (Kriegsleistungsgesetze), which granted far-reaching rights to the ministry of war and army supreme command concerning economic administration. The Hungarian parliament also passed a similar law.[5] The specific prescriptions for the economy were based on the Ordinance of War Economy (Kriegswirtschaftliche Ermächtigungsverordnung) in October 1914, which was altered into a law by the newly convoked parliament in May 1917 and which gained great importance with the destruction of the Austrian democracy in 1933.

In case of war a strict regulation of foreign trade was envisaged. First, specific imports were prohibited, namely armaments and ammunition, to shelter national producers. In the course of hostilities, imports of luxury goods were forbidden to save foreign currency for more vital items. The prohibition of exports was more or less complete; even the transportation of foreign goods through the country was banned. Of course, rather quickly it turned out that these regulations were not very useful because they made it impossible to trade with neutrals and especially with Germany, which was of vital importance. As a result, these regulations had to be modified.[6]

Thanks to the legal prescriptions, the army had industrial production in its entirety at its disposal. The military administration was fully entrusted with purchasing supplies and equipment for the armed forces. This included the provision of favourable credits or subsidies for important armament firms. Already in peacetime, the administration concluded contracts with companies, requiring them to provide the army with a certain amount of products. In case of war, this could be increased by up to threefold. Regulations to stabilize product prices were foreseen. At the outbreak of the war, the above-mentioned limit for the provision of products was annulled and supplying the army became the industry’s main task.[7]

The army also predominately managed wartime economic policy. This differs from the Western powers, where the civilian administration had a far stronger position in economic affairs. The reversed position in Austria-Hungary could be viewed on the one hand as a consequence of the weak parliamentary tradition in the empire or on the other hand as a result of the fact that Austria-Hungary represented two autonomous countries when it came to economic affairs. Therefore, the army tried to remove the possibly conflicting interferences of two civilian economic administrations. Furthermore, the civilian ministries’ weak position hampered their ability to react swiftly to the new challenges of war.[8]

The critical point of production remained the provision of raw materials. Non-ferrous metals in particular were scarce from the beginning of the war. To regulate this problem the army cooperated with the ministry of commerce to establish so-called war headquarters (Kriegszentralen) for most of the industries. They were founded as private corporations and received capital from the corresponding industries and banks. Although formally private, the headquarters were practically public institutions. This nature was underscored by a profit limit of 5 percent on the invested capital and also by the fact that the ministries of war and commerce could send commissaries with veto rights to the board of directors’ meetings. The headquarters’ main task was to procure raw materials for the respective industry; the war ministry was responsible for distribution.[9]

In specific cases, additional activities were foreseen. From 1915 onwards, owners of metal stocks were obliged to register their supplies or face a penalty. The government was entitled to requisition these stocks at a fixed price. A central requisitioning committee performed this activity. The Metal Headquarters had to take over the supplies and allocate them to the factories under the army’s control.

As this method proved not to be very successful, the Metal Headquarters was then empowered to buy stocks from the public on the open market at higher prices than those paid via requisitioning. Additionally, the government tried to collect war metals from machinery and tools in non-military industries, such as the food industry, which could no longer produce because of the lack of raw materials. The collection of church bells also became notorious.

In the case of grain, a State Grain Monopoly (Kriegs-Getreideverkehrsanstalt) was established in 1915 and acted as a purely commercial enterprise. It took over the peacetime organization of grain trade, which concerned agricultural associations as well as individual traders. Together they acted as organs of the State Grain Monopoly.[10]

The cotton wool industry was of fundamental importance to the government because it provided uniforms for the wartime army of 1 million men. One-third of the raw materials had to be imported – mainly from the Balkan countries. A Cotton Wool Headquarters (Baumwollzentrale) was also established and had to take over all cotton wool and distribute it to the factories according to their productive capacity. In the course of the war, the use of raw materials for any other purpose besides the military was forbidden. From this time on, raw wool of domestic origin could be only sold to a public purchasing commission. Lastly, the cotton wool headquarters extended its control over manufactured goods.[11]

From 1916 on, the government promoted the foundation of war associations (Kriegsverbände) and economic associations (Wirtschaftsverbände), organizations similar to the headquarters. Their mandates were much more restricted than those of the headquarters, but they were responsible for advising the government and completing administrative tasks. This organization of wartime production and distribution was characterized as “self-administration”.[12]

In the course of the war, as prices lost their distributional power, authorities increasingly preferred direct rationing. The basic problem with this procedure lay in the lack of statistical data. Thus, the government had to begin every action with investigations. Data was easier to come by for metal, since nearly 85 percent of the steel production went to the war ministry; cotton, wool and other textiles were the only other group of raw materials that were relatively easy to track.

It can generally be said that in the course of the war and the increasing scarcity of raw materials, both the army and civilian authorities interfered more and more strongly in entrepreneurs’ economic decisions. Finally, on 24 March 1917 the General Commission of War and Transition Economy (Generalkommissariat für die Kriegs- und Übergangswirtschaft) was established. It sought to introduce a comprehensive regulation of the Austro-Hungarian economy. However, obviously it was too late to be successfully implemented.[13]

Labour Force↑

The outbreak of hostilities was necessarily accompanied by a sudden reduction of the male civilian labour force, which, according to the 1910 census, amounted to 8.6 million men.[14] This number was reduced by nearly one-fifth in 1914 and continued to drop throughout the war. The high number of war casualties led to additional drafting of males into the army. In 1918 the male civilian labour force was less than half of the 1913 level. This loss of workers was reinforced at the beginning of the war by the fact that the military authorities did not take into consideration the vital necessity of qualified labour for the armament industry.

| |

|

|

|

||||

| Year

|

Male

|

Female

|

Total(including prisoners of war)

|

Male

|

Female

|

Male

|

Female

|

| |

|

||||||

| 1914 | 73.7

|

101.6

|

85.7

|

75.4

|

101.8

|

71.5

|

101.3

|

| 1915 | 60.7

|

106.4

|

81.0

|

62.9

|

108.0

|

57.9

|

104.2

|

| 1916 | 55.1

|

107.5

|

81.1

|

57.2

|

109.7

|

52.3

|

104.7

|

| 1917 | 50.9

|

110.4

|

80.3

|

52.9

|

113.4

|

48.3

|

106.4

|

| 1918 | 48.6

|

112.6

|

81.0

|

50.7

|

116.7

|

45.8

|

107.4

|

Table 3: Level of Civilian Labour Force in Austria-Hungary Compared to 1913[15]

The loss of male labour could not be fully replaced by female labour, which had amounted to 5.3 million women before the war (4.3 million of whom worked in agriculture). As the participation rate in agriculture was rather high and could not be increased any further, additional labour could only be found in the urban sector. The total increase of 10 percent therefore represented a dramatic increase. For example, the rate of female membership in the General Viennese Illness Insurance of Workers was only 27.6 percent in late 1914 compared to 42.6 percent by the end of 1918. Before the war, no women worked in the Vienna streetcars, whereas in 1918 more than half of the personnel was female.[16] But as a matter of course, women could not substitute all male skilled workers, especially not in heavy industry and mines.

Prisoners of war (POWs) represented another limited possibility for filling the labour gap. POWs were actually employed based on their qualifications, with Russians predominantly in agriculture and infrastructure construction and Italians in industry. In spring 1917, 1,045,000 prisoners worked in the Dual Monarchy.[17] One significant problem arose from the permanent deterioration of the food supply, which unavoidably reduced labour productivity.

War Finance, Inflation and Price Control↑

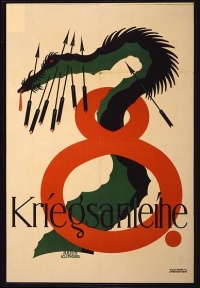

In financing the war, Austria could not rely heavily upon revenue. From 1913 to 1917/18 it raised about one-third but covered less than one-fifth of the expenses. This was due to the fact that higher taxes could both endanger production and cause discontent among the population. As a result, the government resorted to war loans and advances from the central bank. They sold eight war bonds, mainly on the domestic market, up until the end of the war. The widespread availability of these bonds did not cause a significant reduction in overall demand, because they could be presented to the central bank to obtain a loan. The central bank’s advances constituted an increasing part of the war finance. Of course, direct credits to the state were forbidden according to bank regulations, but with the outbreak of the war this part of the bank law was inhibited.

| |

|

1913

|

1917/18

|

| |

|

|

|

| Expenditure | 3,461

|

22,169

|

|

| Revenue | 3,123

|

4,194

|

|

| Deficit | 338

|

17,975

|

|

| As percent of GDP | 1.9

|

16.3

|

|

| |

|||

| Taxes | 42.1

|

45.0

|

|

| Property and income taxes | 13.8

|

16.1

|

|

| War profits tax | –

|

7.2

|

|

| Customs | 6.4

|

2.4

|

|

| Excise | 13.4

|

8.4

|

|

| Fees | 8.5

|

10.9

|

|

| Non-tax revenue | 57.9

|

55.0

|

|

| Monopolies | 13.9

|

15.5

|

|

| Commercial income | 38.7

|

37.2

|

|

| Other revenue | 5.3

|

2.3

|

|

Table 4: Austrian Government Expenditure and Revenue[18]

This resulted in a dramatic increase in the money supply, which rose from 2.19 billion crowns (Kronen) in July 1914 to 34.85 billion crowns in late October 1918. As this excessive growth of money supply met both increasing demand and decreasing supply of goods, inflation was to be expected. At the end of the war, consumer prices were about sixteen times higher than in July 1914.

In the course of the war Austria-Hungary registered a growing deficit in foreign trade. Many contemporaries regarded the deteriorating trade balance as the main reason for the Crown’s loss of purchasing power. One way to diminish the loss of foreign currency lay at first – as already mentioned – in the restriction of imports. Furthermore, the government tried to oblige importers to pay customs in gold. As this approach did not prove successful, it tried to centralize foreign exchange trade, first by a foreign currency headquarters on voluntary basis and later by creating a public body. In the end, every payment of foreign contractors had to be offered to the headquarters as well, since it provided foreign currencies for vital imports. However, even this seemingly radical solution proved to be only partially effective, leading the authorities to rely more heavily on a general import ban.[19]

Facing inflationary tendencies, the government reacted very early (August 1914) by issuing an order to provide the population with indispensable goods and threatening to punish excessive prices. This was only valid for one branch of the economy and did not represent an overall price control system. Additional regulation and new oversight boards followed with limited impact. This finally led to the empowerment of the authorities to fix maximum prices. One of the reasons why all these attempts enjoyed such limited success lay in the fact that the administration, in fixing prices, always recognized the growing costs of the intermediate products. As these were also increasing permanently due to the growing scarcity of raw materials as well as the government and national bank’s money policy, price fixing simply could not be successful. Another more technical fact should also not be overlooked. The existing bureaucracy was overburdened with the new challenges of war administration and generally unprepared to deal with economic problems. Authorities also did not dare to proceed too energetically against the black market, recognizing that this was the only way that most could survive. The authorities themselves were often responsible for attempting to stop the price increase since the war ministry did not really care about the consequences of inflation when trying to produce armament quickly and at a satisfactory quality level.

In summary, all government activities were unable to stop or retard the inflationary process during the war. There was no dammed-up inflation but an open one. It remains remarkable that in spite of all those measures, the authorities were at least able to fix prices for food rations.[20]

Transportation↑

One of the critical sectors of the Austrian war economy was transportation. In line with the initial attitude that the army be granted unlimited access to economic resources in war, the army made excessive use of the railway system during WWI. This use only increased as the Austrian general staff was forced to modify its original plans to meet unforeseen wartime transportation needs. This overuse threatened to spark a rapid breakdown in production, including of armaments. After the trade ministry protested, the military and commercial users of the transportation system made arrangements to share the railway system. However, this could not prevent the inevitable shutdown of enterprises that produced civilian goods.

In spite of the new arrangements based on a jointly designed priority system, the Austro-Hungarian railways, which was subject to military command throughout the monarchy, was marked by its inability to fully satisfy demand.[21] This meant that raw materials or food often did not reach their destination, were damaged or lost. In essence, railway traffic during the war remained under the control of railway officials, but in cooperation with the army.[22]

The difficulties for the railways started when a considerable number of its employees were enlisted to the army; this group could not be fully replaced. The troubles continued with the chronic shortage of mobile equipment (locomotives and wagon trains). This again was due to the fact that at the beginning of the war the minister of trade forbade the purchase of material abroad in order to promote national production. However, in the following years, national production facilities were never in the position to fully satisfy demand. The problems were aggravated by the loss of locomotives and carriages as a consequence of fighting and the loss of provinces like Galicia. The gain of material due to military victories obviously could not compensate the losses. The intensified use of locomotives and carriages caused a growing necessity of repair, which prevented the full utilization of available equipment. All these facts contributed to transportation difficulties not only as it related to warfare and production but also to supplying the population with vital goods.

Institutional Changes↑

All of the wartime activities described above ended with the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. Although there were certainly successor states, such as Czechoslovakia, which managed to start successfully in the post-war period,[23] the consequences of war-time economic developments proved catastrophic for the Austrian Republic – with one exception: the strengthened position of trade unions within both enterprises and society as a whole, bringing with it implications for post-war legislation.

When the armament industries were put under military control after the outbreak of the war, severe regulations for workers were introduced. They bound the workers to their workshop place and increased the number of working hours (Kriegsleistungsgesetz 1912). To ensure discipline, workers could be called up and forced to work under army regulations. In spite of this policy, unrest and strikes occurred as a result of the growing scarcity of food. Moreover, the officers in the factories realized that satisfactory labour productivity could not be gained by force, but rather required cooperation. This new approach was fostered by the union policy, which pursued cooperation with government and entrepreneurs (Burgfrieden) during the war.[24]

All that resulted in an improved position for workers and the trade unions. This became obvious as the officers in the factories frequently began to take the workers’ side in wage negotiations. Moreover, at least in the Austrian half of the monarchy, several committees were founded with equal participation of workers. This was the case with labour exchange and food rationing. At the factory level, a committee for labour complaints was created. They decided on wages and working conditions as well as the dissolution of working contracts. Finally trade unions became members in the General Commission for War and Transition Economy.[25]

These wartime changes gave workers and trade unions a new position in enterprises and society as a whole. They laid the foundation for a new political and social structure of the Austrian Republic. This found its expression not only in the strong position of the Social Democrats but in the huge collection of laws that were enacted in spite of the deplorable economic situation after the war and which provided the basis for Austrian labour law up until the present.[26]

Conclusion↑

The majority of scholars who studied the performance and organization of the Austro-Hungarian economy during World War I came to a rather critical conclusion, which is generally founded. Nevertheless, some points are in need of further discussion.

First of all, one should differentiate the Austro-Hungarian economy according to sectors and regions. It is clear that the provision of the population in the Austrian half of the monarchy with food, coal and everyday necessities broke down comparatively early, with detrimental effects on workers’ productivity. In this respect, Gusztáv Grátz and Richard Schüller’s characterization of Austria-Hungary’s breakdown as “the tragedy of exhaustion” is accurate.[27] However, the frequent military failures could in most cases not be ascribed to the insufficient provision of armaments and ammunition, but rather to the Austro-Hungarian general staff’s incompetency.[28] After initial difficulties, army provision worked quite well until the final period of the war. The production of armaments and ammunition even rose during the hostilities and reached its climax in 1916 and 1917. As the GDP shrank during the war and the provision of the civilian population broke down, it is clear that the share of armament production (as percent of GDP) increased permanently.[29]

| Available before war

|

|

|||||

| 1914

|

1915

|

1916

|

1917

|

1918

|

||

| Rifles | 2,500,000

|

149,183

|

905,832

|

1,197,117

|

1,091,117

|

237,148

|

| Machine guns | 2,761

|

1,187

|

3,730

|

6,335

|

15,436

|

12,201

|

| Guns | 2,790

|

N/A

|

1,730

|

6,948

|

7,700

|

2,064

|

| Cartridges | Million per day | 2.5

|

3.5 to 4

|

4

|

3

|

1.5 to 2

|

| Shells | Million per month | 0.3

|

1.3

|

2

|

1.4

|

0.75

|

Table 5: Production of Armament and Ammunition in Austria-Hungary[30]

Nevertheless, the impression of a complicated and insufficient organization of the war economy in Austria-Hungary arose. The first reason was undoubtedly the general expectation – not only in Austria-Hungary – that the war would not last long. Therefore, a competition among firms for war orders even arose and authorities neglected to build up stocks as long as imports were possible. The government tried to meet the necessities of war with business as usual – with the only exception being that the army had unlimited access to the country’s production and services. Only once it became clear that the war might last longer and as raw materials grew scarcer were instruments developed to meet the challenges.

The second reason for the complicated and inadequate war economy organization lay in the Austro-Hungarian authorities’ decision to adhere fundamentally to a market economy that respected the decision rights of private entrepreneurs. This attitude was reinforced by the fact that the system of private headquarters worked quite well. Only step-by-step were elements of planning and force intensified. The final approach to overall planning with the General Commission for War and Transition Economy came too late and did not satisfactorily answer the questions of who might produce what, for whom, with which materials and at what prices. Although some authors regarded the Austro-Hungarian war economy as a sort of military dictatorship,[31] it basically remained a mixed economy. It should be mentioned that the development of the war economy in the German Reich showed much resemblance to that of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy.[32]

Nevertheless, the experiences of the First World War paved the way for the overall organization of the war economy in the Second War: After 1939 it became impossible not to see World War I as a dress rehearsal for World War II.[33] These war economies were more far-reaching in their undermining of the market economy with planning, although among the Western participants, the private entrepreneur retained his function, albeit under severe state prescriptions. Looking further, these experiences provided the state with a new expertise in economic affairs. Especially the revisionist wing of the Social Democrats saw in an economy under state influence an alternative to an economy without private property or capital.

Felix Butschek, Österreichisches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung

Section Editors: Gunda Barth-Scalmani; Oswald Überegger

Notes

- ↑ Butschek, Felix: Österreichische Wirtschaftsgeschichte. Von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart, Vienna et al. 2011, p. 79.

- ↑ Schulze, Max-Stephan: Austria-Hungary’s economy in World War I, in: Broadberry, Stephen/Harrison, Mark (eds.): The Economics of World War I, Cambridge 2005, pp. 77-111.

- ↑ Schulze, Austria-Hungary’s economy 2005, p. 79.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 78.

- ↑ Kronenbitter, Günther: “Krieg im Frieden”. Die Führung der k.u.k. Armee und die Großmachtpolitik Österreich-Ungarns 1906-1914, Munich 2003, p. 228.

- ↑ Riedl, Richard: Die Industrie Österreichs während des Krieges, Vienna 1932, p. 23.

- ↑ Riedl, Die Industrie Österreichs 1932, p. 3.

- ↑ Wegs, Robert J.: Die österreichische Kriegswirtschaft 1914-1918, Vienna 1979, p. 23.

- ↑ Heller, Viktor: Government Price Fixing and Rationing in Austria during the War of 1914-18, New York 1941, p. 61.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 56.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 66.

- ↑ Riedl, Die Industrie Österreichs 1932, p. 62.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 53.

- ↑ Bolognese-Leuchtenmüller, Birgit: Bevölkerungsentwicklung und Berufsstruktur, Gesundheits- und Fürsorgewesen in Österreich 1750-1918, Vienna 1978, Table 49.

- ↑ Schulze, Austria-Hungary’s economy 2005, p. 82.

- ↑ Winkler, Wilhelm: Die Einkommensverschiebungen in Österreich während des Weltkrieges, Vienna 1930, p. 31.

- ↑ Moritz, Verena: Kriegsgefangene in Wien im 1. Weltkrieg, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigel, Andreas (eds.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Vienna 2013, p. 106.

- ↑ Winkler, Einkommensverschiebungen 1930, p. 31; Schulze, Austria-Hungary’s economy 2005, p. 98.

- ↑ Riedl, Die Industrie Österreichs 1932, p. 110.

- ↑ Heller, Government Price Fixing 1941, p. 55.

- ↑ Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie, Vienna et al. 2014, p. 155.

- ↑ Wegs, Die österreichische Kriegswirtschaft 1979, p. 108.

- ↑ Bachinger, Karl/Lacina, Vlastislav: Wirtschaftliche Ausgangsbedingungen, in: Teichova, Alice/Matis, Herbert (eds.): Österreich und die Tschechoslowakei 1918-1938. Die wirtschaftliche Neuordnung in Zentraleuropa in der Zwischenkriegszeit, Vienna 1996.

- ↑ Grandner, Margarete: Kooperative Gewerkschaftspolitik in der Kriegswirtschaft. Die freien Gewerkschaften Österreichs im ersten Weltkrieg, Vienna et al. 1992, p. 74.

- ↑ Traxler, Franz: Evolution gewerkschaftlicher Interessenvertretung. Entwicklungslogik und Organisationsdynamik gewerkschaftlichen Handelns am Beispiel Österreich, Vienna et al. 1982, p. 109.

- ↑ Butschek, Österreichische Wirtschaftsgeschichte 2011, p. 179.

- ↑ Grátz, Gusztáv/Schüller, Richard: Der wirtschaftliche Zusammenbruch Österreich-Ungarns. Die Tragödie der Erschöpfung, Vienna 1930.

- ↑ Rauchensteiner, Der Erste Weltkrieg 2014, p. 232; Wegs, Die österreichische Kriegswirtschaft 1979, p. 115.

- ↑ Assessing these facts, Table 3.9. in Schulze, Austria-Hungary’s economy 2005, p. 84 with decreasing share seems implausible.

- ↑ Wegs, Die österreichische Kriegswirtschaft 1979, p. 120.

- ↑ Teppenberg, Christoph: Totalisierung des Krieges und Militarisierung der Zivilgesellschaft, in: Pfoser/Weigel, Im Epizentrum 2013, p. 267.

- ↑ Ritschl, Albert: The Pity of Peace. Germany’s Economy of War, in: Broadberry/Harrison, Economics 2005, pp. 41-76.

- ↑ Broadberry/Harrison, Economics 2005, p. 34.

Selected Bibliography

- Augeneder, Sigrid: Arbeiterinnen im Ersten Weltkrieg. Lebens- und Arbeitsbedingungen proletarischer Frauen in Österreich, Materialien zur Arbeiterbewegung, Vienna 1987: Europaverlag.

- Bachinger, Karl / Lacina, Vlastislav: Wirtschaftliche Ausgangsbedingungen, in: Teichova, Alice / Matis, Herbert (eds.): Österreich und die Tschechoslowakei 1918-1938. Die wirtschaftliche Neuordnung in Zentraleuropa in der Zwischenkriegszeit, Vienna 1996: Böhlau, pp. 51-112.

- Broadberry, Stephen N. / Harrison, Mark (eds.): The economics of World War I, Cambridge; New York 2005: Cambridge University Press.

- Butschek, Felix: Österreichische Wirtschaftsgeschichte. Von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart, Vienna 2011: Böhlau.

- Enderle-Burcel, Gertrude: Denn Herrschaft ist im Alltag primär Verwaltung, in: Pfoser, Alfred / Weigl, Andreas (eds.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Vienna 2013: Metroverlag, pp. 274-283.

- Grandner, Margarete: Kooperative Gewerkschaftspolitik in der Kriegswirtschaft. Die freien Gewerkschaften Österreichs im ersten Weltkrieg, Vienna 1992: Böhlau.

- Grátz, Gusztáv / Schüller, Richard: Der wirtschaftliche Zusammenbruch Österreich-Ungarns. Die Tragödie der Erschöpfung, Vienna 1930: Hölder-Pichler-Tempsky.

- Heller, Viktor: Government price fixing and rationing in Austria during the war of 1914-18, New York 1941: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Kronenbitter, Günther: 'Krieg im Frieden'. Die Führung der k.u.k. Armee und die Großmachtpolitik Österreich-Ungarns 1906-1914, Munich 2003: Oldenbourg.

- Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie 1914-1918, Vienna et al. 2013: Böhlau.

- Riedl, Richard: Die Industrie Österreichs während des Krieges, Vienna; New Haven 1932: Hölder-Pichler-Tempsky; Yale University Press.

- Ritschl, Albrecht: The pity of peace. Germany’s economy at war, 1914-1918 and beyond, in: Broadberry, Stephen N. / Harrison, Mark (eds.): The economics of World War I, Cambridge; New York 2005: Cambridge University Press, pp. 41-76.

- Schulze, Max Stephan: Austria-Hungary’s economy in World War I, in: Broadberry, Stephen N. / Harrison, Mark (eds.): The economics of World War I, Cambridge; New York 2005: Cambridge University Press.

- Tepperberg, Christoph: Totalisierung des Krieges und Militarisierung der Zivilgesellschaft, in: Pfoser, Alfred / Weigl, Andreas (eds.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Vienna 2013: Metroverlag, pp. 264-273.

- Traxler, Franz: Evolution gewerkschaftlicher Interessenvertretung. Entwicklungslogik und Organisationsdynamik gewerkschaftlichen Handelns am Beispiel Österreich, Vienna; Frankfurt a. M. 1982: Braumüller; Campus Verlag.

- Wegs, J. Robert: Die österreichische Kriegswirtschaft 1914-1918, Vienna 1979: Schendl.

- Winkler, Wilhelm: Die Einkommensverschiebungen in Österreich während des Weltkrieges, Carnegie Stiftung für internationalen Frieden. Abteilung Volkswirtschaft und Geschichte. Wirtschafts- und Sozialgeschichte des Weltkriegs. Österreichische und ungarische Serie, Vienna; New Haven 1930: Hölder-Pichler-Tempsky; Yale University Press.