Introduction↑

The First World War has attracted little attention from Australian economic historians. Many of the questions about the Australian economy during the war have never been asked, let alone answered. For many years the only general work was Ernest Scott’s Australia During the War, but in recent years some of the major issues have been addressed by Ian McLean in Why Australia Prospered, The Cambridge Economic History of Australia and in Peter Yule’s contribution to The War at Home. In spite of these efforts, there has been little specialist economic analysis and many areas demand further research.

The Australian Economy in 1914↑

Following British settlement in 1788, the Australian economy developed up to 1914 as an adjunct of Britain, the world’s most successful economy, supplying a narrow range of primary products in exchange for manufactured products and capital. Within the global economic system Australia had a position that was at once privileged and precarious. As a supplier of commodities in great and increasing demand, Australia was able to maintain a high standard of living. However, its prosperity was at the mercy of overseas economic conditions. If prices fell for wool or wheat, access to markets cut, or capital inflow curtailed, then the Australian economy would suffer, as shown in the severe depression of the 1890s.[1]

The structure of exports shows the vulnerability of the economy. In 1900 wool made up 42 percent of total exports, other farm products 22 percent, base metals and coal 14 percent, and gold 12 percent. Manufactures made up less than 1 percent of total exports. Over 60 percent of Australia’s exports went to Britain.[2]

The Australian economy changed rapidly following federation in 1901. The rural economy became increasingly diversified. Wool remained dominant, but there was a rapid expansion of wheat-growing and dairying and, by 1914, the wheat industry was the country’s largest employer. The manufacturing sector grew strongly, with the number of factory workers rising from fewer than 200,000 in 1900 to over 330,000 in 1914.[3]

The Impact of War↑

The outbreak of war in August 1914 was disastrous for the Australian economy. Export industries were hit by the closing of markets and disruption of shipping, capital inflow slowed sharply, and vital imports were cut off. The impact of the war was compounded by a catastrophic drought. In the winter of 1914 the rains failed across almost all of Australia’s farmlands. Stock died by the millions and wheat production fell from 100 million bushels in 1913-1914 to less than 25 million bushels in 1914-1915 – for the first time in decades there was no exportable surplus and wheat was imported for domestic consumption. Production of wool, meat, and dairy products also fell sharply.[4]

In contrast to the Second World War, when the government established strong controls over most areas of the economy, in the First World War Australia had little in the way of formal wartime organisation of industry. Much effort was devoted to eliminating any trade with enemy countries, government-backed cartels were set up in several key industries and some superficial efforts were made to control prices, but overall there was surprisingly little government direction of industry. To a large extent government action depended on the efforts and energy of one man, William Morris Hughes (1862-1952), Attorney-General from September 1914 and Prime Minister from October 1915, but there was no great expansion of government bureaucracy to implement and oversee economic controls.[5]

Shipping↑

Since the opening of the Suez Canal and the introduction of steam ships, the cost of transport between Europe and Australia had greatly diminished, but the war once again made shipping expensive, scarce, and unreliable. Australia suffered because it took three times the shipping tonnage to move the same amount of cargo from Australia to Britain as from North America and Britain increasingly sourced supplies from North America and Argentina. Between 1913 and 1917 the tonnage of overseas shipping entering and clearing Australian ports halved.[6]

Mining↑

War and drought caused unemployment to almost double between June and December 1914, with mining districts being particularly hard hit.[7] At the outbreak of war, coal exports were banned, primarily to deny coal to the German East Asia Squadron. Although the embargo was relaxed as the threat diminished, coal exports did not recover, owing to shortage of shipping, loss of markets to other suppliers and industrial unrest on the coalfields. Domestic demand also fell due to the depressed wartime economy and the gradual shift from coal to oil as the main fuel for transport. Coal production fell from 12.5 million tons in 1913 to less than 10 million tons in 1916.[8]

The base metals industry faced an even greater crisis. Australia was a major producer of lead, zinc, and copper, but almost its entire output was sold to a German cartel which dominated world trade in base metals and also controlled much of the world’s metal processing capability.[9] At the outbreak of war, the mining companies’ best customers became enemies, their production unsaleable and their cash flows negative. Britain needed metals, but lacked the smelting and refining capacity to treat Australian concentrates. Although contracts with enemy companies were suspended at the outbreak of war, there was uncertainty as to whether they could legally be cancelled, which made it problematic to enter into new contracts.

The importance of the base metals industry forced government and industry to act. Billy Hughes, together with industry leaders William Lawrence Baillieu (1859-1936) and William Sydney Robinson (1876-1963), saw the war as an opportunity to free the Australian metals industry from German domination and develop processing capacity in Australia. Legislation was passed annulling contracts with the German cartel and a government-backed cartel of Australian base metal miners was formed. Most importantly, Hughes’ persuaded the British government to purchase at high wartime prices a large proportion of Australian lead and copper production until one year after the end of the war and the entire production of zinc for at least ten years after the war. This allowed Baillieu and Robinson to expand the Port Pirie lead smelter to be the world’s largest and build a large zinc refinery in Tasmania.[10]

Wool↑

Australian wool growers had a near monopoly of world production. Only they could supply the wool needed for clothes, uniforms, and blankets. Early in the war wool exports were embargoed except to Britain, but from early 1915 merino wool could be exported to allied countries and the United States and prices steadily increased. However, in February 1916 the British government again asked Australia to stop all wool exports except to Britain, leading to a steep fall in wool prices. After lengthy negotiations during Hughes’ visit to Britain in 1916, the British government agreed to buy Australia’s entire wool production for the remainder of the war at a price 55 percent above the pre-war average.[11]

Wheat↑

The wheat industry was more exposed than wool to the uncertainties of international markets. Whereas wool growers had the advantages of a near monopoly of world production and a product that did not deteriorate in storage, wheat growers sold a perishable product into a free world market. Further, the value of wheat per ton was significantly less than wool, so that more ships were required to shift the same value of product.

Good rains in the winter of 1915 led to a record wheat harvest in 1915-16, but the shipping shortage made the crop virtually unsaleable. By October 1915 the situation was critical and wheat growers faced ruin. Again leadership came from Billy Hughes and W. L. Baillieu. Baillieu suggested a plan under which the federal government took responsibility for receiving, storing, transporting, selling, and shipping the whole wheat crop. Within two months the necessary legislation was passed and the scheme was in operation by the beginning of 1916. Farmers were paid a government-guaranteed advance on delivery of their wheat, with the Australian Wheat Board being set up to control shipping and marketing. The scheme saved wheat growers from disaster, but the federal government was left with the problem of selling and shipping the crop. By early March 1916, over 25 million bags of wheat awaited buyers and ships.[12]

When Hughes arrived in England in March 1916, a solution for the wheat crisis was his first priority. Initially the British refused to make any concessions and Hughes responded by spending £3 million (without Parliamentary authorisation) secretly buying a fleet of tramp steamers.[13] These ships later formed the nucleus of the Australian National Line, and in the short-term helped reduce the average freight rates for Australia’s exports to reasonable levels.

The eventual salvation of Australia’s wheat industry came from reports that the 1916 North American wheat crop would fail. Faced with food shortages over the winter of 1916-1917, in November 1916 the British government agreed to buy the entire Australian wheat crop. At the time this was "the biggest wheat transaction ever recorded,” with a total price of £26,600,000. However, it soon became clear that the American crop would be quite sufficient to supply Britain and the Australian wheat was literally left to rot.[14]

By the end of 1916 the British government was committed to buying most of Australia’s wheat, wool, dairy products, meat, and metals. The scale of purchases was enormous. By the middle of 1918 the British government had paid £132 million for Australian farm products and these purchases transformed Australia’s export position from critically dangerous to relatively secure.[15]

Financing the War↑

Australia’s overall financial contribution to the Allied war effort was negative, with domestic finances being supplemented by loans and credits from Britain, but for a new nation with an undeveloped financial system it made a remarkably successful attempt to fund its war expenditure. This came at great cost, with the burden of war debts weighing down the economy throughout the interwar years.

The direct cost of the war to the Commonwealth government up to 30 June 1920 was £377 million. To give some perspective of the scale of this expenditure, in 1913-1914 the Commonwealth government raised £21.7 million in revenue and spent just £15.5 million. The expenditure on the war was vastly greater than any previous object of government expenditure in Australian history, with the sole exception of railway construction.[16]

War related expenditure peaked at about 20 percent of GDP in 1918. This was considerably less than the 38.5 percent of GDP devoted to war expenditure at the height of the Second World War, but it placed great demands on a small and unbalanced economy with an immature financial system.

Like all belligerent nations, Australia experienced severe inflation during the First World War. Estimates of the degree of inflation vary, with contemporaries believing that it was higher than later calculations suggest.[17] Wages fell far behind the rise in prices, with falling real wages being the root cause of the industrial unrest that swept Australia in the later years of the war. Public pressure forced governments to take action to control prices, but it was not decided until 1916 whether the Commonwealth had the power to regulate prices, so early action was left to the states. This action was uncoordinated and wholly ineffectual. In July 1916 the federal government set up the Necessary Commodities Commission with power to fix prices for all “food-stuffs, necessary commodities and services.” However, the commissioners realised that “during the war...prices were certain to be on the rise, and the only thing they could do was to see that profits as distinct from prices were not unduly high.”[18]

The Australian government decided in August 1914 to pay for the war primarily by printing money and borrowing rather than increasing taxation. The first war loans were raised in London, but from mid-1915 the majority of loan funds were raised in Australia. Out of war loans of £265 million to June 1919, £194 million was raised domestically. Before the war the small Australian financial market was considered incapable of mobilizing large amounts of capital, but the war loans attracted funds from many small investors as well as from the life insurance companies and banks.[19]

Although over 80 percent of Australia’s war expenditure came from borrowed money, the proportion paid from taxation revenue rose steadily as the war went on, from less than 5 percent in 1914-1915 to 25 percent in 1918-1919. In 1914-1915 the Commonwealth’s taxation revenue of £16.5 million came from just three sources, tariffs, excise, and a land tax. By 1918-1919 Commonwealth taxation revenue had doubled to £32.8 million as the result of increased excise rates and the introduction of probate duties, income tax, wartime profits tax, and an entertainments tax.[20] Of the new federal taxes, all but the wartime profits tax duplicated existing state taxes, raising issues both of double taxation and of federal-state financial relations.

Supplying the War↑

Australian manufacturing industries made only a minimal contribution to the war effort. Armaments production barely went beyond small quantities of simple artefacts such as rifles, bayonets and scabbards, while the major effort devoted to shell-making in 1915 and early 1916 was an embarrassing failure.

When the Australian colonies set up their own armed forces in the late 19th century, almost every item of equipment came from Britain. Australian manufacturing industry lacked the capability to equip or even clothe a modern military force. From the late 1880s some small steps were made, with the establishment of a cartridge factory and the growth of the textiles industry. In 1911 government-owned cordite and rifle factories were opened, followed in the next few years by a woollen mill, a clothing factory and a canvas and leather-goods factory, but these made only a small contribution to supplying the armed forces during the war.

A higher proportion of the army’s needs came from private industry, with hundreds of firms throughout Australia supplying various items. Contracts to supply the army helped sustain the economy through the downturn that followed the outbreak of the war, with the textiles, clothing, and footwear industries benefiting the most. Total Australian production was sufficient to ensure that throughout the war the army was clothed in Australian-made uniforms, shod in Australian-made shoes and slept in Australian-made blankets.[21]

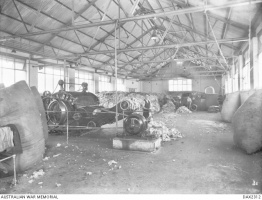

Far less successful were the efforts to produce artillery and shells. In March 1915 the government announced a plan to build a government arsenal in Canberra (then a tiny settlement far from ports and with no skilled labor force) and purchased land for this purpose. The British government refused to aid the venture with machinery or skilled workers and the plans went no further.[22] Even more farcical was a popular movement to manufacture shells in local workshops and factories around the country that began in response to the “shell crisis” following the disastrous British offensives of in the northern spring of 1915. Munitions committees were set up in every state and although the government admitted it had only the vaguest idea of what skilled labor and suitable engineering works were available, the committees pressed ahead with shell manufacture at the most amateurish level. After much effort and expense, it is estimated that only 15,000 shells of acceptable quality were made in Australia. By August 1916 the munitions factories around Australia were closing down or reverting to civilian production.[23]

Manufacturing↑

Before 1914 few manufactured products consumed in Australia were entirely made in Australia. The most substantial manufacturing industries were associated closely with primary industries, notably food processing, woollen textiles, clothing, leather, timber products, farm machinery, and mining equipment, but even these were highly dependent on imported machinery and parts. Sophisticated products such as electrical equipment, machine tools, engines, and chemical products were almost all imported, as were many of the most basic household items such as cutlery, buttons, glass, and curtains.

Manufacturers were severely affected by the cutting off of imports from enemy countries, British export embargoes on munitions-related materials (effectively all metals and machinery), and the shortage and high cost of shipping. Most suffered from shortages of raw materials, tools and components. Overall, manufacturing industry stagnated during the war. Manufacturing employment, after rising rapidly in the decade to 1914, fell slightly, and manufacturing’s share of GDP was virtually unchanged. Nonetheless, there were some significant structural developments, notably the expansion of heavy industry and the growth of import replacement industries, which laid the groundwork for the more important role of manufacturing in the Second World War and after.[24]

The Broken Hill Proprietary's (BHP) steelworks at Newcastle was already under construction when the war started, but the war made it immediately profitable and encouraged further expansion. Similarly, wartime demand for metals led to the expansion of lead smelting at Port Pirie, copper refining at Port Kembla and the construction of a zinc works at Hobart. The growth of heavy industry prompted the development of downstream import replacement industries, with new metal fabrication industries springing up around the steel works at Newcastle, the copper refinery at Port Kembla and other places.[25]

The protection from import competition provided by the war encouraged the establishment of some significant new industries. In 1917 Yarra Falls Limited became the first Australian company to manufacture fine worsted yarns on a large scale. An Adelaide carriage-making firm, Holden, began producing motor car bodies, a move seen as marking “the real birth of an Australian motor body builders’ industry.”[26] A Melbourne chemist, George Richard Nicholas (1884-1960), began making aspirin (previously imported from Germany) and his business went on in the 1920s to become a major pharmaceuticals company, successfully exporting to Britain, Europe, and Asia.[27] However, even though imports of many products were cut off during the war, the impetus to Australian production was far less than might have been expected. With the exception of the large investments in heavy industry and the downstream processing that followed, development of new manufacturing industries in the war was erratic and desultory.[28]

Conclusion↑

In stark contrast to the Second World War, when the economy grew strongly, the First World War was a major negative shock for the Australian economy. Between 1914 and 1920, real aggregate gross domestic product declined by almost 10 percent. After allowing for population growth, real incomes per capita fell by over 16 percent. As Ian McLean observes, “Had this occurred in peacetime it would have been classified as a depression.”[29]

The war left Australia heavily indebted and facing huge continuing interest payments and repatriation costs. The economy was more dependent on exports of primary products and more closely tied to the exhausted British economy than before 1914. Recovery in the 1920s was largely illusory and the economy was highly vulnerable to the fall in commodity prices that began in the late 1920s. Australia was one of the first countries to fall into depression and the downturn was both severe and long-lasting.[30]

Peter Yule, University of Melbourne

Section Editor: Peter Stanley

Notes

- ↑ Ville, Simon and Withers, Glenn (eds.): Cambridge Economic History of Australia, part three, Melbourne 2015 and McLean, Ian W.: Why Australia prospered: the shifting sources of economic growth, Princeton 2013, chapters 3-5.

- ↑ Meredith, David and Dyster, Barrie: Australia in the Global Economy, Melbourne 1999, p. 62.

- ↑ Sinclair, W. A.: Capital Formation, in: Forster, Colin (ed.): Australian Economic Development in the Twentieth Century, London and Sydney 1970; Official Year Book of the Commonwealth of Australia, 1916, p. 467.

- ↑ Connor, John/Stanley, Peter/Yule, Peter: The Centenary History of Australia and the Great War, vol. 4, The War at Home, Melbourne 2015, pp. 16-17, 35-6.

- ↑ Fitzhardinge, L. F.: The Little Digger: a political biography of William Morris Hughes, vol. II, Sydney 1979, chapter 3.

- ↑ Forster, Colin: Australian Manufacturing and the War of 1914-18, in: Economic Record 29/3 (November 1953), p. 216.

- ↑ Australian unemployment statistics in the early 20th century were based on trade union figures, which indicated a rise from 5.7 percent to 11 percent between June and December 1914. The real figures were probably higher. Official Year Book of the Commonwealth of Australia, 1916, p. 1046; Forster, Australian Unemployment 1965, p. 429.

- ↑ Scott, Ernest: Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, vol. XI, Australia during the War Sydney 1936, pp. 679-90.

- ↑ Becker, Susan: The German Metal Traders before 1914. In: Jones, Geoffrey (ed.): The Multinational Traders, London 1998.

- ↑ Yule, Peter: William Lawrence Baillieu, founder of Australia’s greatest business empire, Melbourne 2012, chapters 18-20.

- ↑ Tsokhas, K. A.: Markets, Money and Empire. The Political Economy of the Australian Wool Industry, Melbourne 1990, pp. 24-5.

- ↑ Dunsdorfs, Edgar: The Australian Wheat Growing Industry, 1788-1948, Melbourne 1956, pp. 227-9.

- ↑ Fitzhardinge, The Little Digger 1979, chapter VI.

- ↑ Connor/Stanley/Yule, The War at Home 2015, pp. 47-49.

- ↑ Scott, Australia During the War 1936, p. 539.

- ↑ Vamplew, Wray (ed.): Australians: Historical Statistics, Sydney 1987, p. 133.

- ↑ Scott, Australia During the War 1936, p. 504; Wray, Australians: Historical Statistics 1987, p. 214.

- ↑ Scott, Australia During the War 1936, pp. 645-6.

- ↑ Connor/Stanley/Yule, The War at Home 2015, pp. 60-62.

- ↑ Official Year Book of the Commonwealth of Australia, 1920, p. 756.

- ↑ Connor/Stanley/Yule, The War at Home 2015, chapter 3.

- ↑ Connor/Stanley/Yule, The War at Home 2015, pp. 21-22.

- ↑ Connor, John S.: The War Munitions Supply Company of Western Australia and the Popular Movement to Manufacture Artillery Ammunition in the British Empire in the First World War, in: Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 39/5 (2011), pp. 795-813.

- ↑ Forster, Australian Manufacturing and the War of 1914-18 1953, p. 211.

- ↑ Forster, Colin: Industrial Development in Australia, 1920-1930, Canberra 1964, pp. 122-125.

- ↑ Conlon, Robert and Perkins, John: Wheels and Deals: the Automotive Industry in Twentieth-Century Australia, Ashgate, Aldershot and Burlington 2001, p. 24.

- ↑ Connor/Stanley/Yule, The War at Home 2015, p. 55.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 56-57.

- ↑ McLean, Why Australia Prospered 2013, p. 148.

- ↑ Connor/Stanley/Yule, The War at Home, chapter 10.

Selected Bibliography

- Beaumont, Joan: Broken nation. Australians in the Great War, Crow's Nest 2013: Allen & Unwin.

- Becker, Susan: The German metal traders before 1914, in: Jones, Geoffrey (ed.): The multinational traders, London; New York 1998: Routledge, pp. 66-85.

- Commonwealth Bureau of Census and Statistics: Official year book of the Commonwealth of Australia, Melbourne 1916-1920: Government Printer.

- Conlon, Robert M. / Perkins, John: Wheels and deals. The automotive industry in twentieth-century Australia, Aldershot; Burlington 2001: Ashgate.

- Connor, John S.: The war munitions supply company of western Australia and the popular movement to manufacture artillery ammunition in the British Empire in the First World War, in: The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 39/5, 2011, pp. 795-813.

- Connor, John / Yule, Peter / Stanley, Peter: The centenary history of Australia and the Great War. The war at home, volume 4, Melbourne 2015: Oxford University Press.

- Dunsdorfs, Edgars: The Australian wheat-growing industry, 1788-1948, Melbourne 1956: Melbourne University Press.

- Fitzhardinge, L. F.: The little digger 1914-1953. William Morris Hughes. A political biography, volume 2, London 1979: Angus & Robertson.

- Forster, Colin: Australian unemployment, 1900-1940, in: Economic Record 41/95, 1965, pp. 426-450.

- Forster, Colin: Australian manufacturing and the war of 1914-18, in: Economic Record Economic Record 29/1-2, 1953, pp. 211-230.

- Forster, Colin: Industrial development in Australia, 1920-1930, Canberra 1964: Australian National University Press.

- Maclean, Ian: Why Australia prospered. The shifting sources of economic growth, Princeton 2013: Princeton University Press.

- Meredith, David / Dyster, Barrie: Australia in the global economy. Continuity and change, Cambridge; New York 1999: Cambridge University Press.

- Scott, Ernest: Official history of Australia in the war of 1914–1918. Australia during the war, volume 11, St. Lucia 1936: University of Queensland Press.

- Sinclair, W. A.: Capital formation, in: Forster, Colin (ed.): Australian economic development in the twentieth century, London 1970: Allen & Unwin, pp. 11-65.

- Tsokhas, Kosmas: Markets, money, and empire. The political economy of the Australian wool industry, Carlton; Portland 1990: Melbourne University Press.

- Vamplew, Wray (ed.): Australians. Historical statistics, Broadway 1987: Fairfax, Syme & Weldon Associates.

- Ville, Simon P. / Withers, Glenn A. (eds.): The Cambridge economic history of Australia, Port Melbourne 2015: Cambridge University Press.

- Yule, Peter: William Lawrence Baillieu. Founder of Australia's greatest business empire, Melbourne 2012: Hardie Grant Books.