Introduction↑

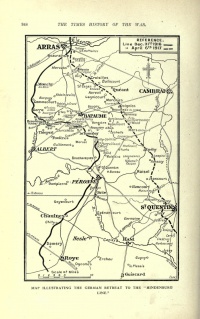

Operation Alberich took its name from the dark side of the Nibelungenlied (The Song of the Nibelungs), after the malignant dwarf who forged a magic ring of power and destruction. It was also the code name for Germany’s most important operation on the Western Front in 1917. Erich Ludendorff (1865-1937), newly placed in de facto control of the German war effort, was convinced, albeit unwillingly, that during 1917 the war on the Western Front must shift temporarily to the defensive. And that meant shortening the front to a degree as drastic as it was unprecedented.

Planning and Construction: The Great Reconfiguration↑

Preliminary planning for the Great Reconfiguration began in September 1916. The original concept involved no fewer than five interlocking defense systems extending from the Belgian coast to the Moselle Valley. Work started in October 1916 on the system perceived most crucial. The grandiloquently christened “Siegfried Line” (“Hindenburg Line” to the Allies) extended over eighty miles. The Siegfried Line was the war’s biggest military construction project. It absorbed over 500,000 tons of rocks and gravel, over 100,000 tons of cement, and 12,500 tons of barbed wire – and much of it was completed in four months.

Executing Operation Alberich↑

Construction, however, was only half of the German plan for operational withdrawal. Alberich was its complement. It was a military operation, planned in detail from the top down and methodically executed at unit level. Its intention was to destroy anything the Allies might find useful, from electric cables and water pipe to roads, bridges and entire villages. The town of Bapaume was reported as having been destroyed in forty-five minutes. It was one of more than 200 places that were completely razed to the ground.

Alberich also meant the complete evacuation of the area’s civilian population. Of these, 140,000 people classified as able to work were deported on foot or by rail to elsewhere in the French zone of occupation or to Belgium. It took 18,000 boxcars to haul away the “movable items;” miscellaneous personal and household goods. The 15,000 defined as “unfit” – the sick, the old, and the children – were evacuated separately. The Second Army headquarters at least took some pains to provide cars and ambulances, with attendants instead of guards, for the latter category of deportees. But, however they were implemented, the deportations in particular caused discomfort – even guilt. Rupprecht, Crown Prince of Bavaria (1869-1955), commanding one of Ludendorff’s army groups, compared Alberich to the devastation of the Palatinate by Louis XIV, King of France (1638-1715) in the 17th century, still a trope for evil in Germany, and did not want his name associated with it.

Conclusion↑

Alberich was a tactical success. The military withdrawal was complete in only three days. It took the Allies by surprise, delayed their advance, and it profoundly shocked not only French and British soldiers, but home fronts and neutrals. Destruction was a familiar aspect of the Great War. The Russians had devastated large swaths of their own territory in the Great Retreat of 1915, justifying it in terms of military necessity. The Germans made the same case – but that made no impression on public opinion in Allied and neutral countries alike. Alberich was executed in the heart of Europe, against what was considered civilized people. Its effects could be filmed, photographed, and reported ad infinitum. The destruction and depopulation were far in excess of obvious military requirements. They were also institutionalized, the work of detailed, systematic planning. It took little effort for Allied propagandists to present Operation Alberich as the pinnacle of “Hun barbarism”, and at Versailles, Alberich was used as a trope for legitimating and justifying claims for punitive reparations. No less than its operatic namesake, Alberich created power and destruction with long-lasting consequences.

Dennis Showalter, Colorado College

Section Editor: Mark Jones

Selected Bibliography

- Geyer, Michael: Rückzug und Zerstörung 1917, in: Hirschfeld, Gerhard / Krumeich, Gerd / Renz, Irina (eds.): Die Deutschen an der Somme 1914-1918. Krieg, Besatzung, verbrannte Erde, Essen 2006: Klartext Verlag, pp. 163-179.

- Hull, Isabel V.: Absolute destruction. Military culture and the practices of war in imperial Germany, Ithaca 2005: Cornell University Press.

- Kramer, Alan: Dynamic of destruction. Culture and mass killing in the First World War, Oxford; New York 2007: Oxford University Press.