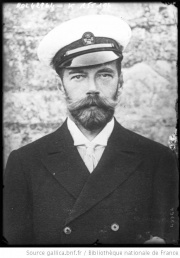

Heir to the Throne↑

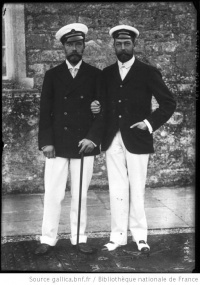

Commentators tend to depict the young Nicholas Romanov (1868-1918) as narrow in intellectual horizon and poorly prepared for power. Boris Anan’ich and Rafail Ganelin, however, offer an alternative picture of broad instruction by some outstanding individuals. Nicholas’ studies embraced natural sciences and political history, Russian literature, French, German and law. His economics teacher Nikolai Khristianovich Bunge (1823-1895), a former dean of Kiev University, had set Russia on the path of economic modernisation as Minister of Finance. Military experts provided grounding in statistics, strategy, training and technology and Nicholas experienced military life first hand in regimental camps. Dominic Lieven maintains that Nicholas was quick-witted and, although his military service was mostly dedicated to hunting and carousing, was aware of the realities of ruling Russia. He made an official tour of Europe, Asia and the farther reaches of the empire, sat on the State Council and was chair of the Special Committee to Aid the Needy during the 1891 famine and the Siberian Railroad Committee. At the time of his father’s unexpected illness, however, he was not initiated into state secrets, had scant grasp of overall policy and few close advisors, and felt utterly unprepared for the task ahead.

Autocrat and Family Man↑

In a single month in late 1894 Nicholas became ruler of a vast empire and a married man. Early biographical accounts concentrate on Nicholas the family man, emphasising his devotion to his wife, Aleksandra, Empress, consort of Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia (1872-1918), their three daughters and haemophiliac son. At their palace in Tsarskoe Selo the Tsar interspersed meetings with officials and report reading with hours taking tea, reading aloud or going for sleigh rides with his family. From the 1990s, a number of historians, including Lieven, Andrew Verner and Mark Steinberg and Vladimir Khrustalëv, have argued that the preoccupation of the intensely private Nicholas with his family and the superficiality of his diary entries with their notes on the weather should not detract from his sense of his sacred political duty as autocrat, which he retained even once forced to concede a parliament, the State Duma, in October 1905.

Tsar and Society↑

Nicholas inherited a problem facing Russian tsars since defeat in the Crimean War in 1856, the conundrum of modernisation. Maintenance of the regime’s position as a great power and its domestic prestige required economic and educational reform. Rapid industrialisation and urbanisation, however, threatened political stability as demands on government multiplied, traditional pillars of support in the peasantry and landowning gentry were weakened or alienated and groups with uncertain loyalties, from impoverished industrial workers to the intellectual, professional and commercial classes, asserted themselves. Nicholas persevered with state-led industrial development, driven by Minister of Finance until 1903 Sergei Iul’evich Vitte (1849-1915), while resisting greater public participation in government and maintaining rigid social hierarchies. His first political statement rebuked elected representatives of local councils, the zemstvos, for "senseless dreams" of involvement in government affairs. When discontent at unsuccessful international adventures or internal repression and deprivation broke out, as in 1905 following the disastrous Russo-Japanese War and the shooting of peacefully demonstrating workers on Bloody Sunday, the Tsar’s response combined limited concessions with shows of force. This contradictory reaction, in keeping with Nicholas’ archaic personal conception of the monarch as father of the Russian people, in turn firm and indulgent with his wayward children, further exacerbated popular discontent.

War Leadership↑

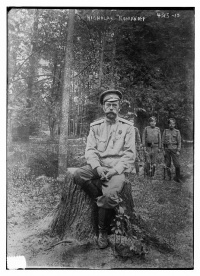

Nicholas II could be indecisive but he was resolved to defend Russia’s status on the global stage. His determination to assert Russia’s position in the Far East contributed to outbreak of war with Japan in 1904. Despite his misgivings over the conflict, he prosecuted the war tenaciously in the face of catastrophic defeats, before pursuing a settlement that saved Russia’s reputation. Likewise, while he was not an enthusiastic supporter of pan-Slavism and did not wish for war with Germany - even attempting to negotiate a secret alliance with his cousin, Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941) at Björkö in 1905 - Nicholas could not countenance further humiliation in the Balkans in 1914 by allowing Austria to annihilate Serbia. He was also committed to securing Russia’s interests in Constantinople and the Straits against German ambition. On 12 July (25 July) 1914 he inaugurated preparations for war, although he attempted to stave off hostilities in personal communications to Wilhelm II and only hesitantly gave the order for general mobilisation on 17 July (30 July). After the retreats of summer 1915 he assumed formal command of the army in defiance of ministerial objections, replacing Nikolai Nikolaevich, Grand Duke of Russia (1856-1929) as Commander-in-Chief. There were sound reasons for Nicholas’ action, aside from his notions of duty and distrust of relations between the Grand Duke and the Duma, zemstvo unions and other public bodies active in the war effort. The Grand Duke was regarded in some quarters as an incompetent general, was insensitive to civilians in regions under army control, and the lack of coordination between military and civilian authority had caused chaos. The military situation improved after the Emperor’s arrival at headquarters, culminating in a successful offensive by General Aleksei Alekseevich Brusilov (1853-1926) in summer 1916. Assumption of command, however, identified him even more closely with the human losses and economic dislocations of the war. It fostered the impression that the unpopular Empress Aleksandra, unfairly lambasted for treason on account of her German origins, was left running the country with the disreputable holy man Grigori Rasputin (1869-1916) and a succession of incompetent ministers. It also removed the Tsar from Russia’s capital, renamed Petrograd, as revolutionary unrest brewed.

Nicholas the Last↑

Revolution, Abdication, Murder↑

By February 1917, when crowds protesting about bread queues and calling for an end to the war and autocracy were joined on the streets of Petrograd by garrison soldiers, Nicholas II could not count on support from a parliament he had repeatedly prorogued. Pillars of conservatism in the nobility, army and imperial family had begun urging him to accede to demands for a government enjoying public confidence and secretly plotting for a palace coup. On 2 March (15 March) 1917 Nicholas signed an abdication manifesto in favour not of his ailing son but his brother, who, fearful of the Petrograd masses, declined the crown, ending 300 years of Romanov rule. The new Provisional Government confined Nicholas and his family to the palace at Tsarskoe Selo, in part for their own safety, moving them to Tobolsk in Siberia when armed demonstrations by workers and soldiers broke out in Petrograd in July. Following the Bolshevik revolution of October 1917 and the onset of Civil War, controls over the prisoners tightened and in April 1918, amidst rumours of monarchist plots to free them, the family was moved to the Bolshevik stronghold of Ekaterinburg. There, whether on orders from the party leadership or local initiative, they were executed.

Assessments↑

Nicholas was vilified as a bloody tyrant by the Soviet regime and romanticised as a martyr among Russian émigrés. In post-Soviet Russia he has been canonised, along with his family, by the Russian Orthodox Church. Western scholarship has been coloured by attitudes to the Bolshevik regime and its collapse and shaped by debates between those optimistic about the progress of tsarist Russia on the eve of war and those who believe it was in fundamental crisis. Those who are largely optimistic, such as Arthur Mendel, point to economic growth, the Duma, the spread of education, agricultural reforms under Prime Minister Petr Arkad’evich Stolypin (1862-1911) and an emerging middle class as indicators that Nicholas’ Russia would have evolved into a prosperous democracy had the First World War not erupted. Pessimists, like Leopold Haimson, foreground the unsustainable methods and costs of industrialisation, irreconcilable gulfs in society and weak constitutional foundations as evidence of looming disintegration. Russian domestic policy, of course, cannot be neatly separated from escalating European tensions. Nor should the role of Nicholas be reduced to misfortunate victim of events. Works by historians such as Verner and Lieven explore how the Tsar’s personality fatally exacerbated shortcomings in the autocratic system. Nicholas’ religious fatalism, aloofness, pedantry, vacillations over policy and dedication to personal rule disastrously intersected with the bureaucratic rivalries, arbitrariness and administrative overload inherent in the absolutist monarchy. Nicholas may have been better suited to the role of constitutional monarch but he clung to a system inadequately managing social and economic change and poorly coordinating the state at war.

Siobhan Peeling, University of Nottingham

Section Editors: Yulia Khmelevskaya; Katja Bruisch; Olga Nikonova; Oksana Nagornaja

Selected Bibliography

- Anan'ich, Boris V. / Ganelin, Rafail S.: Nicholas II, in: Russian Studies in History 34/3, 1995, pp. 68-95

- Haimson, Leopold: The problem of social stability in urban Russia, 1905-1917 (Part 1), in: Slavic Review 23/4, Dezember 1964, pp. 619-642, doi:10.2307/2492201.

- Haimson, Leopold: The problem of social stability in urban Russia, 1905-1917 (Part 2), in: Slavic Review 24/1, March 1965, pp. 1-22, doi:10.2307/2492986.

- Kolonit͡skiĭ, Boris: 'Tragicheskaia erotika'. Obrazy imperatorskoi sem’i v gody pervoi mirovoi voiny ('Tragic eroticism'. Images of the Imperial family during the First World War), Moscow 2010: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie.

- Lieven, Dominic C. B.: Nicholas II. Twilight of the Empire, New York 1994: St. Martin's Press.

- Slater, Wendy: The many deaths of Tsar Nicholas II. Relics, remains and the Romanovs, London 2008: Routledge.

- Steinberg, Mark D. / Khrustalëv, Vladimir M. (eds.): The fall of the Romanovs. Political dreams and personal struggles in a time of revolution, New Haven 1995: Yale University Press.

- Verner, Andrew M.: The crisis of Russian autocracy. Nicholas II and the 1905 Revolution, Princeton 1990: Princeton University Press.