Geopolitics and U.S. Dominance↑

Since the end of the 19th century, the United States had intensified their expansion through the Caribbean and Central America, establishing protectorates and intervening in the construction of the Panama Canal. When the Great War began in 1914, Nicaragua had endured two years of American military occupation. The overthrow of José Santos Zelaya’s (1853-1919) liberal government (1893-1909) by his opponents resulted in a period of political instability that led the country to seek protection from the United States, and to the subsequent military occupation between 1912 and 1925 and the conservative restoration with the administrations of Adolfo Díaz (1875-1964) from 1913-1917 and Emiliano Chamorro (1871-1966) from 1917-1921.

The dollar diplomacy in Nicaragua implemented a fundamental juridical and institutional modernization. The United States assumed the fiscal, budget and banking administration of Nicaragua, the public finances of which had been in a chronic stage since 1913. Together with the financial plan of 1917 to prevent new moratoriums in external debt, a treaty in 1914 concluded the consolidation of the American protectorate in Nicaragua. Zelaya’s intentions to negotiate the construction of an interoceanic canal with different powers and German intentions to develop that project precipitated the American arrangements that led to the signature of the Bryan-Chamorro Treaty, which gave the United States exclusive rights in any canal project. Once the Panama Canal was inaugurated in 1914, the intent of the treaty was not economic but rather strategic.

The official Nicaraguan position in the face of war was related to the American occupation. The Nicaraguan government broke relations with Germany on 8 May 1917 and declared war on the Central Powers on 18 May 1918. Although it did not send troops to Europe, the diplomatic rupture with Germany drew criticism from nationalists, liberals and opponents within Chamorro’s government. Such criticisms were raised within the National Congress and in newspapers such as La Tribuna; they pointed to the lack of national honor among conservative who had previously also signed the canal treaty.

Disorders in Commerce and Trade↑

The priorities of the European war economy caused a fall in prices and the demand for tropical products, affecting the terms of commercial exchange for all of Central America. The interruption of commercial shipping and European bank credits to Central American importers offered the United States the opportunity to strengthen its economic hegemony in the region.

The fall of imports from Europe, however, did not reinforce the local industry due to the difficulty of importing capital goods and the lack of internal demand and infrastructure. The United States supplied nearly 80 percent of imports in Nicaragua, Guatemala and Costa Rica and absorbed a large part of the Central America coffee exports, but not at the high price Europeans paid. A certain diversification in exports (coffee, bananas, metal, cattle and subsistence products) and more railway connections with the Pacific ports than countries like Honduras cushioned the commercial effects of the war in Nicaragua.

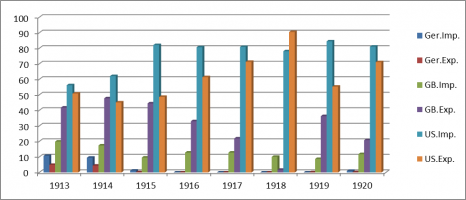

The American economic consolidation stands out in the percentages of Nicaragua’s trade involvement. As shown in the graph, the increased American involvement was remarkable between 1913 and 1920, unlike the fall of European countries’ participation. None of those European markets regained their pre-war trade involvement in Nicaragua in the 1920s (see graph).

The displacement of rival powers initiated with the diplomacy of the interoceanic canal was consolidated during the war years. German investments in Nicaragua, which reached 10 million U.S. dollars before the conflict, fell to 2.5 million in 1918. The war led to the bankruptcy of several German trade houses. Nevertheless, in some cases, they founded trade houses right in the middle of the conflict. This suggests that the war situation was not so extreme for the German community. Ex-President Chamorro confessed in his autobiography to having been elusive in executing the embargo of goods against the Germans and their allies established by the United States upon entering the war. He said he had known German businesses since the 1880s and had sympathy for their marriage ties with Nicaraguan women. He thought it improbable, as well, that the bonds with their country of origin represented a risk.[1]

Activism: Mobilization of Opinions and Identities↑

With the American entry into the conflict in April 1917, the press in both Nicaragua and the United States began reporting about German conspiracies in the Central American and Caribbean region. The New York Times published the story of a German plot to initiate a string of revolutions in the five republics and to create a United States of Central America.[2] Such a form of propaganda was combined with constant attempts to reduce the influence of the German press, which allegedly leaked military information in the news.[3] In that sense, John Barrett (1866-1938), director general of the Pan American Union, the international organization of the American republics in Washington, urged the government to create a Pan American advisory council to combat German propaganda among Latin American countries.[4] Sectors of the German community maintained an active position in the face of the conflict. German descendants went to fight in their parents’ motherland and were able to return to Managua. Others perished in battle. In addition, the German residents produced propaganda that competed with that of the Allies. The newspaper Eco Universal, which belonged to the German community, expressed its support for its country of origin during the war and countered the information disseminated by the British (Reuters) and American (Associated Press) agencies with news sent from Berlin via cable. Such publications were suspended after the rupture of diplomatic relations.

Among other social groups, the war had different meanings. The worker federations knew, through the press, of the peace claims from the European socialist groups, as well as the events that led to the October Revolution in Russia and the subsequent exit from the war. For these workers, knowledgeable of Marxist literature, the news of the Russian Revolution was cause for jubilation.

Culture: Mobilization of Sensitivities↑

The Great War represented a turn in Nicaraguan intellectual and literary work, especially for the attenuation of modernism and the hint of poetic vanguardism. When the conflict broke out, the poet Rubén Darío (1867-1916), who was then living in Europe, traveled to the American continent and, in January 1915, read his poem Pax at Columbia University in New York. He arrived in Nicaragua very ill in January 1916, where he then died. Pax, with its references to the Bible, classics and moderns, symbolized the European war with an elaborate style; the poet’s passing was an epilogue of modernism in Nicaragua.

The poet Salomón de la Selva (1893-1959), secretary and interpreter for Darío during his visit in 1915, resided in the United States and participated in the American literary environment, publishing poems and translating Hispanic poets. His attempts to enlist in 1917 in the American army were frustrated due to suspicions of anti-Americanism and, after being admitted, for refusing the requirement to adopt American citizenship and renounce his Nicaraguan citizenship. This led him to enlist with the British army, an isolated case among the Latin American writers. Some authors suggest that because of the training and transfer times, the poet’s days in the trenches in Flanders, Belgium, took place between mid-October 1918 and 11 November 1918. That short military and cultural experience was enough to produce a recognized work, El soldado desconocido (The Unknown Soldier), published in Mexico in 1922, with a humanitarian perspective close to the post-war British literature. His compassionate aesthetic and by no means epic proposal created a perception of the war experience and its horrors from an expressive economy that anticipated the Latin American poetic vanguardism.

In summary, the Great War in Nicaragua had an economic and geopolitical impact similar to its neighboring countries, consolidating U.S. dominance and occupation. However, a brief look at society reveals different actors and sociocultural events that offer a complex picture of the war and its global echoes. Hence identities, revolutionaries and poets are both local and transnational, as well as their flags and their uncanny poems.

Dennis Arias Mora, Universidad de Costa Rica

Section Editor: Frederik Schulze

Notes

- ↑ Chamorro, Emiliano: El último caudillo. Autobiografía, Managua 1983, pp. 247-248.

- ↑ German Plot Bared in Central America, The New York Times, 24 April 1917, p. 3.

- ↑ La Guerra Mundial. Informaciones peligrosas, La Tribuna, 13 July 1917, p. 1.

- ↑ Sees German Peril in Latin America, The New York Times, 30 November 1917, p. 15.

Selected Bibliography

- Bolanos, Luis: Salomón de la Selva as a soldier of the Great War, in: Hallali. Revista de Estudios Culturales sobre la Gran Guerra y el Mundo Hispánico 4, 2009.

- Chamorro, Emiliano: El último caudillo. Autobiografía, Managua 1983: Ediciones del Partido Conservador Demócrata.

- Darío, Rubén: Pax, in: Darío, Rubén: Obras completas. Lira póstuma, volume 21, Madrid 1919, pp. 1-4

- Gobat, Michel: Against the bourgeois spirit. The Nicaraguan elite under U. S. imperialism, 1910-1934, thesis, Chicago 1998: University of Chicago.

- Houwald, Götz Dieter: Los alemanes en Nicaragua, Managua 1975: Fondo de Promoción Cultural, Banco de América.

- Notten, Frank: La influencia de la Primera Guerra Mundial sobre las economías centroamericanas 1900-1929. Un enfoque desde el comercio exterior, San José 2012: CIHAC.

- Quijano, Carlos: Nicaragua. Ensayo sobre el imperialismo de los Estados Unidos, Managua 1987: Editorial Vanguardia.

- Saballos Ramírez, Marvin: Diario Eco Universal. La Primera Guerra Mundial vista por los alemanes residentes en Nicaragua, in: Revista de Temas Nicaragüenses 80, 2014, pp. 83-96.

- Saballos Ramírez, Marvin: Nicaragua y la Primera Guerra Mundial, in: Revista de Temas Nicaragüenses 75, 2014, pp. 89-101.

- Schoonover, Thomas David: Germany in Central America competitive imperialism, 1821-1929, Tuscaloosa 1998: University of Alabama Press.

- Selva, Salomón de la: El soldado desconocido, Mexico City 1922: Cultura.