Introduction↑

Music in Portugal during the First World War remains a collateral topic in the period’s historiography, which is episodically referred to in generic compendia dedicated to the history of music, encyclopaedias, and the generic scientific production on popular and erudite music, entertainment (namely musical theatre) and musical genres. It has not yet been claimed as an autonomous subject, and thus lacks a specific corpus.[1] Nevertheless, the war was a central topic for the so-called Teatro de Revista (Vaudeville theatre), the main output for musical production, a circuit that experienced some development as a business, but could not yet be considered an “industry”, given the economic and technical constraints of a Portugal that remained predominantly rural, illiterate, Catholic, and conservative, with only a meagre economic infrastructure and scarce intellectual elites.[2]

At the beginning of the 20th century, musical events were held in the intermittently open Teatro de São Carlos (National Opera House), a dozen or so privately owned small and medium-sized theatres in the main urban areas, some nightclubs,[3] and a denser, if informal, network of cafés, restaurants, community centres, popular festivities, bullfights, and other popular street celebrations. Here, an urban popular song genre that would be named fado, more so than other genres, could be heard.

During the war years, the single most important musical event in Portugal was, without a doubt, the presentation of the Sergei Diaghilev (1872-1929) company’s Ballets Russes in Lisbon, during a stopover on their way to South America (between 13 December 1917 and 3 January 1918). In March 1918, influenced by the Ballets Russes, multi-disciplinary artist José de Almada Negreiros (1893-1970), architect José “Pacheko” (1885-1934) and composer Ruy Coelho (1889-1986) created and staged a ballet, made to match Diaghilev’s company, for the benefit of the “Madrinhas de Guerra” (see Marraines de Guerre). It premiered on 11 April 1918. The war had no significant impact on musical production beyond the biographical constraints and the contact with “foreign music”. The direct relation between musical scholarly circles and the war is confined to the philosophical tale Sinfonía de Malmoral (Symphony of Malmoral) by composer Ruy Coelho[4] and some repertoire for civil wind bands (Banda Filarmónica), namely Lieutenant Francisco Pereira de Sousa’s (1885-?) symphonic poem Memória da Grande Guerra (Memory of the Great War) (1920). References to the conflict can be most easily be found in urban popular music (like fado) and repertoire specifically intended for revista.[5]

This article will focus on music production on the home front, namely for revista, and soldiers’ poetic production on the battlefield. It will end with some considerations on the aftermath of war, since the First World War resonated through the entire century in Portuguese politics and propaganda.

Propaganda, Popular Music, “Teatro de Revista”, and the Home Front↑

Although Portugal only entered the war in March 1916, the world conflict had been a topic of popular songs since 1914. One of the first references to it was the discretely patriotic meditation O Cigarro do Soldado (The Soldier’s Cigarette) from the revista Céu Azul (Blue Skies) (1914). Couplets de Palavreado (Jabbery Couplets) (O Beijo (The Kiss), 1916), and the scene Os Neutros (The Neutrals) (1916, 1916), echoed Portugal’s diplomatic indecision. Even after the German declaration of war, patriotic songs were scarce. Initially, some fado-themed newspapers promoted poetry competitions among their readers, highlighting the war’s moral imperative. These poetic productions, meant to be sung, spoke of dead comrades, the hardship of battle, and the forthcoming mobilization as an opportunity for chivalrous Portuguese soldiers to demonstrate their bravery. Such poems were not based on any concrete war experience but only on the idealization of war. After mobilization began, poems routinely invoked people and places left behind (home, mother, loved ones, the village brook), without ideological or political considerations regarding the conflict. The poems also reflected the astonishment of illiterate rural young men seeing “big cities”, trains, boats and even the sea for the first time. The machinery of war provided the token of “novelty” and “modernization”, although this was learned from the newspapers reporting from the front.

On the other hand, war was a theme that could not be avoided by revista authors. In order to attract the public to repeat performances, writers and composers constantly added new scenes and songs to the original plays, reflecting current political or social events. The conflict was a regular topic in some of the more than 110 revistas premiered during the war years, such as O Novo Mundo (The New World) (1916), Corações à larga (Hearts at Ease) (1915), Fava Rica (Dry Broad Bean) and Folha Corrida (Running Sheet) (both premiered in 1916), Lísbia Amada (Loved Lisbon) (1917), and Salada Russa (Russian Salad) (1918). 1916, by André Brun (1881-1926) – a journalist and writer serving in the Portuguese Expeditionary Corps (CEP) – was one of the very few plays whose plot revolved entirely around the war. Although it hailed the soldiers and the need to stand by Portugal’s democratic allies, it also criticized practices such as speculation and hoarding, which led to unrest, riots, and strikes.

Sometimes reference was made only to the socioeconomic impact of the conflict on daily life, such as the scarcity, rising prices and poor quality of basic products. This was evident in songs such as Fado do Seixal (Fado of Seixal), also known as Fado do Padeiro (Baker’s Fado) or Fado do Pão de Ló (Sponge Cake Fado), from Salada Russa, as well as Coro dos Géneros Alimentícios (Choir of the Foodstuffs) and Os Tubarões (The Sharks) from Chá e Torradas (Tea and Toast) (1920). Also mentioned was the new economic elite, the “novos-ricos” (new rich), whose wealth arose from monopolies on essential goods, speculation, and the development of war industries (in Salada Russa, Chá e Torradas, and Borda d’Água (Almanach Borda d’Água) (1921), among other plays). In O Conde-Barão (Count-Baron) (1918), the protagonist was an unscrupulous and opportunistic grocer who became a rich capitalist thanks to the war economy. This character, who tried and failed to copy the behaviour of the older elites, became a staple of Portuguese comic films in the 1930s and 1940s.

Some songs were recorded by actors and released by international phonographic companies (from Lindström’s group, Française du Gramophone (French Gramophone Company), Homophon/ Homokord, Pathé amongst others) as “excêntricos” (recorded comic scenes), fados, cançonetas, and couplets. These include songs like Despedida para a Guerra (Farewell to War) and O Cigarro do Soldado. Musical scores (for voice and piano) and lyrics were also published by local companies, including the well-known Fado do Expedicionário (Fado of the Expeditionary Soldier), from Dominó (1915), a score dedicated to, and in benefit of, the Red Cross Society.

Revistas were subject to wartime censorship. When O Dia de Juízo (Judgement Day) premiered in October 1915, the play had a scene about “asphyxiating gas”, which was censored in the 1918 version of the play. Nevertheless, as the war progressed, its illegitimacy, and that of war in general, emerged as a topic, in particular after the major confrontations of Portuguese soldiers on the French front.

Songs from the Battlefield↑

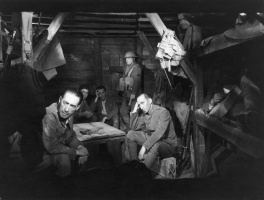

Each of the six brigades that formed the CEP had its own fanfarre[6] that stayed in the rear lines, where it performed for soldiers on Sundays. At least two programs survive in the Portuguese army archives. The performances consisted of rhapsodies of fados or well-known works for civil wind bands like Rapsódia Transmontana nº 2 (Transmontana Rhapsody nº 2), composed in 1908 by João Pinto Ribeiro (1862-?).[7] In addition, Portuguese guitars, drums, and accordions – instruments that had no place in fanfarre or civil wind bands – were brought to France by the soldiers, as is documented in various photographs.

From Pedro de Freitas’s (1894-1987) dairies[8] we learn that fado, often performed in desgarradas (sung duels), was the soldiers’ preferred musical pastime on the Western Front. Lieutenant Rogério Russo (1888-?)[9] compiled hundreds of poetic texts meant to be sung to well-known tunes from “traditional” fados and revista songs. The last section of Russo’s book is specifically dedicated to “Fado and Songs”.

While creating lyrics to be sung with “traditional” tunes is a common practice in the fado universe, some well-known revista songs, with their lyrics adapted to war topics and events, became famous among soldiers: “The Soldier’s Louse”, “Parody of the Corned-Beef (Soldier’s Louse Extract)” or “The Lice Fado” were adaptations of O Cigarro do Soldado; the Fado do Ganga (Ganga’s Fado) originated “The Ganga of the Trenches”, “Fado of Censorship”, O Cachapim (I), “Fado of the 2nd Commander”, and “Parody to the Fado do Ganga I”. Some adaptations were true successes, known throughout the CEP: Fado do Corned-Beef, Fado do Cavanço,[10] "Fado do Cachapim", and Fado das Balas e dos Ratos (Fado of Bullets and Rats).[11] None of these songs was ever recorded, but there is a minute-long sound recording made by German linguists at the Breesen prisoner-of-war (POW) camp. References to “traditional” rural melodies are rare; Russo collected a Vira (Turn) (with the lyric “The Turn in the Trenches”)[12] and Horácio Assis Gonçalves (1889-1978) remembers a Caninha Verde.[13] Russo also refers to a revista, Através da Traulitânia (Through Traulitânia) that was written at the frontline, but never staged.[14]

If the home front poetic production was timidly propagandistic, the frontline texts rarely called for national spiritual elevation (one of the few examples is the “Song of War” by António Casimiro de Carvalho, for four voices).[15] The lyrics had an individual and existential matrix. Most texts reveal a constant state of anxiety and despair among the troops, calling for courage in the face of the enemy and resignation before imminent and unexpected death in combat. Open political criticism varies between political caricature of “interventionists” (such as Jaime Leote do Rego (1867-1923), Afonso Costa (1871-1937), and Bernardino Machado (1851-1944)) to enraged criticism and a desperate call for Sidónio Pais (1872-1918), a sort of messianic redeemer, to replace the soldiers at the front with “interventionists”, criminals, fadistas (fado singers), and all the revolutionaries.[16]

Linguistic difficulties, military technology, daily work and life in the trenches or in POW camps were also regular poetic themes. Romance between Portuguese soldiers and French girls, sometimes with explicit sexual references, were also common but usually censored by the collector’s decorum, as indicated in the published texts. Some lyrics have a parodic intent and use irony to release stress from ongoing events. Mutual caricature between different army ranks was also common, usually exploring the contrast between the sacrificed soldier and the easy-living officers (represented as comfortable, safe, rested, well-dressed and well-fed). Diseases were another topic (gas-related issues, scabies, syphilis, gonorrhoea, meningitis), but psychiatric disorders (fairly common among soldiers) were never referred to.

In these poems the “soldier” is represented as innocent, laconic, illiterate, humble, romantic, but brave when necessary.[17] As its symbolic opposite, the “cachapim” (also called “folgadinho” or “easygoing”[18]), is a coward who stops at nothing to avoid labour and combat and is not above feigning illness in order to return home. Another recurrent character is the archetypical suffering mother, or the mother country calling for the supreme sacrifice. Religious metaphors and bucolic memories (villages, fields, family members, nature) are contrasted with references to war technology (Very lights, machine guns, tanks, mortars, cannons, gas, airplanes, ruins and debris), just like the wet, windy and cold climate of the Western Front is contrasted with the joyful warm Portuguese sun. References to sound are recurrent: “resounding echoes”, “explosions”, “buzzing shrapnel”, “noise”, “shaking ground”, “tremendous gunfire”, “grenades’ whistle”, and war chaos.[19] There is a quite rare poetic reference to the smells of war in “Prayer (recalling the Great Battle of 9-4-918)”: the smell of “burnt flesh” in a “frightful feast”.[20] After the Battle of the Lys, lyrics naturally dwelt on the tragic impact of the event, echoing the soldiers’ stress, horror and hopelessness in a denser narrative, full of images of dismay, unease and weariness. “If I return alive from the war” became a recurrent formulation in various texts.

Whenever possible, collectors identified the author. Given the number of texts produced, some should be noted: soldier Américo Mendes de Vasconcelos, “O Palhais” (?-1918) from the 3rd company of infantry 13 (RI13), killed near La Gorge, Corporal Sebastião Duarte,[21] medical Captain A. Casimiro de Carvalho, 2nd Lieutenants Diogo do Carmo Reis (1884?-) and Manuel dos Santos (1889-?), and Lieutenant Júlio Mesquita de Gouveia Durão (1888-1977).

Aftermath of War: Popular Music as Political Propaganda↑

In Portugal, the war induced changes in social and cultural habits. By 1918, dance halls, casinos and nightclubs were flourishing. Musical groups with jazz bands (the name used for the drum-set) played modern (American) syncopated dance rhythms like one-steps, foxtrots, or shimmies. Alongside them, theatres premiered dozens of plays. However, no poems or songs celebrating victory circulated at the war’s end. Rather, the close of the deadly conflict was celebrated through negative laments on the iniquities of war. War and its soldiers continued to be frequent themes in revistas such as Paz Armada (Armed Peace) (1919) and O Burro Em Pé (The Standing Donkey) (1920). In most of these plays, the recurring character was a fearless and rural soldier, somewhat simple but wise, good, and innocent. He was epitomized by the character “João Ratão” (John Shrew) from the revistas João Ratão (1920) and O Banzé (The Hullabaloo) (1939): a soldier that returns from France, fascinated with modernity and the lifestyle of French girls, bragging about his adventures in the trenches and arousing cowardly envy among those who had stayed behind. Hermínia Silva (1907-1993) later recorded the Fado do João Ratão (John Shrew’s Fado). João Ratão was the main character in Jorge Brum do Canto’s (1910-1994) 1940 film with the same name. The Canção do Soldado (Soldier’s Song), also known as the Fado das Trincheiras (Fado of the Trenches) came from this film. It would be used time and again until 1974 in praise of the Portuguese soldier.

Within the space of a decade, the war’s narrative would been radically reconfigured. With their innocent comic scenes, bland jokes, almost tender caricatures and mild innuendoes, revista plays gave voice to general sentiments regarding the conflict, echoing demagogic social constructions and opinions, once republican and patriotic, now populist and nationalistic. The incipient phonographic industry seized the opportunity and explored the war theme, publishing sound recordings of celebrated songs from revista but also other popular songs and fados. The song A Cruz de Guerra (War Cross) (music by Raúl Ferrão (1890-1953), lyrics by Álvaro Leal (1891-1931), recorded by Alberto Reis) is a good example which tells the story of a heroic soldier who returned decorated, but blind. More tragic was the tango O Mutilado da Guerra (The War Mutilé) (Água-pé, 1927) where another blind soldier remembers the things he can no longer see, such as his hamlet and his beloved. But there were other recorded songs and fados. A special mention should be made to the sound recording of Cruz de Guerra (War Cross) by Berta Cardoso (1911-1997), a song whose lyrics tell of the tearful mother of a soldier killed in France who reminds others that, because of her son’s valour, other mothers (presumably German) would be crying too. In brief, all songs are centred on the romanticized hero facing his tragic destiny determined by war.

Conclusion↑

In Portugal, musical production was not systematically used during the war as vehicle for propaganda because there was no clear popular adherence to the interventionist project. There was only a feeble public perception of what was at stake in the conflict because the confrontation occurred far from metropolitan Portugal, without significant civilian casualties. The only sufficiently developed business was vaudeville, or revista. Given its comic purpose, its war-related repertoire explored the caricature of facts and characters within the constraints imposed by war censorship and moral obligations towards those mobilized. This explains its characteristics – productions which exploited the public’s mainstream feelings without ever confronting them with challenging ideas, and shaping sympathetic caricatures that explored the comic and romanticism of characters (“the soldier”, “the capitalist”, etc.). Criticism, like support, was very discreet and uncompromising.

The usual practice of producing poems that would be sung with known melodies (“traditional” fados or revista songs with adapted lyrics) promoted the constitution of a very significant corpus of poetry on the front line which officials such as Russo diligently collected. Today those poems are an essential and rich resource for the perception, understanding and study of the military life of Portuguese troops on the French front.

On the other hand, characters from revista would last for decades, being used now and then, each time it was necessary to support a particular political decision, namely the neutrality during the Second World War (like the João Ratão film and its Fado das Trincheiras song) or the call for national pride and mobilization during the colonial war (1961-1975) (the same Fado das Trincheiras song). In order to reinforce its nationalist, patriotic, and conservative values, António de Oliveira Salazar’s (1889-1970) Estado Novo regime attributed the sole responsibility for the war involvement and its social and economic consequences to Afonso Costa and the First Republic. This new narrative emphasized the role of a strong and abnegated leader who would put the country’s interests first. João Ratão was a symbol of this change.

Pedro Félix, Universidade Nova de Lisboa

Selected Discography↑

Almost all recordings can be listened to at http://arquivosonoro.museudofado.pt.

A Cruz de Guerra ["War Cross"] by Alberto Reis, Clausophon Electro: P5383 / 6971, c. 1929-1931

Canção da Mariette by Estevão Amarante, Columbia: P52, 23770 / J616, c. 1940

Carta de nove de Abril by António Menano, Odeon: XXOG1039 / Lxx174801a, 1928

Carta para Maria by Carlos Lourenço, 1937

Cruz de Guerra ["War Cross"] by Berta Cardoso, Columbia: P709 / DL78, 1936

Cruz de Madeira by Alcídia Rodrigues, 1937

Despedida para a Guerra ["Farewell to War"] by Delfina Victor and Duarte Silva, Homocord: 9209, 1911

Despedida para a Guerra ["Farewell to War"] by Isabel Costa and Duarte Silva, Odeon: XO354 / 43215, n.d.

Fado das Trincheiras [Fado of the Trenches] by Fernando Farinha, Parlophone: SLME3501, 1961

Fado do Ganga ["Ganga's Fado"] by António Gomes, Victor: 72479-B, n.d.

Fado do Ganga ["Ganga's Fado"] by Domingos Barroso, Columbia: 89148 / E-9025, n.d.

Fado do Ganga nº1 ["Ganga's Fado nº1"] by Estevão Amarante, Parlophon: 158, c. 1915

Fado do João Ratão ["John Shrew’s Fado"] by Hermínia Silva, Columbia: CP967 / ML99, 1946

Fado do Pão de Ló ["Sponge Cake Fado"] by Estevão Amarante, Columbia: P46, 23570 / J617, 1926

Fado do Pão de Ló ["Sponge Cake Fado"] by Raul de Lacerda, Homokord: M9589 / P4-21211, 1926

Fado do Pão de Ló ["Sponge Cake Fado"] by Sílvio Rijo, Corona: M9589 / P4-21211, 1926

Fado do Seixal ["Fado of Seixal"] by Álvaro Barradas and Banda da Guarda Republicana de Paris, Luzofone “Idéal”: 1397, 1918

Fado Francês by Ilda Stichini, Sociedade Fabricante de Discos - Discos Simplex: 37368 / 10015, 1915

Fado Franklin by Maria Emília Ferreira, Columbia: P172, 26779 / J804, 1927

O Cigarro do Soldado ["The Soldier’s Cigarette"] by Ilda Stichini, Sociedade Fabricante de Discos - Discos Simplex: 37360 / 10036, n.d.

O Mutilado da Guerra ["The War Mutilé"] by Estevão Amarante, Odeon: Og681 / A 136317b, 1925/6?

Resposta à carta de nove de Abril by António Menano, Odeon: XXOG1084-2 / AA 174813ª, 1930

Soldado desconhecido by Ercília Costa, Odeon: XXOG1131 / 5123a, early 1930s

Selected Filmography↑

João Ratão ["John Shrew"] (Portugal, 1940, Jorge Brun do Canto)

Selected Theatography↑

A Parceria [Rodrigues, Ernesto / Bermudes, Félix / Bastos, João]: João Ratão [“John Shrew”], 1920, Teatro Avenida

A Parceria [Rodrigues, Ernesto / Bermudes, Félix / Bastos, João]: O Conde-Barão [“Count-Baron”], 1918, Teatro Politeama

A Parceria [Rodrigues, Ernesto / Bermudes, Félix / Bastos, João]: O Novo Mundo [“The New World”], 1916, Eden Teatro, Lisbon

A Parceria [Rodrigues, Ernesto / Bermudes, Félix / Bastos, João]: Salada Russa [“Russian Salad”], 1918, Teatro Politeama

A Parceria [Rodrigues, Ernesto / Bermudes, Félix / Bastos, João]: Torre de Babel [“Tower of Babel”], 1917, Teatro Apolo

Barbosa, Alberto / Pereira Coelho, José [Matos Sequeira, Gustavo de] / D'Aquino, Luiz: Dominó, 1915, Eden Teatro, Lisbon

Brun, André: 1916, 1916, Teatro Apolo

Ferreira, Lino / Rocha, Artur / Roldão, Henrique: Lísbia Amada [“Loved Lisbon”], 1917, Teatro da Trindade, Lisbon

Galhardo, Luís / Pereira Coelho, José / De Matos Sequeira, Gustavo: Céu Azul [“Blue Skies”], 1914, Teatro Avenida

Galvão, Henrique / Dias Sancho, José: Borda d’Água [“Almanach Borda d’Água”], 1921

Irmãos Unidos [Galhardo, Luis / Galhardo, José / Barbosa, Alberto / Rodrigues, Lourenço / Magalhães, Xavier de / Mourão, Carvalho]: Água-pé [“Piquette”], 1927, Teatro Avenida

Leite, Arnaldo / Barbosa, Carvalho: Chá e Torradas [“Tea and Toast”], 1920, Teatro da Trindade, Lisbon

Leite, Arnaldo / Barbosa, Carvalho: O Beijo [“The Kiss”], 1916, Teatro Nacional, Porto

Mendonça, A. / Rosendo, F. et al: Fava Rica [“Dry Broad Bean”], 1916, Teatro da Trindade, Lisbon

Ninguém, João [Barbosa, Alberto / Galhardo, José / Santana, Vasco / Vale, Amadeu do / Santos Carvalho, Miguel]: O Banzé [“The Hullabaloo”], 1939, Teatro Maria Victória, Lisbon

Rodrigues, Lourenço / Leal, Álvaro: Mulheres e Flores [“Women and Flowers”], 1928, Salão Foz, Lisbon

Roldão, Henrique / Sales, Roberto: Folha Corrida [“Running Sheet”], 1916, Teatro Apolo

Schwalbach Lucci, Eduardo: O Dia de Juízo [“Judgement Day”], 1915/1918, Teatro da Trindade, Lisbon

Torres, António / Ferreira, Fernando: Paz Armada [“Armed Peace”], 1919, Teatro da Trindade, Lisbon

Vaz, Marçal [Ferreira, Lino] / Rocha, Artur / Roldão, Henrique [Santos, Álvaro]: Corações à larga [“Hearts at Ease”], 1915, Teatro Avenida

Vaz, Marçal [Ferreira, Lino] / Magalhães, Xavier de: O Burro Em Pé [“The Standing Donkey”], 1920, Teatro Apolo

Section Editor: Filipe Ribeiro de Meneses

Notes

- ↑ See, by way of exception, Nery, Rui Vieira: Fados para a República [Fados for the Republic], Lisbon 2012, pp. 129-219; Félix, Pedro Miguel: A Business Without an Industry. The Portuguese Music Business in Turbulent Times, in: Mullen, John (ed.): Popular Song in the First World War. An International Perspective, London et al. 2019, pp. 223-241.

- ↑ Rosas, Fernando / Rollo, Maria Fernanda: História da Primeira República Portuguesa [History of the Portuguese First Republic], Lisbon 2011.

- ↑ Barros, Júlia Leitão: Os nightclubs de Lisboa nos anos 20 [Lisbon Nightclubs in the 1920s], Lisbon 1990.

- ↑ Silva Manuel Pinto Deniz: La musique a besoin d'une dictature. Musique et politique dans les premières années de l'Etat nouveau portugais (1962-1945) [Music Needs a Dictatorship. Music and Politics During the First Years of the Portuguese Estado Novo (1926-1945)], Thesis, Université de Paris 8 2011, pp. 69-71.

- ↑ Félix, Pedro: O espectáculo musico-teatral. Ensaio em dois actos com um prólogo [The Musical Theatrical Show. Essay in Two Acts With a Prologue), in: Fado e Teatro (2010), pp. 25-79.

- ↑ Sousa, Pedro Marquês de: As bandas de música na história de música em Portugal [Music Bands in the History of Music in Portugal), Porto 2017.

- ↑ Recorded by the Guarda Municipal de Lisboa for Disque Pour Gramophone, Lisbon, cat. nº 260134.

- ↑ Freitas, Pedro de: As minhas recordações da grande guerra [My Memories of the Great War], Lisbon 1935; Barrote, Susana De Brito: Pedro de Freitas. A vida e a obra de um escritor e musicógrafo nacionalista [Pedro de Freitas. Life and Works of a Nationalistic Writer and Musicologist], Salamanca 2010.

- ↑ Russo, Rogério Marques de Almeida: Arquivo poético da Grande Guerra, 1914-1918 [Poetic Archive From the Great War, 1914-1918], Porto 1920.

- ↑ Brun, André: A malta das trincheiras. Migalhas da Grande Guerra, 1917-1918 [The Men in the Trenches. Crumbs of the Great War, 1917-1918], Porto 1919, pp. 172-177.

- ↑ Freitas, As minhas recordações 1935.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 258.

- ↑ Gonçalves, Horácio de Assis: Na Ceplância. Retalhos da Grande Guerra [At CEPland. Memory Scraps of the Great War], Porto 1920, p. 217.

- ↑ Russo, Arquivo poético 1920.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 219-220.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 265-266.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 21-22.

- ↑ Brun, A Malta 1919, pp. 134-135.

- ↑ Russo, Arquivo poético 1920, pp. 86-87.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 87.

- ↑ Rita, Fernando: Com a vida tão perdida. Diário de um prisioneiro na Primeira Guerra Mundial (With Life So Lost. Diary of a Prisoner in World War I), Porto 2016.

Selected Bibliography

- Barros, Júlia Leitão de: Os nightclubs de Lisboa nos anos 20 (Lisbon nightclubs in the 1920s), Lisbon 1990: Lucifer Edições.

- Barrote, Susana De Brito: Pedro de Freitas. A vida e a obra de um escritor e musicógrafo nacionalista (Pedro de Freitas. Life and works of a nationalistic writer and musicologist), Salamanca 2010: Universidad de Salamanca.

- Brun, André: A malta das trincheiras. Migalhas da Grande Guerra, 1917-1918 (The men in the trenches. Crumbs of the Great War, 1917-1918), Porto 1983: Livraria Civilização Editora.

- Félix, Pedro: A business without an industry. The Portuguese music business in turbulent times, in: Mullen, John (ed.): Popular song in the First World War. An international perspective, London et al. 2019: Routledge, pp. 223-241.

- Félix, Pedro: O espectáculo musico-teatral. Ensaio em dois actos com um prólogo (The musical theatrical show. Essay in two acts with a prologue), in: Fado e Teatro, 2010, pp. 25-79.

- Freitas, Pedro de: As minhas recordações da Grande Guerra (My memories of the Great War), Lisbon 1935: Tipografia da Liga dos Combatentes da Grande Guerra.

- Gonçalves, Horácio de Assis: Na Ceplância. Retalhos da Grande Guerra (At CEPland. Memory scraps of the Great War), Porto 1920: Companhia Portuguesa Editora.

- Nery, Rui Vieira: Fados para a República (Fados for the republic), Lisbon 2012: Imprensa Nacional-Casa da Moeda.

- Rita, Fernando: Com a vida tão perdida. Diário de um prisioneiro na Primeira Guerra Mundial (With life so lost. Diary of a prisoner in World War I), Porto 2016: Fronteira do Caos Editores.

- Rosas, Fernando / Rollo, Maria Fernanda (eds.): História da primeira República Portuguesa (History of the Portuguese First Republic), Lisbon 2009: Ediçoes Tinta da China.

- Russo, Rogério Marques de Almeida: Arquivo poético da Grande Guerra, 1914-1918 (Poetic archive from the Great War, 1914-1918), Porto 1920: Companhis Portuguesa Editora.

- Silva, Manuel Pinto Deniz: La musique a besoin d'une dictature. Musique et politique dans les premières années de l'Etat nouveau portugais (1962-1945) (Music needs a dictatorship. Music and politics during the first years of the Portuguese Estado Novo (1926-1945)), thesis, Paris 2005: Université Paris 8.

- Sousa, Pedro Marquês de: As bandas de música na história de música em Portugal (Music bands in the history of music in Portugal), Porto 2017: Fronteira do Caos.