Occupation of Constantinople↑

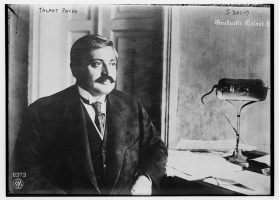

Following the capitulation of Bulgaria in late September 1918, which Talat Pasha (1874-1921) personally witnessed as he was returning from Germany, the CUP leadership resigned from the Ottoman cabinet on 8 October. The resignation was a recognition that terms of surrender in the war effort needed to be negotiated shortly and that the current leadership was in no credible position to negotiate them. While figures like Talat Pasha and Djemal Pasha (1872-1922) effectively left the stage at this point, the new grand vizier, Ahmet İzzet Pasha (1864-1937) was trusted by the CUP though he was not a member of the organization. Likewise, the cabinet and bureaucracy remained stocked with CUP figures. Armistice talks were initiated by the British General Charles Townshend (1861-1924), who had been imprisoned on the Prince’s Islands since his capture at Kut al-Amara in 1916. Ahmet İzzet Pasha’s government sent a delegation headed by Hüseyin Rauf (Orbay) (1881-1964), a senior CUP figure who had initially opposed the entry into the war on the side of Germany, to handle negotiations with the British aboard the HMS Agamemnon anchored near Mudros on the Aegean Sea. The selection of Rauf is key in that he had previously represented Turkish interests at the negotiations that resulted in the treaty of Brest-Litovsk, was not involved in the deportation and mass murder of the Empire’s Armenian subjects, and maintained close relations with figures that would ultimately plan the resistance effort under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal (1881-1938). Leading the British delegation was Admiral Somerset Gough-Calthorpe (1865-1937), commander of the Mediterranean Fleet. After the signing of the armistice, Gough-Calthorpe would be appointed the British Commissioner to the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman government agreed to demobilize and cede access to the Bosphorus Straits to British ships. A partition of the Empire would not be imposed until the conclusion of postwar treaties and until the British won agreements to allow the occupation of strategic points and the policing of areas of potential unrest. The armistice also included the surrender of prisoners of war and Armenian prisoners in Constantinople, the expulsion of German and Austrian forces from Ottoman lands, the surrender of wireless telegraph and cable stations, and a ban on coal and oil exports. The most immediate effect of the armistice was the British-led occupation of Constantinople, which informally began on 13 November 1918 and would officially begin on March 16, 1920. The occupation would extend beyond the control of military fortification to the policing of the bulk of the city against potentially rebellious supporters of the Turkish independence struggle underway in Anatolia. Constantinople would remain under Allied occupation until after the signing of the Armistice at Mudanya on 11 October 1922.

Partition of the Ottoman Empire↑

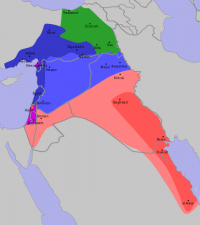

No partition was delimited by the armistice, but the occupations to come were foreshadowed by the terms agreed upon. In addition to Allied control over key points of the Trans-Caucasian railway, the Allies – mainly the British – won the surrender of all garrisons in the Hejaz, Yemen, Syria, and Mesopotamia, forces and ports in Cyrenaica and Tripolitania were to be handed over to Italy. Additionally, “in case of disorder…” the Allies reserved the right to occupy any part of the “…six Armenian vilayets” including Sis, Haçin, Zeytoun, and Aintab.[1] Remaining Ottoman statesmen and forces hoped to take advantage of Wilson’s Fourteen Points to proclaim a new nation, but plans to colonize the former Ottoman territories had been well-publicized in the last year of the war. Following the conferences in San Remo and the signing of the Treaty of Sèvres in 1920, the partition of the Arab provinces by British and French forces as well as the occupation of western Anatolia by Greece, would be formalized.

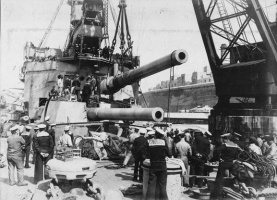

Control of the Straits↑

Seven of the first nine clauses – out of twenty-five in total – of the Armistice established Allied control of the Bosphorus Straits. The provisions included the occupation of all fortifications on the Bosphorus and Dardanelles, clearing sea mines, minefields, and torpedo tubes, the surrender of all war vessels in Turkish occupied waters, free access to all Turkish ports, and the right to occupy “any strategic points in the event of a situation arising which threatens the security of the Allies.”[2] The Straits regime would be further negotiated between the French and British at the San Remo conferences in winter 1919-1920, and a formal internationalization of the waterway and its surroundings was formalized in August 1920 with the signing of the Treaty of Sèvres.

Withdrawal from the Caucasus↑

Following the outbreak of revolution in Russia in late 1917 and prior to the final assaults by Arab and British forces in the Levant and Syria in 1918, the Ottoman army took advantage of Russian disarray to fortify Ottoman positions in the Caucasus, and to shore up good relations with Muslim forces in Azerbaijan. Following Edmund Allenby’s (1861-1936) 1918 assault in Palestine, plans for a more forceful push in the Caucasus were abandoned, and the Mudros Armistice ordered the full evacuation of Turkish troops from “North-West Persia” and “Trans-Caucasia” in addition to the Allied occupation of Batum and Baku, securing key points on the railway between those two port cities which were crucial for the transport of Caspian oil.

Treaty of Sevres (1920)↑

The San Remo conferences produced an agreement to partition the Ottoman Empire, formalized on 10 August 1920 in the Treaty of Sèvres. It left the Ottomans with a rump state across northern Anatolia, with Constantinople as its capital, and a temporary claim to Kurdish regions north of Mosul. While the Empire retained formal control over the capital city, the Straits were internationalized, and coordination between the remaining Ottoman forces now engaged in an Independence struggle in Anatolia was breaking down. Eastern Thrace and the surroundings of Izmir were ceded to Greece, the Italians were awarded a sphere of influence over Antalya and its surroundings, and an Armenian republic was created in eastern Anatolia, though none of the Allied powers were capable of defending it against Turkish forces. The treaty also formalized the mandate system in the Arab provinces, granting mandatory powers to France in Syria and Lebanon, and to the British in Transjordan, Mesopotamia as far north as Mosul, and Palestine.

Turkish War of Independence↑

The organization of a nationalist resistance under the banner of the twelfth of President Wilson’s Fourteen Points began within a month of the Mudros Armistice. From Eastern Thrace to Kars, branches of the group “Society for the Defense of Rights” (müdafaa-i hukuku milliye) were formed to promote Turkish sovereignty in the months leading up to the Greek invasion of Izmir in May 1919. In the midst of the invasion, Mustafa Kemal fled Istanbul for Samsun where he would set about coordinating resistance forces and uniting Defense of Rights Societies in successive congresses in Erzerum and Sivas. Fighting broke out first in January 1920 in the southeast region of Cilicia between Muslim-Turkish resistance fighters and French-backed Armenian groups. Fighting by regular Turkish troops would begin in September 1920, where their forces under Kâzim Karabekir (1882-1948) achieved victory over Armenian and Russian-Bolshevik troops by the end of November. Following these victories, attention would turn to the western front in 1921. The Greek army would be rebuffed in Eskişehir in January and again in April but would break through in the summer further south near Afyon. Following this defeat, Mustafa Kemal took full control of the Turkish forces, emerging victorious along the Sakarya river. After an offensive against the Greek forces, fighting would end in early September when Turkish troops entered Izmir. In October, an armistice granting control over Anatolia and Constantinople would be ceded by the Allied and Greek forces to the Turkish army led by Mustafa Kemal.

James Ryan, University of Pennsylvania

Section Editor: Erol Ülker

Notes

Selected Bibliography

- Dyer, Gwynne: The Turkish armistice of 1918. The Turkish decision for a separate peace, autumn 1918, part 1, in: Middle Eastern Studies 8/2, 1972, pp. 143-178.

- Gingeras, Ryan: Eternal dawn. Turkey in the age of Atatürk, New York 2019: Oxford University Press.

- Hurewitz, Jacob C: The Middle East and North Africa in world politics. A documentary record. British-French supremacy 1914-1945, volume 2, New Haven 1979: Yale University Press.

- Rogan, Eugene L.: The fall of the Ottomans. The Great War in the Middle East, New York 2015: Basic Books.

- Zürcher, Erik-Jan: Turkey. A modern history, New York 2004: I. B. Tauris.