Introduction↑

The Movement of National Defence was an organisation of Venizelist army officers and politicians who rose up against the royalist government in Athens in August 1916. They established a separate Provisional Government of National Defence in Thessaloniki under the leadership of ex-Prime Minister Eleutherios Venizelos (1864-1936).

The rise of the Movement↑

Venizelist army officers proceeded to set up the Provisional Government of National Defence in Thessaloniki. This was a defining moment in the development of the National Schism (Ethnikos Dihasmos) in Greece, which had begun in 1915 after Constantine I, King of Greece (1868-1923) refused to support the then Prime Minister Venizelos in his policy of entering the war to fight alongside the Entente.

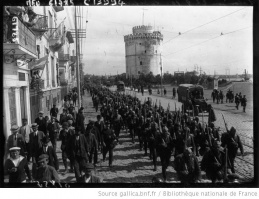

Since October 1915, Constantine had controlled the Greek government, imposing a neutralist policy, while Greek territorial integrity in Greek Macedonia was repeatedly violated by both the Allied Armée d’Orient (primarily composed of the French, the British and their colonial forces, as well as remnants of the Serbian Army and smaller Russian and Italian units) and the Bulgarian army. Furthermore, Greece’s violation of the Greek-Serbian Alliance Treaty of 1913, as well as her failure to comply with the Entente’s demands, had effectively abolished her sovereignty in Macedonia, where the presence of Serbian and Allied troops had renewed propagandist activity over the future status of the region and in particular of Thessaloniki.

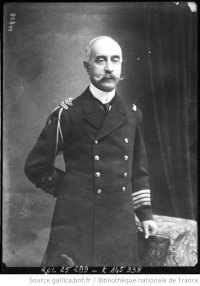

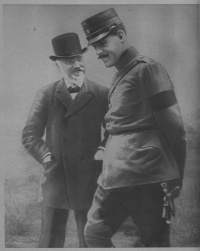

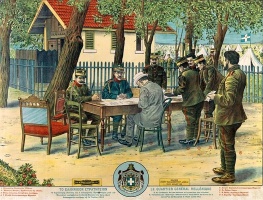

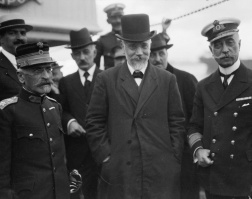

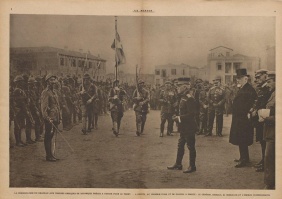

The Bulgarian advance in eastern Macedonia in May 1916 and the eventual capitulation (without any resistance) of both the Greek town of Kavalla and the Greek IV Army Corps in September 1916 outraged many Greeks, especially among the army ranks. A group of Venizelist officers decided to act immediately in order to restore Greece’s prestige and part of her sovereignty in Macedonia. On 30 August 1916 they rose up in Thessaloniki, despite Venizelos’ own reservations. After a brief clash with troops loyal to the king, they managed to take control of the city, thanks to assistance from Allied Commander in Chief Maurice Sarrail (1856-1929). Soon Venizelos, persuaded by French politicians and by Constantine’s strict adherence to his neutrality policy, decided to lead the Movement and on 26 September 1916 he formed the Provisional Government, headed by a Triumvirate (Triandria) made up of himself, General Panagiotis Danglis (1853-1924) and Admiral Pavlos Koundouriotis (1855-1935). Over the next few months and with the Allies’ help, the Provisional Government managed to take control of northern Greece, Crete and the Aegean Islands, and presented itself as an alternative to the king’s power.

National Defence’s Initiatives↑

Indeed, quite a few members of the National Defence did not conceal their antidynastic and republican leanings, causing embarrassment both to Venizelos and the Great Powers – especially Italy, Britain and, up until the February Revolution, Russia. The distribution of land and the language reforms (including the introduction of modern vernacular Greek in the primary schools, replacing the artificial, archaic Katharevousa) pushed through by the Provisional Government seemed to confirm its radical character. In order to dispel such concerns, Venizelos soon made it clear that the Movement’s objectives were to build up an army in order to recover the recently lost territories and fulfil its alliance obligations to Serbia, not to change the political regime or the monarchy. These assurances convinced the Entente to recognise the Provisional Government de facto (although not de jure) and to provide it with a loan and military material to set up an army. The Provisional Government declared war on Germany and Bulgaria on 24 November 1916, though not on Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire – in the latter case because it did not want to provoke any retaliatory or oppressive moves against the Greek population in Asia Minor.

The formation of an army that would fight alongside the Allied forces proved to be a difficult task. This was due first to the Entente’s reluctance to offer full support to the National Defence and second to a disinclination of Greek Macedonian inhabitants to enrol in the army: a sizable number were either Muslims, Jews or of Slav origin, and did not share Venizelos’ national aspirations; others remained loyal to King Constantine; and others were simply unwilling to endure the ordeal of war. Even so, by June 1917 the National Defence force numbered approximately 60,000 men and career or reserve officers. The Provisional Government of National Defence disbanded in June 1917 and Greece was reunited when Constantine was expelled by the Entente forces and Venizelos returned to power as Prime Minister. These troops participated in minor military operations until May 1918, when they played a significant role in the battle of Skra-di-Legen, and then again in September 1918 during the Allied attack that broke the Bulgarian lines and put an end to the war in the Balkans.

Loukianos Hassiotis, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki

Section Editor: Tamara Scheer

Selected Bibliography

- Kitromilides, Paschalis (ed.): Eleftherios Venizelos. The trials of statesmanship, Edinburgh 2006: Edinburgh University Press.

- Leon, George B.: Greece and the Great Powers, 1914-1917, Thessaloniki 1974: Institute for Balkan Studies.

- Mourelos, Ioannis G.: Η Προσωρινή Κυβέρνηση της Θεσσαλονίκης και οι σχέσεις της με τους Συμμάχους, 1916-1917 (The Provisional Government of Thessaloniki and its relations with the Allies, 1916-1917), in: Mnimon (Mnēmōn) 8, 1981, pp. 150-188.