Background↑

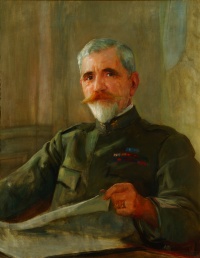

After the battle of Caporetto and the retreat to the Piave River (24 October - 9 November), the new Italian line had two pillars of defense: the Piave river and Mount Grappa, a naturally strong defensive position. Mount Grappa was defended by the 4th Army, commanded by General Mario Nicolis di Robilant (1855-1943). The retreat of the 4th Army from Cadore was difficult: near Longarone, a German unit, commanded by Lieutenant Erwin Rommel (1891-1944), surrounded the rear-guard of the 4th Army (9 November). However, most of the 4th Army reached Grappa and immediately constructed a defensive line.

Armando Diaz (1861-1928), the new chief of staff, planned the defensive battle to prevent the invasion of the Po valley. The Italian position looked weak: Diaz had only thirty-three divisions against fifty Austro-German divisions and the Italian army had lost over 3,000 pieces of artillery during the retreat. The Class of 1899, also known as “i ragazzi del ’99”, was called up early and, after rudimentary training, sent to the front. In the first days of November 1917, the Entente Commanders dispatched eleven divisions as a reserve. The Austro-Hungarian and German armies attempted to break through the front along the course of the Piave, but were unable to cross the river. General Otto von Below (1857-1944) attempted to cross the river at its highest point in the attack against Mount Grappa.

The battaglia d’arresto↑

On 13 November 1917, the army group commanded by General Alfred Krauss (1862-1938) assaulted the Grappa Massif in an attempt to proceed toward Bassano. Krauss’s army occupied Mount Perna but did not conquer the Grappa summit. General von Below ordered further attacks from the east and west, but the Austro-German troops suffered heavy losses. Despite the inexperience of the new Italian soldiers, the 4th Army defended their position. Since Below’s army was exhausted from three weeks of fighting, they couldn’t replenish their losses and build up supplies of ammunition to support the offensive. From 22 to 24 November, Austro-German troops attempted to conquer Mount Pertica, Col Caprile and Col della Beretta, but every attack was thwarted by Italian troops. In the end, Erich Ludendorff (1865-1937), worried by the British attack at Cambrai, asked for the cessation of fighting in Italy. On 26 November, the operation on the Italian front was suspended.[1]

On 11 December, Austro-German troops launched a new audacious offensive against Italian positions on Grappa and Asiago Plateau. They conquered Valderoa and Mount Asolone and could have advanced toward Bassano, but no further progress was made. Furthermore, the Allied reinforcements came into line. On 20 December, the front was covered by snow and it was difficult to continue the offensive. On 21 December, the Habsburg High Command ordered the suspension of the attack and the XIV German Army was transferred to the Western Front. Austro-German generals underestimated the resistance the Italian army could mount. Furthermore, Di Robilant adopted an elastic defence tactic: instead of defending sectors that were in greater difficulty, they would be left to the enemy to be reconquered later by rapid counterattacks. Finally, the Italian High Command decided to concede more autonomy to the officers, increasing morale as a result.[2]

Consequences and the myth of Mount Grappa↑

Owing to the defeat of the Austro-German offensive on Mount Grappa, this battle marked a turning point in the war. The new front was shorter and easier to defend for the Italian army. Diaz had the opportunity to reorganize and re-equip the Regio Esercito. As a result of these efforts and increased rations and pay, morale and discipline were restored. During the winter, the Italians reinforced their positions. Austria-Hungary failed to turn Caporetto’s triumph into a final victory. In the first month of 1918, the Habsburg Empire began to suffer severe civilian hardship and deterioration of morale. After the battle of Mount Grappa, General Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf (1852-1925), Austrian chief of staff, wrote to his wife: “We can no longer count on victory in Italy”.[3]

The threat of the invasion gave a new and more concrete sense to the war in Italy. The war was now fought in a different spirit by Italian soldiers and was supported more strongly by the home front, although support for the war remained moderate among the rural population and the working class.[4] The battaglia d'arresto on Mount Grappa rapidly became mythologized along with the new defensive war for the survival of the homeland, which unified the Italian political forces. The socialist deputy Filippo Turati (1857-1932) proclaimed in a parliamentary speech: "Grappa è la patria".[5] The image of Mount Grappa as the last bastion of the nation began to spread via propaganda and the Italian press sacralised the battaglia d'arresto with articles and images celebrating the heroic resistance of Italian battalions. The cover of the journal «Domenica del Corriere» published a drawing of an Alpine battalion that defended its position by throwing stones against the attackers because the ammunition was finished.[6] In August 1918, General Emilio De Bono (1866-1944) wrote The song of the Grappa, which started with the phrase “Mount Grappa, you are my Homeland!”.[7] Constructed on Mount Grappa in 1901, the Chapel of Mary, Redeemer of Christians, with a statue of the Madonna (seriously damaged by the Austro-German artillery in January 1918), symbolically unified the religious cult and the national myth. Following the war, in 1922 an act by the Italian government declared Mount Grappa sacred and immortal to the Fatherland.[8] In 1935, after a dispute with the Church, the Fascist regime built a military memorial monument on Mount Grappa, turning it into a destination for patriotic pilgrimages.[9]

Francesco Cutolo, Scuola Normale Superiore, Pisa

Section Editor: Marco Mondini

Notes

- ↑ Ceschin, Daniele: L' Italia del Piave. L'ultimo anno della Grande Guerra, Rome 2017, pp. 48-50.

- ↑ Massignani, Alessandro: Monte Grappa, in: Isnenghi, Mario (ed.): Gli italiani in guerra. Conflitti, identità, memorie dal Risorgimento ai nostri giorni. La Grande Guerra. Dall’Intervento alla 'vittoria mutilata', volume 3, number 2, Turin 2008, p. 761.

- ↑ Gooch, John: The Italian Army and the First World War, Cambridge 2014, p. 282, p. 262.

- ↑ Cf. Gibelli, Antonio: La Grande Guerra degli Italiani, Bergamo 2003, pp. 302-305.

- ↑ Filippo, Turati: Parliamentary speech, in Atti parlamentari, Legislatura XXIV, I Sessione, Discussioni, Tornata del 23 febbraio 1918, p. 16095.

- ↑ Cf. Mondini, Marco: Alpini. Parole e immagini di un mito guerriero, Bari 2008, p. 70.

- ↑ Cf. Pivato, Stefano: Bella ciao. Canto e politica nella storia d'Italia, Bari 2015: Laterza, p. 154-155.

- ↑ Cf. Zaffonato, Andrea: In queste montagne altissime della patria. Le Alpi nelle testimonianze dei combattenti del primo conflitto mondiale, Milano 2016, p. 268.

- ↑ Cf. Mondini Marco: La guerra italiana. Partire, raccontare, tornare, 1914-1918, Bologna 2014, pp. 352-354.

Selected Bibliography

- Beccherle, Maurizio / Pozzato, Paolo: Quell'ultimo monte. La prima difesa del Grappa e Bassano 1915-1917, Bassano 2002: Itinera Progetti.

- Cappellano, Filippo / Di Martino, Basilio: Un esercito forgiato nelle trincee. L'evoluzione tattica dell'esercito italiano nella Grande Guerra, Udine 2008: Gaspari.

- Ceschin, Daniele: L'Italia del Piave. L'ultimo anno della Grande Guerra, Rome 2017: Salerno Editrice.

- Gooch, John: The Italian army and the First World War, Cambridge 2014: Cambridge University Press.

- Herwig, Holger H.: The First World War. Germany and Austria-Hungary, 1914-1918, London; New York 1997: Arnold; St. Martin's Press.

- Isnenghi, Mario / Rochat, Giorgio: La grande guerra, 1914-1918 (3 ed.), Bologna 2008: Il Mulino.

- Massignani, Alessandro: Monte Grappa, in: Isnenghi, Mario (ed.): Gli italiani in guerra. Conflitti, identita, memorie dal Risorgimento ai nostri giorni. La Grande Guerra. Dall’Intervento alla 'vittoria mutilata', volume 3, number 2, Turin 2008: UTET, pp. 760-771.

- Minniti, Fortunato: Il Piave, Bologna 2000: Il Mulino.

- Mondini, Marco: La guerra italiana. Partire, raccontare, tornare, 1914-18, Bologna 2014: Il Mulino.

- Vanzetto, Livio: Monte Grappa, in: Isnenghi, Mario / Alessandrone Perona, Ersilia (eds.): I luoghi della memoria. Simboli e miti dell’Italia unita, Rome 1996: Laterza, pp. 361-374.

- Zaffonato, Andrea: 'In queste montagne altissime della Patria.' Le Alpi nelle testimonianze dei combattenti del primo conflitto mondiale, Milan 2017: Franco Angeli.