Italian Military Volunteers in France↑

The history of Italian military volunteers in the First World War begins before Italy’s entrance into the war in May 1915. Starting on 3 August 1914, about 8,000 Italians living in France requested to join the French army. Of these, 5,000 were accepted and joined the Armée in summer 1914. For the most part these men served in the Légion étrangère. Additionally, roughly 700 Italians joined the Légion Garibaldienne (4th Foreign “March” Regiment), and 200 joined the Légion républicaine of Nice. (The latter group was never integrated into the French army as a whole, and eventually half of them joined the Légion Garibaldienne while the other half returned to Italy).

The story of the Italian military volunteers in France quickly became legend. According to contemporary mythical accounts, these Garibaldiens of 1914, ready for “sacrifice” and “martyrdom”, crossed the Alps in order to fight for France, “this cradle of European civilization”. Some scholars have recently brought the story of these Italian military volunteers back from myth to history. For the most part they were Italian emigrants working in France (in the Légion Garibaldienne, only 734 men out of 3,220 came from the Peninsula). Moreover, the act of joining the Légion étrangère was more closely related to workplace preservation and social integration than to the idealistic desire to fight on behalf of “oppressed” peoples. The men who came from Italy – fewer than 1,000 – were the exception.

The legions drew men with varying political beliefs. Within the ranks of the Légion Garibaldienne were libertarians, republicans, and revolutionary syndicalists. In contrast, the Légion républicaine of Nice (also known as “Compagnia Mazzini”) was almost entirely composed of members of the PRI (Partito Repubblicano Italiano) who hailed from Emilia-Romagna, Marche and Umbria. Even the objectives of the two legions were different. The Légion Garibaldienne intended to push the Kingdom of Italy to enter the war, while the republicans of the Mazzini Company wanted to distinguish themselves from the monarchy. Led by Giuseppe Garibaldi’s (1807-1882) grandson, Giuseppe Garibaldi II (1879-1950), also known as Peppino, the eldest son of Ricciotti Garibaldi (1847-1924), the Légion Garibaldienne fought on the Argonne front from December 1914 to January 1915. This is where Peppino’s brothers, Bruno Garibaldi (1890-1914) and Costante Garibaldi (1892-1915), met their deaths. From that moment on, they were seen as icons of Italian interventionism.

The Irredentist Volunteers from Austria-Hungary↑

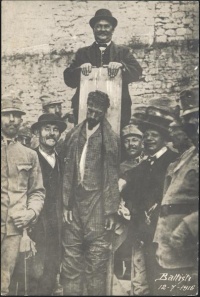

The history of the Italian military volunteers in the First World War not only consists of Italian volunteers going to fight abroad, but also of foreign volunteers coming to Italy fight. Those who came to Italy were mainly the Italian irredentists from the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It has been calculated that these volunteers numbered between 2,500 and 2,700, including more than 800 men from Trentino. Since about 60,000 men from the region fought among the ranks of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, less than one in 600 chose to join the Italian army. Although the number of volunteers is small, it is significant that it was even that high, since choosing to cross the border to join the Italian army meant running the risk of being sentenced to death for treason if captured by the enemy. This is what happened to Damiano Chiesa (1894-1916), Cesare Battisti (1875-1916), Fabio Filzi (1884-1916) and Nazario Sauro (1880-1916) during the spring and summer of 1916. Their executions marked a turning point in the public perception of the irredentist volunteers from Austria-Hungary, with the four “martyrdoms” (in particular, the hanging of Cesare Battisti in July 1916) becoming symbols of Austrian barbarity.

Volunteers during General Mobilization↑

As a consequence of Italy’s general mobilization, men between the ages of eighteen and forty were mobilized. Thus, it was only possible for those aged seventeen or over forty to volunteer, rather than be drafted into the army. From the onset of war, however, Italian military authorities also attributed volunteer status to those who joined before their age class was mobilized. Using these criteria, in 1927 the Minister of War Statistical Office counted 8,171 volunteers in 1915; according to figures provided by some historians, there were about 10,000 between 1915 and 1918. Anticipating being drafted, however, was not the only way to volunteer to go to the front. In fact, it was also possible to request a change of unit in the event of being posted far from the frontline. Consequently, over the last ten years historians have started to talk about a “subjective military voluntarism”, in an attempt not to reduce the historiographical definition of military voluntarism to the official definition provided by the Ministry of War.

The War Experience of Italian Military Volunteers↑

What drove about 10,000 Italians to choose to fight without (or before) being drafted? Beyond individual political beliefs (right or left interventionism, irredentism, anarchism), their decisions often rested on the belief that it would be morally unacceptable not to shed blood for their country – a view nationalist speakers had been preaching since the first half of the 19th century. Moreover, for most of these individuals the war constituted the chance to participate in a huge historical event that they had long dreamed about. It also gave them the opportunity to go beyond, to paraphrase their thinking, the petty ordinary life of the Giolittian Italietta. Across Europe, the war experience was characterized by an enormous gulf between the imaginary and the real. The Italian military volunteers (much as other European volunteers) experienced it in a contradictory way. The war they volunteered for was the heroic battle for the Grande Italia. The war they fought turned out to be an unintelligible struggle for a few meters.

How, then, did Italian military volunteers respond to this apparent lack of sense in the war? As paradoxical as it may seem, they did so by giving meaning to it. Renouncing reason was thus the first sacrifice that their country requested. By renouncing their understanding of the stakes of war, the Italian military volunteers could share the experience of being a soldier with the millions of men fighting – in Italy as well as on other European fronts – without knowing the reasons for it.

Sante Lesti, Scuola Normale Superiore

Section Editor: Marco Mondini

Selected Bibliography

- Cecchinato, Eva: Sotto l'uniforme. I volontari nella Grande Guerra, in: Isnenghi, Mario / Ceschin, Daniele (eds.): La Grande Guerra. Dall’intervento alla vittoria mutilata, volume 1, Turin 2008: Utet, pp. 176-186.

- Dogliani, Patrizia / Pécout, Gilles / Quercioli, Alessio: La scelta della patria. Giovani volontari nella Grande Guerra, Rovereto 2006: Museo storico italiano della guerra.

- Heyriès, Hubert: Les Garibaldiens de 14. Splendeurs et misères des chemises rouges en France de la grande guerre à la seconde guerre mondiale, Nice 2005: Serre éd..

- Prezioso, Stéfanie: Les Italiens en France au prisme de l’engagement volontaire. Les raisons de l’enrôlement dans la Grande Guerre (1914-1915), in: Cahiers de la Méditerranée 81, 2010, pp. 147-163.

- Zadra, Camillo / Rasera, Fabrizio (eds.): Volontari italiani nella Grande Guerra, Rovereto 2008: Museo storico italiano della guerra.