Introduction↑

The history of the Spanish army between 1914 and 1918 was marked by two key circumstances: military weakness and strategic insecurity. These factors were closely interrelated. The poor conditions of the military forces were a consequence of structural deficiencies and the military and moral defeat of 1898. The precarious neutrality that Spain maintained during the world conflict was provoked by the situation of defencelessness and dependence on the main European powers.

Spanish Army↑

The Spanish Army by 1914↑

The situation of the Spanish armed forces by 1914 was largely a product of defeat in the 1898 war with the United States. Not only did the fighting against pro-independence rebels in Cuba since 1895 cost enormous military resources, but also the old Spanish Caribbean fleet was entirely destroyed by the American warships at the Battle of Santiago de Cuba. This confrontation ended the war and decided the fate of the last Spanish colonial possessions in Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines, which were put under American control by the Treaty of Paris. Therefore, while the main European powers reached the climax of their imperial domination over the world, and naval supremacy became the epitome of world-wide influence,[1] Spain with its ruined fleet was reduced to a second-rank country in the international system. There were no successful plans to reconstruct the navy until the Plan de Escuadra of 1908, and then Spain was highly dependent on foreign technology and industry.[2] The echoes of the national humiliation of 1898 still resonated with the Spanish army fifteen years later, when the tensions of the alliances system in the European continent exploded into the First World War.

The subordinate role Spain played in the Moroccan crises of 1904-06 clearly shows the extent to which the defeat of 1898 had reduced Spain to a marginal actor on the European and colonial strategic chessboard. The “disaster” of 1898 pushed a number of Spanish intellectuals such as Joaquín Costa (1846-1911) to seek new spaces for the country’s economic expansion – its “civilizing mission” – in North Africa. However, Spanish influence in the Moroccan coast was reduced to a few enclaves such as Ceuta and Melilla.[3] Spanish colonialism in Morocco soon became subordinate to the interests of the main European powers, particularly France, Britain and, to a certain degree, Germany. The Entente Cordiale between France and Britain in 1904, British possession of Gibraltar – the Western key to the Mediterranean – and French expansion over North Africa pushed the Germans to intervene in the colonial scramble for Morocco by making the case for an independent sultanate. The Germans wanted to prevent the Entente’s complete domination of the entry points to the Mediterranean. Tensions between the European powers preceded diplomatic negotiations in the Algeciras Conference in 1906, when Spain acquired the obligation of establishing a Protectorate (zone of influence) in the northern part of Morocco. France remained in control of the south. This division satisfied all parties, and implied leaving a small but strategically relevant northern zone of the Protectorate in the hands of a weak power.

Soon, the zone of Spanish influence in Morocco became a military problem. The tribes of the Rif rebelled against the Spanish colonizers. In Spain, the colonial enterprise was highly unpopular, particularly because the recruiting system was unfair: only those families unable to pay for an exemption ended up sending their sons into military service – an injustice only partially resolved by new recruiting regulations in 1911-1912. This was the reason why in 1909, the escalation of Spanish military involvement in Morocco sparked the “Tragic Week” uprising in Barcelona. Popular resistance did not stop military operations in Morocco, conducted to placate native resistance. Since 1913, El Raisuli (1871-1925) led the Berber guerrillas. Meanwhile, civilian affairs in the Protectorate came under direct military supervision. Military commanders such as General José Marina Vega (1850-1926) were appointed to the position of High Commissioner of Spain in Morocco. The problem of controlling the region of the Rif became a quagmire for the Spanish army in the years preceding the First World War.

In this period, the Spanish army was in urgent need of a structural reform. As a consequence of the incorporation of former Carlist officers into the regular army after the civil wars of the 19th century, there was an excessive number of officers. In this situation, many officers had no assignment and therefore idled away their days in desk-based jobs. To make matters worse, the officers’ salaries absorbed the greatest portion of the military budget, thus forestalling the modernization of equipment and training. As Álvaro de Figueroa, Count of Romanones (1863-1950) put it during a Congress session in November 1915: the Spanish military budget was the least efficient of all budgets known. Maintaining an army of 140,000 men cost the state the amount of 300 million pesetas. However, this money was not spent in equipment or military actions; it was mostly spent in the generals’ and officers’ salaries, as well as in “luxurious” military bureaucracy.[4] The war situation in Morocco only aggravated this defect, because in this battleground officers were able to rapidly obtain promotions based on war merits, regardless of their true abilities for command. In turn, in the peninsula, rank promotions based on seniority did not mean better professional competence. Furthermore, the social structure of the army was highly hierarchical: generals received a basic annual pay which was between ten and thirty times bigger than that of the lower-ranked officers.[5] Yet, both higher- and lower-rank officers showcased an exaggerated sense of honour – probably exacerbated after the humiliation of 1898 – which made them react virulently against any political challenge they considered as anti-patriotic. Last but not least, there was a long tradition of military intervention in Spanish politics;[6] officers understood themselves as arbiters and guarantors of the liberal system, while harbouring increasingly hostile feelings against politicians and civilians. The badly needed military reform became one of the most controversial political issues, which was even more pressing after the outbreak of the First World War.

During the First World War, Spain was deeply divided between pro-German and pro-Allied opinion groups. The Spanish officer corps was sympathetic to the Germans, since many officers admired the Prussian army model. The most influential journal for military affairs, La Correspondencia Militar, clearly adopted a pro-German stance. French policy in Morocco was bitterly criticized, and army leaders discussed plans for a hypothetical war against France.[7] British control of Gibraltar was also resented by the Spanish military officers. The army was far from being united, though. It was increasingly divided into Africanistas and peninsulares. This cleavage was of a professional rather than political kind. The Africanistas were a caste of war-experienced soldiers that had attained higher ranks thanks to their combat merits in the Protectorate. The peninsulares were opposed to this kind of promotions and soon started defending their interests by creating union councils – the so-called juntas.

The Military Crisis of 1917↑

The history of the Spanish army during the First World War was marked by the military crisis of 1917 and the Juntas de Defensa movement.[8] Structural deficiencies of the army and the wider international context were the backdrop of this crisis. Spanish officers in the peninsula, particularly junior officers, resented their bleak professional situation and the prevailing system of promotion based on war merits. Service in the dirty, undeclared war of Morocco led to astonishingly rapid promotions, as in the case of Francisco Franco (1892-1975) – promoted to the rank of major when he was only twenty-three. In contrast, officers in the peninsula faced a slow and mediocre career. From the different military academies, infantry officers felt the most aggrieved. Artillerists and Engineers, thanks to their specialized duties and privileges, enjoyed better standards. As inflation mounted and the cost of living increased during the years of the First World War, peninsula-based officers grew unhappy with the government. In Barcelona in 1916, infantry officers were the first in meeting and creating Juntas de Defensa to discuss their grievances and defend their interests. As the military movement expanded and disseminated in 1917, a political struggle between the government and the Juntas started. The junteros proved remarkably resilient in the face of the Ministry of War’s pressure to dissolve them. In fact, the military crisis was one of the reasons that forced Romanones’ government to resign, leaving the problem in the hands of subsequent governments headed by Manuel García Prieto (1859-1938) and Eduardo Dato (1856-1921). Between the spring of 1917 and early 1918, four subsequent War Ministers, Francisco Aguilera (1856-1931), Fernando Primo de Rivera (1831-1921), José Marina Vega, and Juan de la Cierva (1895-1936), dealt with the insubordination of the junteros in a context of heightened popular unrest in the whole country and autonomist agitation in Catalonia. Republican and Socialist political groups attempted to attract the insubordinate officers to their political positions, but the junteros did not transform into a subversive revolutionary movement. It was instead the Conservative politician Antonio Maura (1853-1925) who the junteros trusted the most as an eventual Prime Minister. The basic corporate goals of the movement prevailed over political aims. Furthermore, the army was used to counter the workers’ strikes that broke out in August 1917.

The pressure of the Juntas heightened during the autumn of 1917, a critical period for many European countries that were fighting the First World War. In November 1917, Alfonso XIII, King of Spain (1886-1941) established a new government under Manuel García Prieto, concentrating representatives of different political forces. A Conservative civilian, Juan de la Cierva, was appointed Minister of War. La Cierva was sympathetic to the army and worked to make some concessions to the Juntas, while simultaneously manoeuvring to put them under his control. He tried to manipulate the independent Juntas of reserve officers as a way to break the unity of the movement. The War Ministry managed to exert some influence over Juntas, but the junteros gained too much leverage over civilian politics, thus debilitating the Spanish parliamentary system.

Another of La Cierva’s strategies to cope with military discontent was to pass, by decree, a military reform bill in 1918. Projects for military reform drafted by earlier governments had been discarded. In an earlier Romanones’ government, War Ministry General Augustín Luque (1850-1935) had tried to reform the army by increasing the troops to 180,000 while substantially reducing the number of officers. This project also planned to establish a more selective system of promotions. La Correspondencia Militar opposed these changes. Despite the compromises that Luque was ready to make, the Juntas de Defensa strongly reacted against the implementation of the Bill. When La Cierva, a minister more open to yielding to the Juntas’ demands, took office, he drafted a new military reform bill.[9] He manoeuvred to get the bill approved before it could be rejected or corrected by the Spanish parliament. In reality, La Cierva’s decreed reform did not resolve any of the many structural problems of the Spanish army. In fact, his reform aggravated the situation. His bill was written to satisfy the desires of the Juntas. The bill unnecessarily expanded the number of divisions from fourteen to sixteen, raising troop numbers to 180,000 but perpetuating the excess of officers. Responding to the war-related increase in the cost of living, officers’ salaries were augmented, but the higher ranks were better rewarded. These stipulations only made the prospects of promotion to higher ranks more interesting for the lower scales, and thus the number of officers would further swell in the near future. Moreover, La Cierva’s Bill established that all promotions in times of war and peace would be made on the basis of seniority, not war merits. This was a clear concession to the Juntas, but detrimental to the Africanistas. In other words, this measure punished those officers who sought more active professional duties, and benefited lazier army bureaucrats – a blow to the morale of the army in the Protectorate. Further sections of the Bill talked about modernization and expansion of equipment, including an Aeronautics service. These promises were dead letters because the available budget would be soon exhausted to pay the officers’ salaries. In short, the principal objective of La Cierva’s bill was appeasing the discontented military. The Juntas, however, did not disappear, and continued being a political problem in years to come.

Defence and Security↑

The Mediterranean and the Atlantic↑

Taking into account the country’s military and strategic situation it is not surprising that Spain remained neutral during the First World War.[10] Most importantly, naval resources were totally inadequate for the defence of the almost 8,000 kilometres of Spanish coast, including islands in the Mediterranean and Atlantic. There were only three relevant naval bases: Cartagena in the Mediterranean; Cádiz on the southern Atlantic coast; and El Ferrol on the northern Atlantic coast. The Balearic Islands in the Mediterranean with their main port of Mahon were particularly susceptible to the interference of the French navy. The Canary Islands in the Atlantic were likely to come under the domination of the powerful British navy. A few months after the First World War broke out, the government rushed to draw a new naval rearmament programme, but this project was focused on building a defensive fleet. There was no powerful coast artillery.[11] Within the country, there was not enough infrastructure to allow for a rapid transportation of troops from one region to another. It is significant that Spanish troops used to be transported to the Moroccan Protectorate by steamers of the Transatlántica Company, rather than warships.

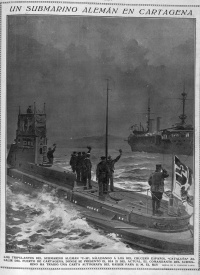

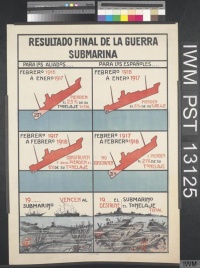

The possibility of using Spanish ports was a coveted asset for both sides fighting the First World War. If Spain remained benevolent, the British possession of Gibraltar provided the Entente with an important strategic position in the region.[12] Allowing the British to ensure communication between the Atlantic and the Mediterranean, Gibraltar served during the war as a logistic and commercial centre. Spanish authorities barely had the resources to monitor illegal foreign activities in Spanish ports and territorial waters.[13] For instance, in 1915 the German supply vessel Macedonia, which had been interned in Las Palmas (in the Canary Islands) since the beginning of the war, managed to elude vigilance and escaped towards South America to provide German battleships with provisions.[14] The Mediterranean came under the domination of the Allies after Italy’s entry in the war in May 1915, but German submarines constituted an important threat. During the war, there were different incidents related to the presence of foreign ships in the Spanish territorial waters. These conflicts endangered Spanish neutrality. In March 1916, Germany declared war on Portugal after a number of German and Austro-Hungarian ships had been interned in Lisbon following a British request.

In February 1917, when Germany declared the beginning of unrestrained submarine warfare, neutrality again came under threat. Waters surrounding the Iberian Peninsula became a zone of submarine warfare.[15] In April 1917, a German submarine torpedoed the San Fulgencio, a Spanish ship that was transporting coal from Britain to Barcelona. This attack led to a clearer Spanish inclination for the Allies. However, Spain was not yet able to react assertively. Shortly after the sinking of the San Fulgencio, pro-Entente Prime Minister Romanones, who had sent a very tough diplomatic note of protest to the Germans, was forced to resign. Spanish pro-German sectors, including many military officers, were still influential. In general, Spain was subject to the diplomatic pressure of both the Entente and the Germans. The Entente powers were interested in having Spain as an economic and commercial partner rather than a weak belligerent ally. Furthermore, the Germans preferred to maintain Spain’s strict neutrality. Joining the war in favour of the Central Empires side would have probably meant immediate invasion of Spain, the loss of Morocco, the Balearic Islands and the Canary Islands. The Spanish army and the navy were not prepared to face such a situation; nor would the Germans have been in a position to defend Spain. Maintaining neutrality was the only possibility to preserve Spanish interests.

North Africa↑

The intense political struggles that took place in Spain during the war, and particularly in 1917, contrasted with the general tranquillity of the situation in the Moroccan Protectorate, the main military setting for the Spanish army. In Morocco, High Commissioner General Marina Vega preferred to negotiate with the native rebels rather than seek a military solution. Other generals, such as Manuel Fernández Silvestre (1871-1921), demurred, but in the context of the First World War it was preferable to maintain peace in the region. The French authorities requested Spain to stop all military actions in the Protectorate when the European war broke out. In May 1915, two Spanish junior officers who were opposed to the strategy of negotiation were found responsible for the murder of one of El Raisuli’s agents in Tangier. After this incident, both Marina Vega and Silvestre were recalled. When General Francisco Gómez Jordana (1876-1944), the military governor of Melilla, was appointed High Commissioner on July of 1915, he was instructed to continue negotiating with the rebels, and reached a compromise with El Raisuli. Thus, Spanish military operations in Morocco came to a halt: but this came at the price of letting the Berber leader exert his independent authority in the north-western corner of the Protectorate. In 1914, troops in each of the Spanish garrisons of Melilla and Ceuta numbered approximately in 20,000, and in 1915 there were 14,000 military personnel in Tetuán. An additional garrison was established in Larache. A total of 75,000 troops (60 percent of the entire Spanish army) were deployed in Morocco at the beginning of the war.[16] Yet Spanish control over Morocco was so ineffective that, in May 1917, General Miguel Primo de Rivera (1870-1930), military commander at Cádiz and future Spanish dictator, publicly suggested that most of the Protectorate should be transferred to Britain in exchange for Gibraltar. Military activity in Morocco decreased further in early 1917, when Germany resumed unrestrained submarine warfare.[17]

During the years of the First World War, the grave social and political confrontations in Spain were not echoed in the Spanish zone of influence in Morocco with the same intensity. Spanish authorities and the Entente strived to maintain this quiet situation in Morocco, since the region was much more likely to endanger the official neutrality of Spain than what happened within the country. Other factors contributed to tranquillity in Morocco. Divisions between pro-Entente and pro-German groups were less acute in the Protectorate, where the officers’ opinion was overwhelmingly favourable to the Germans. The increasing rivalry between Africanistas and junteros(as the peninsula-based officers came to be known) had less dramatic consequences in the Spanish zone of influence in Morocco, where the Juntas were also present. The Africanistas were not a majority among the soldiers serving in Morocco; they were rather an elite of officers from the recently created Regulares and Policía Indígena units.

German agents who sought to provoke native unrest in the region constituted the main interference brought to the Spanish zone of influence in Morocco by the First World War.[18] Allied with the Ottoman Empire, the Germans aimed to arouse the reaction of Islam against the colonial domination of Britain and France. This strategy collided with important obstacles in Morocco. The Moroccan sultan was traditionally independent from the Turks. However, the Germans succeeded in establishing a connection with leaders of the Rif such as Abd-el-Krim (1882-1963), who received German money and weapons to use against the French colonial troops. Spanish military authorities were conscious of these covert German activities. Not only the pro-German leanings of military officers in Morocco, but also the poor equipment and organization of the Spanish troops, contributed to the tacit tolerance of German operations in the Spanish Protectorate. French military authorities, in particular Marshal Hubert Lyautey (1854-1934), Resident-General of French Morocco, recriminated Spanish leniency towards the German activities. Yet the Spanish government could only admit its impotence regarding its zone of influence. Indeed, the rebellious attitude of Moroccan tribes constituted an important problem for the French in their own Protectorate. This situation caused tensions between the French and Spanish authorities, extending the image of Spain as an unreliable colonial partner.

Conclusion↑

The Spanish army during the First World War remained militarily inactive and politically restless. The sheer inefficacy of the armed forces, as demonstrated in the Spanish zone of influence in Morocco, was one of the key reasons to maintain Spanish neutrality in the conflict. The strategic vulnerability of Spain and its dependence on the European powers were further motives to keep walking the tightrope of neutrality in spite of events that might have pushed the country to intervene. Deep internal divisions within Spanish society, and even within the army, completed the picture. Far from being galvanized by the First World War experience, the Spanish army fell deeper into the structural problems and vices that had been brewing since 1898 and would cast a very long shadow over its future.

Ángel Alcalde, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München

Section Editor: Carolina García Sanz

Notes

- ↑ Bönker, Dirk: Militarism in a Global Age. Naval Ambitions in Germany and the United States before World War I, Ithaca 2012.

- ↑ Rubio Márquez, David: Regeneracionismo en la Armada: La política naval española y los proyectos de creación de una nueva escuadra (1899-1909), Doctoral dissertation, UNED 2014.

- ↑ Morales Lezcano, Víctor: El colonialismo hispanofrancés en Marruecos (1898-1927), Madrid 1976.

- ↑ Romanones, Conde de: Reformas Militares, Madrid 1915, pp. 25-33.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 33.

- ↑ Payne, Stanley G.: Politics and the Military in Modern Spain, Stanford 1967.

- ↑ Payne, Politics 1967, p. 120.

- ↑ Romero Salvadó, Francisco J.: Spain’s Revolutionary Crisis of 1917: A Reckless Gamble, in: Romero Salvadó, Francisco J. / Smith, Angel (eds.): The Agony of Spanish Liberalism. From Revolution to Dictatorship 1913–23, Basingstoke 2010, pp. 62-91.

- ↑ Boyd, Caroline P.: Praetorian Politics in Liberal Spain, Chapel Hill 1979, pp. 94-115.

- ↑ Ponce, Javier: World War I: Unarmed Neutrality, in: Bowen, Wayne H. / Álvarez, José E. (eds.): A Military History of Modern Spain. From the Napoleonic Era to the International War on Terror, Westport 2007, pp. 53-67.

- ↑ Romanones, Conde de: El Ejército y la política. Apuntes sobre la organización militar y el presupuesto de la guerra, Madrid 1920, pp. 207, 215-217.

- ↑ García Sanz, Carolina: Gibraltar, 1914-1918: Guerra y comercio aliado en el Mediterráneo, in: Historia Contemporánea 41 (2010), pp. 291-319.

- ↑ Ponce, World War I 2007, pp. 65-66.

- ↑ ABC (Madrid), 1 April 1915.

- ↑ Perea Ruiz, Jesús: Guerra submarina en España, in: Espacio, Tiempo y Forma. Serie V. H.ª Contemporánea 16 (2004), pp. 193-229.

- ↑ La Porte, Pablo: La espiral irresistible. La Gran Guerra y el Protectorado español en Marruecos, in: Hispania Nova. Revista de Historia Contemporánea 15 (2017), pp. 500-526.

- ↑ Payne, Politics 1967, p. 122.

- ↑ La Porte, La espiral 2017, pp. 515-516.

Selected Bibliography

- Boyd, Carolyn P.: Praetorian politics in liberal Spain, Chapel Hill 1979: University of North Carolina.

- García Sanz, Carolina: Gibraltar, 1914-1918. Guerra y comercio aliado en el Mediterráneo, in: Historia Contemporánea 41, 2010, pp. 291-319.

- La Porte, Pablo: La espiral irresistible. La Gran Guerra y el Protectorado español en Marruecos, in: Hispania Nova 15, 2017, pp. 500-526, doi:10.20318/hn.2017.3499.

- Payne, Stanley G.: Politics and the military in modern Spain, Stanford 1967: Stanford University Press.

- Perea Ruiz, Jesús: Guerra submarina en España (1914-1918), in: Espacio Tiempo y Forma. Serie V, Historia Contemporánea 16, 2004, pp. 193-229.

- Ponce, Javier: World War I. Unarmed neutrality, in: Bowen, Wayne H. / Alvarez, José E. (eds.): A military history of modern Spain. From the Napoleonic era to the international war on terror, Westport 2007: Praeger Security International, pp. 53-67.

- Romero Salvadó, Francisco J.: Spain’s revolutionary crisis of 1917. A reckless gamble, in: Romero Salvadó, Francisco J. / Smith, Angel (eds.): The agony of Spanish liberalism. From revolution to dictatorship, 1913-23, Houndmills; New York 2010: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 62-91.