Creation↑

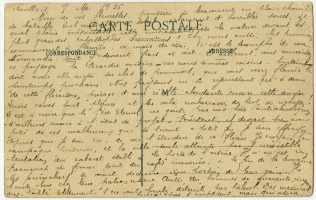

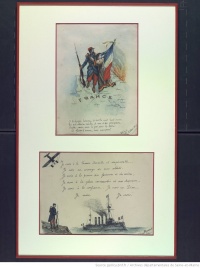

Alternately celebrated and criticized, the figure of the female wartime pen pal exemplifies the classic duality found in thinking about women during the First World War. Marguerite De Lens created the La Famille du Soldat charity in January 1915 to provide moral support to soldiers from invaded regions in the north and east of France who were unable to receive mail from their families. The idea was simple: as hopes of a short war faded and given the importance of the moral support provided by letters and parcels, the goal was to forge ties through letter-writing between isolated soldiers and people on the home front. The charity fell under the patronage of Jules Cambon (1845-1935), Secretary General of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and received the blessing of the academic and nationalist politician Maurice Barrès (1862-1923), who wrote about it in April 1915 in the Echo de Paris newspaper. It quickly became an unmitigated success. Its popularity reflected an overall increase in letter-writing among people from all social backgrounds, which occurred from the start of the war. Henriette de Vismes (1884-?), the author of the only book on the history of these wartime pen pals, published in 1918, estimated that 25,000 soldiers were involved in the Famille du Soldat initiative, primarily paired with French pen pals, but also with American, Dutch, Norwegian and Swiss women. Other similar associations were also created: Mon Soldat, founded in 1915 with support from the War Minister, Alexandre Millerand (1859-1943), the Marraines de la Croix Verte and the Marraines de la Fraternelle des Combattants Roubaisiens organization. Newspapers such as the Echo de Paris, L’Homme enchaîné and La Croix acted as intermediaries and put their readers in touch with soldiers who had expressed interest.

Isolated Soldiers↑

The initiative was first aimed only at isolated soldiers, who were put into contact with all willing letter-writers behind the lines – both men and women –, but it was soon expanded, on the one hand, to include any soldier who wished to participate and limited, on the other hand, to female pen pals. The chosen name – “Marraines”, which also means “godmother” in French – emphasized the religious angle. Female pen pals were meant to fill in for the soldiers’ families, as well as provide moral support through their letters and even potentially material support via parcels. However, in a war that massively mobilized men and made it difficult for men and women to meet, letter-writing between strangers of the opposite sex was quickly suspected of serving other purposes. The French army was further concerned about the risk of espionage and argued that correspondents claiming to be pen pals might use the information naively provided by soldiers in their letters for ulterior motives. In this respect, it is interesting to note that Britain forbade the creation of such a system within its army.

Success and Interpretation↑

Proof of the popular success of the institution and its contradictory interpretations can be found in novels, plays and songs that either glorify the female pen pals and soldiers to whom they wrote, emphasizing the patriotic aspect and the goodness of the women involved, or mock letter-writing practices ultimately aimed at flirting and deceit, far from the innocence imagined by the scheme’s creators. Female letter-writers and their male pen pals have become literary figures portrayed either as emblematic of the Union sacrée or as representative of the immorality and degeneration of the nation. And yet, despite all the suspicion, the institution of wartime pen pals created during the Great War was revived in 1939.

Clémentine Vidal-Naquet, Paris-Sorbonne

Section Editor: Emmanuelle Cronier

Translator: Jocelyne Serveau

Selected Bibliography

- Grayzel, Susan R.: Mothers, marraines, and prostitutes. Morale and morality in First World War France, in: The International History Review 19/1, 1997, pp. 66-82.

- Le Naour, Jean-Yves: Epouses, marraines et prostituées. Le repos du guerrier, entre service social et condamnation morale, in: Morin-Rotureau, Evelyne (ed.): Combats de femmes, 1914-1918. Les Françaises, pilier de l'effort de guerre, Paris 2014: Autrement, pp. 63-79.

- Le Naour, Jean-Yves: Les marraines de guerre. L’autre famille des soldats, in: Les Chemins de la Mémoire 181, 2008, pp. 7-10.

- Vismes, Henriette de: Histoire authentique et touchante des marraines et des filleuls de guerre, Paris 1918: Perrin.