Internment Measures↑

In all belligerent states during the First World War, the internment of civilians from "hostile" foreign countries was standard practice. In Austria-Hungary, too, the state authorities were confronted with the problem of the treatment of thousands of now “enemy aliens” who were living and working in Austria at the outbreak of war.

The Austro-Hungarian government decided, as a safety measure, to forbid them from leaving the country. It was checked whether they were fit for military service, and, if so, they were interned in special locations - in “depots” and later in small camps. Most of these locations were established at the beginning of the war in Lower Austria.

The reasons why they were taken there were the geographic location far away from the war zone and the lack of armament factories and military objects. Therefore, espionage was reduced to a minimum. Last but not least, the German-speaking population there was loyal to the authorities, by which an additional controlling function was created.

The enemy aliens were divided into two classes:

a) Interned: they were (mostly) destitute, were fed at the state’s expense and were under military guard

and

b) Confined (Konfinierte): they lived in private houses (pensions, rural hotels), enjoyed more freedom, were obliged to regularly report every day to the local police authorities and fed themselves from own financial means. So-called “Konfinierungsstationen” were established for them in small towns far away from the big cities and important railway lines. Here, between fifty and 150 persons could be housed, depending on the size of the site and the existing housing options. The management lay in the hands of the confined under control of the mayor of the town or the local doctor.

A “Little Town” for Jewish Internees↑

The biggest camp in the Waidhofen an der Thaya district was in Markl (Windigsteig). Established in Markl in 1915/1916 on the initiative of the head of the district government, it was located in a vacant Meierhof (square courtyard) owned by the Baroness Widmann from Schwarzenau and its surrounding area, comprising 50,000 square-meters, with a capacity of up to 1,400 people.

The reason for imprisoning them here was that the Jewish internees - many were born in Russian Poland and Russia - from the Drosendorf and Illmau camps wanted to live according to Orthodox rites, especially that of eating kosher. With the support of the Jewish communities in Vienna and Waidhofen an der Thaya, a “small town” emerged, in which not only men, but also women and children – who joined their husbands and fathers voluntarily, because they were out of money – were interned in lodgings especially established for them. In addition to a synagogue, a separate school was erected for the numerous children, who were taught by local and interned teachers.

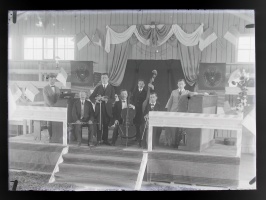

The camp consisted of the Meierhof, where the camp’s management and the military command were situated, and several wooden barracks for the other camp facilities.

Administration and Life in the Camp↑

For the control of the camp, special management was arranged, which was supported in fulfilling its duties by a commanding officer and a director who was determined by the district government. Both of them were members of the Jewish community of Waidhofen an der Thaya. The camp management had to maintain an exact personnel register with all necessary data (age, religion, employment, state, etc.) of the internees, to supervise the censorship of letters, to maintain the order of the house and the cleaning of the linen, clothes and rooms, and to provide supplies. In addition to the provision of food and clothing to the prisoners, it was responsible for the preservation of the camp objects and arrangements. Furthermore, it also controlled the state funds, the monetary depots of the internees as well as the workshops and stores.

All the money which was necessary for the camp’s construction, for keeping it in good condition, and for supplying food and clothes was provided by the ministry of the interior (refunded during the war by the k.u.k. Kriegsministerium (Ministry of War), because the internment measures were part of the military emergency measures). The district administration in Waidhofen an der Thaya was responsible for proper use of the funds.

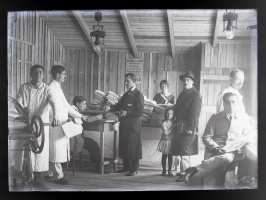

In its role, the camp management was also supported by well-chosen internees, in particular in the safekeeping of and account processing and accounting for the cash from the prisoners, and also in all matters concerning the feeding and clothing of the prisoners. The costs for heating, lighting, the facilities of the living rooms, the eating dishes and cooking dishes, the house devices and all other tools were borne by the state and all repair works in the camp were effected by interned workers and craftsmen for low wages. The camp’s surveillance was militarily organised. Regular “Landsturm” units as well as members of the “Schützenkorps” of Waidhofen an der Thaya, Eggenburg and Raabs an der Thaya fulfilled this duty. The food costs for destitute internees were borne by the state. A canteen, which was operated by the prisoners themselves, was also established in the camp. The goods available here had to be paid for by the internees, unless they still had enough money in their depot.

From the first day after the establishment of the camp in Markl, the able-bodied internees were utilized for a variety of work (adaptation of the rooms, construction of all wooden buildings in the following years, etc.). All their work in the camp was well remunerated according to the nature of their activities. Due to the increasing labor shortage, more and more internees were assigned to work outside the camp. Mainly, these workers were forced to work in the agricultural sector or in commercial and industrial enterprises in the districts of Waidhofen an der Thaya and Horn as well as Vienna.

For the medical treatment of the internees, a hospital barrack with thirty beds was available. The health care was based on a special “Sanitätsordnung”, which was drafted by the regional administration bodies. The care of the sick people in the camp hospital was done by interned doctors and medical students.

The reaction of the local population to the internees was divided. Traders, innkeepers, and farmers in the area who were in an economic relationship with the Markl camp normally could not complain – they had a secure income during the war. On the other hand, after the establishment of the camp in summer 1915, it came, anonymously, to the worst anti-Semitic allegations towards and defamation of the Jewish director of the camp, who was a member of the Jewish community of Waidhofen an der Thaya. Therefore, anti-Semitic remarks in the local population increased the longer the war lasted.

At the beginning of 1918, the repatriation of the interned Jews from occupied (by the Central Powers) Poland began. After the peace treaties with the Ukrainian People's Republic (9 February 1918) and with Russia (3 March 1918 in Brest-Litovsk) the Jews from these countries followed. These repatriations were carried out as quickly as possible, because the supply situation in the camp was getting worse and the internees urged to return home as soon as possible. In the middle of August 1918, the camp was completely evacuated.

Reinhard Mundschütz, Medizinische Universität Wien

Section Editor: Tamara Scheer

Selected Bibliography

- Mundschütz, Reinhard: Internierung im Waldviertel. Die Internierungslager und -stationen der Bezirkshauptmannschaft Waidhofen an der Thaya 1914-1918, thesis, Vienna 2002.

- Mundschütz, Reinhard: Das Internierungslager Drosendorf-Thaya 1914-1920. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Behandlung 'fremder' Staatsangehöriger in Österreich während des 1. Weltkrieges, thesis, Vienna 1993.

- Mundschütz, Reinhard: Das Internierungslager in Großau während des Ersten Weltkrieges 1914-1918, in: Nagl, Ignaz (ed.): Geschichte und Geschichten aus Großau und Umgebung. Mit Anhang, Raabs an der Thaya 2008: I. Nagl, pp. 58-76.

- Stibbe, Matthew: 'Ohne jede Ausnahme eine Schar von Feinden Österreichs'. Die Internierungspolitik des Habsburgerreiches im europäischen und globalen Kontext, in: Fritz, Peter (ed.): Jubel & Elend. Leben mit dem Grossen Krieg 1914-1918, Schallaburg 2014: Schallaburg Kulturbetriebsges. m.b.H., pp. 338-343.

- Strasser, Josef: Feindliche Ausländer im Waldviertel, 1 September 1916.

- Zak, Alphons: Die Stationen der Internierten, Konfinierten und Flüchtlinge im niederösterreichischen Waldviertel (1914-1918), 1929, p. 56-62.