Communities of Loyalty↑

New Zealanders’ communities of loyalty entailed racial, political, historical, economic, sentimental, and pragmatic bonds. They provided a firm, stable, and confident sense of belonging that bolstered and explained duty, and provided the benchmark for commitment and loyalty – and highlighted any deviation from it. There were, however, limits to loyalty and feelings of duty, especially as the conflict dragged on, as the needs and loyalty of some communities seemed to be sacrificed in the name of others.

Three interlocking and mutually supporting communities were at the heart of New Zealanders’ experiences of the Great War: Empire, district, and family. Membership in the British Empire was central to many Pākehā (non-Māori New Zealanders) and Māori understandings of the Great War, and was expressed in a variety of ways. On the other hand, iwi and hapu (tribal) affiliations and the nature of interactions with the Crown since 1840 shaped Māori conceptions of loyalty and commitment to the war.

Districts provided geographical cohesion for identities and communities that were closer to hand and experienced in the everyday by non-combatants, such as streets, schools, and churches. Finally, family provided the most intimate setting in which the war was understood by Pākehā New Zealanders. It was in this setting that loyalty to the Empire could be over-ridden by anxiety, love, loss, and bitterness – and self-interest. The war was a much more complex event at a family level than it appeared at the larger scales of analysis of district and Empire.

Empire↑

Membership in and loyalty to the British Empire was the racial, cultural, and sentimental umbrella under which participation, meaning, and everyday life sheltered. This was underscored by New Zealand’s status as a self-governing Dominion, granted in 1907, a privilege also granted to the other “British” white settler colonies. In the late 19th century, scholars of Empire argue, the notion of a British “race” was a key, albeit contradictory determinant of imperial and national belonging. Daniel Gorman, for example, describes the pre-WWI notion of the British race as “a close synonym for ‘culture’, denoting the values and pedigree of a national people, including themselves.”[1] Stuart Ward argues that “Anglo-Saxon racialism” was far more pronounced in Australia and New Zealand than in either Britain or Canada, because of “the perceived sense of strategic vulnerability that came with being one of the most far-flung of Britain’s imperial outposts.”[2] Defence and imperial identity, then, were interdependent.

In 1914, more than half of Pākehā New Zealanders were British immigrants, and 30 percent of men enlisted in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) had been born in the UK.[3] The transnational entity of Empire was translated into comprehensible forms, from newspapers and schooling materials through to high and vernacular culture.[4] Visits in 1910 from Lord Horatio Herbert Kitchener (1850-1916), to review defence arrangements, and in 1912 from Lord Baden Powell (1857-1941) were hugely popular and reinforced New Zealand’s membership in the imperial family.

Such was the strength of imperial bonds that, while certainly causing anxiety as well as excitement, there was little questioning of the proclamation of war in August 1914.[5] (This enthusiasm had been foreshadowed the previous year, when hundreds of thousands of New Zealanders had stormed HMS New Zealand, a Royal Navy battlecruiser paid for by the Dominion.) So effectively had duty been inculcated in the male population, especially through compulsory military training from 1909, that recruiting offices were swamped and the government had to recall equipment and clothing from the Dominion’s territorial forces in order to arm the new expeditionary force.

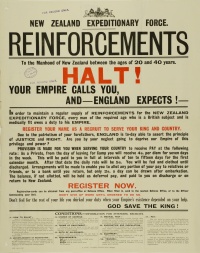

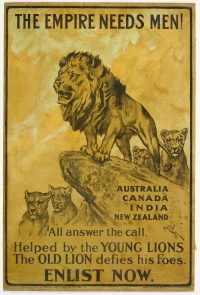

Recruiting materials came almost exclusively from the British government, but were hardly needed for the first months of the war. Posters emphasised the imperial nature of the war effort, as did newspapers with reports from all sectors of the conflict.[6] Families, too, saw themselves as engaged in a war that spanned the Empire. Ida Willis and her four brothers all served during WWI. Three of her brothers had emigrated to Canada and so served with the Canadian Expeditionary Force, one served with the NZEF, and Ida herself served with the New Zealand Army Nursing Service (NZANS).[7]

Schooling, Children, and Empire↑

Schooling was a prominent vehicle of Empire in everyday life in New Zealand and a key institution through which families and neighbourhoods made meaning during the war. As “little Britons” and future citizens, children were already prime targets for imperial ideology, and the war intensified official efforts through the national education curriculum. Ideas of duty and models of loyal behaviour were transmitted through readers, lessons, and repeated ritual practices such as flag-waving at farewells and events, and flag-raising ceremonies at schools during the conflict. The Royal Navy ensign was presented to and hoisted at Stoke School in Nelson after pupils won a fund-raising competition, with the officiating dignitary noting that “the flag stands for the strength of the Empire.”[8]

Schools also used the war as an opportunity to improve pupils’ knowledge of geography through war maps, with military and political leaders of each country often illustrated on prize certificates. Along with strengthening students’ knowledge of Europe, other regions became better known: Wellington Girls’ College boasted that “most girls can draw the Dardanelles with their eyes shut.”[9] The culture of “old boys” at boys’ schools modelled loyal imperial behaviour, especially at assemblies. Ex-pupil of Wellington College Wilfred Fitchett reminded the boys present “that some of them might before long be in the firing line.”[10] In public forums such as children’s pages of newspapers, which constituted reading communities not bound by geography, loyalty was expressed by young New Zealanders in a range of ways. “Gwen,” for example, wrote that the idea that fighting the Germans, and dying in the process, was “fulfilling the sacred heritage of our ancestors – for fighting for the highest ideals and protecting the weak.”[11]

District↑

If Empire was an overarching community of duty and loyalty, New Zealanders’ geographic communities shaped their everyday understandings of the Great War. New Zealand’s population in 1913 was just over one million, of which around half lived in towns and cities. Auckland, whose population including suburbs was 109,982, was the Dominion’s largest urban centre.[12] The combined population of the three other main cities centres was 224,450, and there were a further six towns with populations ranging between 11,000 and 18,000. But most New Zealanders (58 percent) lived in much smaller towns and villages. Districts were areas of local government, often with towns at their centre, but even in the most remote areas they were organised around community halls, churches, and schools. The geographical community of a district was actualised through daily travel and interaction, bureaucracy, and associational life, even while those living there were connected to nation-and empire-wide entities through trade unions, weekly newspapers and other communities of reading, and a national curriculum in schools.[13]

Initially, NZEF units were organised according to regional military districts. Such districts were very active in their farewells of enlisted men, and in outfitting and fundraising for soldiers and the wounded, as well as other war-related causes. In the North Island, for example, the Gisborne Women’s Patriotic Committee made 226 portable sewing kits (hussifs) for men leaving the district during the first four months of the war.[14] When Len Hart left his home, the South Island town of Lumsden, in February 1915, the railway station was packed with the townspeople. These well-wishers presented Hart with a “very handy” leather holdall filled with cutlery, a toothbrush, and needles.[15] These farewells were occasions when broader loyalties and allegiances to the Empire were also manifested through flags, speeches, and music.

At the end of the war, districts clamoured for trophies and lobbied the government for their fair share of them, highlighting local efforts in their arguments for acknowledgement. Some local districts rallied against a proposal for a national war museum to house and display the trophies sited in Wellington. Detractors argued that the war effort had been a local one, and the consequences were also felt locally. MP James Horn, for example, wrote in 1921 that his electorate deserved its own trophy because its inhabitants “did their best for the men …. in the way of send offs, relatives’ parcels, when at the Front and caring for and looking after dependants.”[16] Or as one newspaper put it:

In the face of large-scale death, too, the district remained a comprehensible organising principle. Sixteen-year-old “English Lassie” noted in June 1918 that “since [last] writing to the page another of our district’s young soldiers has made the supreme sacrifice. He was a very nice young fellow.”[18] In the very south of the South Island, the newspaper editor wrote “Biographicals” of soldiers killed during the conflict, listing their parents, schools attended, sporting teams or bands with whom they had played. Other newspapers solicited photographs of men killed, either publishing them as visual casualty lists, or, in the case of the small North Island town of Stratford, framing them to hang in a war memorial arcade.[19]

District war memorials were commonly erected after the war, especially in rural areas, during the first half of the 1920s, usually on the highest hill in the area. And, from 1916, as sacrifice was ritualised annually on 25 April in the form of Anzac Day, districts became public communities of mourners, to commemorate the loyalty of the men who had “lost” their lives in the conflict, and whose bodies would not be repatriated to be buried in local cemeteries. Memorial trees for individual soldiers were planted in the South Island district of North Otago, along the roads that the families of these local men lived, again so that they would be encountered incidentally yet every day. On the other hand, the national war memorial complex in Wellington took from 1932-1964 to complete.[20]

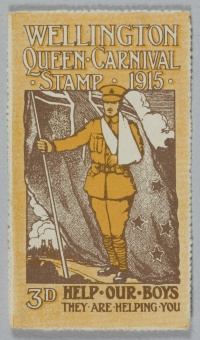

Districts were also a key site of leisure, most of which became increasingly oriented towards the conflict. Sports days, dances, and bazaars all became associated with fund-raising and patriotic activity, even while they continued their pre-war function of reinforcing the mutual social bonds of communities. In 1915, for example, many communities crowned local “Carnival Queens,” who were selected on the basis of their superior fundraising efforts. Their “coronations” were so popular that in the case of one, held in the farming centre of Marton in September 1915, the local train was delayed on two evenings so that locals could enjoy the coronation entertainments to the full.

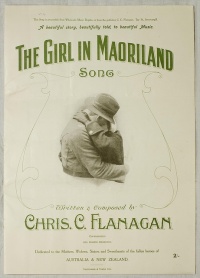

Cinema was another vehicle for war narratives. Movie-going became a primary leisure activity during the war, in large part because of its novelty and its coincidence with the war and people’s thirst for both news and escape. “Every town and hamlet” had its own cinema or visiting picture show.[21] In 1917, when an “amusement tax” was imposed on movie-going (and the population of New Zealand was just over one million), 500,000 tickets were sold in that year alone and cinema attendance outstripped church-going.[22] Newsreels with war news were staple fare, but in the 1920s, these were supplanted by war dramas and romances, significant genres produced by British studios and shown all over New Zealand. Marie Prevost, for example, starred in Recompense (1926) in the role of Julie Gamelyn, who had served as a nurse in France “so as to be near the man she loved.”[23]

However, districts could also be places of informal surveillance, of the behaviour of young men especially, and tension between neighbours. In reporting the news of the community to her children, Elinor Hunter-Brown noted (and subtly judged) the activities and good intentions of men they knew: “Siggleton is at Trentham [Military Training Camp], Adamson is having all his teeth out and as soon as he feels fixed up he will go. Mickey Walsh is always going.”[24] More seriously, in the lead-up to the passage of the Military Service Bill 1916, neighbours were encouraged to report young men not yet enlisted to the authorities under what became known as the “family shirkers’ clause.”[25] After the law came into effect, in November 1916, appeals against conscription were heard in public places, which presented opportunities for locals to monitor levels of loyalty, or its deficit.

Family↑

The family was the most immediate and intimate context in which official expressions of loyalty were worked through, negotiated, and performed. While most members of the NZEF were unmarried, these men had familial ties and roles as sons, brothers, nephews, and uncles. And, while not kin or connected by blood ties, the men also had emotional ties with sweethearts and fiancées.

Demonstrating family loyalty through a son’s military service was important, but fraught. Twenty-year-old Len Hart had enlisted without his parents’ knowledge, only writing to them when he had attested. His father had been taken aback at first, but wrote to Len that he felt “proud of being your father. Good men like you are going to save the Empire.”[26]

Families had to balance their competing needs and desires, however, often making decisions as a family about who would serve. Leslie Adkin’s family decided that Leslie should stay behind while his younger brother enlisted, because Leslie was a more experienced farmer and would be able to keep the family business going more effectively.[27] As this example indicates, duty came in several guises. When the New Zealand government conducted its war census in 1915, discovering that almost 190,000 eligible men had not yet volunteered for service, it was chiefly family responsibilities that held men back.[28] After the introduction of conscription in 1916, family duties were a significant platform of appeal for those balloted.[29]

Nonetheless, the notion of the “patriotic family” was rhetorically powerful in New Zealand. The Dominion Museum’s plans epitomised this idea. This was in keeping with the aims of the Imperial War Museum in London, which was established in 1916 as a place where the “individual [would] find the work of himself and his family exhibited for all time as a living acknowledgment of their sacrifices offered by them to the Empire.”[30]

From the outset, the museum focussed on individuals’ service through the medium of photography. The museum’s director, Allan Thomson (1881-1928), began collecting photographs of all New Zealand’s gallantry medal winners in 1916 – including those who served in other imperial forces. In 1917 and 1918, he also called for portraits of “patriotic families.” Writing to Military Medal winner Louis Wood in January 1918, Thomson stated his desire to “heartily congratulate you on the fine record of patriotism set up by your family. If you have a photograph of the four brothers who are maintaining the terrible struggle for freedom so manfully, I should like to have it included in the section of portraits devoted to ‘Patriotic Families’ of which we are collecting some very interesting examples”.[31]

That these personal photographs were being mobilized as a form of public remembrance connected family experiences of the war with those of the nation. Historian Sandy Callister suggests that the use in museum displays and on honour rolls of individuals’ images, usually solicited from families, was a way for the nation to “glorify and contain” the war.[32] Yet for families and kin, photographs were deeply emblematic of the intimate experiences of separation, anxiety, and sometimes loss. “In too many instances photographs were the last visible traces a soldier had of his family and his family of him.”[33]

Some families publicly mourned their dead through the pre-war practice of publishing death notices in the local newspapers. The Southland Times offered a heavily bordered column under the heading “For the Empire’s Cause,” in which families published a range of sentiments from Christian consolations to the causes of Empire, duty, and the protections of civilization and humanity. Other families deliberately eschewed this column, choosing to publish death notices in the other, non-military columns, claiming their sons back from the military in death.[34] In subsequent years, families who continued to place in memoriam notices in their local newspapers often shifted their expressions from those of sorrow, sacrifice and duty nobly done, to a focus on the lack of information around their sons’ deaths:

That is all the tale they tell

Of the brave young lads who loved us,

Of the lad we loved so well.

How the life was sped we know not;

What the last word, look or thought;

Only that he did his duty,

Died as bravely as he fought.[35]Conclusion↑

The celebrations attending the declaration of the Armistice in November 1918 in the rural Taranaki district reflected these connected communities of loyalty through which many New Zealanders had made sense of the conflict. The Union Jack was prominent; the “army and the workers of the British Empire” were praised for their role in defeating Germany; speeches praised children and women for their cheerfulness and steadfastness. Other commentators reminded crowds to be “careful how they rejoiced on these occasions. Lest they injured the feelings of those … who were beneath a dark cloud of sorrow…”[36] The influenza epidemic sweeping the country also prompted reflection on the costs of the war: Reverend Gavin wondered “if it really comes home to us all the price we have had to pay for the victory.”[37]

Districts welcomed home the soldiers whom they had farewelled and erected memorials to the men who did not return. Family played a critical role in re-orienting men back into everyday post-war life. In the immediate post-war years, New Zealand’s marriage rate leapt. In 1919, it grew to 150 percent of the 1918 rate, and in 1920, the rate was double that of 1918.[38]

Loyalty to the British Empire remained strong, however, and enormous cheering crowds greeted the then Prince of Wales, Edward, Duke of Windsor (1894-1972) on his 1920 tour of New Zealand. The Prince‘s right hand was shaken so vigorously by the veterans he met that he had to use his left. These communities of belonging were thus invoked and re-purposed to structure the demands of adjusting to the peace.

Kirstie Ross, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

Section Editor: Kate Hunter

Notes

- ↑ Gorman, Daniel: Imperial Citizenship. Empire and the Question of Belonging, Manchester 2006, p. 150, emphasis in original. See also the survey of the substantial literature on Dominionism and Empire in Schreuder, Deryck M. / Ward, Stuart: Introduction. What Became of Australia’s Empire?, in: Schreuder, Deryck M. / Ward, Stuart (eds.): Australia’s Empire, Oxford 2008.

- ↑ Ward, Stuart: Security. Defending Australia’s Empire, in: Schreuder / Ward 2008, p. 242.

- ↑ Hearn, Terry / Philips, Jock: Economic Growth and Renewed Immigration, 1891-1915, New Zealand Ministry of Culture and Heritage, 9 December 2014, available online: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/culture/home-away-from-home/sources; Hunter, K. M.: National and Imperial belonging in Wartime. The Tangled Knot of Australians and New Zealanders as British Subjects during the Great War, in: Australian Journal of Politics and History 63/1 (2017), p. 34.

- ↑ Malone, E. P.: The New Zealand School Journal and Imperial Ideology, in: New Zealand Journal of History 7/1 (1973), pp. 12-27; Ballantyne, Tony: Thinking Local. Knowledge, Sociability and Community in Gore’s Intellectual Life, 1875-1914, in: New Zealand Journal of History 44/2 (2010), pp. 138-156; Potter, Simon: News and the British World. The Emergence of an Imperial Press System, 1876-1922, Oxford 2003.

- ↑ Hucker, Graham: A Great Wave of Enthusiasm. New Zealand Reactions to the First World War in August 1914 – A Reassessment, in: New Zealand Journal of History 43/1 (2009), pp. 59-75.

- ↑ Gibson, Stephanie: First World War Posters at Te Papa, in: Tuhinga. Records of the Museum of New Zealand 23 (2012), pp. 69-84.

- ↑ Willis, Ida G.: A Nurse Remembers, Wellington c. 1965.

- ↑ Flag hoisting ceremony at Stoke School, in: Nelson Evening Mail, 12 August 1915, p. 6.

- ↑ Girls’ College Reported, 1915, cited in Bennett, Charlotte: Now the war is over, we have something else to worry us. New Zealand children’s responses to crises, 1914-18 (MA thesis), Victoria University of Wellington 2012, p. 22.

- ↑ Wellingtonian magazine, December 1915, cited in Bennett, Now the war is over 2012, p. 27.

- ↑ Gwen, in: Otago Witness, 26 June 1918, cited in Bennett, Charlotte: Now the war is over, we have something else to worry us. New Zealand children’s responses to crises, 1914-18, in: Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth 7/1 (2014), p. 28.

- ↑ New Zealand Yearbook, 1913, available online: https://www3.stats.govt.nz/New_Zealand_Official_Yearbooks/1913/NZOYB_1913.html

- ↑ See for example Liebich, Susann: Connected Readers. Reading Practices and Communities across the British Empire, 1890-1930 (PhD thesis), Victoria University of Wellington 2012. Ballantyne, Tony: Thinking Local. Knowledge, Sociability and Community in Gore’s Intellectual Life, 1875-1914, in: New Zealand Journal of History 44/2 (2010), pp. 138-156.

- ↑ Hunter, Kate / Ross, Kirstie: Holding on to Home. New Zealand Stories and Objects of the First World War, Wellington 2014, p. 23.

- ↑ Len Hart cited in Hunter / Ross, Holding on to Home 2014, p. 38.

- ↑ James Horn cited in Hunter / Ross, Holding on to Home 2014, p. 257.

- ↑ Mataura Ensign, 18 September 1918 cited in Ross, Kirstie: More than books tell. Museums, artefacts and the history of the Great War, in: Pickles, Katie et al. (eds.): History Making a Difference. New Approaches from Aotearoa, Newcastle upon Tyne 2017, p. 239.

- ↑ Cited in Bennett, Now the war is over 2012, p. 85.

- ↑ See Hunter, Kathryn: Sleep on dear Ernie, Your battles are o’er. A Glimpse of a Mourning Community. Invercargill, 1914-1925, in: War in History (2007), pp. 36-62; Hucker, Graham: A hall of remembrance and its narrative of the Great War, unpublished paper presented at Public History, Meanings, Ownership, Practice conference, Wellington, New Zealand, September 2000.

- ↑ Phillips, Jock: To the Memory. New Zealand’s War Memorials, Wellington 2016.

- ↑ Greenhalgh, Charlotte: Bush Cinderellas. Young New Zealanders and Romance at the Movies, 1919-1939, in: New Zealand Journal of History 44/1 (2010), p. 3.

- ↑ Greenhalgh, Bush Cinderellas 2010, p. 4. Bourke, Chris: Goodbye Maoriland. The Songs and Sounds of New Zealand’s Great War, Auckland 2017.

- ↑ Recompense described in New Zealand Theatre & Motion Picture magazine, 1 June 1926, p. 24.

- ↑ Baker, Paul: King and Country Call. New Zealanders, Conscription and the Great War, Auckland 1988, p. 48.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 108.

- ↑ Samuel Hart to Len Hart, 19 February 1915, MS-Papers-2157-1, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington.

- ↑ Hunter / Ross, Holding on to Home 2014, p. 26.

- ↑ Baker, King and Country Call 1988, p. 58.

- ↑ Littlewood, David: Willing and Eager to go in their Turn. Appeals for Exemption from Military Service in New Zealand and Great Britain, 1916-1918, in: War in History 21/3 (2014), pp. 338-354.

- ↑ The Imperial War Museum booklet, c. 1917, p. 9. WA10 3 ZWR 6/8 part 2, Archives New Zealand.

- ↑ Thomson to Louis Wood, 3 January 1918, AALZ 907, Archives New Zealand.

- ↑ Callister, Sandy: Faces of War, Auckland 2008, p. 75.

- ↑ Callister, Sandy: Picturing Loss. Family, Photographs and the Great War, in: The Round Table 96/393 (2007), p. 665.

- ↑ Hunter, Sleep on dear Ernie 2007, p. 53.

- ↑ Southland Times, 1 October 1917, p. 4.

- ↑ Cited in Hucker, Graham: The Armistice. Responses, Understandings and Meanings for a Rural Region, in: Crawford, John / McGibbon, Ian: (eds.), New Zealand’s Great War, Auckland, 2007, pp. 578-579.

- ↑ Cited in Hucker, The Armistice, p. 579.

- ↑ Hunter / Ross, Holding on to Home 2014, p. 266.

Selected Bibliography

- Baker, Paul: King and country call. New Zealanders, conscription, and the Great War, Auckland 1988: Auckland University Press.

- Ballantyne, Tony: Thinking local. Knowledge, sociability and community in Gore's intellectual life, 1875-1914, in: The New Zealand Journal of History 44/2, 2010, pp. 138-156.

- Bennett, Charlotte: 'Now the war is over, we have something else to worry us'. New Zealand children’s responses to crises, 1914-1918, in: The Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth 7/1, 2014, pp. 19-41.

- Bourke, Chris: Good-bye Maoriland. The songs and sounds of New Zealand's Great War, Auckland 2017: Auckland University Press.

- Callister, Sandy: Picturing loss. Family, photographs and the Great War, in: The Round Table 96/393, 2007, pp. 663-678.

- Gibson, Stephanie: First World War posters at Te Papa, in: Tuhinga 23, 2012, pp. 69-84.

- Gorman, Daniel: Imperial citizenship. Empire and the question of belonging, Manchester 2006: Manchester University Press.

- Hucker, Graham: The armistice. Responses, understandings and meanings for a rural region, in: Crawford, John / McGibbon, Ian C. (eds.): New Zealand's Great War. New Zealand, the Allies, and the First World War, Auckland 2007: Exisle Publishing, pp. 569-582.

- Hucker, Graham: 'The great wave of enthusiasm.' New Zealand reactions to the First World War in August 1914 - A reassessment, in: The New Zealand Journal of History 43/1, 2009, pp. 59-75.

- Hunter, Kate: National and imperial belonging in wartime. The tangled knot of Australians and New Zealanders as British subjects during the Great War, in: Australian Journal of Politics & History 63/1, 2017, pp. 31-44.

- Hunter, Kate: ‘Sleep on dear Ernie, your battles are o’er.’ A glimpse of a mourning community. Invercargill, New Zealand, 1914-1925, in: War in History 14/1, 2007, pp. 36-62.

- Hunter, Kate / Ross, Kirstie: Holding on to home. New Zealand stories and objects of the First World War, Wellington 2014: Te Papa Press.

- Liebich, Susann: Connected readers. Reading practices and communities across the British Empire, c. 1890-1930, thesis, Wellington 2012: University of Wellington.

- Littlewood, David: ‘Willing and eager to go in their turn’? Appeals for exemption from military service in New Zealand and Great Britain, 1916-1918, in: War in History 21/3, 2014, pp. 338-354.

- Malone, E. P.: The New Zealand School Journal and imperial ideology, in: The New Zealand Journal of History 7/1, 1973, pp. 12-27.

- Phillips, Jock: To the memory. New Zealand's war memorials, Nelson 2016: Patton & Burton.

- Ross, Kirstie: 'More than books tell.' Museums, artefacts and the history of the Great War, Newcastle upon Tyne 2017: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.