Introduction↑

In Japan, research on World War I was limited until a few years ago. As is often remarked, Japan suffered fewer war dead during World War I than it did during the Sino-Japanese War. With the exception of Frederick Dickinson, few historians have attempted a comprehensive analysis of Japan in the First World War.[1] Thus, how Japanese society and Japanese at the time made sense of World War I has not been systematically and comprehensively examined. As the centennial anniversary of World War I approached, however, growing numbers of Japanese historians turned to World War I.[2] Shin’ichi Yamamuro has described the conflagration as a “complex war”, requiring skillful Japanese diplomatic maneuvering between Britain, China, and the United States (U.S.).[3] Inoue Toshikazu has tied the war to the rise of mass culture in Japan.[4] Using excerpts from several papers that have recently been published, the current work surveys how Japanese made sense of the war.

Entry into World War I↑

When World War I began with the assassination in Sarajevo, draftees and volunteers famously remarked that the war would end soon after their arrival and that they would be home by Christmas time. Moreover, Japan was far from the European front, so the general thinking in Japan was how to obtain the maximum benefit from being involved in what was sure to be brief war in Europe.

On 7 August 1914, the British government asked Japan to help destroy German armored cruisers in Chinese waters. At the time, Japan was allied with Great Britain (the Anglo-Japanese Alliance), but the operative scope of the alliance was limited to East Asia, so Japan was not obligated to enter the war.[5] However, Foreign Minister Kato Takaaki (1860-1926) favored entering the war to pursue Japan’s national interests. As a result of its victory in the Russo-Japanese War, Japan secured interests in South Manchuria from Russia, but the leases on which those interests were based were due to expire around 1923. By entering the war, Japan could secure German interests in Shandong Province and return them to China, as Kato reasoned. As compensation, Japan would be able to extend the leases to its interests in South Manchuria.

In contrast, Yamagata Aritomo (1838-1922), an elder statesman and field marshal, opposed entering the war to fight against Germany.[6] The Imperial Japanese Army had sympathy for imperial Germany, and Yamagata himself considered the war in Europe to be evenly matched. Ultimately, however, Kato displayed strong leadership and he overpowered Yamagata. On 23 August 1914, the Japanese government declared war on Germany.

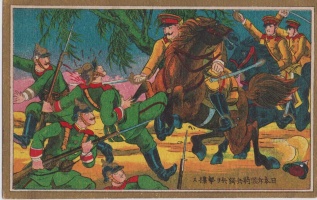

From the end of September to October 1914, the Imperial Japanese Navy occupied Germany’s South Pacific islands.[7] The Imperial Japanese Army besieged Qingdao City in Jiaozhou Bay in China’s Shandong Province, and the city fell on 7 November 1914.[8] With these acts, combat operations by the Japanese military during World War I in fact concluded.

↑

At the beginning of the war, few people believed that the war in Europe would be such a protracted conflict. Terauchi Masatake (1852-1919) was governor-general of Korea and would later become prime minister of Japan several years into the war. As of August 1914, Terauchi expected that “It [the war in Europe] will probably go on for at least 6 months.”[9] Conversely, most Japanese at the time did not think that the war in Europe would last for six months.

As mentioned earlier, the leases on which Japanese interests in South Manchuria were based were due to expire. Against this backdrop, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs assembled demands from the army and navy and presented twenty-one demands to the Chinese government in December 1914 after the fall of Qingdao.[10] The Chinese government strongly objected, and Sino-Japanese negotiations broke down. Ultimately, the Japanese government issued an ultimatum in May 1915, and the Chinese government agreed to sixteen of the Twenty-One Demands (Japan’s “desires,” i.e. the seven demands in group 5, were excluded). The Twenty-One Demands spurred a boycott of Japanese goods in China and also further tarnished the American view of Japan since the U.S. was critical of Japan’s foray into China.

Although Japan did in fact participate in World War I, hostilities in Asia had essentially ended after the Japanese military occupied German interests in Shandong Province and Germany’s South Pacific islands at the start of the war. Given that situation, whether or not to accede to requests for weapons from the Allies and requests that troops be sent to the European front was determined by balancing Japan’s standing as one of the Allied Powers and the extent of its commitment.

The Imperial Japanese Army opposed deploying troops. Viewing itself as a “self-defense force” based on conscription, the Japanese military saw deploying troops to Europe as extremely costly with little benefit. The Imperial Japanese Army did not ultimately deploy troops to the European front.[11] On the other hand, the Japanese navy agreed to send a special squadron to the Mediterranean from the perspective that the considerable shipping Japan was contributing to the war effort in Europe was being threatened by German submarines. Ultimately, Japan dispatched one cruiser and twelve destroyers.

Media Coverage of the First Half of the War↑

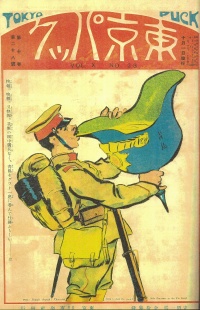

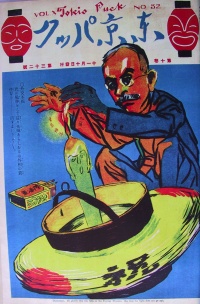

Wartime experiences of soldiers have a profound influence on public recollections after a war, and the home front has particular experiences in conjunction with total warfare. During World War I, Japan had far fewer of those experiences than Europe. When war broke out in Europe, however, Japanese publishers immediately began to publish pictorial magazines covering the war, and newspapers often featured articles reporting on the war in Europe with photographs.[12] Moreover, movie theaters often showed news reports on the war. Media heavily emphasized the fact that Japan was also a belligerent, which meant that it would actually be engaging in hostilities and suffering casualties.

The magazine Accounts of the War in Europe was published by Hakubunkan from August 1914-June 1917. Hakubunkan had been successful with its publication of accounts from the Sino-Japanese War and the Russo-Japanese War, so Accounts of the War in Europe can be seen as a publication with some degree of influence on the general understanding of World War I. Here, the magazine’s coverage of World War I will be summarized in three phases.[13]

The first phase of coverage of World War I by Accounts of the War in Europe was marked by 1914. As could be expected, articles at the time were mainly about the Japanese military’s involvement in the Siege of Qingdao. In particular, there was a debate as to whether or not Japan should return Qingdao and Jiaozhou Bay, which the Japanese military had occupied, to China in accordance with the written ultimatum Japan had issued to Germany. Overall, there was considerable debate as to whether Japan should use the occupation of Qingdao to expand its interests. Quite a few articles reported on the war in Europe. Since the war had just started, however, most of the articles were synopses or brief descriptions of the status of the war or conditions in different countries at the start of the war and soon afterwards. These fragmentary reports featured articles, photographs, and sketches highlighting the barbarism and cruelty of the Imperial German Army, which was generally in line with the Allied Powers’ view of the war. And Japan, of course, was one of the Allied Powers.

The second phase of coverage of World War I by Accounts of the War in Europe began after 1915. Fighting by the Japanese military had essentially ended, so articles mainly conveyed aspects of the war in Europe. During this phase, the war had finally expanded to a global scale, and occasional photographs and articles indicated that the war involved the mobilization of both imperial and colonial troops. Numerous photographs and articles also featured new weapons such as submarines, dirigibles, airplanes, and poison gas. In particular, photographs and frontispieces depicting poison gas attacks were, along with commentary, intended to depict the Imperial German Army’s disregard for the laws of war. Moreover, increased mobilization for war was evident in numerous frontispieces and articles regarding the mobilization of women. Thus, numerous articles conveyed the new aspects of war, i.e. a world war. That said, few editorials at the time, less than a year and a half after the start of the war, were describing the essence of modern warfare as “total war”.

Media Coverage of the Second Half of the War↑

As the war entered its second half, the essence of the war was seen as total war. An increasing number of editorials contended that Japan had to industrially mobilize to survive total war in the future.

The third phase of coverage of World War I by Accounts of the War in Europe was marked by the start of the Battle of Verdun in February 1916. During this major offensive and mass slaughter, Accounts of the War in Europe still featured articles about new weapons that had made huge advances, such as airplanes. In this third phase, numerous editorials increasingly analyzed the war in Europe from the perspective of “industrial mobilization”. As an example, Uemura Ryosuke (1878-?), an artillery officer, authored articles describing various aspects of the war. Lessons drawn from the war were not limited to “industrial mobilization”. A contrasting lesson drawn from the war was the concept of “national unity”. The concept of “national unity” stressed the need to mentally and physically unite as a nation in peacetime in order to win a war.

A look at media other than Accounts of the War in Europe reveals the widespread publication of “discussions of what to do after the war ends” starting in the latter half of 1916. In every field, including diplomacy, economics, industry, education, society, and family life, commentators began making postwar predictions and demanding corresponding policies. In the area of economics in particular, many commentators predicted Japan would be swept up in a fierce “economic war” with countries in Europe and the U.S. after the Great War. The U.S. was expected to expand into China, and the U.S. and Japan were expected to clash over the Chinese market and resources.

Thus, a wide range of Japanese, i.e. some intellectuals and the new urban and rural middle class, indirectly “experienced” the war in Europe through the media. In addition, the general public realized that warfare had now become total as a result of the Great War.

Acceptance of the Concept of “Total Mobilization”↑

When the war broke out, the Japanese military, and especially the army, endeavored to ascertain the status of the war by having military attachés and military observers actively collect, research, and report information regarding the war. In addition, articles based on that information became available to military personnel. This led to the belief that a future war, i.e. a war after World War I, would have to be fought as a total war. As a result, the perceived need to prepare for total war and to establish a system of total mobilization gradually spread in the latter half of the war.

As an example, Uemura Ryosuke stated in the December 1916 issue of Accounts of the War in Europe that, “In light of the state of the fighting in Europe, the general public is now aware of the fact that the resupply of a country’s weapons and ammunition is a crucial issue that decides the outcome of a war. The crux of this issue appears to be the quantity and supply of raw materials.” Uemura discussed establishing a system to stockpile and secure strategic resources. This proposal was based on an example of the increased need for ammunition. Over a thirteen-day period in the Battle of Mukden during the Russo-Japanese War, the Japanese military fired about 270,000 shells, while in the Champagne Offensives, which were two fierce battles during the First World War, the French army fired about 2.3 million shells, or almost ten times as many.[14]

In addition, many political elites embraced the concept of total war as a result of World War I. As an example, the elder statesman Yamagata Aritomo wrote in a letter in October 1917 that “The people must strive to come together as one by relying on class and national unity.” Yamagata was aware that warfare had entered the stage of total war. In addition, Inukai Tsuyoshi (1855-1932), leader of the Constitutional Nationalist Party, stated at a party convention in January 1918 that “Every man in the country is a soldier. Every factory in the country is a munitions factory.” Inukai argued that universal conscription and industrial mobilization needed to be promoted on the basis of economic rationalism. During the Terauchi cabinet, Nishihara Kamezo (1873-1954) and Finance Minister Shoda Kazue (1869-1948) busily worked to make a series of loans, the Nishihara Loans, to the government of warlord Duan Qirui (1865-1936) in China. Nishihara and Shoda wanted to forge economic ties with China as a source of resources in order to prepare for total war in the future.[15]

The Start of the Legal Underpinning for Industrial Mobilization↑

An Ad Hoc Naval Investigative Commission was created within the Ministry of the Navy in October 1915, and an Ad Hoc Military Investigative Commission was created within the Ministry of the Army in December of that year. After that, military leaders sensed the need to enhance national defense and prepare for industrial mobilization in order to win a total war.[16] In addition, the General Staff Office of the Imperial Japanese Army drafted reports such as the “Discussion of the Need for a Total Mobilization Plan” (September 1917) and “Defensive Resources of the Empire” (August 1917). These reports presented the concept of establishing a system of industrial mobilization under military leadership and expanding into the Eurasian continent in order to secure resources.[17]

In preparation for the Siberian Intervention by the imperial army, Chief of Staff Uehara Yusaku (1856-1933) cited the need for legislation regarding military supplies. As a result, the Munitions Industries Mobilization Act was enacted under the Terauchi cabinet in April 1918. This law provided for the management and administration of munitions factories and the conscription of workers during wartime as well as inspections of factories and protection and development of munitions industries during peacetime. Moreover, the Munitions Bureau was created under the auspices of the prime minister to oversee those operations. The Munitions Bureau was Japan’s first agency integrating all inspections related to total war. However, the various inspections and encouragement of munitions industries under the Munitions Industries Mobilization Act were limited to “wartime”, so the law was put into action during the Second Sino-Japanese War about twenty years later. In addition, the draft of the law was prepared in a short amount of time, so it had flaws and faults.[18] In other words, creating a system for industrial mobilization remained one of the foremost issues for Japan during the interwar years.

After the War↑

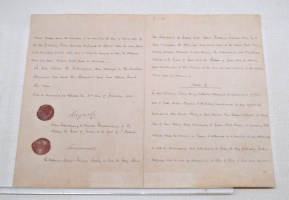

The Great War ended in November 1918; in January of the following year, a peace conference was held in Paris. The Japanese government sent a delegation like the twenty-six other countries did. Makino Nobuaki (1961-1949), the de facto head of the delegation, and the first section of the Political Affairs Bureau of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs that backed him, actively responded to the “new diplomacy”[19] advocated by U.S. President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924), and they sought to revise the “militaristic and aggressive policies” of the past towards China.[20] In contrast, Ito Miyoji (1857-1934), a privy councilor who was politically allied with Terauchi during the Terauchi cabinet, opposed the League of Nations touted by Wilson, viewing it as a type of political union. Prime Minister Hara Takashi (1856-1921) had long viewed alignment with the U.S. as essential. He saw international cooperation (centering on alignment with the U.S.) as “the way” of the world, and he ultimately overpowered Ito. Most important, a majority of Japanese statesmen viewed the First World War as the start of a new level of Japanese responsibility on the world stage. As Japan’s plenipotentiary to Paris, Saionji Kinmochi (1849-1940) remarked in 1919,

In the 1920s, the Japanese government placed international cooperation at the heart of its foreign policy.

Following the Great War, Japanese society widely shared the perception that the world had now transitioned into an era of total war. Following wartime Japanese and American economic growth, Japanese statesmen championed industrial mobilization during the interwar years. In 1927, Tokyo established the Resources Bureau, reflecting a convergence of civilian and military thinking in accordance with global trends. The Second Sino-Japanese War started in 1937. Civilian and military authorities competed for leadership of the system for industrial mobilization until the Resources Bureau was progressively absorbed into the Cabinet Planning Board.[22]

In short, interwar Japan faced two major trends as a result of countries participating in the Great War: international cooperation and preparing for industrial mobilization.

Conclusion↑

What sort of experience was World War I for Japan? Contrary to earlier dismissals, scholars now increasingly recognize the centrality of the Great War to Japan’s 20th-century experience. For example, Frederick Dickinson stresses that “just as Perry’s introduction of modern imperialism to Japan invited the creation of a modern nation-state, the First World War spurred the construction of what contemporaries referred to as the ‘New Japan’.”[23] Dickinson has laudably accentuated key Japanese contributions to the construction of a new global infrastructure for peace after 1918 – Japan’s participation in the Paris Peace Conference, League of Nations, and numerous affiliated organizations, arms reductions, and global trade. During the First World War, Japanese subjects for the first time came to feel a stake in global affairs. The Great War, in other words, established the foundations of Japan as a global power, with which we are very familiar today. On the other hand, Japan, which had no experience of total war in World War I, achieved heavy and chemical industrialization during the late interwar period. And Japan established the wartime regime, “1940 System”, to enable the government to carry out a total war. This system determined the key characters of the post-war Japanese economy.[24]

Isao Chiba, Gakushuin University

Section Editor: Frederick Dickinson

Notes

- ↑ See Dickinson, Frederick R.: War and National Reinvention. Japan in the Great War 1914-1919, Cambridge; London 1999. As indicated by the name, this research describes how the Meiji state that was created by the Meiji Restoration in the 19th century was reinvented by World War I.

- ↑ See Yamamuro, Shin’ichi et al. (eds.): Gendai no kiten daiichiji sekaitaisen [World War I as the Starting Point of the Modern Age], Sekai sensō [World War], volume 1, Tokyo 2014.

- ↑ See Yamamuro, Shin’ichi: Fukugō sensō to sōryokusen no dansō. Nihon ni totte no Daiichiji Sekai Taisen [Faultline between Complex and Total War. World War I from the Perspective of Japan], Kyoto 2011.

- ↑ See Inoue, Toshikazu: Daiichiji Sekai Taisen to Nihon [The First World War and Japan], Tokyo 2014.

- ↑ Unless otherwise noted, see Chiba, Isao: Kyūgaikō no keisei. Nihon gaikō 1900-1919 [The Formation of Old Diplomacy, Japanese Diplomacy 1900-1919], Tokyo 2008.

- ↑ Not all elder statesmen opposed entering the war. From his sickbed at the time, Inoue Kaoru (1836-1915) favored entering the war, viewing the Great War as “divine aid of the new Taisho era for the development of the destiny of Japan."

- ↑ For activities of the Imperial Japanese Navy during World War I, see Hirama, Yōichi: Daiichiji sekaitaisen to Nihonkaigun. Gaikō to gunji to no rensetsu [World War I and the Japanese Navy. The Connection Between Diplomacy and Military Affairs], Tokyo 1998.

- ↑ For the German-Japanese War involving Qingdao, see Saito, Seiji: Nichidoku Qingdao senso [The German-Japanese War in Qingdao], Tokyo 2001.

- ↑ Terauchi Masatake to Akashi Motojiro, 22 August 1914, Papers of Akashi Motojiro in the National Diet Library, Tokyo.

- ↑ Over the past few years, detailed research on the Twenty-One Demands has emerged. See Naraoka, Sōchi: Taika nijuikkajo yokyu towa nandattanoka. Daiichiji sekaitaisen to nichu tairitsu no genten [What Were the Twenty-One Demands to China? The First World War and the Starting Point of Sino-Japanese Confrontation], Nagoya 2015.

- ↑ See Inoue, Daiichiji 2014.

- ↑ How mass media in Japan accepted and viewed the Great War has seldom been studied. Although some research has been conducted, it either focuses on entry into the war or the Paris Peace Conference or it concentrates on certain media, such as political party newspapers. For exceptions to this, see Schmidt (2014), who focused on widespread publication of “discussions of what to do after the war ends,” and Kobayashi (2008), who analyzed coverage of the war in Accounts of the War in Europe, a pictorial magazine from Hakubunkan. Schmidt, Jan: Nihon ni okeru 'sengo-ron' [‘Postwar Discourses’ in Japan], in: Yamamuro, Shin’ichi et al. (eds.): Gendai no kiten daiichiji sekaitaisen [World War I as the Starting Point of the Modern Age], Sekai sensō [World War], volume 1, Tokyo 2014; Kobayashi, Hiroharu: Soryokusen to demokurashi. Daiichiji sekai taisen – shiberia kansho senso [The Total War and Democracy. World War I - Siberian Intervention War], Tokyo 2008.

- ↑ The current work relies on valuable research by Kobayashi, Soryokusen 2008, who analyzed Accounts of the War in Europe since the magazine covered most of World War I.

- ↑ Koketsu, Atsushi: Kokka sodoin taisei no Jidai. Nihon Rikugun no Kokka sodoin koso [A Look at Total Warfare. The Imperial Japanese Army’s Concept of Industrial Mobilization], Tokyo 1981, p. 18.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 19-22.

- ↑ See Ogawara, Masamichi: Senji taisei to Gyosei no Tyuousyukenka [Japan’s Wartime Government and the Centralization of Power in the National Government], in: Kasahara, Hidehiko (ed.): Nihon Gyoseishi [Japanese Government History], Tokyo 2010.

- ↑ Koketsu, Kokka 1981, pp. 27-40.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 47-53.

- ↑ For Japan’s response to Wilson’s foreign policy, see Takahara Shusuke: Uiruson Gaikō to Nihon [Wilsonian Diplomacy and Japan], Tokyo 2006.

- ↑ Aspects of Common Problems that Need to be Considered, Makino Nobuaki Kankei bunsho [Papers of Makino Nobuaki], National Diet Library, Tokyo.

- ↑ Quoted in Dickinson, Frederick R.: World War I and the Triumph of a New Japan, 1919-1930, Cambridge; New York 2013, p. 71.

- ↑ For civilian leadership in industrial mobilization, see Mori, Yasuo: Kokka sodoin no Jidai [The Age of Industrial Mobilization], Nagoya 2020.

- ↑ See Dickinson, World War I 2013, p. 6.

- ↑ See Yukio, Noguchi: 1940nen taisei. Saraba senjitaisei [1940 System. Farewell "Wartime Economy"], Tokyo 1995.

Selected Bibliography

- Chiba, Isao: Kyūgaikō no keisei. Nihon gaikō 1900-1919 (The formation of old diplomacy. Japanese diplomacy 1900-1919), Tokyo 2008: Keisō Shobō.

- Dickinson, Frederick R.: War and national reinvention. Japan in the Great War, 1914-1919, Cambridge 1999: Harvard University Press.

- Dickinson, Frederick R.: World War I and the triumph of a new Japan, 1919-1930, Cambridge; New York 2013: Cambridge University Press.

- Dickinson, Frederick R.: Tragic war, lasting peace. Japan and the construction of global peace 1919–1930, in: Minohara, Tosh / Dawley, Evan (eds.): Beyond Versailles. The 1919 moment and a new order in East Asia, Lanham 2021: Lexington Books, pp. 247-270.

- Hirama, Yōichi: Daiichiji sekaitaisen to Nihonkaigun. Gaikō to gunji to no rensetsu (World War I and the Japanese Navy. The connection between diplomacy and military affairs), Tokyo 1998: Keiō gijuku daigaku.

- Inoue, Toshikazu: Daiichiji Sekai Taisen to Nihon (The First World War and Japan), Tokyo 2014: Kōdansha.

- Kobayashi, Hiroharu: Soryokusen to demokurashi. Daiichiji sekai taisen – shiberia kansho senso (The total War and democracy. World War I – Siberian Intervention War), Tokyo 2008: Yoshikawa Kobunkan.

- Koketsu, Atsushi: Kokka sodoin taisei no Jidai. Nihon Rikugun no Kokka sodoin koso (A look at total warfare. The Imperial Japanese Army’s concept of industrial mobilization), Tokyo 1981: San-ichi Publishing.

- Mori, Yasuo: Kokka sodoin no Jidai (The age of industrial mobilization), Nagoya 2020: Nagoya University Press.

- Naraoka, Sōchi: Taika nijuikkajo yokyu towa nandattanoka. Daiichiji sekaitaisen to nichu tairitsu no genten (What were the twenty-one demands to China? The First World War and the starting point of Sino-Japanese confrontation), Nagoya 2015: Nagoya University Press.

- Ogawara, Masamichi: Senji taisei to Gyosei no Tyuousyukenka (Japan’s wartime government and the centralization of power in the national government), in: Kasahara, Hidehiko (ed.): Nihon Gyoseishi (Japanese Government History), Tokyo 2010: Keio University Press.

- Saito, Seiji: Nichidoku Qingdao senso (The German-Japanese war in Qindao), Tokyo 2001: Yumani shoten.

- Schmidt, Jan: Nihon ni okeru 'sengo-ron' (‘postwar discourses’ in Japan), in: Yamamuro, Shin'ichi / Akeo, Okada; Takashi, Koseki et al. (eds.): Gendai no kiten daiichiji sekaitaisen (World War I as the starting point of the Modern Age), Sekai sensō (World War), Tokyo 2014: Iwanami Shoten, pp. 155-178.

- Schmidt, Jan: Daiichiji taisenka Nihon no Senso hodo to 'Sengo' ron (Japanese reporting on World War Ⅰ and 'postwar' thought. Discourse on total war and the future for Japan), Tokyo 2014: Asteion.

- Takahara, Shusuke: Uiruson Gaikō to Nihon (Wilsonian diplomacy and Japan), Tokyo 2006: Sobunsha.

- Yamamuro, Shin’ichi: Fukugō sensō to sōryokusen no dansō. Nihon ni totte no Daiichiji Sekai Taisen (Faultline between complex and total war. World War I from the perspective of Japan), Kyoto 2011: Jinbun shoin.

- Yamamuro, Shin’ichi / Okada, Akeo / Koseki, Takashi et al.: Gendai no kiten daiichiji sekaitaisen (World War Ⅰ as the starting point of the Modern Age), Sekai sensō (World War), Tokyo 2014: Iwanami Shoten.

- Yukio, Noguchi: 1940nen taisei. Saraba senjitaisei (1940 system. Farewell 'Wartime Economy'), Tokyo 1995: Toyo Keizai Shin’posha.