Introduction↑

There has been little research on the First World War and its effect on Japanese literature until very recently. Before anything else, we have to take into account that the Japanese media went through massive changes at that time.

The circulation of magazines and newspapers increased dramatically, and the First World War was widely reported there. Erich Maria Remarque (1898-1970) also became a phenomenon in Japan. His novel All Quiet on the Western Front (1928) became a war drama and gained popularity in Japan.[1] The pageant movement that had taken place in the United States and Europe after the First World War was introduced to Japan by author Tsubouchi Shoyo (1859-1935).[2] All of this involved the media. In Japan, it was Natsume Soseki (1867-1916) who was most aware of the war in the media.[3] Soseki wrote about his media days in the essay The Inside of the Glass Door (Garasudo no uchi, 1915) and about the First World War in the essay Tentoroku (1916), a full-scale war theory that discusses militarism and individualism. Through the media, Japan consumed reports regarding the war “across the sea”. This was a tumultuous time for Japan when one considers the short period of time between the conclusion of the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905) and Japanese participation in the First World War, as well as the rapidity with which a new round of aggression began between Japan and the United States of America in the Pacific. Therefore, while there is a tendency to think that the First World War had little to do with Japan, East Asia was in the midst of these wars which followed rapidly on from one another.

Japanese Authors in France during the First World War↑

At that time, many Japanese people were on the ground in Europe and writing of their experience. The Japanese author Shimazaki Tōson’s (1872-1943)[4] series called News from France (Furansu dayori, 1913-1915) is an example. Tōson moved to France in 1913. He also wrote a book against the backdrop of his stay in France called New Life (Shinsei, 1919) in which he described his well-known sexual relationship with his niece. After his arrival in France, the war broke out and a critical mood quickly emerged in Paris. After returning to Japan, he became a nationalist and completed the novel Before Dawn (Yoakemae, 1935). The socialist Komaki Ōmi (1894-1978)[5] had also been confronted with this war, which led him to write the book Other Countries’ Wars (Ikoku no sensō, 1930). Komaki returned to Japan right after the war and published the first issue of the magazine The Sower (Tane maku hito, 1921) and introduced the Third International[6] to Japan. In this way, the authors who encountered the First World War and wrote of their experiences began the ideological preparation for the next world war.

The Link Between War Theory and the Philosophy of Life↑

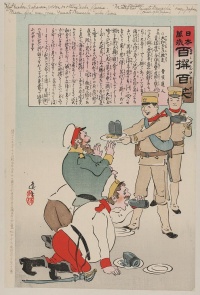

The First World War was depicted in the Japanese media in an abstract and indifferent way, but unlike during the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) and the Russo-Japanese War, there was less acrimony, and therefore, the war was employed in a metaphorical sense in many war debates about the benefits of war generally. More importantly, at that time the philosophy of life and the war theory were linked. An important critic was Nakazawa Rinsen (1878-1920).[7] He introduced the philosophy of Henri-Louis Bergson (1859-1941)[8] to Japan. The term élan vital (fullness of life) was integrated into the language and used to talk about the world war through the lens of Bergson’s philosophy. In his article, Bergson’s View on War and Contemporary Civilization (Beruguson no sensō oyobi gendaibunmeikan, 1916), he presented the viewpoint of war as a vital phenomenon.

A New Perspective on “Disabled Soldier Novels”↑

Next, attention should be given to the fact that World War I occurred during the aftermath of the Russo-Japanese War. Anti-military novels appeared which revealingly described inside information on the realities of the army. The famous Japanese naturalistic writer Tayama Katai (1872-1930)[9] experienced the Russo-Japanese War as the head of the unit of military cameramen. His famous long novel on a deserter, A Soldier Shot to Death (Ippeisotsu no jūsatsu, 1917), was based on this experience. During this period there were also many “disabled soldier novels” depicting the stories of injured soldiers after the Russo-Japanese War. Nakamura Seiko’s (1884-1974)[10] The Director of the Disabled Soldiers’ Home (Haihei inchō, 1916) and Kaneko Yōbun’s (1894-1985)[11] The Last Train that Picked Up Disabled Soldiers (Haihei wo noseta aka densha, 1922) are two examples. The grotesque portrayal of these soldiers is part of a collection of works which shook the peaceful image of the Taisho period.

The Siberian Expedition and Literature↑

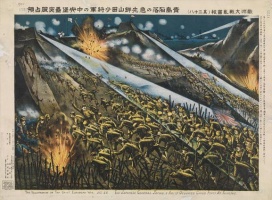

In terms of the impact of the First World War, a problem that cannot be overlooked is the Siberian expedition.[12] This saw more than 70,000 Japanese soldiers dispatched; the scale of which can surely be called a “war”. As for the purpose of this expedition, this is still not clear. Miyazawa Kenji (1896-1933)[13] was a famous writer who created many fairytale novels. Amongst those works is one, The Crow and the Big Dipper (Karasu no hokuto shichisei, 1924), that calls to mind the First World War. It is a work depicting the decisive battle between a volunteer armada of crows and mountain crows. After burying the remains of his enemy, the prayer of the commanding officer of the birds goes as follows: “Soon there will be this world, where we don’t have to kill the enemy”. This statement is also repeated in, for example, The Night of the Milky Way Railroad (Ginga tetsudō no yoru, 1927). It would be fair to say that it is characteristic of Miyazawa Kenji’s recurring theme of self-sacrifice. This is a reflection of the Japanese spirit of war. Another example is Kuroshima Denji’s (1898-1943)[14] A Flock of Swirling Crows (Uzumakeru karasu nomure, 1928). It focuses on Japanese soldiers who had been stationed in Siberia for more than two years and were completely exhausted by garrison life. The superior dispatches the unit towards the defense of a partisan hideout. The unit gets lost in a snow field and one by one the members of the troop collapse on their way and die. This novel is a proletarian literary work depicting the last days of these miserable soldiers’ lives. The image of these wandering soldiers really resembles the image of the Siberian expedition.

Accounts of Future Wars↑

Lastly, there was a perception that was widely present in literature of that time which centered on an oft-repeated idea, that – if a world war would happen again – the relationship between Japan and the US would be a criterion.

We will now turn to a discussion on the topic of accounts of future wars (science fiction) written during World War I, with Mizuno Hironori’s (1875-1945)[15] The Next War (Tsugi no issen, 1914) being a primary example. Mizuno was an officer in the navy. In 1916 he was determined to carry out military research about the First World War and applied for a two-year period of study abroad to visit the United States and European countries. He even visited the forts near Verdun and was an eyewitness to the realities of modern warfare. The Next War is a novel set in the Pacific depicting naval power. The conception of this novel is thought to come from Homer Lea’s (1876-1912)[16] novel The Valor of Ignorance (1909). What should be kept in mind is that these predictions about the future had a considerable influence on public opinion about the Japanese-American relationship. In this way, there is a concrete relationship between Japanese literature and the First World War. First, the world war was consumed as a phenomenon in the Japanese media. The concrete manifestation of this was the war theory and the popularity of Erich Maria Remarque. Second, East Asia was entering an age of wars and Japanese literature at that time should be considered in this context. Further to this, when considering the works of Mizuno Hironori it is certain that literature played a role in preparing for the next world war.

Hiroaki Nakayama, Tokushima bunri daigaku

Section Editor: Jan Schmidt

Notes

- ↑ Erich Maria Remarque was a 20th century German novelist. His landmark novel All Quiet on the Western Front (1928), about the German military experience of the First World War, was an international best-seller which created a new literary genre, and was subsequently made into the film All Quiet on the Western Front (1930). Details of the Remarque boom in Japan are given in Nakayama, Hiroaki: Daiichiji Taisen no Kage. Sekai Senso to Nihon Bungaku [The Shadow of World War I. World War and Japanese Literature], Tokyo 2012, pp. 182-209.

- ↑ Tsubouchi Shoyo was a Japanese author, critic, playwright, translator, editor, educator, and professor at Waseda University. Examples of his work are the criticism Shosetsu Shinzui [The Essence of the Novel, 1885], and the novel Tosei Shosei Katagi [Portraits of Contemporary Students, 1885]. For details of Shoyo's pageant movement, refer to Nakayama, Daiichiji Taisen no Kage 2012, pp. 157-181.

- ↑ Natsume Soseki was a Japanese novelist. He is best known around the world for his novels Kokoro, Botchan, I Am a Cat and his unfinished work Light and Darkness.

- ↑ Shimazaki Tōson was a Japanese poet and novelist who was active during the Meiji, Taisho and early Shōwa period. He established himself as one of the major proponents of naturalism in Japanese literature and was also part of the Meiji romanticism literary movement. The details of Shimazaki Tōson's experience in France are described in the following paper, in addition to Nakayama, Daiichiji Taisen no Kage 2012. Rabson, Steve: Shimazaki Toson on War, in: Monumenta Nipponica 46/4 (1991), pp. 453-481.

- ↑ Komaki Ōmi promoted his pacifist and communist ideas through essays and poems. He was also a translator of French literature during the Taisho and Shōwa period.

- ↑ This was an international communist organization founded by Vladimir Lenin in 1919, also known as The Communist International or Comintern. It was formed to unite communist groups of various countries. The association was dissolved in 1943.

- ↑ Nakazawa Rinsen was an essayist who specialized in the history of civilizations. He published essays about several philosophers including Bergson and Nietzsche. He also wrote about occidental culture and Russian literature.

- ↑ Bergson was a French philosopher who coined the term élan vital. This is the vital force or impulse of life responsible for evolution present in all organisms. This philosophy was incorporated by the French army during the First World War by arguing that the spirit of the soldier was more important than weapons to win the fight.

- ↑ Tayama Katai was a Japanese author who established the naturalistic “I-literature” (watakushi shosetsu) in Japan and wrote about his experiences during the Russo-Japanese War.

- ↑ Nakamura Seiko was a translator of French novels who later became an author himself. He is thought to be one of the introducers of French literature to Japan. In 1956 he was given the prestigious title of Person of Cultural Merit (bunkakorosha).

- ↑ Kaneko Yōbun was a fellow founder of Tanemaku Hito, an influential Japanese socialist magazine. Later in his life he became a member of the socialist party in the Japanese House of Councilors.

- ↑ In public discourse, the reason for the Siberian expedition is often doubted. In reality, the purpose was to create a buffer state between communism and Japan. Further to this, the Japanese political and economic elite wanted to increase Japan’s circle of influence in East Asia.

- ↑ Miyazawa Kenji, besides being a devout Buddhist and social activist, was a poet and author of children’s literature intended to assist in moral education.

- ↑ Kuroshima Denji was an antimilitarist intellectual who expressed his ideas in proletarian anti-war literature.

- ↑ Mizuno Hironori was a military man who later became a military affairs critic. Several of his works predicted a war between Japan and the United States. He was also a supporter of international pacifism.

- ↑ Homer Lea was a geopolitical spokesman with a pronounced interest in Chinese affairs. He is further known for his speculations on a war between Japan and the United States.

Selected Bibliography

- Asada, Jiro (ed.): Senso to Bungaku Annai. Collection Senso to Bungaku (Guide war and literature), Tokyo 2013: Shyueisha.

- Katayama, Morihide: Mikanno Fascism motazaru kuni Nihon no Unmei (Unfinished fascism. Japanese fate a 'country without'), Tokyo 2012: Shinchosha.

- Komori, Youichi: Seikimatsu no Yogensha. Natsume Soseki (The end of century prophet. Natsume Soseki), Tokyo 1999: Koudansha.

- Kono, Kensuke: 'Sinsei' niokeru Senso. Shimazaki Toson no Sousaku to Kokumin Kokka (War in the 'new life.' Creation and the nation state of Simazaki Toson), in: Nihonbungaku 44/11, 1995, pp. 1-10.

- Kono, Toshiro: Daiichiji Sekai Taisen to Bundan (World War Ⅰ and Japanese literary circles), in: Kokubungaku 9/12, 1962, pp. 30-35.

- Nakayama, Hiroaki: Senkanki no 'Yoakemae'. (Interwar and 'before dawn.' World war as a phenomenon), Tokyo 2012: Soubunsha Shuppan.

- Nakayama, Hiroaki: Youkaisuru Bungakukenkyu. Simazaki Toson to Gakumonshi (Literary studies that dissolves. Shimazaki Toson and the history of literature research), Tokyo 2016: Kanrin Shobou.

- Nakayama, Hiroaki: Daiichiji Taisen no Kage. Sekai Senso to Nihon Bungaku. (The shadow of World War I. World war and Japanese literature), Tokyo 2012: Shinyōsha.

- Rabson, Steve: Shimazaki Toson on war, in: Monumenta Nipponica 46/4, 1991, pp. 453-481.

- Sato, Izumi: Soseki to Daiichiji Sekai Taisen (Soseki and World War Ⅰ), in: Anahorishu Kokubungaku, 2013, pp. 45-50.

- Yamamuro, Shin’ichi: Fukugō sensō to sōryokusen no dansō. Nihon ni totte no Daiichiji Sekai Taisen (Faultline between complex and total war. World War I from the perspective of Japan), Kyoto 2011: Jinbun shoin.

- Yatsu, Satoshi: Hagiwara Sakutaro "Tsukini Hoeru" to senso :Nichiro senso Taigyaku jiken sekaisenso to "Tsukini Hoeru" ki no Sakutaro ("Hagiwara Sakutaro's howling at the moon and war. The Russo-Japanese War. The high treason incident of 1910. World war and Sakutaro during the period of howling at the moon"), in: Modern Japanese Literary Studies 98, 2018, pp. 146-161.