Introduction↑

Austrian literature is a difficult term in the context of the First World War since it does not apply to any concrete, national identity but instead forms part of a long-established multinational or international culture. Thus, in contrast with other examples of European literature, Austrian literature can be described as “less centered, less stable, less consistent, more erratic, more frivolous, and potentially more liberated from convention”[1]. Various prominent writers fought in the trenches or produced propaganda in the War Archives (Kriegsarchiv). This meant that actual warfare found only little resonance in literature. This article provides an overview of (German-speaking) Austrian literature published by various authors from the multinational Austro-Hungarian monarchy, against the background of the Great War (i.e. during and immediately after the war, and at the end of the 1920s and beginning of the 1930s.) These were turbulent times in which the problems of war became foregrounded in political discourse. The article will then consider the military, propagandist and ideological involvement of writers in the war; the various concepts of war; expectations, fears, hopes and disappointments; reactions to the war in poetry, narrative prose, drama and journalistic texts; supportive stances towards the war; critical analyses and summaries of the event. The article is divided into four parts which include: literary documents of mobilisation and the heroically stylised narratives of the front; the depictions of the horrors and sacrifices made by the soldiers; texts dealing with the hinterland; and the delineation of the war’s effect on key figures in the First Austrian Republic.

The Adventure of War↑

Texts advocating the war were written not only by the writers who were employed by propaganda offices, but also by those who were engaged in combat on the frontline. Many writers were not immune to the collective enthusiasm for war and plunged themselves into a creative frenzy of producing patriotic literature. Richard von Schaukal (1874-1942) evokes in his Eherne Sonette 1914 (Bronze Sonnets 1914) and the Austrian Freude an den Waffentänzen (Pleasure in the Dances of the Weaponry) which tells the story of the war and the soldiers who readily submitted themselves to Wilhelm II, German Emperor’s (1859-1941) will. Von Schaukal evokes the age-old tradition of the warrior with his steed, sword and lance. Thus, his war poetry, written partly in aggressive tones, is a literary document that provides evidence of the militaristic spirit of the times and his poems were printed in newspapers and on postcards for propaganda purposes.

The writer and artist Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980), who was wounded during voluntary military duty, portrays himself at first as a proud cavalryman, hoping to overrun the enemy with flying colours through a swashbuckling battle that ends triumphantly to the sound of trumpets. His experiences as a victim of war would later be treated in his short story Jessica, which questions his previous gung-ho mentality and carefully portrays the fine divide between heroic impulse and the humiliation of being wounded — “Heldentod – ja! – aber nicht wie ein Wurm zertreten sein.”[2]

An ambivalent conceptualisation of war evinces itself in Rainer Maria Rilke’s (1875-1926) war-glorifying poem, Fünf Gesänge (Five Songs 1914), which forms part of the literary "call-to-arms" movement. Later, Rilke would distance himself from his work and refuse to make his opinion of war public. Not only is a “Kriegs-Gott” (“a god of war”) invoked in the Fünf Gesänge, the poem also argues for a moving away from the civilian world as imperative to the acquisition of an “eisernes Herz” (“iron heart”) and to fight “heilig gemeinsam” (“together and divinely”). However, Rilke’s literary contribution to the general enthusiasm for war also demonstrates a subtle trace of “Kampf-Schmerz” (“battle fatigue”) — a semantics of crisis that conflicts with its aggressive heroic discourses to foreground the fact that war requires not only heroes and victors, but also suffering and victims.

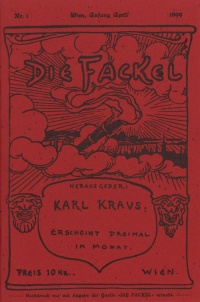

During the course of the war, further patriotic and chauvinistic poems were produced which celebrated a new sense of togetherness and called their readers to arms. In the case of the traditional and lyric poetry of Anton Wildgans (1881-1932), Anton Müller (1870-1939), also known as "Bruder Willram", Ottokar Kernstock (1848-1928), Peter Rosegger (1843-1918) or Richard Kralik (1852-1934) the war was celebrated as a “wundersames Menschenwerk”.[3] Hermann Bahr (1863-1934), an author of narrative prose, wrote Kriegssegen (The Blessing of War 1915) in which he positioned the war as a fight for all things Austro-German. Many Austrian writers volunteered or were ordered to join the War Archives and War Office (Kriegspressequartier) tasked with producing cultural and political propaganda for the Austro-Hungarian Empire which was commonly known as Heldenfrisieren (“fashioning heroes”). The most well-known of these writers was Hugo von Hofmannsthal (1874-1929) who defended the “österreichische Idee” (“Austrian idea”) in his literary and journalistic works, portraying the war as a cultural phenomenon and an opportunity for intellectual regeneration. Alongside Hofmannsthal, the following writers were also employed by the War Archives or War Office (Kriegspressequartier) at one time or another: Franz Blei (1871-1942), Egon Erwin Kisch (1885-1948), Stefan Zweig (1881-1942), Franz Theodor Csokor (1885-1969), Alfred Polgar (1873-1955), Felix Salten (1869-1945), Albert Paris Gütersloh (1887-1973), Karl Hans Strobl (1877-1946), Robert Musil (1880-1942), Leo Perutz (1882-1957), Franz Werfel (1890-1945) and Albert Ehrenstein (1886-1950). Rainer Maria Rilke was also employed for a short time along with many others. With a few exceptions, they were all swept up by the general enthusiasm for war in 1914 and their support was portrayed as a splendid drama by the militaristic attitudes expressed in their material.[4] Later, Karl Kraus (1874-1936) would use his satirical magazine, Die Fackel (“The Torch”), to roundly condemn this bellicose form of journalism during the war.

The massed ranks of armies and technological warfare (Materialschlachten) of the First World War left little room for individual heroic feats and the realisation of conventional, romanticised ideals. Nevertheless these ideals survived as elements of a glorious tradition and dictated common presumptions and literary images of military combat in Austria-Hungary. The ideal of the heroic individual did not simply disappear from narrative works on the war. Instead, it was perpetuated by legends fabricated after the event. Against the backdrop of the First World War, Austrian literature experienced a remarkable revival in militaristic, heroic and sentimental discourses. These discourses would be politically utilised in the First Republic and formed a central part of the rigorously disputed narrative of collective war memory. In a series of novels and autobiographical texts, combat in the Alps during the war in particular was transformed from a post-war standpoint into an epic struggle amongst chosen men, fighting it out in extreme conditions.

The autobiographical works of the former combatant Fritz Weber (1895-1972) — Das Ende einer Armee (The End of an Army 1931), Menschenmauer am Isonzo (The Wall of Men on the Isonzo 1931), Sturm an der Piave (Storm of the Piave 1931), Granaten und Lawinen (Grenades and Avalanches 1932), Feuer auf den Gipfeln (Fire at the Summits 1932) — glorify a fighting elite of Austro-German officers and soldiers or “Märtyrer der Beharrlichkeit” (“martyrs of determination”) as they were called. These martyrs were able to cope with all forms of industrialised warfare and modern technology, yet were also versed in traditional one-on-one combat with the enemy in a range of terrains and climates. The political implications of Weber’s project were apparent— the “great deeds” of those who fought in the Dolomites and at the Isonzo[5] were not merely to be remembered positively, but also relived. This is crucial when we take into account that the archaic notion of masculine militarism that was utilised in modern warfare to foster a sense of camaraderie. This machismo became relevant once more in the political context of the “kämpferische Welle” (“wave of aggression”) around 1930. Luis Trenker (1892-1990), who, like Weber, fought in the Dolomites, was another principal protagonist in the establishment of the myth of the mountainous warrior.

In 1931, Trenker published the popular patriotic novel Berge in Flammen (Mountains in Flames) which was later released as a very successful film also entitled “Berge in Flammen” (1931), which was directed by Karl Hartl (1899-1978) and Luis Trenker. The book’s main character is an Alpine war hero, a daredevil endowed with the key attributes of physical strength and cunningness. He performs a colossal yet risky deed which influences the whole course of the war and saves his comrades from certain death. The fact that the myth of the frontline soldier received particular adoration in the First Austrian Republic was due to works such as Bodo Kaltenboeck’s (1893-1939) war novel Armee im Schatten (Army in the Shadows 1932) and the German nationalist writer Karl Paumgartten’s (1872-1927), also known as Karl Huffnagl's Repablick: eine galgenfröhliche Wiener Legende (Republic 1924). Repablick was a salient example of völkisch narrative prose, which was characterised by aggressive, militaristic and racist tendencies. The tropes of the First World War and the symbolic figures of the former monarchy also played key parts in the political context of the Austro-fascist Corporate State (Ständestaat).

1934 saw the publication of Alexander Lernet-Holenia’s (1897-1976) novel Die Standarte (The Standard), which, albeit not entirely glorifying war, certainly rehabilitates the splendour of the military officer’s honour by recounting an adventurous, heroic version of war alongside a classic love story. The renowned play by Franz Theodor Csokor, 3 November 1918 (1936), demonstrates the writers’ propensity for mourning in literary works. This propensity was in relation to the decline of the Austro-Hungarian army and the ostentatiousness of the multinational Empire. On the whole, war was portrayed in the aforementioned texts as a sentimental and heroic form of adventure. No less a figure than Karl Kraus was required to correct this portrayal of war. In 1918, he describes the First World War as a “technoromantisches Abenteuer” (“techno-romantic adventure”) in which bravery has entered into a mismatch between technology and physical confrontation which rendered the sheer muscle of combatants obsolete. Kraus mocks the anachronistic ideology of courage that desperately held on to old values, ideals and ornaments. This was in spite of the fact that the god of war had descended from the machine and that the only thing that mattered to the author was the “Wirksamkeit der beiderseitigen Chemie.”[6]

Topographies of Horror↑

Karl Kraus’s revealing satire, Die letzten Tage der Menschheit (The Last Days of Mankind 1919, published in 1922) presented the Great War as a sort of panopticon and became one of the most important antiwar texts to ever be written in German. Die letzten Tage der Menschheit analysed the mind-set of the time, the idiocy and prejudice, the dominance of journalistic rhetorical phrases (e.g. “schwärzliche Magie” or “black magic”), the Austrian love of spectacle and ornamentation, the increasing madness and lack of collective imagination. Kraus argued that all these factors intended to chase humanity into “mass holes” (“Massenlöcher”). Here, war was characterised as an intellectual phenomenon — an alliance of ink, technology and death. A complementary image emerged from literary texts written by those who had fought on the frontline. Here, war was viewed as a technologically driven infernal scenario, or as a disastrous experience lodged in the memory of the individual who was reduced to the state of a puppet.

Symbolic of the horrors of war is the death of the Expressionist poet Georg Trakl (1887-1914) following a dreadful military manoeuvre at the “Todesmühle” (“Mill of Death”) near Grodek. His famous poem, Grodek (1914), encapsulates in dark, elegiac tones the terrors of a world in “schwarzer Verwesung” (“black decay”), inhabited by the ghostly presence of the “Geister der Helden” (“spectres of heroes”). The pacifist Albert Ehrenstein denounces in his poetry a god of war who spreads irrationality and madness, and for whom too many “Mußhelden” (“must-be heroes”) had served. In the Entwicklungsroman entitled Die große Phrase (The Great Phrase 1919) by the officer and writer Rudolf Jeremias Kreutz (1876-1949) who was captured by the Russian army, the war, which had been described both as wonderful and exciting, was transformed into a school of intolerable struggle and horror in which human life was sacrificed in an irresponsible, even senseless manner. The main character loses a leg in combat, leaves the frontline and, as a victim of war, becomes a fervent pacifist. He condemns the atavistic acts of violence and the criminality of the war, whilst revealing his commanders to be a set of mindless idiots. Like hundreds of other maimed veterans begging on the streets of Vienna, the disabled officer no longer has any hope of feeling at home in what is, nominally at least, still his home country. Drastic images of mutilated bodies in the Duell der Munitionsindustrien (Duel of the Munitions Industries) within Andreas Latzko’s (1876-1943) collection of short stories, Menschen im Krieg (People in a Time of War 1917). The pacifist writer fought on the Isonzo front and suffered a nervous breakdown. He describes war simply as slaughter and as a “Krüppel- und Leichenfabrik”[7] in which men are disfigured and traumatised. He argues that there is nothing heroic in the mindless drill, in the battles and marches, in the great dangers in which soldiers are placed, or in the chaos of warfare – it is merely a world of violence and death which exists only to humiliate those involved. Isolated in field hospitals and institutions for the disabled and psychotic, the deformed soldiers suffer flashbacks and are persecuted by images of death. The protagonist of the satirical novel Zacharias Pamperl oder Der verschobene Halbmond (Zacharias Pamperl, or The Displaced Crescent 1923) by Fritz Wittels (1880-1950) was a psychoanalyst who worked as a medical officer during the war and suffers from the condition termed "shell shock" in which he constantly perceives gunshots, sees disfigured corpses and finds himself unable to function during a period of convalescence in Vienna. Egon Erwin Kisch was another writer who had served at the frontline. In his war diary, Soldat im Prager Korps (A Soldier in the Prague Regiment 1922) which was better known under the title of the hugely successful later edition Schreib das auf, Kisch! (Write That Down, Kisch!), he documents his critical reflections during the different phases of his involvement in the War. The appalling images of injured men and chaotic, panic-like conditions on the battlefield Kisch recounts call into question the meaning of the War. Likewise, his own actions are never depicted as heroic deeds, but rather as coping strategies for fear, terror and despair. Kisch records relentlessly the increasing numbers of dead and wounded soldiers, as well as the feeling of misery, the officers’ arrogance and the privileged position of the Germans. Finally, he himself is injured and successfully plays out a simulated comedy. The ‘adventure’ described is thus stripped of all sentimentality, uncovering the inhuman aspects of militarism. Kitsch’s fellow author Franz Werfel also served on the Eastern front in the first half of the war and adopted a distinctly antimilitary position. As one of the first to do so, Werfel had taken issue with the “Wortemacher des Krieges” (“literary advocates of war”) in 1914. For this reason he wrote an anecdotal prose work, Ein Ulan (An Uhlan 1914), which depicted the ominous consequences of the madness of war and the paradoxical necessity of killing one’s own brothers in faith. These horrors of war were also addressed through the poetic elegy of a lost home in Werfel’s Barbara oder die Frömmigkeit (Barbara or Piety 1929). Full of disappointment, the novel’s hero watches as the spirit of militarism steadily gains momentum in post-war Austria once more.

Civilian Worlds and Dreams↑

The patriotic works of writers connected to the War Archives were not only aimed at improving the army’s morale, but were also intended to speak to and ideologically mold the home front. Hofmannsthal appealed to the “oberen Stände” (“upper classes”), forcefully promulgating the idea of togetherness and the “Bejahung Österreichs” (“Yes to Austria”) as a model of a future (European) order. Hofmannsthal emphasised the army’s prominent role within the State and promoted historical, patriotic awareness by editing a series of books entitled Österreichische Bibliothek (Austrian Library 1915-1917). Intended to educate the wider Austrian populace, the author’s line of argument was underpinned by a grandiose version of history while simultaneously creating legends and myths that submitted to a utopian imagination.

Anton Wildgans’s epic verse Kirbisch oder Der Gendarm, die Schande und das Glück (Kirbisch, or The Policeman, Shame and Fortune), published in 1927, shows the dysfunctional reality of the supposed solidarity and communal ethos of wartime society that Hofmannsthal originally espoused. The critical, satirical poem depicts moral decline in a provincial village whose inhabitants are shown to be a corrupt and opportunist group of people who do not care about the dreadful events taking place at the frontline. In Alfred Polgar’s short and critical prose commentaries on the war, Kleine Zeit (Small Times 1919) and the collection of stories Hinterland (1929)[8], the writer demonstrates the consequences of the mass conformity which produces “Antimenschen” (“anti-humans”). He also focuses on daily life in the hinterland, the "small" misery of an absurd war that was stylised as a ‘great age’. It is the ordinary people that fight at this other front — they go hungry in their perseveration, teetering between states of madness and despair. Clearly, this was no "great age" for Vienna — a hapless city full of military personnel who walk around wounded, ill and hungry. Polgar’s Wien, Dezember 1918 (Vienna, December 1918 1919) makes great use of irony, describing how debauchery and destruction annihilated this ‘great age’ and, furthermore, that “als Schlußeffekt, wird, soweit nur möglich, das Österreichische gestrichen, abgekratzt, liquidiert”[9]. Karl Kraus denounced the misery of the home front in much harsher, even aggressive tones. In his Die letzten Tage der Menschheit, a central part of war (particularly in urban Vienna) is portrayed as the ideological delusion of a civilian populace infected by propaganda slogans. Kraus further condemned the cynical nature of wartime politics and its ideological implications, the exploitation and repression of society by profiteers, extortionists and speculators making fortunes through “good war business”. Prophetically, Kraus also notes that the “tragic carnival” had caused seismic cultural changes — the trenches (Kraus uses the German “hineingewachsen”) have grown to engulf the home front.

Homecoming and Post-war Odysseys↑

Latzko’s short story Heimkehr (Homecoming 1917) portrays a veteran returning home to his wife bearing war wounds — he has a completely disfigured face as a consequence of undergoing various operations. After his neighbours fail to recognise him, he asks himself how his wife will react. His facial injuries mean his complete loss of social skills and the ability to compete with other men. Confronted with his wife’s infidelity, he then stabs her lover to death before he himself is killed by his wife. In numerous literary texts, traumatised veterans (Kriegsheimkehrer) turn into aggressors and even violent criminals. For instance, in Ernst Weiß’s (1882-1940) short story, Franta Zlin (1919), an emasculated victim of war describes the dangers of effeminising men and of male hysteria. Upon his return home with other failed war heroes and maimed veterans, the soldier experiences enormous difficulty trying to integrate once more into society, thus making civilian life (above all, work) and a sense of privacy (love and sexuality) extremely challenging, if not impossible. In Alfred Polgar’s prose work Rückkehr (Homecoming 1918), a veteran is faced with the loss of his honour and his “Manns-Besonderheit” (“special role as a man”) after he sees that women have successfully replaced men in a variety of different areas. This trope of discharged servicemen was of great concern to Austrian writers in the post-war era, particularly the sudden return of former officers and soldiers to civilian life, often with physical or mental impairments.

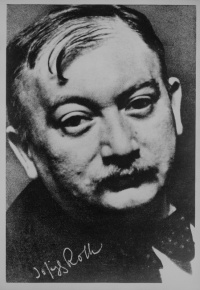

In the First Austrian Republic, a form of literature emerged which idealised uniforms and military symbols in a very nostalgic manner. Homeless veterans were viewed as undergoing existential crises. This aspect is central to the works of Joseph Roth’s (1894-1939) Das Spinnennetz (The Spider’s Web 1923), Die Rebellion (The Rebellion 1924), Die Flucht ohne Ende (The Flight without End 1927), Zipper und sein Vater (Zipper and His Father 1928), Rechts und Links (Right and Left 1929). These works depicted the end of the war as the beginning of an unreliable chaotic world void. The novel Wohin rollst du, Äpfelchen (Little Apple) by Leo Perutz which was published in installments in 1928, proved a huge success. It portrays an officer returning from a Russian Prisoner of War camp, obsessed by the thought of returning to Russia in order to take revenge. The oppressive realities faced by the Kriegsheimkehrer manifests in their "unsuitability" to civilian work and, indeed, civilian life itself. The loss of identity experienced by many led to a disorientation and regressive longing for a return to the ordered world of the military. Hofmannsthal’s "difficult" and traumatised veteran from his comedy Der Schwierige (A Difficult Man 1921) successfully reverts to a civilian way of life and returns to his wife who reveals herself to him in the trenches in a most mysterious manner.

Conclusion↑

Austrian literature concerning the First World War reveals heroic and patriotic, as well as pacifist and antimilitary overtones. On the one hand, it is concerned with the link between war and culture. On the other hand, following the strong Austrian tradition of language criticism, the war literature writes against the “Wortemacher des Krieges”[11] (Franz Werfel), it exposes the ideological phrase (Karl Kraus) and it characterises the war as an indescribable horror (or as Kreutz states, “um Schlagwörter willen”[12]). In general, the Great War acutely influenced the intellectual development and the literary production of many writers. Even writers like Franz Kafka (1883-1924) or Hermann Broch (1886-1951) who do not explicitly address the War in their works nonetheless depict the existential sensitivities of the era and discuss military and ethical problems as implications of the war.

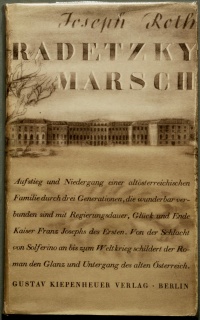

Compared to other examples of European literature, Austrian literature concerned itself less with the war itself rather than with the process of documenting the decline of the multinational state of Austria-Hungary. Following the events of 1918, it was also focused on upholding the memory of the dismantled Empire [represented by Joseph Roth’s Radetzkymarsch (Radetzky March 1932)]. The First World War meant the end of the apparatus of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy and the disappearance of a social capital — the habitus of the Austrian individual. The consequences of this cultural loss were felt on a variety of different levels. Thus, the undertone of Austrian literature, post-1918 in particular, can hardly be described as militaristic. Instead, it is characterised by a sense of disillusion caused by defeat at the hands of the Entente powers, coupled with the melancholic, nostalgic mourning of a “Welt von gestern”[13] (Stefan Zweig).

One of the central tropes of Austrian literature is the reference to the army and the military, in which the uniform is not simply a recurrent aesthetic or a fetish. Rather, the uniform functions metaphorically as an element of meaning and order in an otherwise chaotic world. (Bear in mind that many writers were officers or had experience in the military.) Here, the traditional Austrian system of hierarchy’s propensity for the theatrical and ceremonial plays a significant role. This sensuous culture of servility, which can be considered as particularly Austrian, defined literary discourses both during the War and in the post-war era. Even in texts evoking images of heroism, one frequently encounters references to the sweet tempered nature of Austrians and the artistic inclinations of the “dreamers” who became heroes in combat. Interracial tensions and rivalries are also portrayed, elaborating upon the key distinctions between the Prussian-German form of a harsh militarism of steel and the gentle nature of the Austrian mentality with its soft, light, opera-esque qualities. The discourse of "Austrianness" as a model for Europe, as well as the Austrian dissimilarity to Germany that stems from the outcome of the First World War, ostensibly overcame the peace-loving Austro-Hungarian monarchy in a wicked twist of fate. This twist led to its subsequent downfall. Austrian literature on the Great War forms part of a complex cultural paradigm in which individual texts possess direct historical relevance, participate in the culture of national memory, and reflect upon the far-reaching issue of the War in the historical, political and geographical context of the "Austrian".

Monika Szczepaniak, Kazimierz Wielki University

Section Editors: Gunda Barth-Scalmani; Oswald Überegger

Notes

- ↑ Beller, Steven: The Tragic Carnival: Austrian Culture in the First World War, in: Roshwald, Aviel/ Stites, Richard (eds.): European Culture in the Great War: The Arts, Entertainment and Propaganda, 1914-1918, Cambridge 1999, pp. 127-161, p. 128.

- ↑ “A hero’s death, yes! – But not to be trodden on like a worm.” Oskar Kokoschka: Jessica, in: Oskar Kokoschka: Spur im Treibsand. Geschichten, Zürich 1956, pp. 19-55, p. 45.

- ↑ “Miraculous feat of mankind”. Wildgans, Anton: Österreichische Gedichte, Leipzig n.d. [1915], p. 4. Wildgans wrote a whole series of poems in which he celebrates the “heiligen” (“holy”) war and the militaristic canon of virtues. His line of argument evinces definite German-national tones and he proclaims the "Austrian" to be an incarnation of the “deutschen Geistes” (“German mind”).

- ↑ Robert Musil, for instance, who fought at the front as a soldier himself, published an essay entitled Europäertum, Krieg, Deutschtum (1914) in which he enthused about war. Other texts which have been printed in various anthologies and journals glorify German and Austrian heroes (see Sauermann, Eberhard: Literarische Kriegsfürsorge. Österreichische Dichter und Publizisten im Ersten Weltkrieg, Vienna et al. 2000, pp. 225-246), depict a kind of sacrificial death for one’s country (ibd. 269-279), proclaim rallying calls and appeal to the warriors’ so-called manliness.

- ↑ For a nuanced view of gender myths following the First World War see Hofer, Hans-Georg: Nervenschwäche und Krieg. Modernitätskritik und Krisenbewältigung in der österreichischen Psychiatrie (1880-1920), Vienna et al. 2004, pp. 275-277.

- ↑ “Effectiveness of each side’s chemicals“. Kraus, Karl: Das technoromantische Abenteuer, in: Kraus, Karl: Schriften, ed. Christian Wagenknecht. Vol. 6: Weltgericht II, Frankfurt am Main 1988, pp. 86-91, p. 88.

- ↑ “Factory for producing cripples and corpses”. Latzko, Andreas: Menschen im Krieg, Zurich 1918, p. 137.

- ↑ It is worth noting that any of the stories in Hinterland were taken directly from the earlier edition, Kleine Zeit.

- ↑ “In a final climax, all things Austrian, as far as it goes, are being crossed out, scratched off and liquidated.” Polgar, Alfred: Wien, Dezember 1918, in: Polgar, Alfred: Kleine Schriften, Vol. 1: Musterung, ed. Marcel Reich-Ranicki. Reinbek nr, Hamburg 2003, pp. 85-88, p. 87.

- ↑ “In this we are operetta figures on our stages. Always elegant, always polite, always loveable, always dancing the waltz. One does not see the seriousness behind our smiling, polite bows. But this is what we want; we possess too much old culture.” Kaltenboeck, Bodo: Armee im Schatten. Die Tragödie eines Reiches, Vienna 1938, p. 164.

- ↑ “literary advocates of war”

- ↑ “For the sake of slogans”

- ↑ “Yesterday’s world”

Selected Bibliography

- Amann, Klaus: Der Anschluss österreichischer Schriftsteller an das Dritte Reich. Institutionelle und bewusstseinsgeschichtliche Aspekte, Frankfurt a. M. 1988: Athenäum.

- Amann, Klaus / Lengauer, Hubert (eds.): Österreich und der Grosse Krieg, 1914-1918. Die andere Seite der Geschichte, Vienna 1989: C. Brandstätter.

- Barker, Andrew: The First World War fiction of Andreas Latzko, in: Robertson, Ritchie / Timms, Edward (eds.): Gender and politics in Austrian fiction, Edinburgh 1996: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 100-117.

- Beller, Steven: The tragic carnival. Austrian culture in the First World War, in: Roshwald, Aviel / Stites, Richard (eds.): European culture in the Great War. The arts, entertainment, and propaganda, 1914-1918, Cambridge; New York 1999: Cambridge University Press, pp. 127-161.

- Buck, Theo: Dokumentartheater, 'Marstheater'. Zur Dramaturgie des Weltkriegs in Karl Kraus' Die letzten Tage der Menschheit, in: Schneider, Thomas F. (ed.): Kriegserlebnis und Legendenbildung. Das Bild des 'modernen' Krieges in Literatur, Theater, Photographie und Film, Osnabrück 1999: Universitätsverlag Rasch, pp. 881-896.

- Džambo, Jozo (ed.): Musen an die Front! Schriftsteller und Künstler im Dienst der k.u.k. Kriegspropaganda 1914 - 1918. Begleitband zur gleichnamigen Ausstellung, Munich 2003: Adalbert-Stifer-Verein.

- Hämmerle, Christa: 'Es ist immer der Mann, der den Kampf entscheidet, und nicht die Waffe…' Die Männlichkeit des k.u.k. Gebirgskriegers in der soldatischen Erinnerungskultur, in: Kuprian, Hermann / Überegger, Oswald (eds.): Der Erste Weltkrieg im Alpenraum. Erfahrung, Deutung, Erinnerung, Innsbruck 2006: Universitätsverlag Wagner, pp. 35-58.

- Hughes, John: Facing modernity. Fragmentation, culture, and identity in Joseph Roth‘s writing in the 20s, London 2006: Maney Publishers.

- Klimbacher, Wolfgang: Von den 'glänzenden Zeiten Europas' zur 'maschinellen Hinrichtungsart' in 'Barbaropa'. Das Trauma des Ersten Weltkriegs bei Trakl, Kafka und Ehrenstein, in: Zeitschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Linguistik 28/109, 1998, pp. 100-118.

- Mayer, Mathias: Der Erste Weltkrieg und die literarische Ethik. Historische und systematische Perspektiven, Munich 2010: Fink.

- Nehring, Wolfgang: Die Suche nach dem höheren Selbst. Zu Hofmannsthals Kriegsprosa, in: Ernst, Petra / Haring, Sabine A. / Suppanz, Werner (eds.): Aggression und Katharsis. Der Erste Weltkrieg im Diskurs der Moderne, Vienna 2004: Passagen-Verlag, pp. 77-96.

- Rachewiltz, Siegfried W. de / Engl, Christine (eds.): Die düstern Adler. Der Erste Weltkrieg in Kunst, Literatur und Alltag. Wahn und Wirklichkeit, Meran 2005: Landesmuseum für Kultur- und Landesgeschichte Schloss Tirol.

- Rieger, Markus: Zauber der Montur. Zum Symbolgehalt der Uniform in der österreichischen Literatur der Zwischenkriegszeit, Vienna 2009: Braumüller.

- Sauermann, Eberhard: Literarische Kriegsfürsorge. Österreichische Dichter und Publizisten im Ersten Weltkrieg, Vienna 2000: Böhlau.

- Sauermann, Eberhard: Österreichische Kriegsdichtung im Ersten Weltkrieg. Poetische Mobilmachung in Tirol, in: Mazohl-Wallnig, Brigitte / Kuprian, Hermann; Barth-Scalmani, Gunda et al. (eds.): Ein Krieg - zwei Schützengräben. Österreich-Italien und der Erste Weltkrieg in den Dolomiten 1915-1918, Bozen 2005: Verlagsanstalt Athesia, pp. 181-199.

- Schmidt-Dengler, Wendelin: Ohne Nostalgie. Zur österreichischen Literatur der Zwischenkriegszeit, Vienna 2002: Böhlau.

- Schneider, Thomas F.: Die Autoren und Bücher der deutschsprachigen Literatur zum Ersten Weltkrieg 1914-1939. Ein bio-bibliographisches Handbuch, Göttingen 2008: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Schumann, Andreas: 'Der Künstler an die Krieger'. Zur Kriegsliteratur kanonisierter Autoren, in: Mommsen, Wolfgang J. (ed.): Kultur und Krieg. Die Rolle der Intellektuellen, Künstler und Schriftsteller im Ersten Weltkrieg, Munich 1996: Oldenbourg, pp. 221-233.

- Schumann, Andreas: 'Macht mir aber viel Freude'. Hugo von Hofmannsthals Publizistik während des Ersten Weltkrieges, in: Schneider, Uwe / Schumann, Andreas (eds.): Krieg der Geister. Erster Weltkrieg und literarische Moderne, Würzburg 2000: Königshausen und Neumann, pp. 137-151.

- Stephens, Anthony: Das 'gleiche tägliche Entsetzen' und die Stimme des Dichters. Rilke 1914-1918, in: Schneider, Uwe / Schumann, Andreas (eds.): 'Krieg der Geister'. Erster Weltkrieg und literarische Moderne, Würzburg 2000: Königshausen und Neumann, pp. 154-169.

- Szczepaniak, Monika: Militärische Männlichkeiten in Deutschland und Österreich im Umfeld des Grossen Krieges. Konstruktionen und Dekonstruktionen, Würzburg 2011: Königshausen und Neumann.

- Waldner, Hansjörg: 'Deutschland blickt auf uns Tiroler'. Südtirol-Romane zwischen 1918 und 1945, Vienna 1990: Picus.