Early Political Activism↑

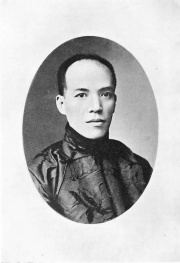

Liang Qichao (1873-1929) rose to prominence in the waning years of the Qing Empire (1644-1911). He was one of the leading voices of the 1898 Hundred Days’ Reforms (Wuxu Bianfa) that aimed to reinvigorate China by transforming the struggling empire into a constitutional monarchy. When court conservatives thwarted these efforts, Liang had to flee to Japan, where he stayed until the overthrow of the Qing Empire and the establishment of the Republic of China in 1912. While in exile, Liang became a vocal critic of Chinese traditional thought and a staunch proponent of Western Social Darwinist notions of human progress. His prolific journalistic work was widely circulated in China and turned Liang into the foremost Chinese intellectual leader of the first two decades of the 20th century.

China’s Entry into the War↑

As a keen observer of world politics, Liang realized in the early 1910s that tensions between the European great powers were growing. He recommended that China make use of this situation to strive for national equality and international recognition,[1] yet despite briefly serving as China’s minister of justice (September 1913-February 1914), his influence on Republican politics initially remained low. Shortly after the outbreak of war in Europe, Liang tried to influence both Chinese public opinion and the government by journalistic means. In late 1914, he published a monograph entitled Historical Discussion of the War in Europe in which he predicted Germany’s victory on the grounds of the supposedly outstanding qualities of its people.[2] In early 1915, following Japan’s recent occupation of the German concession of Jiaozhou (Kiautschou) Bay and now considerably less convinced of a German victory, Liang began to call for a Chinese war contribution, hoping to thus awaken Chinese national consciousness and secure a seat at the table of a future post-war peace conference.[3]

At the same time, Liang Qichao privately urged high-ranking government officials to lead China into the war. Throughout the summer and autumn of 1914, Liang repeatedly met with President Yuan Shikai (1859-1916), in office from 1912 to 1916, and argued that China could only hope to regain Jiaozhou Bay from Japan if it joined the war. Liang also stayed in close contact with Duan Qirui (1865-1936), four-time prime minister and three-time army minister between March 1912 and October 1918. Even though Duan agreed with Liang’s assessment of the situation, China remained officially neutral until 1917. On 8 February 1917, in reaction to the recent United States decision to break off diplomatic relations with Germany, Liang was called to Beijing by President Li Yuanhong (1864-1928), in office from 1916 to 1917, to advise the Chinese government on its further course of action. As a result, China submitted a note of protest to Germany, demanding the immediate cessation of unrestricted submarine warfare.[4]

On 14 March 1917, China officially severed its diplomatic ties with Germany, but a Chinese declaration of war only followed on 18 August 1917. In the meantime, Liang continued to put pressure on the government by eloquently promoting the idea that China’s entry into the war would result in an elevation of its international status and prestige and, ultimately, the permanent recovery of its lost sovereignty and territorial integrity.[5]

Voyage to Europe and Paris Peace Conference↑

After the Chinese declaration of war, Liang’s political clout waned amidst domestic turbulence. In December 1918, he therefore accepted an invitation by the Chinese government to travel to Europe to participate in the Paris Peace Conference in a nonofficial function. Even though Liang insisted that his only aim was to influence the public opinion of other countries and to inform his compatriots of the conference’s proceedings,[6] he did, in fact, also advise the Chinese envoys to the United States, V. K. Wellington Koo (1888-1985); the United Kingdom, Alfred Sao-ke Sze (1877-1958); and France, Hu Weide, (1863-1933), who participated in the conference, and he met with President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) in March 1919.

While in Europe, Liang visited various countries to gain first-hand insight into the effects of the war. He was initially hopeful that the horrors of the world war and the Entente’s victory would lead humanity towards justice, democracy, world peace and global cooperation,[7] but the victorious powers’ ruthless behavior at the peace conference convinced Liang that the Social Darwinist dictum of “might is right” continued to hold sway in international politics.[8] Accordingly, Liang reversed his hitherto negative opinion of Asian traditional thinking and began to argue that it was a special responsibility of the Chinese people to share their spiritual tradition with a world that was in dire need of a moral renewal.[9]

Travel Impressions from Europe and Chinese Intellectual Debates in the 1920s↑

During his stay in Europe, Liang developed the idea that humanity’s salvation was dependent on the revival of Asian spiritual traditions, thus mirroring the deliberations of many other Asian observers at the time (e.g. the Japanese Buddhist Watanabe Kaigyoku (1872-1933) or the Indian writer Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941)). Upon his return to China in March 1920, he began to promote his new views by publishing his lengthy report, Travel Impressions from Europe, in Beijing and Shanghai newspapers. Liang recounted his time in Europe and argued that the horrors of the First World War were the result of the fundamental flaws of the Western modernization model. In the West, too firm a belief in the omnipotence of science had led to a neglect of questions of morality, and an overemphasis on nationalistic ideals had inhibited the development of individualism and cosmopolitanism. By contrast, emphasized Liang, Asia’s spiritual traditions were especially suited to remedy these flaws.[10]

Liang’s limited criticism of science, his appreciation of Asia’s spiritual traditions and his skepticism of nationalism put him at insurmountable odds with the most powerful socio-political trends of his time, the New Culture Movement (Xin Wenhua Yundong) of the 1910s and the nationalistic May Fourth Movement (Wu-Si Yundong). Until his death in 1929, Liang would continue to promote the ideas in Travel Impressions from Europe, but he would never regain the intellectual influence he had enjoyed in the first two decades of the 20th century.

Clemens Büttner, Goethe Universität Frankfurt am Main

Section Editor: Urs Matthias Zachmann

Notes

- ↑ Liang, Qichao: Zhongguo waijiao fangzhen siyi [My Opinion on China’s Foreign Policy Guidelines], originally published in Guofengbao in October 1910 (see Lin Zhijun (ed.): Yinbingshi heji [Combined Collection of Writings from the Ice-Drinker’s Chamber], wenji 8, juan 23, Shanghai 1936, pp. 79-106).

- ↑ Liang, Qichao: Ouzhou zhanyi shilun [Historical Discussion of the War in Europe], Shanghai 1914 (see Lin, Yinbingshi heji 1936, zhuanji 8, juan 30).

- ↑ Liang, Qichao: Ouzhan lice [Preliminary Assessment of the European War], originally published in Da Zhonghua from January to March 1915 (see Lin, Yinbingshi heji 1936, wenji 12, juan 33, pp. 11-26).

- ↑ Liang-Zhang zhi Zhong-De guoji qiantuguan [Liang [Qichao] and Zhang [Shizhao]’s Views on the Future of Sino-German relations], in: Shenbao, 13 February 1917, p. 3.

- ↑ Liang, Qichao: Waijiao fangzhen zhiyan [Sincere Words on [China’s] Diplomatic Guidelines], originally published in Minguo ribao in March 1917 (see Lin, Yinbingshi heji 1936, wenji 12, juan 35, pp. 4-13).

- ↑ Liang Rengong yu woguo jianghe wenti [Liang Rengong [i.e. Liang Qichao] and the Question of China’s [Role During] the Peace Talks], in: Chenbao, 6 April 1919, p. 2.

- ↑ Liang, Qichao: Guoji tongmeng yu Zhongguo [An International Alliance and China], originally published in Dongfang zazhi in February 1919 (see Tang Zhijun / Tang Renze (eds.): Liang Qichao quanji [Complete Works of Liang Qichao], volume 9, Beijing 2018, pp. 831-834).

- ↑ Liang, Chi-chao (i.e. Liang Qichao): Causes of China’s Defeat at the Peace Conference, in: Millard’s Review 9/7 (1919), pp. 262-268; Liang, Qichao: Liang Rengong di Hu hou zhi tanhua [Talk by Liang Rengong [i.e. Qichao] after arriving in Shanghai], originally published in Shenbao in March 1920 (see Tang, Liang Qichao quanji 2018, volume 15, p. 210).

- ↑ Liang, Qichao: Gaizao fakanci [Foreword to the periodical Gaizao], originally published in Gaizao 3/1 (1920), pp. 5-7 (see Tang, Liang Qichao quanji 2018, volume 10, pp. 195-198).

- ↑ Liang, Qichao: Ouyou xinying lu [Travel Impressions from Europe], originally published in Chenbao (Beijing) and Shishi xinbao (Shanghai) between March and July 1920 (see Lin, Yinbingshie heji 1936, zhuanji 5, juan 23, for an abridged version).

Selected Bibliography

- Gao, Like: Wannian Liang Qichao de wenhua zijue – 'ouyou xinying lu' de xiandaixing fansi (Liang Qichao’s cultural consciousness in his later years – rethinking modernity in 'Travel Impressions from Europe'), in: Xuexi yu tansuo (Study & Exploration) 2, 2019, pp. 31-38.

- Lee, Soonyi: In revolt against positivism, the discovery of culture. The Liang Qichao Group’s cultural conservatism in China after the First World War, in: Twentieth-Century China 44/3, 2019, pp. 288-304.

- Levenson, Joseph R.: Liang Ch’i-ch’ao and the mind of modern China, Berkeley; Los Angeles 1967: University of California Press.

- Tang, Xiaobing: Global space and the nationalist discourse of modernity. The historical thinking of Liang Qichao, Stanford 1996: Stanford University Press.

- Zheng, Shiqu: Ouzhan hou Liang Qichao de wenhua zijue (Liang Qichao’s cultural awareness after World War I), in: Beijing Shifan Daxue xuebao (shehui kexueban) 3, 2006, pp. 49-59.