The Hairy Ones↑

The literal translation of Le Poilu is “the hairy one” and it is used as an informal collective term to describe the men who made up the French infantry soldiers during the First World War. However, it is also representative of a national and political identity which these men embraced as both a reaction to the war and their own conception of republican France.

At its most basic level, the term Poilu refers to the appearance of the regular French infantryman. It became custom for French soldiers to grow their hair and beards long at the outbreak of the war as an expression of their masculinity. The term first rose to wider prominence in the 1834 story by Honoré de Balzac (1799-1850), Le Médecin de Campagne. In the novel, a highly dangerous mission requires the participation of a group of French soldiers with only forty men being deemed hairy enough to undertake it.

Hair as a signifier for masculinity and strength has its roots in the biblical tale of Samson, but with Le Poilu it found an additional resonance in regards to the way the First World War was waged and the reasons behind it. The nature of trench warfare, with soldiers rapidly coming to live a semi-subterranean life within the mud and dirt of La Patrie, convinced French soldiers that it was not possible to fight such a conflict without embracing this mud and dirt. It was not possible to save the country they loved without immersing themselves in its very ground, by becoming dirty, and hairy, and embracing a sense of base masculinity.

This position often put them at odds with British soldiers in particular, as the British soldierly identity of the “Tommy” was heavily predicated on the importance of a clean appearance in maintaining discipline and fostering a military spirit. As a result, to British eyes, the French often appeared unkempt and ill-disciplined.

Additionally, this manifestation of the French warrior spirit also links back to the French rural tradition of men working the fields and the soil of La Patrie in a manner that speaks of both an honest masculinity but also a deep love and appreciation of France as the mother and sustainer of the French people. Beyond this, it also gave an outlet for the expression of the republican identity these men created for themselves.

Les Poilus and Republican Identity↑

Since the earliest days of the French Revolution, Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s (1712-1778) declaration; “Every soldier a citizen, every citizen a soldier” has described the binary relationship between the people of France and their role in its preservation and defense. However, this relationship is also one of community, participation and debate. The soldiers of the First World War did not view themselves as passive pieces in this situation, devoid of opinion or agency. Les Poilus were fighting for France and they had very particular beliefs about what “France” represented and how best it would be defended.

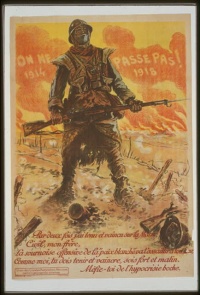

These positions became clear during the French mutinies of 1917 during and after the failed offensive at the Chemin des Dames. When it became clear that General Robert Nivelle (1856-1924), then French commander-in-chief, was not going to secure a decisive victory and that French casualties were rapidly growing, reports began to surface of French soldiers baa-ing like sheep on their way to slaughter as they passed up the lines towards the battle. This movement spread in a wider display of political dissent as soldiers in the area refused to attack. Their message to the French military command was that they would continue to defend the land of their country but they were not willing to cast away their lives in a pointless offensive.

On the surface, this might appear a simple act of non-political mutiny. However, Les Poilus viewed themselves to be the descendants of those republican soldiers who had built modern France; they believed that both the country and its citizen-soldiers deserved better than death in attempting the unachievable. It was only by addressing the political motivations of these mutinies that General Philippe Pétain (1856-1951), Nivelle’s replacement, was able to rebuild the morale and fighting effectiveness of the French army. These measures allowed the French infantry to play a crucial role in the eventual victory of 1918, not simply through their own strength of arms, but through achieving it in a manner that was compatible with their own identity and belief in what the war was for and how it must be fought.

Post-war↑

Whilst the eventual victory had been sufficiently Poilu-esque, and many of those who had served in the French army continued to take pride in their wartime identity, many soldiers began to look outwards in their desire to maintain the peace they had won. The rise of internationalism saw many former Poilus attempt to foster cooperation between the various combatants during the inter-war years. The eventual failure of this attempt followed by the defeat of the French army in 1940 meant that the Poilu identity did not reemerge as a cohesive movement during the Second World War.

Chris Kempshall, University of Sussex

Section Editor: Alexandre Lafon

Selected Bibliography

- Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane / Becker, Annette: 1914-1918. Understanding the Great War, London 2002: Profile.

- Greenhalgh, Elizabeth: The French army and the First World War, Cambridge 2014: Cambridge University Press.

- Loez, André: 14-18, les refus de la guerre. Une histoire des mutins, Paris 2010: Gallimard.

- Smith, Leonard V. / Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane / Becker, Annette (eds.): France and the Great War, 1914-1918, Cambridge; New York 2003: Cambridge University Press.