Career Prior to Becoming U.S. Secretary of State↑

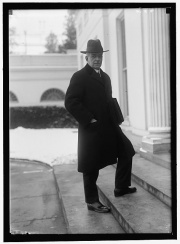

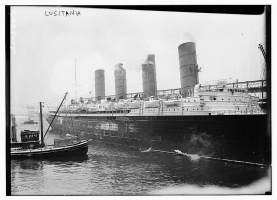

Robert Lansing (1864-1928), a career lawyer, served as President Woodrow Wilson’s (1856-1924) Secretary of State after his predecessor, William Jennings Bryan (1860-1925), resigned in protest over Wilson’s response to the 1915 sinking of the Lusitania. Lansing’s pre-war success in representing U.S. interests in international tribunals earned him the position of State Department Counselor in 1914, and together with Colonel Edward M. House (1858-1938), he helped shape the president’s initial policy responses to the outbreak of war in Europe. Unlike the near pacifist Bryan, or House, who was more European than American in his diplomatic thinking, Lansing’s early stance on the war reflected his conservative values and commitment to the rule of law and interests of American business. As a result, Lansing was at first a staunch proponent of the U.S. remaining aloof from the European conflict.

As the historian Ernest May (1928-2009) notes, however, Lansing’s neutrality quickly took on a pro-Entente cast, evolving into what the British Foreign Minister Edward Grey (1862-1933) described as “benevolent neutrality.”[1] Lansing’s influence on U.S. foreign policy was greatest at the start of the war while he was still Counselor. Wilson’s belief that the war would be short and Bryan’s disinterest in the technical issues of neutrality allowed Lansing to formulate policies that favored the Entente, specifically the British, such as only allowing merchant ships armed with “defensive” weapons to leave U.S. ports (ships deemed to carry “offensive” weapons were impounded). Lansing was also instrumental in reversing Bryan’s earlier ban on loans to the combatant nations, affirming the right of U.S. manufacturers to sell arms to any country capable of importing them (which the Central Powers could not, because of the British naval blockade), and muting official U.S. protest of Britain’s use of mines in its naval blockade of Germany.

Career after Becoming U.S. Secretary of State↑

After Lansing succeeded Bryan, he exerted an uneven influence on U.S. foreign policy until the war’s end. Lansing’s notable accomplishments included securing the U.S. Virgin Islands from Denmark in 1916, and the Lansing-Ishii Agreement of 1917 with Japan, which publically committed both countries to maintain the Open Door Policy in China while at the same time recognizing Japan’s “special interests” in the country. He is also credited with founding the State Department’s Bureau of Secret Intelligence, the predecessor of the U.S. Diplomatic Security Service. Lansing, however, more often found himself at odds with Wilson, who increasingly turned to House for advice and to represent U.S. interests in discussions with Entente leaders.

The distance between Lansing and Wilson’s diplomatic approach prior to the U.S. declaration of war stemmed largely from each man’s commitment to the Entente. Lansing initially subscribed to benevolent neutrality and vehemently objected to the British blockades. He thought they represented a danger to the freedom of the seas and rights of neutral nations, but his concerns about the British disappeared as a result of Germany’s submarine campaign. By 1916, he favored the U.S. joining the Entente. This contrasted with Wilson’s desire to maintain the country’s neutrality, even if doing so meant antagonizing the British. The gap between Lansing and Wilson grew during repeated crises in Anglo-American relations over the British use of blockades, blacklisting of foreign companies, and other forms of economic warfare. Increasingly, Lansing feared that Wilson’s “resentment at the British invasions of our rights...” could result in “drastic measures against Great Britain... [for which] he will never be forgiven...”[2]

By the war’s end, Lansing’s doubts about the efficacy of Wilson’s Fourteen Points and his strenuous objections to the President’s intent to attend the peace negotiations caused an outright rupture in their working relationship. Lansing travelled to Paris in 1918 as the nominal head of the U.S. delegation to the Peace Conference, a position Wilson gave very reluctantly to the man he considered to have, “no imagination, no constructive ability, and but little real ability of any kind.”[3] Lansing, for his part, was profoundly disillusioned with the president and what he perceived as a dangerously naïve idealism about issues such as “national self-determination,” an idea he described as “loaded with dynamite.” Wilson’s participation in “secret diplomacy” and his admission of Japanese claims to possession of Germany’s treaty rights in China also troubled him.[4] As a result, Lansing played only a minor role in the subsequent negotiations. In all the important discussions, Wilson either participated personally or authorized House to act on his behalf. To Lansing fell the responsibility of daily press briefings, a task he despised, and the minor role of negotiating the Shandong (Shantung) Settlement.

Unsurprisingly, Lansing was critical of the final peace treaty, describing it as “immeasurably harsh and humiliating,” a document filled with provisions that stood little chance of succeeding and which demonstrated the extent to which European diplomats had overwhelmed the president.[5] During the remainder of his time in office, Lansing faced the impossible task of defending a treaty of which he did not approve. When called to testify in front of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Lansing chose not to make a strong case for the League of Nations and declined to answer questions about the Covenant’s origins. Although Wilson felt greatly betrayed, Lansing, in fact, worked diligently on the treaty’s behalf. Convinced that it would never pass the Senate without at least minor changes, he urged Wilson to accept some Republican revisions. Ultimately, however, Wilson and the rest of the cabinet rejected Lansing’s plea for modest concessions, resulting in the Senate’s rejection of the Paris Peace Treaty on 9 November 1919.

The final split between the two men occurred in February 1920 when Wilson, convinced that Lansing was acting with too much independence, demanded and received the latter’s resignation. After leaving the State Department Lansing remained in the Washington, D.C. area practicing and publishing in the field of international law until shortly before his death in 1928.

Nicholas J. Steneck, Wesleyan College

Section Editor: Lon Strauss

Notes

- ↑ May, Ernest R.: The World War and American Isolation, 1914-1917, Cambridge, MA 1959, p. 42.

- ↑ Lansing Diary Entry dated September 1916. Quoted in: May, The World War 1959, op. cit., 332.

- ↑ MacMillan, Margaret: Paris 1919. Six Months that Changed the World, New York 2001, p. 5.

- ↑ Sharp, Alan: Consequences of Peace. The Versailles Settlement - Aftermath and Legacy, New York 2011, p. 102; Lansing, Robert: The Peace Negotiations. A Personal Narrative, New York 1921, pp. 8-9, 203.

- ↑ MacMillan, Paris 2001, p. 467.

Selected Bibliography

- Cooper, John Milton, Jr.: Woodrow Wilson. A biography, New York 2009: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Cooper, John Milton, Jr.: Breaking the heart of the world. Woodrow Wilson and the fight for the League of Nations, Cambridge; New York 2001: Cambridge University Press.

- MacMillan, Margaret: Paris 1919. Six months that changed the world, New York 2002: Random House.

- May, Ernest R.: The World War and American isolation, 1914-1917, Cambridge 1959: Harvard University Press.

- Sharp, Alan: Consequences of peace. The Versailles settlement. Aftermath and legacy, 1919-2010, London 2010: Haus.

- Smith, Daniel Malloy: Robert Lansing and American neutrality, 1914-1917, New York 1972: Da Capo Press.