Introduction↑

Before the outbreak of the First World War, economic depression had shaken the Canadian economy, leading to rampant unemployment. As a result, on the eve of the First World War, Canadian labour – i.e., workers organised into unions to achieve common goals – was mostly organised on a small scale, if at all. Radicalization of workers was also limited, with few individuals organizing in workplaces and few protests held against employers. Under such conditions, strikes occurred, but rarely succeeded in achieving workers’ goals. These organizational weaknesses opened Canadian labour to outside influence, particularly from American-based international unions, which led to a division between craft and industrial unions.

Over the course of the war, union membership expanded to unprecedented levels. Radicalization of labour increased, and the power of more conservative unions waned in the later war years. The government curtailed civil liberties and used conscription in an effort to limit the influence of radical labour leaders, but had little success. A general strike that began in Winnipeg, Manitoba, on 15 May 1919 resulted in street violence, and was used by the federal government as an excuse to limit the power of organised labour in the immediate post-war years. Thus, while labour’s power increased during the war, government suppression prevented major changes from being consolidated, and so the gains made during the war years were effectively lost for decades to come.

Labour Unions in Canada before the War↑

Before the war, unions were present throughout the country, but exercised only limited power. American-based international unions dominated and heavily influenced how Canadian labour was organised in the pre-war years.[1] On the eve of the war, Canada was suffering an economic depression, resulting in high unemployment. Desmond Morton argues that the economic downturn was caused by overproduction, dismissing the common explanation of insufficient manufacturing ability.[2] There was no national unity among labour unions, nor among the working class more generally. The Trades and Labour Congress (TLC) was the strongest labour group in Canada in the pre-war period, but it was not a national organization. It claimed to speak for labour in Canada, when in fact few workers were organised into unions and not represented by the TLC. Despite this, the TLC was unofficially recognized by the federal government as representing labour in Canada.[3] Based primarily in the more industrialised Eastern part of the country, the TLC’s narrow definition of trade unionism, which precluded many workers from joining, prevented the development of working-class solidarity on a nation-wide basis.[4] It focused on skilled trades; hence the name craft unions. The TLC’s affiliation with the American Federation of Labor (AFL) highlights the influence of American business unionism in pre-war Canada: American money financed the expansion of TLC unions.[5] Labour militancy was divided along regional lines in and shied away from extremism, largely due to the economic conditions and the conservative nature of trade unionism.[6] Radicalization was thus also limited, but the global war sent tremors throughout Canadian labour.

Labour’s Response to the Outbreak of War↑

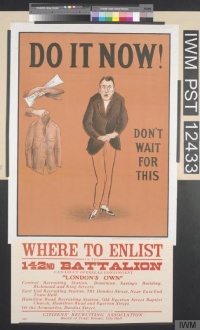

Much like the rest of the population, Canadian labour largely supported the war. Many men from the traditional ranks of organised skilled labour rushed to the colours. However, some sectors of labour were against war, and called for general strikes to cripple the country and prevent its entry into the conflict. These radical groups were in the minority, and no substantial protests developed. Attesting to labour’s weakness and in contrast to most other belligerent countries, the federal government under Prime Minister Robert Borden (1854-1937) did not seek the opinion of labour leaders. This decision prompted anger and distrust towards the government among the labour ranks; there was, however, very little they could do to strike at traditional power bases. This would change during the course of the war.

The Labour Revolt↑

There is no consensus as to when the Canadian labour revolt began. The ongoing economic depression initially hampered any strong, organized opposition to the war or the Borden government. In 1915, however, increased industrial output for the war effort helped to end the depression. The need to increase production of armaments such as shells led to growth in the metalworking industry, which needed tens of thousands of new workers to keep up with munitions orders.[7] Increased employment, especially of unskilled workers and women, triggered fears in craft unions of labour dilution: If greater numbers of non-skilled workers entered the workforce, the craft unions might lose their influence in labour unions. Non-skilled women entering the workforce were a large concern, as they threatened the traditionally male-dominated industrial occupations that allowed unions to maintain their power within Canadian labour. This fear turned out to be unfounded, as Douglas McCalla argues, since women made up only a small percentage of the total munitions industry workers.[8]

The exact impact of the war on women in the workforce is still debated. A popular myth, challenged by Joan Sangster, is that women rushed to munitions plants in large numbers to fill jobs left by men who had gone to war. Estimates of women workers in munitions for the entire war range from 10,000 to 35,000. In 1917, munitions workers made up less than 20 percent of total women workers.[9] Instead, Sangster contends, women largely replaced men in clerical work, a trend that had begun before the war. This started a “feminization” of clerical work that continued into the post-war years, something that did not occur in industrial occupations.[10] This position is supported by Kori Street, who demonstrates that over 50 percent of employed women in 1917 worked as clerks.[11] Traditional union power bases were very much reinforced by the war.

The growing power of workers, who were crucial to the war effort, allowed the unions to take bolder anti-war stances, as well as to seek a better position vis-à-vis their employers. While by the war’s end, almost 37 percent of the Canadian Expeditionary Force had listed their occupations as “industrial”, workers at home started to strike, partly in protest of the war.[12] Workers also struck for higher wages, job security, and safer working conditions. Some historians claim the labour revolt began in 1916, while others place it in late 1917 with the election of the Union government, the introduction of conscription, and the orders in council that curbed the civil liberties of labour and trade unions.

Union membership was limited at the beginning of the war, but increased with each year of conflict. At the end of 1915, membership in Canada was at 140,000, and by 1916, had marginally increased to 160,000. The later years of the war saw a larger increase in membership: By the end of 1917, the total was approximately 205,000, and in 1918 250,000. By 1919, 378,000 workers had unionized.[13] These numbers were not maintained in the post-war years, however. By 1922, there were 100,000 fewer union members than in 1919.[14]

There was a large amount of strikes during the war and in its immediate aftermath. In 1917, 218 strikes were recorded, in which a total of more than 50,000 workers had participated. By 1919, the number of strikes rose to 427 with 150,000 workers, and by 1920, the number had reached 457. It has been estimated 350,000 wage-earners struck from 1917-1920.[15] Several regions offer insight into the number labour days lost: The Maritimes lost a large amount of production for a relatively small region. The number of strikes more than doubled, from eleven in 1917 to twenty-seven in 1918, and the number of days occupied by wartime strikes soared from 12,549 to 84,121.[16] In southern Ontario, the number of days lost in strikes grew from 25,000 in 1915, to 77,000 in 1916, to over 120,000 in 1918.[17]

Conflict was not constrained to workers and employers, but also occurred between labour groups. The TLC faced opposition from the One Big Union (OBU), which advocated that all sectors of labour, skilled and unskilled, be represented by one organization. Ian McKay identifies the challenge of the OBU to traditional union power bases as the largest home-grown left-wing organization during the First World War.[18] The OBU started in Western Canada when its members split from the TLC in March 1919 at conference in Calgary, Alberta. This splinter group openly identified with the Russian Revolution and socialism, and favoured the use of general strikes in order to have their demands met. The TLC had opposed all of these elements. Given its commitment to socialist principles, the OBU also favoured including as many people as possible. This included women, workers from other countries, and ethnic minorities.[19] The founding of the OBU contributed to the events that led to the Winnipeg General strike in spring 1919.

The degree of intensity in the labour revolt varied by region. Many Ontario workers benefitted from the increase in war production, and were therefore less radical. In the Prairie provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta, the labour revolt was more radical and socialist-inflected. The influence of regionalism, like the beginning of the labour revolt, remains an area of controversy among historians. Gregory S. Kealey argues that “the revolt was national in character and that its seeds were not rooted in any unique regional fermentation. The ‘radical’ West and the conservative East have become sorry shibboleths of Canadian historiography. The foundations of our understanding of 1919 must be built on national and international conjunctures.”[20] Despite the regional bias of the historiography identified by Kealey, there were changes that had a national effect on labour.

The Bolshevik revolution in October 1917 and the Russian exit from the war in March 1918 led the Borden government to introduce more draconian laws against organized labour. Ethnic and racial divisions in Canada also played a part in the creation of these laws. The earlier Order-in-Council P.C. 1743, issued on 11 July 1918, outlawed strikes and lockouts, while assuring the right of workers to organize.[21] Order-in-Council P.C. 2384, issued on 25 September 1918, declared several political groups and unions illegal, including the International Workers of the World (IWW), the Russian Social Democratic Party, the Russian Revolutionary Group, the Russian Social Revolutionists, the Russian Workers Union, the Ukrainian Revolutionary Group, the Ukrainian Social Democratic Party, the Social Democratic Party, the Social Labour Party, the Group of Social Democrats of Bolsheviki, the Group of Social Democrats of Anarchists, the Workers International Industrial Union, the Chinese Nationalist League, and the Chinese Labour Association.[22] There was an additional ban on “any association, organization, society or corporation, one of those purposes or professed purposes is to bring about any government, political, social, industrial, or economic change within Canada”.[23] Any type of literature espousing the views of these banned publications was subject to government seizure without a warrant. Finnish-, Ukrainian-, and Russian-language newspapers and publications were banned for their perceived connection to the communist uprisings in each of these countries, and the state expanded its power of censorship, granted in the early stages of the war by the War Measures Act. Meetings conducted in these languages, other than religious services, were also banned. Such measures were mostly able to keep radical behaviour in check during war, but this would not be the case after the armistice.

Revolt against Conscription and Division in Canada↑

Anti-conscription protests and resistance were part of the larger labour revolt against the war from mid-1917 onward. Though the TLC generally supported the war, it took a hardline anti-conscription stance, and most labour groups followed. As the war progressed, conscription became a necessity after the high casualties Canada suffered at Vimy Ridge, Hill 70, and Passchendaele. In May 1917, after returning from France and seeing the personal toll the war was taking on Canadian soldiers, whom he had visited in hospital, Prime Minister Borden reversed his promise not to enact conscription. Borden had first recommended a voluntary information-gathering scheme, where men submitted information about themselves to allow the government to gauge the human resources available for the Canadian war effort. Labour was divided on its support for this measure. Many in its ranks feared it was the first step to conscription. The TLC leadership accepted the scheme shortly after its creation in autumn 1916, assured that conscription would not occur, and recommended compliance to their members. Gregory S. Kealey notes that “this apparent surrender of the labour movement’s purely voluntarist stance led to renewed opposition to the TLC leaders, especially in Quebec and the west, but also in Ontario.”[24] The measure, of course, did lead to conscription: The Military Service Act of 1917 (MSA) was put to a pseudo-referendum in the 1917 federal election. The Unionist party, made up of Conservatives and pro-conscription Liberals, represented conscription, while the opposition Liberals were against it. The TLC ultimately voted not to oppose the implementation of conscription.[25] This did not prevent many labour representatives from running in the election on anti-conscription platforms, and there were many demands to conscript wealth along with young men. Both the political elite and labour leaders called for some form of conscription of wealth. Although income tax was introduced in 1916 and 1917, candidates from all political parties argued this did not go far enough.[26] None of the labour candidates were elected, but the issue of conscription had brought labour into federal politics for good.

Some historians have connected to the popular resistance to conscription to the overall labour revolt. There is some truth to this, but other factors more strongly motivated the protestors. Ian McKay links conscription opposition to labour by stating that the 1918 Easter anti-conscription riots in Quebec City took place in the working-class suburbs and was therefore part of the political left’s protest efforts.[27] This deviates from the more traditional view that the riots resulted from French-Canadian dissatisfaction with the war effort and the enforcing of conscription in Quebec.[28] This particular outbreak of protests followed the harassment of men who had received exemptions from conscription. Violence broke out when the crowd threw bottles and snowballs at the troops, mostly conscripts themselves, who had been sent to restore order on 1 April 1918. Other accounts allege that shots were fired from the crowd or from other concealed positions. The troops were ordered to open fire on the crowd. After the guns fell silent, four rioters lay dead and many more had been wounded.[29] The violence of the battlefields, thought to be far away, had reached Canada.

Conscription further exasperated the divide between urban and rural Canadians, which had been growing prior to the outbreak of war. In the early years of the 20th century, many people had moved from rural farms and communities into larger cities seeking better wages. The outbreak of war caused further rifts between these two sets of the Canadian population. While farmers were initially praised by the government and elites as contributing to the war effort, as inflation rose from 1916, some in the cities looked for the cause. They blamed farmers, who they thought were growing rich off urban suffering.

Worker shortages struck rural farmers first, as higher wages at munitions factories and war service drew more people to the cities. Farmers, particularly in Ontario and the Prairie provinces, became involved in the labour revolt because of conscription. The issue of farm labour and conscription is not often presented as being a concern in Quebec; however, Jatinder Mann argues that concerns over maintaining farm labour were a factor in French-Canadian opposition to conscription, in addition to not having an emotional connection to the British Empire.[30] Farmers had initially been promised exemption from conscription, and when this protection was removed, they organised against conscription. They took their protest to Ottawa, but to no avail: The conscripting of farmers continued until the measure was ended in early 1919. Conscription and the perceived dismissal of their concerns of depopulation by both the provincial and federal government prompted farmers to stand for and win the Ontario provincial election in October 1919. Drawing on the strength of this victory and the discontent in the West, the Progressive Party of Canada became the Official Opposition in the federal parliament after the 1921 election. That election also saw numerous labour politicians elected to office: Joseph Shaw (1883-1944) and William Irvine (1885-1962) won as Labour candidates in Calgary, J. S. Woodsworth (1874-1942) in Winnipeg.[31] Woodsworth was the first leader of the Co-operative Commonwealth Foundation, a political party that brought together labour, farmer’s groups, and socialists in the 1930s. It became the New Democratic Party in 1961, and continues to represent the labour position on provincial and federal levels. Conscription had brought different sections of labour into Canadian politics, forever changing the political landscape.

The 1919 Winnipeg General Strike↑

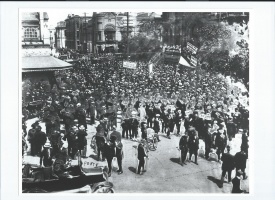

The most radical elements of the labour revolt did not begin until after the war had ended. Growing discontent with government repression and perceived greed on the part of employers led to one of the most violent and divisive labour strikes in Canadian history. The 1919 Winnipeg General Strike was the culmination of years of war, anger, repression, and loss. It began in earnest when metal trades and building workers walked off the job in early May, demanding wage increases and the right to collective bargaining.[32] It expanded into a general strike two weeks later when the TLC voted to support it. On 15 May 1919, between 25,000 and 30,000 workers left their workplaces at eleven o’clock in the morning.[33] Sympathy strikes broke out in numerous Canadian cities, but none reached the fervour of Winnipeg. The city was essentially shut down. Mail stopped running, telephone service was suspended, and garbage collection ceased. Police officers were laid off for their pro-strike inclinations and special constables hired to replace them. In addition, large numbers of returning Canadian soldiers were involved in the strike, with some on the side of the protestors, others entering the new police force.[34] The local and provincial governments did little to try to end the strike, but feared that the Bolsheviks had wormed their way into the organizations. As the strike dragged on, the federal government intervened and a number of strike leaders were arrested in the early morning of 19 June. That led to a new round of violence, which broke out on 21 June when strikers defied the ban on parades and gathered at the intersection of Portage and Main in downtown Winnipeg. Royal Northwest Mounted Police (RNMP) officers on horseback used batons and gunfire to disperse the crowd. The special constables followed, beating protestors with their batons. Rioting broke out, resulting in two deaths, numerous injuries, and dozens of arrests.[35] This day would come to be called “Bloody Saturday”, its iconic image that of a lone burning streetcar from that day. Between the arrests of the strike leaders and the violence, support was waning, and by 25 June, the strike was called off.[36] Though it did not achieve labour leaders’ goals, the Winnipeg General Strike remains in an important symbol of labour rights in Canada.

The Legacy of the War for Labour↑

The crucible of war changed Canada in many ways, but labour remained outside the structures of power after the fighting had ended. Unions opened their ranks to new members because of the war. Craig Heron concludes that more women and ethnic minorities joined unions, but complete union solidarity was still lacking. Women were still in subordinate to men in unions and many separate ethnic and racial unions were organized.[37] Labour radicalism began to take root, but was suppressed after the Winnipeg General Strike. Some radicalism continued after the founding of the Communist Party of Canada in 1921, but it was limited. Many of the strike leaders were sentenced to prison terms as the federal government feared a Bolshevik uprising. Requests for collective bargaining by unions were rejected throughout the country, and especially in Manitoba.

The prevailing opinion amongst contemporary labour leaders and later historians is that the war severely weakened labour’s cause in the immediate post-war years after minor gains during the war. The reasons for the suppression of labour in the post-war period are still hotly debated. Desmond Morton posits labour weakness as one reason for the suppression:

Others believe the federal government used the war as an excuse to begin targeting radical labour leaders and groups. One example is the death of Albert “Ginger” Goodwin (1887-1918), a labour leader who was killed on 27 July 1918 while evading conscription in the hills of British Columbia. Gregory Kealey claims the state had hidden its anti-working-class stance prior to the war, but that the measures introduced in the late war and post-war period revealed its true intentions to suppress radical labour movements.[39] Whatever the catalyst for this decline, the war negatively affected labour in Canada.

Brad St. Croix, University of Ottawa

Section Editor: Tim Cook

Notes

- ↑ Heron, Craig: The Canadian Labour Movement. A Short History, Toronto 2012, pp. 32-33.

- ↑ Morton, Desmond: Canada and War. A Military and Political History, Toronto 1981, p. 57.

- ↑ Drache, Daniel: The Formation and Fragmentation of the Canadian Working Class. 1820-1920, in: Bercuson, David J. / Bright, David (eds.): Canadian Labour History. Selected Readings, Toronto 1994, p. 25.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 6.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 27.

- ↑ Heron, Canadian Labour Movement 2012, p. 31.

- ↑ Heron, Canadian Labour Movement 2012, p. 47.

- ↑ McCalla, Douglas: The Economic Impact of the Great War, in: Mackenzie, David (ed.): Canada and the First World War. Essays in Honour of Robert Craig Brown, Toronto 2005, p. 143.

- ↑ Street, Kori: Patriotic, Not Permanent. Attitudes about Women’s Making Bombs and Being Bankers, in: Glassford, Sarah / Shaw, Amy (eds.): A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service. Women and Girls of Canada and Newfoundland during the First World War, Vancouver 2012, p. 150.

- ↑ Sangster, Joan: Mobilizing Women for War in: Mackenzie, David (ed.): Canada and the First World War. Essays in Honour of Robert Craig Brown, Toronto 2005, p. 169.

- ↑ Street, Patriotic, Not Permanent 2012, p. 150.

- ↑ Morton, Desmond: When Your Number’s Up. The Canadian Soldier in the First World War, Toronto 1992, p. 287.

- ↑ Heron, Craig: National Contours. Solidarity and Fragmentation, in: Heron, Craig (ed.): The Workers’ Revolt in Canada 1917-1925, Toronto 1998, p. 270.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 288.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 269.

- ↑ McKay, Ian / Morton, Suzanne: The Maritimes. Expanding the Circle of Resistance, in: Heron, Craig (ed.): The Workers’ Revolt in Canada 1917-1925, Toronto 1998, p. 47.

- ↑ Naylor, James: Southern Ontario. Striking at the Ballot Box, in: Heron, Craig (ed.): The Workers’ Revolt in Canada 1917-1925, Toronto 1998, p. 147.

- ↑ McKay, Ian: Reasoning Otherwise. Leftists and the People’s Enlightenment in Canada, 1890-1920, Toronto 2008, p. 433.

- ↑ Heron, The Workers’ Revolt 1998 , p. 183.

- ↑ Kealey, Gregory S.: 1919. The Canadian Labour Revolt, in: Bercuson, David J. / Bright, David (eds.): Canadian Labour History: Selected Readings, Toronto 1994, p. 197.

- ↑ Brown, Robert Craig / Cook, Ramsay: Canada 1896-1921. A Nation Transformed, Toronto 1974, p. 242.

- ↑ Library and Archives Canada, Orders in Council 19 September 1918 to 28 September 1918 (RG2), 2168E, v. 955, P.C. 2384, September 1918.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Kealey, Gregory S.: State Repression of Labour and the Left in Canada, 1914-20. The Impact of the First World War, in: Canadian Historical Review 73/3 (1992), pp. 291-292.

- ↑ Morton, Working People 1988, p. 111.

- ↑ Cook, Tim: Warlords. Borden, Mackenzie King, and Canada’s World War, Toronto 2012, p. 117.

- ↑ McKay, Reasoning Otherwise 2008, p. 422.

- ↑ For a good example of this more traditional view, see Auger, Martin: On the Brink of Civil War. The Canadian Government and the Suppression of the 1918 Quebec Easter Riots, in: Canadian Historical Review 89/4 (2008), pp. 503-540.

- ↑ Auger, On the Brink 2008, p. 519.

- ↑ Mann, Jatinder: To the last man and the last shilling and Ready, aye ready. Australian and Canadian Conscription Debates during the First World War, in: Australian Journal of Politics and History 61/2 (2015), p. 195.

- ↑ Mitchell, Tom / Naylor, James: The Prairies. In the Eye of the Storm, in: Heron, Craig (ed.): The Workers’ Revolt in Canada 1917-1925, Toronto 1998, p. 215.

- ↑ Morton, Desmond: Working People. An Illustrated History of the Canadian Labour Movement, Montreal et al. 1998, p. 119.

- ↑ McKay, Reasoning Otherwise 2008, p. 460.

- ↑ Morton, Canada and War 1981, p. 87.

- ↑ Morton, Working People 1988, p. 122.

- ↑ McKay, Reasoning Otherwise 2008, pp. 460-461.

- ↑ Heron, National Contours 1998, p. 271.

- ↑ Morton, Working People 1998, p. 124.

- ↑ Kealey, State Repression of Labour 1992, p. 314.

Selected Bibliography

- Auger, Martin F.: On the brink of civil war. The Canadian government and the suppression of the 1918 Quebec Easter Riots, in: Canadian Historical Review 89/4, 2008, pp. 503-540.

- Brown, Robert Craig / Cook, Ramsay: Canada, 1896-1921. A nation transformed, Toronto 1974: McClelland and Stewart.

- Cook, Tim: Warlords. Borden, Mackenzie King, and Canada's world wars, Toronto 2012: Allen Lane.

- Drache, Daniel: The formation and fragmentation of the Canadian working class. 1820-1920, in: Bercuson, David Jay / Bright, David (eds.): Canadian labour history. Selected readings, Toronto 1994: Copp Clark Longmans, pp. 4-46.

- Heron, Craig: National contours. Solidarity and fragmentation, in: Heron, Craig (ed.): The workers’ revolt in Canada 1917-1925, Toronto 1998: University of Toronto Press, pp. 268-304.

- Heron, Craig: The Canadian labour movement. A short history, Toronto 2012: James Lorimer & Co..

- Kealey, Gregory S.: State repression of labour and the left in Canada, 1914-20. The impact of the First World War, in: The Canadian Historical Review 73/3, 1992, pp. 281-314.

- Kealey, Gregory S.: The Canadian labour revolt, in: Bercuson, David Jay / Bright, David (eds.): Canadian labour history. Selected readings, Toronto 1994: Copp Clark Longmans, pp. 193-222.

- Library and Archives Canada, Orders in Council 19 September 1918 to 28 September 1918 (RG2), 2168E, v. 955, P.C. 2384, September 1918.

- Mann, Jatinder: 'To the last man and the last shilling' and 'Ready, aye ready'. Australian and Canadian conscription debates during the First World War, in: Australian Journal of Politics & History 61/2, 2015, pp. 184-200.

- McCalla, Douglas (ed.): The economic impact of the Great War: Canada and the First World War. Essays in honour of Robert Craig Brown, Toronto; Buffalo 2005: University of Toronto Press, pp. 138-153.

- McKay, Ian: Reasoning otherwise. Leftists and the people's enlightenment in Canada, 1890-1920, Toronto 2008: Between the Lines.

- McKay, Ian / Morton, Suzanne: The maritimes. Expanding the circle of resistance, in: Heron, Craig (ed.): The workers’ revolt in Canada 1917-1925, Toronto 1998: University of Toronto Press, pp. 43-86.

- Mitchell, Tom / Naylor, James: The prairies. In the eye of the storm, in: Heron, Craig (ed.): The workers’ revolt in Canada 1917-1925, Toronto 1998: University of Toronto Press, pp. 176-230.

- Morton, Desmond: Working people. An illustrated history of the Canadian labour movement, Montreal 1998: McGill-Queen's University Press.

- Morton, Desmond: Canada and war. A military and political history, Toronto 1981: Butterworths.

- Naylor, James: Southern Ontario. Striking at the ballot box, in: Heron, Craig (ed.): The workers’ revolt in Canada 1917-1925, Toronto 1998: University of Toronto Press, pp. 144-175.

- Sangster, Joan: Mobilizing women for war, in: MacKenzie, David Clark (ed.): Canada and the First World War. Essays in honour of Robert Craig Brown, Toronto; Buffalo 2005: University of Toronto Press, pp. 157-193.

- Street, Kori: Patriotic, not permanent. Attitudes about women's making bombs and being bankers, in: Shaw, Amy J. / Glassford, Sarah Carlene (eds.): A sisterhood of suffering and service. Women and girls of Canada and Newfoundland during the First World War, Vancouver; Toronto 2012: UBC Press, pp. 148-170.