Introduction↑

The sudden outburst of the war in summer 1914 shook up many pre-war social and political structures. One of these was the French labour movement, which was strongly affected by the general mobilisation and the sudden transition to wartime economy.

In French historiography, the first studies of the labour movement during the Great War date from the 1960s and were conducted by a generation of historians who looked primarily into the movement’s political dimensions. These historians examined the changes that took place in different branches of the labour movement: socialists, syndicalists, and anarchists. Their studies aimed to understand how the conflict paved the way for communism.[1] In the 1980s and 1990s, principally Anglophone historians conducted many innovative studies on the French labour movement; they focused on social dimensions such as gender, family, women’s work, pacifism, and other social struggles.[2]

An analysis of the 1914-1918 labour movement was not published in France until 1995. It was written by the historian Jean-Louis Robert,[3] who approached the movement from a social angle, enabling an understanding of the social experience of the workers facing the conflict in the Paris region. This point of view had been neglected up until then.

This paper has two objectives. First, to analyze the changes that the different groups of the French labour movement underwent beginning in 1914, particularly with respect to the question of peace. Second, to map out the workers’ experience of the new working conditions as well as their complex relationship to state authorities, who did not hesitate to take severe measures against the workers’ social or political actions of protest.

The French Labour Movement Facing the War↑

From Acceptance to Refusal↑

During the general mobilisation in August 1914, French socialists, syndicalists, and even revolutionary anarchists immediately suspended the class struggle and internationalistic proletarian solidarity in order to support their country, which they considered to be a victim of German aggression. Consequently, the ideas of pacifism and general strike were instantaneously replaced by an acceptance of the war objectives. This acceptence among working-class people, and particularly in the Confédération générale du travail (CGT), or General Confederation of Labour, led the minister of the interior, Louis Malvy (1875-1949), to send a telegramme on 1 August 1914 to the prefects in which he instructed them not to follow through on the Carnet B,[4] a list with the names of militants – mainly revolutionary syndicalists and anarchists – suspected of potentially sabotaging the possible national mobilisation.

The pacifist activity,[5] so intense in the preceding years at the conferences of the International, now faded out. In 1914, only a few individual voices were raised against the war, notably those of the syndicalist Pierre Monatte (1881-1960) and the anarchist Sébastien Faure (1858-1942). But in the spring of 1915, a pacifist awakening could be noticed – still very limited and moderate – among certain groups within the labour movement: a minority of socialists, syndicalists and anarchists, as well as women’s socialist organisations.[6]

Within the Socialist Party (PS), a minor opposition appeared, very soon labelled minor since it was opposed to the majority of the party, led by Jean Longuet (1876-1938). Socialist pacifism was first launched by the socialist federation of the Haute-Vienne, one of the most important socialist federations. On 15 May 1915, this federation distributed a circular written by the federal secretary and signed by fifteen councillors and assistants to the mayor of Limoges. It was addressed to three groups: the permanent administrative commission (CAP) of the French section of the Workers’ International (SFIO), the socialist deputies, and the socialist federations.

The main questions raised referred to the prolongation of the war, its objectives, and the attitude on the war taken by the PS and labour circles. It called on the PS to pay attention to any peace proposal, from any quarter, with the prerequisite that the Belgian and French territories were not to be contested in the course of the discussions; furthermore, the circular required the CAP to try and reestablish closer and continuous contacts between the different branches of the party.[7]

Simultaneously, a syndicalist protest began to form, mainly emanating from the metallurgic workers’ federation, led at this time by Alphonse Merrheim (1871-1925) and Albert Bourderon (1858-1930). These two syndicalists were among the pioneers of French pacifism in the years 1914-1918. In November 1915 they founded the Committee for International Action (CDS), an organisation that rallied syndicalist and anarchist militants. Merrheim and Bourderon had attended the first conference of the International on 5-9 September 1915, which took place at Zimmerwald, while the PS had refused to send delegates.

This conference was of particular importance because of a brochure adopted at its closing. The brochure listed the Zimmerwald resolutions and manifesto, along with another text entitled French-German Declaration Common to French and German Socialists and Syndicalists, signed by the German and French delegations who declared that “This war is not our war.” The Zimmerwald manifesto constituted the first international and collective opposition against the majority who supported the war.[8]

However, at the very beginning of 1916, the Committee for International Action was dissolved in the wake of conflicts between syndicalists and anarcho-syndicalists. The syndicalists then formed a new framework struggling for peace, The Committee for the renewal of International Relations (CRRI).[9]

In 1916, the labour movement minority’s protests grew stronger and reached a peak with the second international socialist conference held at Kienthal in Switzerland from 24-30 April 1916.[10] On this occasion too, the French socialist party refused to send an official representative, declaring that the moment had not come for a renewal of international relations. Three socialist deputies – Pierre Brizon (1878-1923), Alexandre Blanc (1874-1924), and Jean-Pierre Raffin-Dugens (1861-1946) – defied this declaration and, on their own initiative, participated in their private capacity as non-official observers. The conference closed with the adoption of the manifesto Aux peuples qu’on ruine et qu’on tue! ("To the Peoples who are Brought to Ruin and Killed!"), the core of which was written by Brizon.

The CRRI aimed to develop a meeting place where socialists and syndicalists protesting against the war could cooperate. But they failed to reach this goal; no common activities took place and in the summer of 1916, the differences between the two sections of the committee were exposed. In the centre of the controversy was the question of what position to take regarding the international meetings organised by the Swiss and Italian socialists.

On 20 December 1916, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) requested that the belligerent countries formulate their war objectives, in particular their views on the conflict’s outcome and the guarantees necessary to avoid new hostilities. This proposition roused lively interest among socialists, both pacifists and those who wanted to continue the war. It contributed to a degree of harmonisation between the two groups. However, one decisive bone of contention was not to be overcome: for the pacifists, Wilson’s proposition could enable peace negotiations, while the majority of the socialists considered a Labour International gathering out of the question.

Nevertheless, the idea of peace was from now on no longer limited to a minority of the socialists or the Zimmerwaldians; a number of socialists within the majority started protesting in parliament. Despite their hesitance, yet another place where the war was questioned – or, more precisely, the war’s prolongation rather than the national defence itself – had emerged.

The Russian Revolution and the Stockholm Conference: New Hope for Peace?↑

While both the PS minority and majority were making cautious approaches, a veritable volcanic eruption caused great confusion in the French International: the Russian revolution had broken out.

The Bolshevik experience showed the French labour movement another revolutionary reality. After the 1914 shock, this second ordeal aggravated the internal crisis caused by the war. For the left-wing Zimmerwaldian faction, the October Revolution appeared as a glimpse of hope, but the French labour movement shrank from such a radical means of ending the war and instead took up a position between the dominating nationalist majority and the revolutionary pacifists, thereby choosing a perspective similar to that of the socialist minority since the spring of 1915.

The socialist minority, in turn, did not want a separate peace with Germany to be signed and viewed the revolution rather as an opportunity to encourage activities in the international proletariat that could favour rapid reestablishment of peace.

Almost at the same moment another event of great concern to all branches of the labour movement occurred, namely the announcement of another internationalist conference, to take place in Stockholm on 3 June 1917. The initiative came from German socialists but had been originally suggested by the Russian socialists. Contrary to the conferences of Zimmerwald and Kienthal, this one aroused great interest not only among militant pacifists but also in wider circles. However, each branch had specific expectations and objectives for the coming conference. The Zimmerwaldians looked upon it as a means of making peace “outside and face to face with the governments.” For the minority it was an opportunity to “revitalize the International.” The majority, previously hostile to internationalist conferences, welcomed the initiative, considering it a factor in promoting peace.[11]

Although the Stockholm project itself had not yet been realised, the conference itself turned out to be much more fruitful than those at Zimmerwald or Kienthal, since it helped to bring the internationalist circles closer. The Stockholm initiative consolidated a common ground where the socialist majority and minority could agree on a “centrist” pacifism. It was also this development that widened the gap in the CRRI, inasmuch as it made cooperation between the minority of socialists and militant Zimmerwaldians impracticable. The latter grew still more radical and started sliding towards “defeatism.” At the other extreme of French socialism, the right-wingers regarded the Stockholm initiative as a “German plot.”

After 1918, the war problem was eliminated for the French labour movement. However, the approaching end of the war forced the PS and the CGT to face the question of revolution, an offspring of the conflict. As a matter of fact, both organisations were already searching for a centrist solution, found by adopting the American plan for peace drawn up by President Wilson and by refusing to end the war the Russian way, i.e. with a revolution. This choice led away from the nationalistic right and radical left.

Little by little, the socialist minority had evolved into a majority at the PS national congress held in Paris between 6-10 October 1918; thus, towards the end of the war the former relations had been inverted. In summarising the breaches in the International that had taken place through the shock of the war, together with the remoulding of the labour movement just before the congress of October 1918, one finds that French socialism was at this point divided into four sections: a right-wing section demanding that Germany be crushed; a centrist section embracing the Wilsonian perspective; another minor centrist section, and the left-wing Zimmerwaldians.

Revolution was at the core of all debates, causing violent polemics, while the centrists focussed on neutralizing the Zimmerwaldians rather than coming to an agreement with the former majority.[12] On the other hand, the Zimmerwaldians became more radical and continued to emphasise the problems of peace and war.

Other minor groups at the end of 1918 adhered to the extremely left-wing Zimmerwaldian pacifism. At that time, the pacifist movement was associated with a radical position, revolutionary as well as defeatist. During the last few months of the war, the internationalist revolutionaries realised that the peace conditions imposed on the adversary risked becoming germs of a future malicious conflict.

The Workers’ Experience: Crises, Strikes, and Repression↑

Rather than getting absorbed in the political and ideological issues, both male and female workers were more concerned about their material subsistence. The total war had strained the economy to the utmost degree, particularly the industry mobilised to meet the war demands. As John Horne has indicated, the industrial mobilisation put workers in the middle of war:[13] men were exempted from military service and women became a valuable work resource.

This new reality was not without consequences for the proletarian world. The move towards the industrial centres caused housing problems involving increased prices and a higher cost of living, especially in terms of food and coal, thereby making housekeeping more precarious. Moreover, social norms were suspended and the burden of work grew still heavier. Strikes began to appear in industrial urban areas. These first manifestations were amplified and eventually led to violent outbursts in 1917 and 1918, when female workers went on spontaneous strikes in May, June and mid-July 1917.[14]

Women in Action: Social Strikes↑

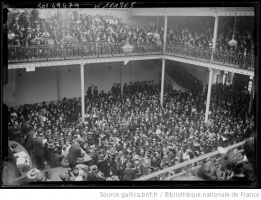

A few weeks after the disastrous failure of the Chemin des Dames offensive on 11 May 1917, the seamstresses were the first to go on strike. These were spontaneous strikes. As Jean-Louis Robert noted, there was no hint at the possibility of a strike[15] at the syndicalist reunions at the beginning of May 1917. There were no political motives to trigger the strikes; they were not attributable to any pacifist fight, but were rather a consequence of social claims. The strike meetings were held mainly at the Bourse de Travail. However, no plans were made in advance. In fact, the syndicalist representatives took on themselves to “mediate” with the authorities[16] in order to present the workers’ claims. These manifestations were ruthlessly repressed: truncheons, violence, bites from police dogs, imprisonment. For the authorities, it was simply a subversive revolt, nothing else.

This unrest had a deep impact on labour circles. It widened the rift in the innermost syndicalist circles and led the authorities to take violent repressive measures. Among the first to bear the consequences were the revolutionary militants, who were hit by a number of measures: the Paris prefecture suppressed all their rights to gathering as early as 12 July 1917. The authority also ordered the Bourse de Travail to close their doors to non-unionised organisations, otherwise it would have to be closed down. Finally the syndicalist Defence Committee was forbidden all means of propagandist circulation.

In October 1917, the socialist congress of Bordeaux tried to find new directions in order to build a platform for the party’s politics. This goal necessitated convincing the different socialist branches to accept a centrist position. In the same way, the Clermont-Ferrand syndicalist congress on 23-25 December 1917 marked a willingness to dissociate itself from extremism while searching for a similar position. The majority of the syndicalists now rallied around the idea of an international peace conference. From now on, the minority groups were divided, incapable of working out a solid project that would unify different perspectives.

The 1918 Pacifist Strikes↑

“Neither treason nor semi-treason but war. Nothing but war,”[17] proclaimed the new French president, Georges Clemenceau (1841-1929), in his ministerial declaration of November 1917. This declaration before the Chamber of Deputies announced war to the utmost degree against the “internal enemy,” mainly pacifists and antimilitarists originating from the labour movement.

The arrests of the militant pacifists made the various labour sections join ranks and defend their comrades in a struggle that was part of a larger one against Clemenceau’s politics. But the CDS delivered the strongest counteroffensive in this battle; in 1918, this committee was the only one to carry the banner of pacifism. It was, however, a “defeatist pacifism” represented by the extreme left and supporting the Bolshevik solutions.

The development of the labour movement towards a centrist position and the closer association between the syndicalist majority and minority contributed to the radicalisation of the CDS struggle. The workers should act for themselves “by a strike of hands, ammunition, and transport and pass to a strike of cannons and rifles, a general strike for peace, so as to force those in power to engage in peace negotiations.”[18]

In March 1918, the Loire syndicalists organised a meeting at Saint-Etienne to protest against the repression aimed at militant pacifists. On 24 March 1918, the Congress of the Union of syndicalists for the Loire department opened; the following day another opened with the participation of unions from eight surrounding departments.

The strikes in spring 1918 preceded the regional meetings. At a gathering on 19 and 20 May 1918 at Saint-Etienne, the CDS opted for a general strike given the unrest in the Parisian construction and metallurgic sectors. On 1 May 1918, between 15,000 and 20,000 people took to the streets; on 5 May 1918, the construction and metallurgic sectors in Paris also demonstrated. At the Renault factory and in the whole Parisian region, 105,130 of the 127,000 workers in the fifty-seven defence factories went on strike. Finally, on 18 May 1918, the most important strikes took place, voicing slogans such as “Down with war” or “Strike until armistice.” At Firminy, the disturbances were partiuclarly violent, hitting the industrial areas of the Loire department on 21 May 1918. More than 10,000 workers stopped work, calling for peace negotiations and an immediate armistice. The strikers insisted on the factories’ closure, an action that would constitute a “symbol of the wish to stop the war.” In the face of these troubles the government took rigorous measures against the instigators of the “mutinies” on the “interior front” who were accused of “abandoning their post, deserting within the country in wartime, exhorting to desertion, and complicity.”[19]

These strikes, unlike those of 1917, were clearly political and pacifist, both in their slogans and targets. It is obvious, as Jean-Jacques Becker pointed out, “that they reflect the pacifism of a fairly substantial fraction of the masses, but the course of events also show the uncertainty of pacifists who want peace but do not know how to achieve it.” Nevertheless, the workers refused defeatism: “The workers, being ‘pacifists,’ were not ‘defeatists,’” commented Becker justly. In the face of war, “one cannot be pacifist in the deepest sense of the word without being a revolutionary and without bearing the consequences, i.e. the possibility of defeat of one’s country, if the adversary is not willing to make peace.”[20]

The labour movement found itself in a sort of “vacuum” towards the end of the war, between the armistice and the peace treaties; more than seven months passed before certain circles within the movement were heard again. Only from the spring of 1919 on did the social claims reappear on the labour movement’s agenda.

The CRRI revolutionaries, particularly some Zimmerwaldians, were to be part of a kernel around which the Third International was crystallizing. The organisation was founded on 2-6 March 1919 by Vladimir Lenin (1870-1924) in Moscow and consisted of nineteen delegates from Central and East Europe. On 8 May 1919, the CCRI changed its name and became the Committee of the Second International, represented by Alfred Rosmer (1877-1964) during the Second Congress of the Third International, also called the Communist International (IC). On 30 December 1920, a number of the SFIO socialists participated in the Congress of Tours and declared themselves for the principles of the IC and its revolutionary spirit. The French Communist Party was founded and took the name Section Française de l’Internationale Communiste (SFIC).

Galit Haddad, Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales

Section Editor: Nicolas Beaupré

Notes

- ↑ Examples include Kriegel, Anne: Aux origines du communisme, 1914-1920. Contribution à l’histoire du mouvement ouvrier français, Paris et al. 1964; Becker, Jean-Jacques/Kriegel, Anne: 1914, la guerre et le mouvement ouvrier français, Paris 1962. See also Madelaine Reberieux’s works, which focus on Jean Jaurès but also on the working class culture. Regarding the anarchists and revolutionary syndicalism during the war, see: Maitron, Jean: Le Mouvement anarchiste en France, Paris 1975.

- ↑ Sowerwine, Charles: Sisters or Citizens. Women and Socialism in France since 1876, Cambridge 1982; Horne, John: Labour at War. France and Britain, 1914-1918, Oxford 1991.

- ↑ Robert, Jean-Louis: Les Ouvriers, La Patrie, La Révolution. Paris, 1914-1919, Paris 1995.

- ↑ See: Becker, Jean-Jacques: Le Carnet B. Les pouvoirs publics et l’antimilitarisme avant la guerre de 1914, Paris 1973.

- ↑ On pacifism in the labour movement during the war, see: Haddad, Galit: 1914-1919. Ceux qui protestaient, Paris 2012.

- ↑ The sources quoted in this article can be consulted in: Sowerine, Aude/Sowerine, Charles: Le mouvement ouvrier français contre la guerre, 1914-1918, 7 volumes, Paris 1985. This collection of seven volumes gathers the essentials of the labour movement protests (brochures, pamplets, flyers) distributed by women activists, socialist and syndicalist minorities or anarchist circles.

- ↑ Parti socialiste (S.F.I.O.), Fédération de la Haute-Vienne, Rapport (Federation of the Haute-Vienne), Imprimerie nouvelle, place Fontaine-des-Barres, Limoges, 15 May 1915.

- ↑ Letter to the subscribers of La Vie Ouvrière, La conférence de Zimmerwald (Letter to the La Vie Ouvrière [The Worker’s Life] Subscribers, The Conference of Zimmerwald), 96 Quai de Jemmapes, Paris, novembre 1915.

- ↑ Comité pour la reprisedes Relations internationales (CRRI)

- ↑ The CRRI published the text: Seconde conférence socialiste internationale de Zimmerwald. Held at Kienthal (Switzerland), 24-30 April 1916, foreword by Robert Grimm, Imprimerie spéciale du CRRI, Paris. On the second internationalist conference, see Humbert-Droz, Jules: L’Origine de l’International communiste. De Zimmerwald à Moscou, coll. “Histoire et société d’aujourd’hui”, Neuchâtel 1968, pp. 154-204.

- ↑ Becker, Jean-Jacques: Les Internationales et le problème de la guerre au XXe siècle, actes du colloque, Rome, 22-24 novembre 1984, Boccard 1987, p. 20.

- ↑ Kriegel, Aux origines 1964, p. 233.

- ↑ See the article by Horne, John: Ouvriers, mouvements ouvriers et mobilisations industrielles, in: Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane / Becker, Jean-Jacques (eds.): Encyclopédie de la Grande Guerre , Paris 1994.

- ↑ Jean-Louis Robert indicates that 32 percent of all wartime strikes occurred in the spring of 1917. See Robert, Les Ouvriers 1995, p. 137.

- ↑ Robert, Les Ouvriers 1995, p. 137.

- ↑ Robert, Les Ouvriers 1995, p. 138.

- ↑ Quoted in: Becker, Jean-Jacques: Clemenceau. L’intraitable, in: Levi, Liana (ed.): Curriculum, Paris 1998, p. 80, author’s translation.

- ↑ Letter from Raymond Péricat to Bonnefoy, 2 February 1918. Quoted in: Kriegel, Aux origines 1964, p. 209, author’s translation.

- ↑ Kriegel, Aux origines 1964, p. 209.

- ↑ Becker, Jean-Jacques: Les Français dans la Grande Guerre, Lafont 1980, p. 249, author’s translation.

Selected Bibliography

- Becker, Jean-Jacques: Le carnet B. Les pouvoirs publics et l'antimilitarisme avant la guerre de 1914, Paris 1973: Klincksieck.

- Chambarlhac, Vincent / Ducoulombier, Romain (eds.): Les socialistes français et la Grande Guerre. Ministres, militants, combattants de la majorité, 1914-1918, Dijon 2008: Éditions universitaires de Dijon.

- Droz, Jacques (ed.): Histoire générale du socialisme de 1875 à 1918, volume 2, Paris 1974: Presses universitaires de France.

- Ecole française de Rome / Università di Milano (eds.): Les Internationales et le problème de la guerre au XXe siècle. Actes du colloque de Rome, 22-24 novembre 1984, Collection de l'École française de Rome, Milan; Rome; Paris 1987: Ecole française de Rome.

- Haimson, Leopold H. / Sapelli, Giulio (eds.): Strikes, social conflict, and the First World War. An international perspective, Milan 1992: Fondazione Giangiacomo Feltrinelli.

- Horne, John: Ouvriers, mouvements ouvriers et mobilisations industrielles, in: Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane / Becker, Jean-Jacques / Horne, John (eds.): Encyclopédie de la Grande Guerre, 1914-1918. Histoire et culture, Paris 2004: Bayard, pp. 601-612.

- Horne, John: Labour at war. France and Britain, 1914-1918, Oxford; New York 1991: Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press.

- Humbert-Droz, Jules: L'Origine de l'internationale communiste. De Zimmerwald à Moscou, Histoire et société d’aujourd’hui, Neuchâtel 1968: Édition de la Baconnière.

- Kriegel, Annie / Becker, Jean-Jacques: 1914. La guerre et le mouvement ouvrier franc̜ais (1914. The war and the French labor movement), Paris 1964: Armand Colin.

- Kriegel, Annie: Aux origines du communisme français, 1914-1920. Contribution à l'histoire du mouvement ouvrier français, volume 2, Paris 1964: Mouton.

- Launay, Michel / Mouriaux, René: Le syndicalisme en Europe, Paris 1990: Imprimerie nationale.

- Maitron, Jean / Pennetier, Claude: Dictionnaire biographique du mouvement ouvrier français. 4e partie, 1914-1939, de la Première à la Seconde Guerre Mondiale, Paris 1981: Les Éditions Ouvrières.

- Moreau, Jacques: Les socialistes français et le mythe révolutionnaire, Paris 1998: Hachette Littératures.

- Noiriel, Gérard: Les ouvriers dans la société française, XIXème-XXème siècle, Paris 1986: Seuil.

- Robert, Jean-Louis: Les ouvriers, la patrie et la révolution. Paris 1914-1919, Paris 1995: Les Belles lettres.

- Sowerwine, Aude / Sowerwine, Charles: Le Mouvement ouvrier français contre la guerre, 1914-1918. Textes et documents, Paris 1985: EDHIS.