Labour↑

In Britain, and to a lesser extent in Ireland, the withdrawal of a large proportion of the male labour force into the Armed Forces put the remaining labour, whether unionized or not, in a strong position in the labour market. Patriotic support for the war ensured that this commanding position was not fully exploited, though organized labour did emerge much stronger.

During 1914-1918, 5,670,000 men were enlisted in the Armed Forces, which represented roughly 38 percent of the total pre-war male labour force. They were partly replaced by drawing on unemployed, elderly and returned expatriate men, additional women, prisoners of war and, at times such as harvesting, school children (by the end of May 1916, 15,753 had been given exemption from school). Women’s paid employment in Great Britain and Ireland rose by just about 23 percent during the war (when numbers of women aged above ten rose by just under 5 percent), with very marked changes within employment. Many women moved away from domestic service, textiles and clothing to transport, national and local government, banking and insurance, engineering and agriculture.

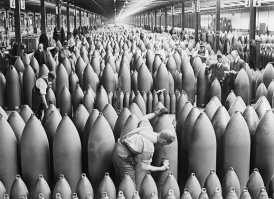

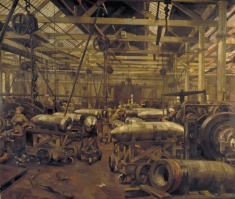

The war saw very substantial changes in employment as war work expanded and other sectors contracted. While overall civilian employment was reduced during the war, vital sectors such as engineering expanded. Even the number of male workers increased between July 1914 and July 1918, by 23 percent in engineering (excluding ordnance), while the number of female workers went up 670 percent. Examples of sectors where employment was reduced between July 1914 and July 1918 include building, down 49 percent (where women did not provide substantial numbers of replacements, rising from under 1 percent to 6 percent); cotton, down 27 percent (where women were already a majority of the labour force, but rising from 60 to 71 percent of the reduced workforce); and municipal services, including trams and teachers, down 15 percent (where the proportion of women rose from 31 to 46 percent).[1]

Voluntary recruiting secured large numbers of men but it was indiscriminate in its incidence. Before the start of conscription in January 1916, some 2.4 million men volunteered for the army. Most of these (some 2 million) had enlisted in the first year, and many came from what was priority war work. So by July 1915, 24 percent of chemical and explosive workers, 24 percent of electrical engineers, 22 percent of miners and 20 percent of engineers had gone.[2] This exacerbated skill shortages that would have occurred even without the loss of the volunteer recruits. Following conscription from January 1916 onward there was increased control that ensured that people were not recruited from high priority civilian work. On 31 October 1918, there were 2,574,860 men in Reserved Occupations; the largest numbers were in munitions, ship building and repairing (1,032,181), coal mining (502,709), transport (401,641) and agriculture (540,506).[3]

The Government and Labour Supply↑

After discussions in the autumn of 1914 between employers and trade unions failed to agree on measures to increase output with the reduced available skilled labour, the government arranged the Shell Conference on 21 December 1914. Other government initiatives followed, the most important of which were the setting up of the Committee on Production on 4 February 1915, which became a major force in labour matters, and the Treasury Conference of 17-19 March 1915. At this conference, the major trade unions other than the miners reached a voluntary agreement with the government to suspend restrictive practices and to settle disputes by arbitration, not by strikes. At a separate meeting, employers agreed to limit profits in munitions works controlled by the Defence of the Realm Acts (DORA).

Reliance on voluntary agreements swiftly crumbled in the face of growing labour shortages and unsatisfactory increases in the output of war materials. By June 1915, there were 48,000 fewer engineering workers than before the outbreak of the war and munitions factories were some 14,000 workers short of their requirements. The largely laissez-faire state and economy of pre-war years gradually evolved into a heavily interventionist state and a largely controlled economy. With the Munitions of War Act on 2 July 1915, the voluntary arrangements agreed at the Treasury were given the force of law. There were measures designed to increase labour mobility in order to benefit war work, restrict labour from leaving priority work by requiring leaving certificates (which stated that they were no longer required), dilute labour (in order to allow less skilled labour to do skilled work), stop bad timekeeping and other costly workplace misdemeanours through special industrial courts called munitions tribunals, and ban strikes and lockouts. The Act made the Committee on Production an arbitration tribunal, and it and individual arbitrators resolved many disputes.[4] The Munitions of War Acts and Amendments were extended across most of British industry and, with the Defence of the Realm Acts, were the means by which the state exercised control. Labour was also affected by powers over wages among the provisions of the Corn Production Act of 1917, which like the Munitions of War Act was of much wider scope than its title suggests.

Although the British state had extensive powers over labour under DORA and the Munitions Acts, the needs of the war and the strong position of labour often made it difficult for the government to enforce its legal measures. As in the Second World War, the government found that the vital need for coal made coercion against miners’ collective action unrealistic. In the First World War this was notably so in the case of striking miners in South Wales in July 1915; David Lloyd George (1863-1945) chose to concede to most of the miners’ demands. The government also faced many strikes in engineering over changed working practices and private profits on war work. Wartime inflation, shortages of food and overcrowding in munitions areas added to industrial discontent. Generally, however, the widespread support for the war ensured less conflict than might have occurred outside of war. In the big cities, rent controls from 1915 and limited rationing of food from 1917 made it possible to avoid the more severe hardship experienced in cities such as Petrograd, Moscow, Berlin and Vienna.

Trade Unions↑

United Kingdom trade unionism had roughly doubled between 1900 and 1913. It nearly doubled again by 1920 in terms of union density (the proportion of union members out of those legally eligible to join), a level not matched until 1950. The First World War had the impact on trade union membership of a big upturn in a trade cycle; in a full labour market, the unions were able to negotiate higher wages and better working conditions. However, for many people these higher rates of pay were offset by the cost of living rising faster than basic wages, but at the same time mitigated by extra payments for longer working hours, and in some cases by bonuses. Trade unionism was further boosted by the fact that the government required collective agreements in many industries and insisted that employers recognize the unions. Such state recognition, often followed by the successful negotiation of war bonuses, boosted trade union membership in hitherto weakly organized industries such as hosiery in the Midlands and jute in Dundee.

UK trade union membership rose from 3,708,000 (29.5 percent density) to 5,324,000 (41.8 percent), a rise of 43.6 percent. Trade union membership among women, which had grown by 140.6 percent between 1905 and 1913, rose by 176.7 percent between 1914 and 1918 (density rising from 8.0 to 15.9 percent), so that a little under one in five trade unionists were female. Even with a reduction of labour in building and cotton and flax, British union membership in these sectors increased by 74.6 and 15.7 percent respectively. In key wartime areas, such as metals and engineering, a relatively strongly unionized area in the pre-war period (1911 density of 29.2 percent); chemicals, a relatively weakly unionized area prewar (1911 density of 9.6 percent); and railways (1913 density of 42.8 percent), union membership went up by 108.8, 156.7 and 56.9 percent respectively. Another key area, coal mining, had been strongly unionized prior to the war (1911 density of 74.1 percent), yet during the war union membership grew by 17.5 percent. The war saw trade unionism grow in several hitherto weakly organized sectors. In agriculture, where union density had been 0.1 percent in 1911, during the war union membership grew by 343.9 percent, much of this growth being due to the Corn Production Act. Another weakly unionised area, clothing (1911 union density of 6.0 percent), saw a 140.8 percent increase in trade union membership. More generally, the war saw notably higher unionization among manual workers, an increase of 57.6 percent to 5,645,800, while unionization grew by 58.3 percent among white-collar workers to a membership of 815,600.[5]

In Britain, trade unions became involved in helping the war effort at all levels, from the Trades Union Congress (TUC) to local trades councils. At the national level, the TUC went well beyond delegations awaiting junior ministers to being consulted on a range of issues at the highest levels of government.[6] So much so that the greater trade union power and the national pay awards made by the Committee on Production led the diverse employers’ organizations to form the unified Federation of British Industries in 1916; the chair of the first meeting observed that "we have much to learn from labour."[7]

However, trade union involvement in carrying out dilution and other changes in working practices often led to conflict between union leaderships and their members who experienced the changes at their workplaces. In the coal industry, the government pressed the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain (MFGB) to create pit committees to police absenteeism and fine offenders. In some areas, no committees were created, and in a few places where they were, they were used to discuss wider issues of coal production.[8] Pit committees, however, were much milder alternatives to munitions tribunals, which covered the wide range of war work carried out in controlled establishments under the Munitions Acts. Ten general munitions tribunals were set up to deal with major issues, with fifty-five local munitions tribunals to deal with lesser matters. One of the most notable features of these tribunals was the large volume of cases that they dealt with; in the first three months of 1916 5,828 cases were heard at the busiest twenty-one local tribunals.[9] Yet little legal action was taken against strikers. In the first year of the tribunals only 1,006 people were convicted of striking and £1,365 collected in fines.[10] Taking employees to court was not likely to enhance industrial relations in employers’ workplaces. Those workers summoned before the tribunals were charged with a wide range of breaches of workplace rules, including bad timekeeping and departing without leaving certificates. Munitions tribunals could be used by militant workers to condemn employers, but, like later employment tribunals, they were also notable venues for local union officials to work for their members.

One major source of discontent was dilution. Many skilled male engineers were hostile to unskilled labour, male or female, doing skilled work. On Clydeside, in particular, there were major strikes involving combinations of conservative craftsmen with socialist craftsmen, who denounced state restrictions on labour that enabled huge private profits. The Clydeside dilution strikes, along with rent strikes arising from overcrowding and high rents in munitions areas, became a feature of Communist Party history. Such accounts portrayed successful militant rank-and-file action contrasted with trade union officials’ supine collaboration in adverse changes. These actions could be portrayed as precursors of the Communist Party of Great Britain’s minority movement campaign of the 1920s. Militant rank-and-file trade unionists’ dilution struggles were features of Willie Gallagher’s (1881-1965) 1936 reminiscences, Revolt On The Clyde. This was reinforced by scholarly works such as Branco Pribicevic’s The Shop Stewards’ Movement and Workers’ Control 1910-1922 and James Hinton’s The First Shop Stewards’ Movement. Such views were criticized by Alastair Reid, based on his research on shipbuilding. He argued that "the importance of dilution and independent shop floor organization has been exaggerated, even in the case of engineering", with "only on the Clyde is there any evidence that dilution was a contentious issue or that it produced a strong impulse towards independent shop floor organisation." He also argued that "there was no serious revolutionary crisis and no sustained government strategy to contain it."[11] Iain McLean also doubted notions of revolutionary Clydeside, while Jonathan Zeitlin was highly critical of rank-and-file interpretations.[12] Few now would argue that there was a revolutionary crisis in munitions or generally at Clydeside or elsewhere, or that the local trade union officials were generally out of touch with their members. However, there is a good case for believing that the government was determined to deal firmly with dissent affecting war production and there were militant shop stewards beyond the Clyde in engineering centres such as Sheffield and Coventry.[13] Some historians have argued that the strategy of the state was corporatist since it involved trade unions and employers in managing industrial relations.[14]

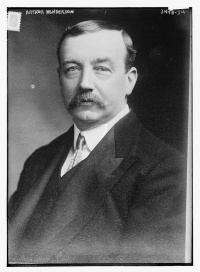

As in all belligerent countries, as the war dragged on there was growing war weariness among some of the population. At the outset, many in the British Labour movement had been highly critical of the secret diplomacy that they believed had led to war. Arthur Henderson (1863-1935), the chairman of the Parliamentary Labour Party after James Ramsay MacDonald’s (1866-1937) resignation at the outbreak of the war, joined the Union of Democratic Control (UDC) and stayed a member until joining the coalition government in May 1915. While trade union leaders like Henderson supported the recruiting campaign, there was a substantial minority of trade unionists who opposed the war and resisted conscription, joining such bodies as the No Conscription Fellowship. They made their opposition known in trade union branches and trades councils in South Wales, Clydeside, Sheffield, Coventry and elsewhere. Women’s groups also played a major part in opposing the war. Cyril Pearce has shown in detail in his book Comrades in Conscience the widespread opposition to the war among socialists, trade unionists and nonconformists, both men and women, in Huddersfield.

In Ireland, there was growing trade union strength after the setback of the bitter 1913 Dublin strike. This was linked to the rising strength of nationalism. The Irish Trades Union Congress and Labour Party (ITUCLP), like the British TUC, opposed conscription. When the British government displayed what the Voice of Labour deemed to be "mad folly and madder perversity" in introducing a bill to extend conscription to Ireland, the ITUCLP joined with nationalist to call a general strike on 23 April 1918. This was a success: "The whole nation - outside Belfast – ceased work on Tuesday."[15] In Ireland, Labour abstained from putting up candidates in the 1918 general election.

Strikes↑

The outbreak of war saw a voluntary ending of strikes in progress. Widespread support for the war ensured less propensity to strike. There were even signs that when British forces were doing badly in the war there was less labour unrest than when the war was going well.[16]

For the years 1915-1918, the total number of days lost through disputes in the UK was only 41 percent of the total for 1912, the worst of the pre-war years. Industrial unrest worsened as the war went on, as real wages shrank in the face of inflation and as long working hours contributed to war weariness. 68 percent of days lost occurred in 1917 and 1918. In Britain, as in the other belligerent countries, state controls led to disaffection with the government, and not simply with employers. The greatest number of days lost was in engineering with a total of 5,224,000 – 31 percent of all days lost in 1915-1918. Mining was the other sector of substantial unrest, with 4,429,000 days lost – 26 percent of the total.[17]

The Labour Movement in Politics↑

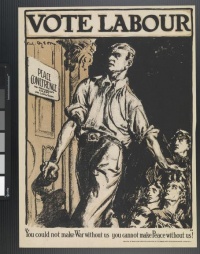

In June 1914, few people, if any, would have predicted that the Labour Party would form a government within ten years. The First World War transformed the Labour Party and its prospects. By 1917 leading political figures were talking of when, not whether, Labour would take office after the war. Before the war, the Labour Party had been in effect an auxiliary party to the Liberal Party. The war created deep fissures in the Liberal Party, which were not repaired in 1918-1926.

Trade unionists who served as members of parliament (MPs) were at the heart of the wartime Labour Party after Ramsay MacDonald and other ILP intellectuals resigned from the leadership at the outbreak of the war. Arthur Henderson entered the first coalition government as president of the board of education, with two others in lesser posts. He acted, as he had done from early in the war, as the key trade union facilitator of the government’s manpower and industrial relations policies. He later became paymaster-general, a post that gave him more time for labour matters. Under Lloyd George, from December 1916 to August 1917, he served in the small war cabinet. After his resignation over his desire for British representation at a socialist conference in Stockholm, he was replaced with another leading trade unionist MP, George Barnes (1892-1953). Labour’s appeal broadened to such issues as housing, food prices and supplies, decent treatment of soldiers’ dependants as well as a democratic peace settlement. Both nationally and locally the Labour Party, the trade unions and the co-operative movement stood for fairer shares in the war and after it. The Co-operative Party, founded in 1917, won its first seat in 1918.

Conclusion↑

Trade unions not only grew in size but also in financial strength. Expenditure on unemployed members fell and, as strikes were illegal, so did strike payments, while income rose rapidly. Trade union political levies grew after the 1913 Trade Union Act. In the case of the boilermakers’ union, its political fund rose from £500 in 1915 to just under £3,000 in 1918, when it sponsored five candidates in the general election. In all the unions directly funded half of Labour’s candidates, with the miners funding fifty-one, the Amalgamated Society of Engineers sixteen and the railway unions fifteen. Union finance was often critical in Labour’s electoral organization. A notable example was the County Durham constituencies, where, in 1918, the miners funded seventy-six sub-agents, 107 polling agents and 162 clerks.[18] Henderson, out of office, overhauled the Labour Party’s organization and contributed to its new, socialist constitution. As Henderson commented in 1920, Labour in 1918 "polled its minimum vote", 22.7 percent, but with fifty-seven MPs (sixty-one by the opening of Parliament) it was bigger than the opposition Liberals, with thirty-six MPs. The war gave Labour the impetus to transform its policies, its constitution and its organization, and so prepared it for government.

Chris Wrigley, University of Nottingham

Section Editor: Adrian Gregory

Notes

- ↑ Calculated from data in the Z8 inquiry, compiled by the Board of Trade and then by the Ministry of Labour. Buxton, N.K./MacKay, D.I.: British Employment Statistics, Oxford 1977, pp. 78ff.

- ↑ Wolfe, Humbert: Labour Supply and Regulation, Oxford 1923, online: https://archive.org/details/laboursupplyregu00wolfuoft (retrieved 16 April 2015); Dewey, P.E.: Military Recruiting and the British Labour Force during the First World War, in: The Historical Journal 27 (1984), pp. 199-223; Winter, J.M.: The Great War and the British People, London 1986, pp. 26-29.

- ↑ Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire during the Great War, 1914-1920, London 1922, p. 368, online: https://archive.org/details/statisticsofmili00grea (retrieved 16 April 2015).

- ↑ History of the Ministry of Munitions, Volume 1, Part 2, HMG, (unpublished but printed in 1923; later issued on microfilm); Wrigley, Chris: David Lloyd George and the British Labour Movement. Peace and War, Hassocks 1976, chapter 5.

- ↑ Bain, George Sayers/Price, Robert: Profiles of Union Growth. A Comparative Statistical Portrait of Eight Countries, Oxford 1980, pp. 37-67.

- ↑ Martin, Ross M: TUC. The Growth of a Pressure Group, 1868-1976, Oxford 1980, chapter 5; Clinton, Alan: The Trade Union Rank and File, Manchester 1977, pp. 54f.

- ↑ Proceedings of the Inaugural Meeting, 20 July 1916. Archives of the Federation of British Industries, Modern Record Centre, Warwick University Library, UK, MRC 200/F/3/D1/1/6.

- ↑ Cole, G.D.H.: Labour in the Coalmining Industry 1914-1921, Oxford 1923, pp. 40f and 68ff.

- ↑ Rubin, Gerry R.: War, Law and Labour. The Munitions Acts, State Regulation, and the Unions, 1915-1921, Oxford 1987, p. 41.

- ↑ Knowles, K.G.J.C.: Strikes. A Study in Industrial Conflict, Oxford 1952, p. 118.

- ↑ Reid, Alastair: Dilution, trade unionism and the state during the First World War, in: Tolliday, Steven/Zeitlin, Jonathan (eds.): Shop floor bargaining and the state. Historical and comparative perspectives, Cambridge 1985, pp. 46-74; Reid, Alastair: The Tide of Democracy. Shipyard Workers and Social Relations in Britain, 1870-1950, Manchester 2010.

- ↑ McLean, Iain: The Legend of Red Clydeside, Edinburgh 1983; Zeitlin, Jonathan: ‘Rank and Filism’ in British Labour History. A Critique, in: International Review of Social History 34 (1989), pp. 42-61.

- ↑ For instance, there are the details in the History of the Ministry of Munitions, 1923.

- ↑ For examples, see Middlemas, Keith: Politics in Industrial Society, London 1979, chapter 13, and Rubin, War, Law and Labour 1987, pp. 11-39 and 259-265.

- ↑ Voice of Labour, 13 April 1918, quoted in: Lindsay, Deirdre: Labour Against Conscription, in: Fitzpatrick, David (ed.): Ireland And The First World War, Mullingar 1986, p. 81; ILPTUC, 1918 Report, quoted in: Morgan, Austen: Labour And Partition. The Belfast Working Class 1905-23, London 1991, p. 195.

- ↑ Knowles, Strikes 1952, pp. 159f.

- ↑ Mitchell, B. R.: British Historical Statistics, Cambridge 1988, p. 144.

- ↑ Wrigley, Chris: Labour and the Trade Unions, in: Brown, K.D. (ed.): The First Labour Party 1906-14, London 1985, pp. 145ff; Tanner, Duncan: Political Change and the Labour Party 1900-1918, Cambridge 1990, pp. 403 and 465.

Selected Bibliography

- Bain, George Sayers / Price, Robert: Profiles of union growth. A comparative statistical portrait of eight countries, Oxford 1980: B. Blackwell.

- Bush, Julia: Behind the lines. East London labour, 1914-1919, London 1984: Merlin Press.

- Clegg, Hugh Armstrong (ed.): A history of British trade unions since 1889, 1911-1933, volume 2, Oxford 1985: Clarendon Press.

- Cronin, James E.: Industrial conflict in modern Britain, London; Totowa 1979: Croom Helm; Rowman and Littlefield.

- Hinton, James: The first shop stewards' movement, London 1973: G. Allen & Unwin.

- McKibbin, Ross: The evolution of the Labour Party, 1910-1924, London; New York 1974: Oxford University Press.

- Pearce, Cyril: Comrades in conscience. The story of an English community's opposition to the Great War, London 2001: Francis Boutle Publishers.

- Reid, Alistair J.: The tide of democracy. Shipyard workers and social relations in Britain, 1870-1950, Manchester; New York 2010: Manchester University Press.

- Rubin, Gerry R.: War, law, and labour. The Munitions Acts, state regulation, and the unions, 1915-1921, Oxford; New York 1987: Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press.

- Winter, Jay: Socialism and the challenge of war. Ideas and politics in Britain, 1912-18, London; Boston 1974: Routledge & K. Paul.

- Wrigley, Chris: David Lloyd George and the British labour movement. Peace and war, Hassocks; New York 1976: Harvester Press; Barnes and Noble Books.

- Wrigley, Chris: A history of British industrial relations, 1914-1939, Brighton 1987: Harvester Press.