Background and Origins↑

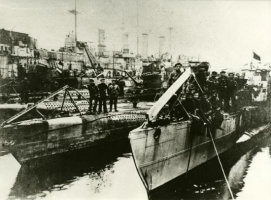

On 3 October 1918 the new German government led by Prince Max von Baden (1867-1929) initiated an exchange of diplomatic notes with US President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924). In his first note, Prince Max requested that Wilson bring an end to the war upon the basis of his fourteen points. The leadership of the German Navy was shocked by this prospect and refused to believe that Germany was defeated. Over the course of the remainder of the month, as the diplomatic exchange of notes began to discuss terms of an Armistice, led by Admiral Reinhard Scheer (1863-1928), the German Navy’s highest command set in place secret plans for a major naval assault upon the Royal Navy. The men behind the operation were especially worried by the prospect that their ships, built at tremendous cost since the turn of the century, would be surrendered to Britain as part of an Armistice deal. They also feared that the officer corps would lose honour if the war came to an end without the full deployment of the surface fleet, something that had been considered too great a risk up to this point in the war. Some of the leading voices calling for the operation also considered it possible that the navy’s sacrifice could reignite the German population’s “will” to continue the war. Although they were unaware of the operational plan, a significant number of sailors and stokers grew worried by the preparations and they began a small-scale mutiny during the final days of October 1918. Some of them simply refused to follow orders and took absence of their ships, while others sabotaged their ships’ readiness to sail. The mutiny’s greatest impact was limited to a handful of ships as they lined up off the coast in Wilhelmshaven. Nevertheless, panicked by their subordinates’ disobedience, the naval command abandoned the operation during the night of 29-30 October. The men who led this mutiny were motivated by the desire to save themselves rather than risk their lives in a battle that they believed would have no impact on the war’s final outcome. After they had reassured their commanders of their loyalty, performing drills as instructed after the offensive operation had been abandoned, the III Flottilla, which included some of the most rebellious ships, docked in Kiel harbor. At this point in time several hundred sailors had been arrested for their role in the mutiny.

Early Protests and Escalation↑

On 1 and 2 November 1918, there were small protests in central Kiel. The participants’ motivations ranged from wanting to prevent any further offensive military operations to the goal of commencing a socialist revolution. However, the most important motivation at this point concerned the fate of their comrades arrested during the mutiny. Many of the protestors were mobilized by the memory of the repression of the previous year’s sailors’ protests and strike. That repression included investigations lead by officers that handed down harsh punishments to sailors, as well as the execution of the alleged strike leaders, Albin Köbis (1892-1917) and Max Reichpietsch (1894-1917). On 3 November, for the first time, several thousand sailors as well as a number of civilians participated in the protests. The protestors marched towards a military prison in central Kiel where some of the arrested men were held. When the protestors’ path was blocked by a combination of police and military during the ensuing confrontation, the soldiers opened fire, killing at least nine protestors and leaving many more wounded.

The Fall of Kiel↑

Enraged by the loss of life, the following day thousands more sailors joined the protests. Drawing upon the longer tradition of social unrest and political protest in Kiel during the First World War, including the food riots of June 1916, and the major strikes of March 1917 and January 1918, Kiel’s workers also declared a solidarity strike. At first, in the early morning of 4 November, the rebels appeared to be unsuccessful. However, by midday the protest had extended beyond the confines of central Kiel to include thousands of sailors in the military barracks at Wik, to the north of the city. The situation worsened for Kiel’s military commanders when soldiers sent from outside Kiel to reinforce their authority sided with the rebellious sailors. Faced with the escalation of the protests and unsure as to whether or not he possessed sufficient men willing to fire upon protestors, Admiral Wilhelm Souchon (1864-1946), the naval commander in Kiel, agreed to release the arrested men from the barracks and called upon the protestors to send a delegation to meet with him. On the evening of 4 November, Souchon, together with the Social Democrat Gustav Noske (1868-1946) and Conrad Haußmann (1857-1922), representatives of the Imperial government who had travelled to Kiel to investigate the previous day’s events, held a meeting with representatives of the protesting sailors. At this meeting the sailors drew up a list of fourteen points (echoing President Wilson’s fourteen points). The next morning, 5 November 1918, the red flag flew over the ships of the Imperial German Navy that remained in the harbour in Kiel, and the first revolutionary protests took place in the nearby coastal towns. On 6 November, the city of Hamburg, key to containing the revolution to the north of Germany, fell under the command of revolutionaries, and the revolution quickly spread across the rest of Germany.

Mark Jones, Freie Universität Berlin and University College Dublin

Reviewed by external referees on behalf of the General Editors

Selected Bibliography

- Dähnhardt, Dirk: Revolution in Kiel. Der Übergang vom Kaiserreich zur Weimarer Republik 1918/19, Neumünster 1978: K. Wachholtz.

- Deist, Wilhelm: Die Politik der Seekriegsleitung und die Rebellion der Flotte Ende Oktober 1918, in: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 14/4, 1966, pp. 341-368.

- Dittmann, Wilhelm: Die Marine-Justizmorde von 1917 und die Admirals-Rebellion von 1918, Berlin 1926: Dietz.

- Horn, Daniel: Mutiny on the high seas. The imperial German naval mutinies of World War One, London 1973: L. Frewin.

- Jones, Mark: Founding Weimar. Violence and the German Revolution of 1918-19, Cambridge 2016: Cambridge University Press.

- Jones, Mark: The crowd in the German November Revolution 1918, in: Weinhauer, Klaus / MacElligott, Anthony / Heinsohn, Kirsten (eds.): Germany 1916-1923. A revolution in context, Bielefeld 2015: Transcript, pp. 37-57.

- McElligott, Anthony: Rethinking the Weimar Republic. Authority and authoritarianism, 1916-1936, London 2013: Bloomsbury.

- Stumpf, Richard: Warum die Flotte zerbrach. Kriegstagebuch eines christlichen Arbeiters, Berlin 1927: J.H.W. Dietz.