The House of Morgan during World War I↑

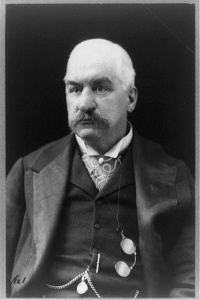

In the first decade of the 20th century, the “House of Morgan,” merchant bankers and brokers with offices in New York, London and Paris, reached the height of its powers after several firms were consolidated under the leadership of the legendary financier John Pierpont Morgan (1837-1913). These London and New York firms, which had connections to the Morgan family, had a long history of service to the British and U.S. governments. They had assisted with the financing of military activity such as the Boer War and acted to stabilize the U.S. economy in times of crisis (most notably during the U.S. Panic of 1907).[1] Although Morgan died in the spring of 1913, J. P. Morgan & Company continued to exert its vast influence when war began in Europe.[2]

During the period of American neutrality, the House of Morgan assisted the Allies in financing their war effort and helped the British acquire essential supplies in the American market. In addition to public activity, Morgan occasionally served British interests clandestinely. The House of Morgan foiled a plan by German investors to take over Bethlehem Steel by arranging for the company’s officers to put their shares in a voting trust to checkmate the German move.[3]

The War’s Effects on U.S. Commercial Relations↑

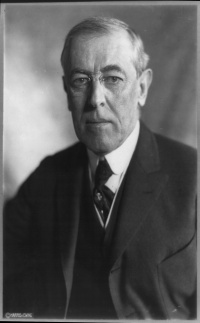

In the United States, the onset of war drove up the prices of war-related goods. At the same time, the international credit exchange was suspended and Federal Reserve policies interfered with the Allies’ ability to offer war bonds in the neutral United States. President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) pressed the Federal Reserve to warn American banks that a proposed Allied issue of short-term bonds in November 1916 would be a risky investment. The historian Robert Chernow speculates that Wilson wanted to use economic pressure to force peace negotiations.[4] No one had foreseen the length of the war or its voracious consumption of material resources. In spite of this, Americans needed to continue commercial relations with Europe; agricultural interests worried that without credit the Allies might not be able to purchase grain, meat, or cotton, while the Allies’ funds were rapidly dwindling. President Wilson, while struggling to devise a workable neutrality policy, was privately sympathetic to the Allies. He therefore accepted a suggestion by (Acting) Secretary of State Robert Lansing (1864-1928) that the United States permit “credits” for the purchase of American goods.[5] Henry Davison (1867-1922), one of the senior Morgan partners, said that “to maintain our prosperity we must finance it.”[6] The House of Morgan would perform a central role in facilitating the Allied war effort in spite of American neutrality.

Rescue of European-Owned NYC Bonds↑

One of the largest foreign obligations of the day, $80 million in New York City bonds held by British and French purchasers, was set to mature in 1915. These Allied creditors were desperate for cash to purchase war materials, but the city lacked sufficient funds to meet its obligation. J.P. Morgan & Company, in its traditional way, devised a solution for the problem. With the assistance of Kuhn, Loeb, & Co. they organized a consortium of about 125 banks to cover the city’s debt. By underwriting a $100 million bond issue, they were able to send $80 million in gold to the money-starved Europeans, who would most likely spend these funds in the United States.[7]

American Foreign Securities Company↑

In another instance of working around potential difficulties, Morgan organized the American Foreign Securities Company, which raised $100 million for the French government by selling three-year 5 percent gold notes. The French provided collateral of $20 million worth of securities to AFSC and guaranteed to keep this bundle of securities at a value 20 percent above the amount of the loan. Several arrangements such as these – an American offering of securities backed by various forms of Allied collateral – substituted these American transactions for a more straightforward issuance of war bonds that was impossible in the neutral United States’ market.[8]

Purchasing Agent for the British↑

However they secured the funds, early Allied spending in the U.S. was chaotic. Desperate for supplies, the Allies, and on occasion departments within a particular country, bid against one another and drove up the prices of American goods. Henry Davison proposed that if the Allies could make their purchases through a single agency the bidding wars would end. In December 1914 at a meeting with Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith (1852-1928) and Chancellor David Lloyd George (1863-1945), Davison presented a proposal to make Morgan a purchasing agency for the British. The British Army Council and the Admiralty signed the Commercial Agreement contract with J. P. Morgan & Company in January 1915. The arrangement was not exclusive, but Morgan handled most of the purchases. Although the U.S. administration had blocked the sale of war bonds by belligerents, in late January President Wilson gave J. P. Morgan, Jr. (1867-1943) his quiet approval for any action “in furtherance of trade.”[9] Later in the spring a similar agreement was completed with the French government.[10]

To manage British purchases J.P. Morgan & Company added an Export Department under Edward R. Stettinius, Sr. (1865-1925), the president of the Diamond Match Company. At the peak of activity, Stettinius’ group bought, insured, and shipped as much as $10 million of goods per day, everything from corned beef to locomotives. When some American resources were strained by the demand, Stettinius called for more factories. The House of Morgan and the British government advanced money to firms to assist them in making improvements or expansions necessary to meet the demand. Stettinius’ activity, which represented about half of all Allied purchases during the period, totaled $3 billion. Thus, the house of Morgan’s 1 percent commission amounted to $30 million.

House of Morgan’s Role Ends↑

After the United States declared war, these elaborate efforts no longer were needed and the House of Morgan returned to the concerns of the pre-war years when it had been one of the targets of advocates for tightened regulation of banking and finance. The great J. P. Morgan himself had been called before a 1912 Congressional committee to explain his banking practices. Even the Morgan activity on behalf of the Allies became ammunition for some enemies who accused it of war profiteering. The passage of the Clayton Antitrust Act and the Sixteenth Amendment (income tax) heralded the arrival of a new business environment, inhospitable to the old financial giants. To adapt to these changes, J. P. Morgan & Company divided into separate banking and brokerage firms. The House of Morgan never again took such a prominent role in the affairs of nations as it had in World War I.[11]

Kathryn Kemp, Clayton State University

Section Editor: Lon Strauss

Notes

- ↑ Wicker, Elmus: Banking Panics of the Gilded Age, New York 2000, pp. 84-96; Strouse, Jean: “Chapter 28, Panic,” in: Morgan. American Financier. Kindle edition, New York 1999.

- ↑ Markham, Jerry W.: A Financial History of the United States. From J. P. Morgan to the Institutional Investor (1900-1970), Vol. II, Armonk 2002, pp. 31-34; Satterlee, Herbert L.: J. Pierpont Morgan, An Intimate Portrait, New York 1939, details Pierpont Morgan’s role in the House of Morgan as remembered by his son-in-law; Strouse, Morgan 1999, also provides a useful acount of his career; Chernow, Ron: The House of Morgan, an American Banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance. Kindle edition. New York 1990, focuses on the history of the firms that ultimately made up the House of Morgan, including J. S. Morgan & Co. (London); Drexel, Morgan & Co. (New York); and Morgan, Harjes (Paris).

- ↑ Chernow, The House of Morgan 1990, Kindle location 3765.

- ↑ Markham, A Financial History 2002, p. 72.

- ↑ Chernow, The House of Morgan 1990, Kindle locations 3707-3712.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Markham, A Financial History 2002, pp. 70-71.

- ↑ Ibid, pp. 72-73 discusses this and several similar arrangements. “American Foreign Securities Company [advertisement],” United States Investor. (July 23,1916): 7, is the AFS announcement of the $100 million loan.

- ↑ Chernow, The House of Morgan 1990 (Kindle pp. 3742-3744). Wilson pressed the Federal Reserve to warn American banks that a proposed Allied issue of short-term bonds in November 1916 would be a risky investment; Chernow speculates that he wanted to use economic pressure to force peace negotiations.

- ↑ Ibid, Kindle Locations 3722-3735; Markham, A Financial History 2002, p. 72.

- ↑ Markham, A Financial History 2002, pp. 168-169.

Selected Bibliography

- Chernow, Ron: The house of Morgan. An American banking dynasty and the rise of modern finance, New York 1990: Atlantic Monthly Press.

- Markham, Jerry W.: From J.P. Morgan to the institutional investor (1900-1970), volume 2, Armonk 2002: M. E. Sharpe.

- Satterlee, Herbert Livingston: J. Pierpont Morgan. An intimate portrait, New York 1939: Macmillan.

- Strouse, Jean: Morgan. American financier, New York 1999: Random House.

- Wicker, Elmus: Banking panics of the Gilded Age, Cambridge; New York 2000: Cambridge University Press.