Origin and Different Names↑

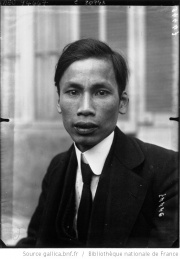

The man known as Hồ Chí Minh (1890-1969) was born in Nghê An, a province in central Vietnam. According to Vietnamese custom, his birth name was Nguyễn Sinh Cung. He was renamed Nguyễn Tất Thành when he was ten years old. Throughout his life, he used 165 pseudonyms (pennames and clandestine aliases).

France colonised Việt Nam from the late 1850s through the 1880s. The last military resistance, Cân Vương (the “For the King” movement), surrendered in 1897. The French divided Việt Nam into three administrative entities from south to north in order to rule it more easily: Cochinchina (south) was a colony, while Annam (centre) and Tonkin (north) were two protectorates formally ruled by a Vietnamese emperor but controlled by French résident supérieurs. The three names were not neutral: Tonkin and Cochinchina had been used by Catholic missionaries who had been present in Vietnam since the 1600s, while Annam came from Chinese, meaning “pacified south”, thus framing France as an heir to the Chinese suzerain.

Tây Du/Go West↑

Hồ Chí Minh left his home province at the age of nineteen, after his father, a mandarin who served as a district chief, was penalized for abuse of power, dismissed and fell into destitution. However, unlike other young nationalists, he did not join the youth recruited by the revolutionary Phan Bội Châu (1867-1940) to Đông Du (Go East). They attended schools in Japan, where Phan Bội Châu lived in exile, until the Japanese government expelled them after it was granted a loan from a French banking corporation in 1908.

With a thought for Confucius’ (ca. 551-479 BC) saying, “across four seas, all men are brothers”, Hồ Chí Minh chose seafaring, working as a cook or a steward on French cargo liners to Tây Du (Go West). According to official histories, he wished to enjoy true liberté, égalité et fraternité, a revolutionary slogan that the colonialist government infringed upon every day in Vietnam.[1] Simultaneously, he aimed to create a network of personal and collective supporters for the cause of Vietnamese independence.

Hồ’s exclusive goal was recovering the independence of his country. Therefore, when he worked in London at the Carlton Palace hotel, according to his 1948 autobiography, he cried when he heard about the Irish mayor of Cork, who was jailed by the British and died after a 74-day hunger strike. Hồ said that the incident made him realise that Europeans could also experience colonial domination and that the struggle for independence was not a Vietnamese exception. Hence, international solidarity became an issue in his strategy.

When war broke out in 1914, Hồ wrote a postcard to Phan Châu Trinh (1872-1926), who lived in Paris and was the leader of the Vietnamese modernisation movement that relied on the French government for reforming the colonial regime in line with enlightenment philosophy and the principles of the 1789 revolution:

These words suggest that Hồ thought that the colonized people of Asia could eventually benefit from the exhaustion of the imperialist powers fighting each other.

In 1916 and 1917, two uprisings broke out in Vietnam. In the imperial capital of Hué, in central Vietnam, the young Emperor Duy Tân (1900-1945), who had acceded to the throne in 1907, was implicated in an insurrection. In Thái Nguyễn, a northern province, political prisoners mutinied and resisted the French for more than a month. Both upheavals were defeated, but for Nguyễn Tất Thành and Hồ Chí Minh, these incidents provided strong signals in favour of seizing the opportunity to press the French government to reform the colonial regime. According to what he reported several years later to the Russian newspaper Pravda, Hồ crossed the English Channel in 1917, in hope of spreading nationalist propaganda among the 49,180 Indochinese workers and 42,922 soldiers in France.[3] However, by 1919, most had been repatriated.

In that year, Hồ first used the name “Nguyễn Aí Quốc”, and the French government searched for whoever was hiding behind that pseudonym. He was shadowed every day and two informers approached the group called the Five Dragons.[4] The French authorities were, thus, able to identify him.[5] However, he was neither harassed nor arrested. Indeed, in 1921, he was invited to talk with Albert Sarraut (1872-1962), minister of colonies, to whom he dared assert that the Vietnamese wanted their independence.

1919, a Turning Point↑

When he arrived in Paris, Thành joined Phan Châu Trinh and stayed in the apartment that Phan Văn Trường (1876-1933) rented, where several Vietnamese found accommodation and gathered to debate domestic and international affairs. At that time France was a theatre of social turmoil, stricken by the death of more than 1 million, with hundreds of thousands wounded. Material losses had hit not only industrial centres but also the agricultural areas. The soldiers, workers, and bourgeois from the colonies, who expected a reward for their “sacrifices”, were not satisfied with their post-war lot and the Five Dragons voiced their frustration through newspapers, public speeches, and letters to French governors.

Hồ Chí Minh also attended scientific, technical, and art exhibitions. He met with foreigners, including Chinese, Korean exiles, Japanese, supporters of Irish independence, French leftists, and members of the Ligue des droits de l’homme (League of Human Rights). He participated in forums (Le Club du Faubourg), where he could improve his French and make statements on colonialist oppression.[6] He wrote articles for newspapers, such as the Socialist party and later Communist L’Humanité, the trade unionist La Voix ouvrière, and even, on one occasion, the anarchist Le Libertaire. He also toured Italy and Switzerland through the left association Tourisme et Travail.

His daily life was not only devoted to political activism. To earn a living, Hô was trained in photography retouching by Khánh Ký (1874-1946).[7] His work retouching photos not only contributed to rumours of Hô’s romance with a young French demoiselle but also allowed him to contribute to personal and collective needs. The apartment rented by Phan Văn Trương was not only a place of casual encounter but also a communitarian haven sustained by migrants’ mutual aid.

In 1921, political disagreements inside the Five Dragons circle drove Hô to rent a room in a working-class precinct, north of Paris. Spartan life superseded relative comfort: his small room was without electric light, heating, and running water. Moreover, his diet was poor and Hô’s later tuberculosis has been attributed to this period of his life.

Hô seized the opportunity to move toward the forefront of political activism when he went to the Peace Conference in Versailles. He had drafted a petition entitled Demands of the Annamite People (dated 18 June 1919) that was inspired by Phan Châu Trinh, written down by Phan Văn Trường and signed “Nguyễn Aí Quốc.” Though this signature was a collective name for those presenting the petition, Hô kept it exclusively for himself until 1942.[8] He expected to hand the petition to President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) in person, but he was disappointed when Colonel Edward House (1858-1938) politely said that he would pass on the message to the United States president. Hô was made aware that the great powers decided the destiny of the smaller powers. This event was surely a milestone in his political radicalisation.

Radicalisation, Go East↑

A decisive step was taken by the French leftist movement in December 1920, during the 18th congress of the French Socialist party, where the key issue debated was whether or not to join the Third International founded by Vladimir Lenin (1870-1924) in 1918 after the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia. Hô joined the French Socialist party in 1919. Along with the majority of delegates, he voted for adhesion to the Third International.

In so doing, he confirmed the divergence of political opinions and projects among Phan Châu Trinh’s circle. He often said, “We have to make noise” (meaning “revolution”), as the French Socialist party did not much concern itself much with colonial issues. Reform was too slow a process for Hô, as “we cannot wait anymore”.[9] At the Tours Congress at which the Communist party was established in 1920, he greeted Lenin’s call for the Third International to give priority to anti-colonial struggle with much enthusiasm.

Hence, Hồ Chí Minh, under the name of Nguyễn Aí Quốc, joined the new French Communist party’s committee for colonial affairs and participated actively in anti-colonialist propaganda: he was the main (but not sole) editor of the journal Le Paria, published by the Union intercoloniale.[10] He also wrote Le Dragon de bambou, a satirical play which caricatured Emperor Khái Đinh (1885-1925) as a puppet of the French; the play was staged during a festival of the Communist newspaper L’Humanité.

Although Hô’s old mentor Phan Châu Trinh realized that the French would neither reform nor abolish the colonial regime, he continued to support a non-violent strategy through cultural change (such modern rationalist and scientific education, and boosting the quốc ngử popular press[11]). Phan did not agree with Hô, but he nevertheless told him to “go home to accomplish your project, in France you waste your time”. Hồ Chí Minh, who increasingly criticised the French Communist party for not intensifying its anti-colonialist activities, secretly left France for Moscow in 1923. His hope of meeting Lenin was not fulfilled because Lenin was very ill and died on 21 January 1924.

Pierre Brocheux, University Paris Diderot

Section Editors: Jan Schmidt; Sōchi Naraoka

Notes

- ↑ Nguyen, Ai Quôc: Le procès de la colonisation française, Paris 1925.

- ↑ Letter dated 1914, signed Paul That Thanh and intercepted by French police, in Archives nationales d’Outre-mer, fonds Service de liaison des originaires des territoires français d’Outre-mer III.29. Hereafter: ANOM, fonds SLOTFHOM. Five letters sent from London in 1913 and 1914 were intercepted by French censorship.

- ↑ Vu-Hill, Kimloan: Coolies into Rebels. Impact of World War I on French Indochina, Paris 2011. This author referred to French state archives.

- ↑ The Five Dragons were Phan Châu Trinh, Phan Văn Trường, Nguyễn Thế Truyền, Nguyễn Tất Thành and Nguyễn An Ninh.

- ↑ French National Archives in Aix-en-Provence, fonds Indo SPCE365; fonds F07-13405 file 306.

- ↑ Karnow, Stanley: This Tiny Annamite, in: Paris in the Fifties, New York 1997. The Club du Faubourg was a leftist but popular free place of debate on a large range of subjects.

- ↑ Khánh Ký (1874-1946) is the reputed founder of modern photography techniques and art in Vietnam during the colonial period. He was ranked higher than the French photographers.

- ↑ Hô Chi Minh admitted that “Yet I cannot write French” and that “Phan Văn Truong was the true author of Demands of the Annamite People”, in: Trần Dân Tiến: Những mậu chuyện, Hanoi 1984, pp. 32-35. The Demands can be found in Ho, Chi Minh: Selected Writings, Hanoi 1977, pp. 22-23. The demands were moderate. They did not claim independence but wished to enjoy the same rights as French citizens.

- ↑ French National Archives, see note 5.

- ↑ L’Union intercoloniale, created by the French Communist party, gathered Indochinese, Malagasy, Antillais and Africans together. Le Paria (The Outcast), published from 1922 to 1936, was a polemical and satirical paper.

- ↑ In the 16th century, the Jesuit missionaries transcribed the Viet language using the Latin alphabet, thus facilitating evangelization. Later, in the 19th century, the French colonial government generalized the writing system, which avoids the learning of Chinese ideograms, through education and media. It was a tool for mass education that the Viet reformers/modernisers adopted and so “reversed the weapon”.

Selected Bibliography

- Brocheux, Pierre: Ho Chi Minh. A biography, Cambridge 2007: Cambridge University Press.

- Duiker, William J.: Ho Chi Minh. A life, New York; London 2000: Hyperion.

- Gaspard, Thu Trang: Hô Chí Minh à Paris (1917-1923), Paris 1992: Harmattan.

- Goebel, Michael: Anti-imperial metropolis. Interwar Paris and the seeds of Third-World nationalism, Cambridge 2015: Cambridge University Press.

- Quinn-Judge, Sophie: Ho Chi Minh. The missing years, 1919-1941, Berkeley 2002: University of California Press.