Pre-war Career↑

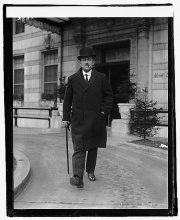

Before 1914, Maurice Hankey (1877-1963), a former Royal Marines artillery officer, was secretary of Britain’s Committee of Imperial Defence. He was responsible for preparing the War Book that government departments would implement when hostilities commenced.[1] He used his administrative skill to manage the adaptation of peacetime government procedures to the requirements of mass warfare.

Modifying the Machinery of Government↑

By the end of 1914 the ad hoc peacetime practices of British cabinet government were adapting to the demands of managing an expanding coalition war day-by-day. By November a small War Council had been set up along the lines of the pre-war Committee of Imperial Defence, comprised of civilian ministers and service chiefs of staff, to direct strategy and determine war policy. Hankey was its secretary and for the first time formal minutes of ministerial discussions and decisions were kept. Although tactful and dry in his record taking, Hankey’s minutes grant an insight into the managerial complexities and personal disagreements of wartime policy-making. Hankey retained his secretarial function as the War Council adapted (as much through shifts in wartime political alignments as in response to the growing demands of war management), becoming the Dardanelles Committee in May 1915, the War Committee in January 1916 and finally a small executive War Cabinet after David Lloyd George (1863-1945) came to power in December 1916. A man capable of sustaining a prodigious workload, Hankey also headed the Cabinet Secretariat established at the same time and was to be secretary of the Imperial War Cabinet created in 1917.

A conciliator as well as a facilitator, Hankey frequently acted as the conduit between the War Cabinet and government ministers or as a peacemaker in times of civil-military disagreement. “The cement that bound all Cabinet’s together” in Asquith’s estimation,[2] Hankey’s administrative talents meant that he remained invaluable and necessary to ministers and the senior soldiers and sailors with whom they ran the war. “He discharged his very delicate and difficult function with such care, tact and fairness that I cannot recall any dispute ever arising as to the accuracy of his Minutes or his reports on the actions taken,” Lloyd George later attested.[3]

Hankey was also secretary to many of the inter-allied conferences that managed the wartime coalition. He pressed for a structure similar to the British war organisation with an inter-allied secretariat to manage wartime alliance affairs but he did so without success until a Supreme War Council was created in November 1917.[4]

Strategy in Wartime↑

Hankey’s central position in the machinery of government naturally gave him privileged insights into strategy and politics and he became a trusted adviser to successive wartime Prime Ministers Herbert Henry Asquith (1852-1928) and Lloyd George. His “Boxing Day memorandum” in 1914 was among the outpouring of War Council members’ papers that argued for focusing British strategy away from the stalemated western front towards the Balkans and Middle East which led to the mismanaged Dardanelles expedition. His contention that “Germany can perhaps be struck most effectively and with the most lasting results on the peace of the world through her allies, and particularly through Turkey” was enticing in December 1914, but a distraction from the real centre of gravity of the war against the Central Powers.[5] As a former Royal Marine, Hankey was always an advocate of a maritime strategy – his memorandum also advocated economic warfare and occupying German colonies, strategies from the pre-industrial age – rather than one that concentrated British effort on the costly attritional war being waged to defeat the German Army on the western front – in which his brother Donald Hankey (1884-1916) was to be killed. Such a perspective naturally endeared him to Lloyd George who shared his concerns about the army’s mounting losses in France and the new Prime Minster increasingly turned to Hankey for alternative strategic advice to that proffered by his “westerner” military advisers. Hankey certainly influenced the decision to adopt a convoy system to protect merchant shipping from U-boats during the second German unrestricted submarine warfare campaign in 1917, arguing the case to a reluctant Admiralty.[6] Yet although his views aligned with Lloyd George’s thinking about wartime strategy, it is improbable that they steered the Prime Minister into new directions that he had not already chosen for himself.

Post-war Career↑

Justly recognised as the originator of modern civil service practices, Hankey was knighted for his war service in 1916. After hostilities ended he served as secretary to the British delegation and then to the Council of Four at the peace conference in Paris. He remained the first British Cabinet Secretary until his retirement in 1938, in which role he was responsible for creating the modern Cabinet Office as the center of governmental administration. In this role he was responsible for vetting the many political memoirs published after the war. On retirement he was ennobled as Baron Hankey. He was a minister in Neville Chamberlain’s (1869-1940) and Winston Churchill’s (1874-1965) early Second World War administrations. He left an important memoir of his own, The Supreme Command, which outlined the evolution of wartime administration as well as strategic disagreements between statesmen and soldiers, based on a detailed, unpublished, wartime diary.

William Philpott, King's College London

Section Editor: Jenny Macleod

Notes

- ↑ D’Ombrain, Nicholas: War Machinery and High Policy, Oxford 1973, pp. 264-265.

- ↑ Spears, Louis: Prelude to Victory, London 1939, p. 137.

- ↑ Lloyd George, David: War Memoirs, 2 volumes, London 1938 edition, p. 643.

- ↑ Philpott, William: Squaring the Circle. The Higher Co-ordination of the Entente in the Winter of 1915-16, in: The English Historical Review CXIV/458 (1999), pp. 875-898.

- ↑ Memorandum by Hankey, 28 December 1914 in Gilbert, Martin (ed.): Winston S. Churchill, 1914-16. Vol. III: Companion, part 2: May 1915-December 1916, London 1972, pp. 337-43.

- ↑ Hankey, Maurice: The Supreme Command, 1914-1918, volume 2, London 1963, pp. 641-51.

Selected Bibliography

- Hankey, Maurice Pascal Alers: The Supreme Command, 1914-1918, London 1961: Allen & Unwin.

- Roskill, Stephen Wentworth: Hankey. Man of secrets, 1931-1963, volume 3, London 1974: Collins.

- Roskill, Stephen Wentworth: Hankey. Man of secrets, 1877-1918, volume 1, London 1970: Collins.

- Roskill, Stephen Wentworth: Hankey. Man of secrets, 1919-1931, volume 2, London 1972: Collins.