Introduction↑

The study of pictorial war publicity and propaganda in the print media has been largely restricted to authorial and stylistic histories of the poster and graphic design.[1] There are many studies focussing on the war poster beginning with those of Martin Hardie and Arthur K. Sabin (1920).[2] These early studies were important for the self-understanding of the graphic artist and the status of the commercial arts which was often positioned as a subcategory of art and in an international context.[3] Large-scale propaganda efforts carried out by the belligerents were also documented in many firsthand accounts from participants in the war[4] and by historians of propaganda. These reports generally lacked a specific and detailed analysis of the role of the print media industry and the advertising trade.[5]

Later studies such as Jeremy Aynsley’s (2000) excellent history of German graphic design take account of the issues residing in the structures of production and consumption of commercial art. However, few authors apart from Stephen L. Vaughn (1980), Nicholas Hiley[6] and Jim Aulich and John Hewitt (2007) have attempted to draw out the connections between government propaganda and the advertising industry or to investigate the wider discursive and rhetorical contexts of print media. Most histories of advertising tend to make short work of the 1914-1918 period and underestimate the political importance of the war for the advertising industry, government and the public.[7] In recent years, Allen J. Frantzen (2004), Celia Kingsbury (2010) and Gabriel Koureas (2007) have taken gendered approaches to analyzing the symbolism and mythology of the official rhetoric of war aims. In addition, Pearl James’ (2009) edited collection of essays addresses many of the major issues such as gender, national identity and questions of modernity within a wider transnational visual cultural approach.

The need to maintain morale at home and at the front and to generate interest in war savings, loans and bonds, salvage, war work, food and fuel conservation through propaganda campaigns was common to all belligerents. To varying degrees, war aims were also used to sell the war and the war was used to sell consumer products. The Central Powers were more sophisticated in terms of design philosophy but the graphic articulation of war aims. Allied rhetoric was more commercially and psychologically aware, focussed more closely on the positive representation of contemporary civilian and military social orders and was ultimately more effective in the manipulation of public opinion.

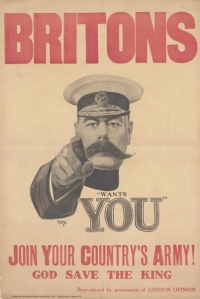

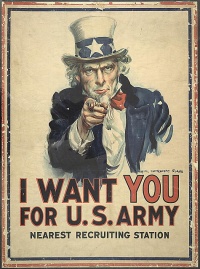

Alfred Leete’s (1882-1933) design for the poster ‘BRITONS’ featuring the lithographic portrait image of Horatio Herbert Kitchener (1850-1916) is possibly the best-known war poster of all time. The single image and bold lettering addresses the viewer directly in a pattern repeated by poster designers in Germany, Russia, America and Italy. Issued by a magazine, it is also a vital piece for the understanding of the production of visual propaganda because it signalled the incorporation of the rhetoric of government propaganda and public information with advertising and publicity.

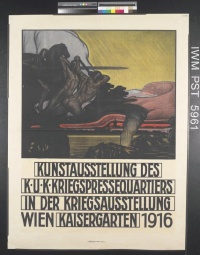

Governments commissioned printing houses and advertising agencies to propagandise war aims and influence public opinion at home and abroad. Many British designs were distributed throughout the Empire, for example, and in just over eighteen months America produced 20 million posters, more than all the other belligerents put together. Designs appeared in various guises as posters, postcards, display advertisements, window cards, on billboards and hoardings, and in one-off large-scale installations and exhibitions. Together they promoted war aims, products, rallies, events, lectures, fund-raising exhibitions and benefit concerts in publicity campaigns.

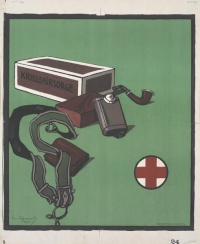

The use of patriotic imagery by voluntary organisations, charities, and commercial enterprises such as banks, publishers, filmmakers, entertainments and manufacturers of consumer goods reproduced and fed back into official campaigns. The YMCA, Church Army and the International Red Cross effectively functioned as branches of government: a German Red Cross postcard, for example, displayed the German nation personified as a medieval knight who heralds a column of troops over the caption “Deutschland über alles.”

Print technologies were fairly equally distributed among the combatants and all could produce large print runs of full colour posters relatively cheaply and efficiently. Employed by government and commerce, graphic artists worked in a complex state of affairs defined by rules of censorship and “respectability.” Campaigns were rarely subject to overall strategies and were reliant on local responses of varying sophistication from printing houses, anonymous artisans and internationally known artists. They utilised the stock poster, typographical proclamation, letterpress, and patriotic or commercial imagery in a variety of styles. The relative evolution of the communication industries and the debates concerning design education and practice were equally important. The more psychologically astute iconography found in Britain and America, contrasted with a design philosophy in the Central Powers which considered the material and aesthetic implications of mass production for the print media. Simultaneously, graphic designers were subject to pressures from military authorities to articulate nationalist myths of sacrifice, the iron and steel of the forge, the sword and the plough. Anglo-American practices of design concentrated on good business, marketing and efficient communication where aesthetic experiment might be considered to have value as art, but not as communication.

The Patriotic Poster and War Aims↑

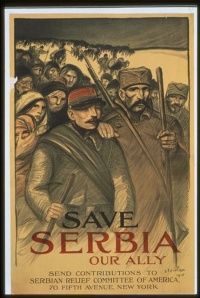

All combatant countries produced what British contemporaries called the “patriotic poster.” The national rhetoric may have differed in substance and affect, but the issues at play were similar. The war created its own calendar days dedicated to fags, flags, France, liberated regions, poilus (French infantrymen), sacrifice, tanks, Serbia, events such as the exhibition of war trophies or art and benefits supporting refugees, prisoners, the disabled and the blind. National flags were raised: eagles flew for Austria, Germany and America; cockerels and lions strutted for France and the British Empire. Historical heroes such as Horatio Nelson, Lord Nelson (1758-1805), Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington (1769-1852) and popular contemporary figures such as Nurse Edith Cavell (1865-1915), President Paul von Hindenburg (1847-1934), Max Immelmann (1890-1916), Lord Kitchener and General Erich Ludendorff (1865-1937) stood alongside the allegorical figures of Britannia, Germania, Colombia, Italia Turrita and Marianne. St. George slaughtered dragons for Britain, Austria and Russia. Female personifications of liberty, plenty, victory and peace mingled with John Bull and Uncle Sam and a menagerie of serpents, monsters and demons. The coin of the realm was deployed offensively for the Allies and defensively for the Central Powers. Swords were drawn and cannons thundered, soldiers charged, aeroplanes wheeled, war workers laboured. Skies threatened, sunsets mourned the passing of the day and sunrises held the promise of peace.

Governments wanted to reach as wide an audience as possible and artists did not confine their vocabularies to the cartoonist’s armoury. An important factor in unifying a people against an enemy is fear. Atrocity propaganda gave both true and false publicity to acts of violence carried out against civilians or unarmed prisoners. Early in the war, Germany influenced opinion at home and in neutral countries by publicising the negative effects of the British naval blockade on civilians. However, incidents such as the sinking of the Lusitania, the execution of Nurse Cavell, the destruction of the Reims cathedral and unrestricted submarine warfare were widely propagandised in the graphic media as evidence of German barbarism. In Britain, fear of aerial attack fed on already existing pre-war discourses in fiction, illustration and reporting, especially in the Northcliffe press.[8] In German and Austro-Hungarian posters, the aeroplane and the submarine were chariots of the air and sea piloted by heroes. In Britain and to a lesser extent America, technological advantage in war was often presented as treacherous. The satirical poster, “Knights of the Air. My German Heroes!” by Howard van Dusen (1868-1948) has German aircraft attack the Red Cross; Joseph Pennell’s (1857-1926) “That Liberty Shall Not Perish From the Earth,” 1918, has bombers fly over a blazing New York.

In May 1915, Charles Masterman’s (1873-1927) British War Propaganda Bureau published the Bryce Report in thirty languages.[9] In an effort to demonise the Central Powers, it gave credibility to reports of German atrocities in occupied Belgium and controversially influenced America to join in the war. Widely found in press reports and folios of cartoons and photographs, atrocity imagery was unusual in posters because the trade was self-regulated and avoided displaying lurid subject matter in public space. A few British posters made explicit or implicit reference to the rape and slaughter of civilians such as “Is Your Home Worth Fighting For”[10] and “Remember Belgium.”[11] The War Savings Committee thought that Frank Brangwyn’s (1867-1956) poster “Put Strength in The Final Blow,” 1918, was too extreme and was cited by the Germans as an example of British barbarism. Right-wing nationalist groups such as the British Empire Union did produce sensationalist posters. David Wilson’s (1873-1935) “Once a German - Always A German!”[12] was distributed for sale in France, Belgium and Britain: the enemy bayonets babies, murders nurses, burns cathedrals and sinks merchantmen. The Central Powers generally avoided this demonizing strategy and was restricted to warning the population of the dire consequences of defeat in images of starvation and, towards the end of the war, the spectre of Bolshevism. In France, a poster advertising an album of war illustrations L’Almanach Vermot 1917 under the strap “Saluez!!! C’est Verdun!” showed mountains of dead and was licensed by the Paris censor’s office for indoor display only. References to atrocity in official Allied posters such as "A Reminder from France," 1917, published by the Department of Information were more likely to be written, rather than visual, requiring a studied rather than glancing response. Atrocities often found visual expression in places far from the fighting, such as the British colonies of South Africa or Australia where Norman Lindsay’s (1879-1969) posters focussed on the brutality of the fighting and most famously in Fernando Amorsolo’s (1892-1972) poster for War Bonds of a crucified Canadian soldier published in Manila by the Bureau of Printing.[13]

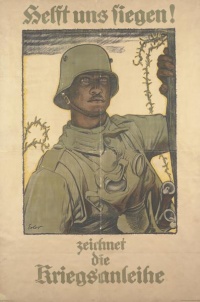

Humour can also be found in wartime propaganda posters. Bert Thomas’ (1883-1966) Tommy uttered “Arf a mo, Kaiser” while he lights his pipe, Bruce Bairnsfather’s (1887-1959) Old Bill found a ‘better ‘ole’ to go to,[14] and the poilu swigged on his bottle of wine. The soldier from the Central powers always more serious and existential, stood alone on mountain tops stared meaningfully into the future. The stark realism of the lithographic drawing of Frank Brangwyn in Britain, Theophile Steinlen (1859-1923) in France, Fritz Erler (1868-1940) and Lina von Schauroth (1874-1970) in Germany and Ivan Vladimirov (1869-1947) in Russia, contrasted with the more open and lighter lithographic realism of Gerrit A. Beneker (1882-1934) in America.

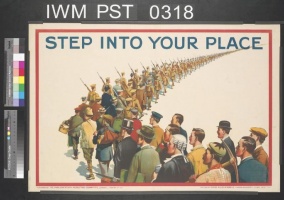

In Britain and later America, the message of wartime posters was characterised by calls for freedom, democracy, individual liberty and national self-determination. In President Woodrow Wilson’s (1856-1924) words, it was “a war for democracy, a war to end war, a war to protect liberalism, a war against militarism, a war to redeem barbarous Europe, a crusade.” (This message was tinged with an irony not lost on the men conscripted to the front, especially colonial troops.[15]) To help ensure total commitment, image-makers in Britain and America recognised the need to reach little-represented sections of the community and depict them in nationally defined roles. Encouraged by the involvement of specialists from the publicity industry, government and commerce employed the rhetoric of marketing to create the image of a new modern aspirant working and professional middle class: scientific, progressive, hygienic, efficient and socially mobile.

Allied iconography brought the nation together in its military, industrial, agricultural and domestic work as Pearl James has pointed out.[16] Civilians literally join hands with the military and the services with each other. Working people in Britain, Russia, France and America drew identity from the national cause which often encompassed non-traditional roles: the woman in industry and the working class man giving his labour to the national cause. Particular types of citizens were made visible as consumers which encouraged new forms of representational enfranchisement, legitimised in publicity sponsored by government and commerce.

The first substantial advertising campaign of the war was conducted by the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee (PRC) in Britain. It applied multiple modes of address including a high proportion of typographical posters as well as traditional appeals to King and Country. Lithographic techniques emulated the look of photography rather than the pencil or the brush and placed men in clean uniforms next to civilians or in desirable contemporary domestic interiors. These techniques can be seen the emotionally loaded “Daddy, What Did YOU Do In the Great War?” 1915. Metropolitan men were encouraged to fight, often by mothers and children for the greater family of the nation. Campaigns were generally positive in tone and even bread rationing was framed in terms of sinking U-boats. Posters exploited the most up-to-date marketing techniques using simple non-narrative imagery and slogans such as “If The Cap Fits YOU, Join the Amy Today,” 1915, or “Which [Hat] Ought You to Wear?” 1915, and “Step Into Your Place” where direct modes of address implicate the reader in larger questions of social responsibility framed by the “look” of a progressive and enlightened country.

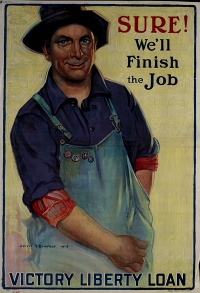

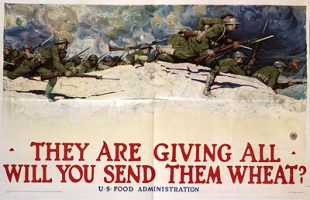

The situation in America was comparable. The Committee for Public Information (CPI) was in charge of government publicity under the directorship of George Creel (1876-1953) the populist former newspaperman and associate of President Wilson. Led by the commercial illustrator Charles Dana Gibson (1867-1944) who engaged prominent illustrators to work voluntarily, the Division of Pictorial Publicity produced some 700 designs for posters for the draft, war production, bonds and savings (though it is important not to underestimate the role of other government departments, corporations, charities and initiatives such as poster competitions in the production of designs).[17] Campaigns were aggressively exuberant and overwhelmingly illustrative in style. August Hutaf’s (1874-1942) “Treat ‘em Rough! Join the Tanks,” 1918, for the Tank Corps took a cartoonist’s approach complemented by Harvey Dunn’s (1884-1952) painterly full colour lithographic rendition of battle “They Are Giving All,” 1918, for the US Food Administration. The most widely distributed poster of the war, Beneker’s “Sure! We’ll Finish the Job” for the Victory Liberty Loan was permeated with a sense of easy pragmatism. In James Montgomery Flagg’s (1877-1960) “Tell that to the Marines,” 1918, the white collar worker literally gets down to business. Uniquely, as if to emphasise the closeness of commerce and government, Howard Chandler Christy's (1873-1952) highly popular posters for the Navy made use of marketing techniques based on psychological appeals to the fulfilment of desire and immersed official rhetoric in suggestive images of available young women. Historians have also noted how the iconography of buddies found in Flagg’s “Together We’ll Win,” 1918 frequently spilled over into the homoerotic and the phallic. The relationships between man and machine in American posters found expression in the imagery of cannon and shell; and in German posters the relationship between man and myth was found in the imagery of the sword and the naked warrior.

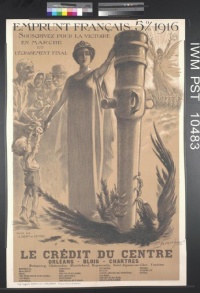

Under the constraints of military censorship, the political truce known as l’Union Sacrée (the Sacred Union) in France defined the political and social alliance necessitated by the German invasion. Iconographically, figures of Marianne, the poilu, the bourgeoisie and the peasantry obscured political and class differences in the name of the republic and liberty. Down-to-earth, democratised and humanised pictures of the soldier’s lot as father, lover and, in the case of advertising posters, drinker, were abundant. The imagery extended to the allegorical in a battle of symbols similar to cartoons by Will Dyson (1880-1938) in Britain and Louis Raemaekers (1869-1956) internationally. Ranging from the sublime to the ridiculous French campaigns did little to convince: the German imperial eagle was slaughtered by a French soldier naked except for a helmet and the tricolour in a poster by Jules Abel Faivre (1867-1945); in another by H. Falter, a poilu throttled the same emblem of German strength like a farmyard chicken. Others, such as Charles D. Fouqueray (1869-1956) drew heroic representations of the fighting in a romantic vein discordant with the savagery of the subjects portrayed. Concerns were also focussed on questions of aesthetic quality but not from the point of view graphic design. Many of its best-known poster artists were academicians of the first rank and their posters emulated the artist’s lithograph.

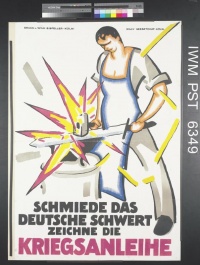

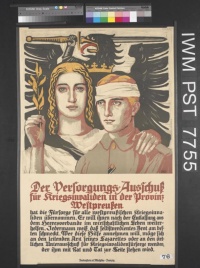

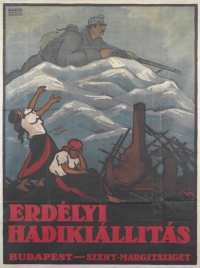

Burgfrieden, literally “Fortress Peace”, was the name of the German political truce inspired by the war. It defined the nation by ethnicity and a sense of historical destiny. Produced under military censorship, posters featured grave lithographic drawings of war workers in factory and field, soldiers in action, lone border guards, the disabled and prisoners of war to create an image of a beleaguered homeland. The people were seen, and saw themselves, as victims and passive subjects. At the same time, images of medieval knights, naked warriors and eternal flames articulated a transcendent German Kultur expressive of a pan-German community dependent on atavistic myths of heroism, ritual, sacrifice, blood, iron and soil. The promise was for the ultimate, if metaphysical, victory of an ancient warrior nation over modern cosmopolitanism. These values made reference to German romanticism and classicism and defied commercialism. For one of the most industrially advanced countries in Europe this was paradoxical. Yet this narrative contributed to the effort of papering over social and political divisions which were simultaneously held in check and exacerbated by war. What little evidence there is suggests this imagery favoured by the Junkers and military authorities in the Central Powers did not find much favour with the larger German population. As the effects of the war worsened, so did suffering and widespread shortages resulting in hunger and poverty. By the end of the war, these tensions erupted in revolution in Berlin, Vienna and Budapest.

These forces gave rise to a large number of posters published by the German, Austrian and Hungarian Communist Parties and other left-wing and socialist groups, on the one hand, and on the other, right-wing Freikorps and Stahlhelm organisations. They ranged in style from the cartoon-like to the emblematic. The left drew on what they understood to be a universal and expressive social realism and the right on Jugendstil as an existential national visual language.

Advertising and Propaganda↑

The distribution of posters was managed through existing structures. Banks and post offices provided useful networks for poster display sites, especially for war bonds. In Britain, party political machines and municipal authorities assisted army recruiting offices in distributing posters and leaflets for recruiting and war savings. By 1917, the declining market for product advertising and paper rationing saw billposting firms identify with the national cause and donate space on their hoardings. In America, artists, advertising and billposting agencies were under pressure from the government to donate their skill, space and time without charge. In France, schools were used to good effect for the placement of posters, poster competitions and in getting feedback on the effectiveness of war loans campaigns, while in Russia the Orthodox Church played out its familiar role of supporting the state.

Subject to strict censorship in Germany and Austria-Hungary, the regional military authorities saw little value in the use of posters until about 1916. Nevertheless, from the end of July 1914 when a state of siege was declared and the Reich was divided into Bavaria and twenty-four military districts, traditional rivalries in the field of print culture thrived. Munich, for example, was associated with Ludwig Hohlwein (1874-1949) and the design group Die Sechs; Berlin boasted Hollerbaum & Schmidt with its stable of Lucian Bernhard (1883-1972), Hans Rudi Erdt (1883-1925) and Julius Gipkens (1883-1968); Frankfurt claimed Lina von Schauroth. In Vienna, the Weiner Printing house monopolised the market for outdoor advertising and published Theodore Zasche (1862-1922), Alfred Offner (1879-1947) and Heinrich Lefler (1863-1919), among others. In Budapest the printing houses Biró Miklós Muintézete and Globus Muintézet counted among their number Mihály Biró (1886-1948) and Béla Moldován (1885-1967). Artists took responsibility for campaigns and often established entire graphic identities. Bernhard, for example, in what was seen as an important marketing inroad into official culture, drove the campaign for the fifth War Loan where posters ventured beyond bank interiors for the first time.

Poster display was confined to strictly defined areas and hoardings in banks, train stations, city streets, poster columns and to official events and displays. Poster sizes were standardised and relatively small in contrast to Britain and America where before the war posters had been as large as thirty-six sheets. Poster distribution was legal and regulated in Britain, America and France where posters were a taxed source of revenue. In Germany posters were criticized for their crass commercialism which grated on supporters of “traditional German Kultur.”

Overall, posters could be seen in Germany hoisted aloft in outdoor festivals and attached to speakers’ podiums in public spaces, held high in parades, displayed in and on schools, libraries, post offices, train stations, factories, offices, canteens, homes, commercial and municipal buildings, gable ends and church halls, distributed on public transport and vehicles and advertising kiosks. War posters made incursions into areas previously off-limits in a development which paved the way for the post-war commercialisation of urban space.

With the exception of those in the United States, the authorities and social elites in the combatant nations regarded the use of advertising techniques with suspicion as did large sections of the general public. Advertising was thought unworthy of the moral weight of the affairs of state, and for the Central Powers, myths of imperial and historical destiny. The British satirical magazine Punch called it “Govertisement”[18] and the war correspondent Philip Gibbs (1877-1962) remarked, “The New Army was called into being by…modern advertising methods to stir the sluggish imagination of the masses, so that every wall in London and great cities, every fence in rural places, was placarded with picture-posters.”[19] The “poster” election of 1910 had seen British political parties adopt advertising techniques and posters sported framed illustrations or cartoons with captions. Just four years later many PRC posters featured striking imagery and snappy, integrated slogans. The advertising expert Thomas Russell (1865-1931) observed in 1919,

The British and later the Americans dealt directly with the communications industry and brought people from the press, publicity and advertising into government. Max Aitken, Lord Beaverbrook (1879-1964), owner of The Daily Express and London Evening Standard, became Minister of Information and Alfred Charles William Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe (1865-1922), owner of the Daily Mail and The Times, was appointed to the Ministry of Information as Director of Propaganda in 1918. Additionally, government committees in Britain included Henry Wickham Steed (1871-1956), the journalist and expert on foreign affairs, Hedley Le Bas (1868-1926), the owner of the Caxton Advertising Agency, and Charles Frederick Higham (1876-1938), later the director of the Parliamentary War Savings Committee and owner of the eponymous advertising agency. This mutual understanding meant publishing houses such as David Allen & Co, Johnson Riddle & Co and Hill Sifken & Co, who contracted design work out to artists such as John Hassall (1868-1948), Bert Thomas and E.V. Kealey were given a large degree of autonomy in conducting official campaigns.

In America the situation was comparable. The CPI under George Creel engaged the services of Walter Lippmann (1889-1974), later to become an influential commentator on public opinion and Edward Bernays (1891-1995) who made his name in the 1920s as an expert on public relations and propaganda. The CPI was overwhelmingly successful in steering public opinion away from isolationism to interventionism. For Creel, "it was a plain publicity proposition, a vast enterprise in salesmanship, the world’s greatest adventure in advertising."[21] For Creel it was a battle for hearts and minds fought out before the jury of public opinion.

David Lloyd George (1863-1945) who gained the premiership in 1916 with the support of Northcliffe made his appointments for political reasons. His strategy had far reaching implications for the state, democracy and the communications industry. The latter along with the ruling elite were beginning to frame an understanding of the public defined by the reach of mass communication media. Higham and the influential political thinker Graham Wallas (1858-1932) in Britain and Creel, Lippmann, and Bernays in America were informed by early understandings of mass psychology promoted by Walter Dill Scott (1869-1955) and William Trotter (1872-1934) and influenced by Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) and Gustave Le Bon (1841-1931). For them the urban mass was irrational, thought in images and responded to base instinct. Therefore, the focus was on association and suggestion rather than "good design." Linked to the promise of political enfranchisement and, after 1917, fear of revolution, they established an influential school of thought in the political and business establishment and called for “organised and public persuasion.”[22] Paradoxically, once public opinion had been established as a factor in the life of democratic nations, it became rapidly clear that the same public opinion needed to be controlled and manipulated by a small and educated elite for government interests to be adequately supported.

In France, advertising was not as advanced and agents tended to be little more than space brokers. Professional artists were employed directly by the government or through established lithographic studios. To be an affichiste was just one aspect of what it meant to be a professional and academically trained artist: Georges Scott (1873-1943) worked for the army; Maurice Neumont (1868-1930) produced political propaganda; Theophile Steinlen engaged social themes; while Faivre was a ‘generalist.’ Maurice Neumont Studios and Devambez Printers in Paris carried out large numbers of poster commissions for the government, war loans and charities. With some notable exceptions in posters for entertainment, these works were little influenced by modern or commercial ideas of design. Instead they used established high art conventions derived from classicism, romanticism, realism and sentimental naturalism. The French government employed the resources of the state-controlled education system to display posters and gain feedback from the children and their families on the effectiveness of campaigns both inside and outside the schools. A series of educational posters by Victor Émile Prouvé (1858-1943), for example, told of the heroism of French servicemen. A school competition for the French Union National Wartime Providence and Savings Committee, in which many posters had a "design" quality absent from most French posters, confirmed the centrality of the schools for the government’s dissemination and creation of wartime ad campaigns.

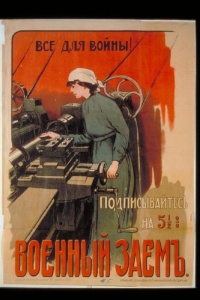

The development of graphic and poster design in Tsarist Russia is especially interesting and little documented. It drew upon the fashionable Art Nouveau, Secessionist and Jugendstil styles which lent themselves to the graphic interpretation of the Cyrillic alphabet. In combination with traditional motifs and narratives linked to national, historical and mythological figures, the Red Cross publishing house, for example, played on forms derivative of Byzantine icons and connotative of the church and monarchy to produce very rich and elaborate designs. Designs for war loans shared the bold, planar colour planes, heavy outlines, vivid contrasts and emphasis on a singular motif of the best of British and American commercial posters. In 1914, the publishing house Today’s Lubok produced a series of fifty posters aimed at stirring up feelings against the Central Powers. They traded on knowledge of folk epics and art to stimulate sentimental nationalism. The Futurist poet Vladimir Mayakovsky (1893-1930) produced the copy and the Suprematist artist Kasimir Malevich (1879-1935) executed the designs in a simple style using heavy black outlines and blocked colour. They aped the traditional lubok or woodblock print that later had a substantial influence on Bolshevik and socialist realist posters.

The Graphic Artist↑

In Central Europe, graphic production was focused on questions of design, society, aesthetics and education. Influenced by the arts and crafts movement, Hermann Muthesius (1861-1927), the theorist and founder of the Deutscher Werkbund, gave the artist a social role. He believed that commerce and manufacturing contributed to the cultivated life of the bourgeois classes and good design could improve quality of life. By the beginning of the war designers had developed the idea of the ‘new scientific poster.’ This approach required the artist to have a knowledge of business and the poster trade to take account of placement, size, quality of printing, restrictions on subject-matter, distribution, market, functionality and the quality and economy of design.[23] Derived from the object poster developed by Lucian Bernhard at Hollerbaum & Schmidt, a simplification of means and the exploitation of the characteristics of the lithographic medium were at its heart. Attention focussed on the artifact or brand and in the manner of a metonymic expression, an image of the part stood in for the whole. Typographical elements were integral to the overall design and the tendency towards abstraction encouraged the use of striking graphic schematics to demonstrate industrial production and supremacy in war materiel. This was evident in Louis Oppenheim’s (1879-1936) series "Are We the Barbarians." Other designs worked with maps, statistical information and the design possibilities of the letter “U” to propagandise the “success” of the U-boat campaign. Paradoxically, the approach easily accommodated the incorporation of heraldic and medievalising imagery in emblematic designs expressive of atavistic myths of origin which tapped into psychological constructions of the self and nation.

Similar techniques can be observed in many posters from Britain and America where the object, although rarely depicted in such radically abstracted style, was isolated against a vivid background in recognition that in the competition for visibility on crowded hoardings the background was as important as the image itself. The influence of this modern science of the poster can clearly be seen in the work of Bert Thomas in Britain and in many of the posters produced for the United States Food Administration.

At the outbreak of war the claims that the poster was an art could be supported by institutional structures. Even in Britain, where the poster was strongly associated with commerce and business, the Royal Society for the Arts in London received a lengthy address on the nature of the poster in October 1914. Contemporary histories of the poster were formulaic and once they had dispensed with cave painting and Egyptian hieroglyphs, continued with the art poster in France and the examples of Jules Chéret (1836-1932), Toulouse Lautrec (1864-1901) and Alfonse Mucha (1860-1939) before remarking on Art Nouveau in France, Jugendstil in Germany and the Secession in Austria. These fin de siècle decorative and abstracted styles were utilised by advertisers in France and Central Europe to market products to the fashionable middle classes where the advance of the high street and advertising were associated with liberal democracy, nationalism, modernity and individualism. Paradoxically, in Austria-Hungary the Secession was appropriated as the official art of empire to satisfy and suppress its nationalities and incorporate the rise of a growing professional middle class. In Central Europe, including Russia, the poster possessed a meaning quite apart from what it depicted as a herald of individual and national autonomy.

In Central Europe and France the poster was widely collected. In Berlin Das Plakat was the publication of The Society for Friends of the Poster. It had an international membership with several hundred American members by July 1914. Edited by Dr. Hans Josef Sachs (1881-1974) the magazine promoted the poster as an art and facilitated exchanges for collectors, art schools and museums. Publications in Britain such as The Billposter and The Placard focused on the nature of the trade and the importance of effective and elegant advertising. In America The Poster: The National Journal of Outdoor Advertising and Poster Art published in Chicago performed a similar function and championed the generally accepted view that Germany and Austria were preeminent in the field.

The fact that the poster was collected as a minor art form may have encouraged artists to produce designs with as much an eye towards the collectors’ market as the needs of the advertiser. The artistic ambition of many French, German and Austrian posters denied the economy of modern commercial design which had established their reputation. Erdt, Oppenheim and Gipkens all adapted their styles to accommodate the high seriousness and narrative essence of mythological and medievalist imagery within a formulaic and conservative romanticism, often drawing on literary quotation to enhance the gravity of the subject. Spectacular they may have been, but these martial posters did not resonate with the public whose concerns were rather more prosaic. Exceptionally, in Britain, Brangwyn’s poster designs were also available as lithographic prints from The Avenue Press, London; and in Paris Devambez printers marketed some posters as collectibles for the causes they supported. Institutions such as the Société des Beaux Arts and many art schools and commercial organizations in France and America ran poster competitions which had the capacity to work outside of the normal boundaries of poster production and to challenge the commercial parameters of the medium.

War Sells↑

Even during the war, early collectors such as Leslie R. Bradley (1892– 1968) at the Imperial War Museum in London recognised that the imagery of war in posters and printed ephemera was used to market products and often did so through appeals to patriotism, duty and the national interest. Postcard publishers in Britain, for example, had cards on sale within three days of the outbreak of hostilities. The selling of the war and the war as a marketing device were intimately connected: in the public imagination noble passions and the appetite for adventure coalesced with a vicarious fascination with the violence of war that commoditised service as easily as it sold products and newspapers.

Two advertisements for sparkling wine in France and Germany give us an indication of how deeply war aims infiltrated commercial discourse. In one, the lithographic full-length portrait drawing has a poilu waving his arms, bottles in hands and pockets, as he calls his comrades for a drink. In the other, the brightly coloured lithographic three quarter length portrait of a German officer is elegantly posed under the national flag and with glass in hand has an air of aloof superiority. The war was what interested the public the most and for many companies it was a very effective marketing device, invoking by association feelings of patriotism, duty and national pride. Advertisements designed to promote consumer products such as hand creams, soaps, disinfectants, tobacco, beer, ink, typewriters, hot drinks, books and films chained the rhetoric of the market to the language of the nation. An advertisement for Players’ Navy Cut cigarettes, for example, featured badly drawn portraits of prominent historical figures to prod “memories that arouse drowsy patriotism and strengthen shaken confidence.” A show card advertising The Grey’s Cigarettes featured an illustration of a full-blooded cavalry charge; one for Black Dawn Cigarettes put troops in a shallow trench over the caption, “Time for another one;” another for Dunlop shows a Tommy holding two cycle tyres after his bicycle has been blown from under him with the caption “Only me and DUNLOPS left.” The ideal of service with its disdain for personal safety, heroism and sacrifice was linked to branded products. Products new to the market were promoted within the discourse of modernity and embraced science, hygiene, efficiency, productivity and leisure. Advertisements for soap, razors and toothpaste products, for example, invoked cleanliness (next to godliness), hygiene (as much racial as bacteriological with the enemy identified with disease) and efficiency (technological superiority breeding moral as well as military dominance).

Advertisements not only aligned products with military superiority but also offered personal rejuvenation within the gendered spheres of wartime society. Men at the front were rested and refreshed. Women in the factory, field, office and hospital found their femininity revived by cosmetics. The rhetoric challenged traditional roles as quickly as it returned the newly independent woman to hearth and home from which the man was banished to the abjection of the front.[24] A significant difference in emphasis between the Allies and the Central Powers was summed up by Thomas Reece who wrote on British poster design for The Poster. He made the point that patriotic service could at the same time provide profit: ‘Business as Usual’ as the much-used British slogan expressed it. In a self-referential advertisement, a Tommy and a group of sailors encounter a poster for Sunlight Soap: a woman gazes invitingly out towards them, and, as if to emphasize the point, part of the text reads: "Sunlight Soap is made for profit for thereby can the makers hope to profit by Sunlight Soap."

The connection between corporate interest and the state emerged most strongly in America towards the end of the war. The Committee on Public Information and the War Industries Board provided the opportunities for advertising agents and corporations to link to the national cause. The Advertising Division of the CPI prepared material for YMCA, Liberty Bonds, the Red Cross and appeals for food and fuel conservation where companies paid for their name to appear. With the Third Liberty Loan in spring 1918 it launched the "duplex plan." Corporations supplied the copy for their products with the appeal for war bonds to join private enterprise with public life. Business was declared in the national interest. As we have already seen the connections in Britain and America between business and government were very close. Alongside goods war aims could be sold. As Roland Marchand points out, it is here we find the origins of corporate advertising.[25]

Black and Atrocity Propaganda↑

All combatant countries engaged in black propaganda which can be defined as material where the role of the authorities is deliberately obscured, or where it appears to have been composed by members of its target audience. The Dutch cartoonist Louis Raemaekers some of whose work was published covertly in Britain through the auspices and without the acknowledgement of the War Propaganda Bureau, for example, attracted a bounty from the German government because in their view, his attacks on the German leadership threatened Dutch neutrality.

The Americans, Austrians, British, French, Germans, Hungarians, Italians, and Russians engaged in leafleting enemy armies in order to undermine morale. The most effective means of delivery was the by aeroplane over the lines. A few early efforts in 1915 at leafleting the Germans from the air by the British were inspired by Alfred Charles William Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe (1865-1922) with the support of the Daily Mail, but were not followed up initially with any enthusiasm. Propaganda newspaper leaflets were produced by the Allies for the populations under German occupation in Belgium and France. Conveyed illicitly overland and dropped from the air, they included the French La Voix du Pays, the British Le Courrier de l'Air and La Lettre du Soldat produced by the Belgian Army in London. By 1916 the British, French and Italians had taken to the task in earnest and prepared leaflets which reproduced letters from German prisoners of war illustrated with photographs of them at leisure to provide evidence that they were well treated.

Pre-1917 Russian leaflets took the form of manifestos promising national liberation for the peoples of Austria-Hungary by exploiting the multi-ethnic character of imperial armies. They played well with Czechs in the Austrian army and counterpropaganda from the Germans played equally well with Poles in the Russian army. The Italians had the greatest success using this technique on Austro-Hungarian troops, producing hundreds of thousands of leaflets with the aid of Austrian, Hungarian, Slav, Croatian, Polish and Czech nationalists which called on them to desert and to throw off the yoke of empire. Air delivery amplified their effect because it emphasised Italian supremacy in the air. Many French leaflets took a similar approach to Poles and Bavarians who, they claimed, were treated as second class citizens by the Prussians. Also targeted were French speakers in Alsace Lorraine for whom Allied victory would bring liberation. Many leaflets distributed by the French were prepared by the American "Friends of German Democracy" which based much of their content on speeches made by American President Woodrow Wilson.

In 1916 the French dropped a series of newssheets known as the War Leaflet for the German People over German trenches. It appeared as though they originated in Germany. Along with bogus trench newspapers, communist and socialist material was scattered along the lines and over rest areas. Under changing titles they illustrated the joys of domesticity, the threat of American involvement, troop movements and conditions in Germany. The information was often conveyed in simple maps, diagrams and charts and was designed to sap morale and incite revolution. They also produced versions of German newspapers and copied and parodied leaflets used for war propaganda in Germany. One leaflet aped the cartoon style of the German satirical magazine Simplicissimus and showed a drawing of a naked, disabled serviceman who can only preserve his modesty because of the size of the tax demand he has received.

The Germans had supported left-wing agitators and revolutionaries in Russia since 1915. To foment unrest in 1917 they brought the news of the February Revolution and the arrest of Tsarist ministers to the Russian frontline troops by means of leaflets and placards held up above the parapets. Easter was a traditional period of fraternisation on the Eastern Front and the Germans targeted the new soldiers’ revolutionary committees to appeal for peace while, at the same time, the Russians attempted to foment revolution amongst the armies of the Central Powers. As the Russians retreated printed propaganda became more widespread and publications such as those produced for prisoners of war (POWs) such as Nedelia, the German Russki Vestnik and editions of the Viennese socialist daily Arbeiter-Zeitung supplemented by papers printed at the front such as Obzor and Posledniaa Izvestia were widely distributed.

By 1918 British leaflets were identified as stock or priority. Stock leaflets designated ‘AP’ dealt with allied war aims and the generic failings of German militarism. Many were illustrated with cartoons that played on the anxieties produced by war profiteering, the fate of the disabled, high mortality rates, and failure of leadership. They played on themes such as Germany’s responsibility for the war, the lack of success of the submarine blockade, the coming of the Americans with their manpower and materiel, Wilson’s fourteen points and the hopelessness of the German military situation. The drawings were dark and populated with the imagery of death, bereavement, mutilation and bedevilment. More extreme than the publically available and controversial work of Raemaekers and Dyson, they emulated French leaflets dropped by The Lafayette Flying Squadron and the Escadrilles des Armées since 1915. Priority leaflets, on the other hand, went out three times a week and responded directly to recent events. Composition, translation, printing, transport to France and distribution was cut to a minimum of 48 hours. In June 1918 1.7 million leaflets were released from balloons. This number rose to 5.4 million in October 1918. Hindenburg called it "English poison raining down from God’s clear sky" and in his memoirs he admitted that these propaganda efforts played a part in the demoralisation of the troops. Furthermore, the leaflets passed from hand to hand and made their way back to civilians, contributing to discontent on the home front.

American propaganda was organized through Creel’s CPI and General Pershing’s two sections, one run by Lippmann in Paris which saw to the printing of material, the other by Captain Blankenhorn at GHQ in Chaumont which saw to distribution.[26] Three million leaflets described the treatment of prisoners and the medical care, generous rations, security and promise of return that would come at the end of hostilities; repeated the words from Woodrow Wilson’s speeches and the Fourteen Points; attacked the monarchy and emphasized the sheer scale of American involvement on the ground. The prisoner leaflets which played on the racial segregation of the American Expeditionary Force were deemed particularly successful. The Germans countered with appeals to ‘Coloured Soldiers of the States’ offering them heated accommodation and good food if they surrendered. Evidence gained from interviews with prisoners taken in the last months of the war indicated that the scheme worked.[27] After November 1918 the Bolsheviks in Northern Russia proved equally adept at producing propaganda designed to undermine the BEF, US and French armies. Antony Lockley has argued that passing pamphlets and even lecturing across the lines contributed to the mutinies in February 1919, the defections of the Whites and British withdrawal in September 1919.[28]

Conclusion↑

From the evidence of the posters in extant collections it is clear that propaganda, publicity and advertising campaigns followed needs dictated to combatant governments and nations by the conditions of war. In this context, communications with various target audiences separated by class and wartime roles were defined in a complex field circumscribed by the relationships between design, national, commercial and political interests which varied over geography and time. Among the most important was the nature of the links between the communications industry, commerce, charities and government. As we have seen in Britain and the US, they were intimate and represented an important incursion by commercial discourse into government. Nevertheless, it must be remarked, a high proportion of posters from all sides took the form of official proclamations, which were typographical, declarative and uncontaminated by the techniques of advertising.

In the Central Powers, where design quality held sway over effective marketing and publicity, official campaigns were subject to military control and the relationship was sovereign, rather than result of a process of negotiation between the older establishment and a newly powerful professional elite born of a burgeoning communications industry. Lord Kitchener, for example, the Boer War hero famously disapproved of his image being used in recruiting posters, because he felt there was something improper about official discourse being infringed upon by commerce through the medium of the poster. At the same time, among all combatants, drinks companies and the manufacturers and marketers of new convenience products such as war bonds and savings certificates, typewriters, inks, pens, beverages, soaps, safety razors, instant soups, cosmetics and ointments and clothing for use at home and at the front made deliberate capital from national sentiment by emphasising their contribution to the war effort. In these ways, the communications and advertising industry as well as manufacturers felt themselves legitimised in the service of the country at a time when questions of nationality, workers’ rights and universal enfranchisement were becoming increasingly important issues for the wider public.

A sense of duty towards the men at the front and the importance of those at home to do their part was the focus of campaigns for War Loans and Savings among all the combatant nations. In France these campaigns addressed a sense of national community and egalitarianism, with the French people and Marianne as symbols of a democratic republic in a defensive struggle for national existence. Their style was lithographic and aimed at the whole population in equal measure. Slogans from war savings and loans schemes in Britain echoed with calls among representations of ordinary people to "Save for the Children," "Feed the Guns and Beat the Huns," "Bomb them with War Bonds" or "Bring Him Home with War Bonds," "You Buy War Bonds. We do the Rest!" "Back them Up!" and "Let’s Finish the Job." These vocabularies offered an alternative to War Bond campaigns which were habitually aimed at the established bourgeoisie. Their deployment of national symbols and historical and contemporary national figures drew on the "natural" authority of banks as commercial organisations operating in the national interest. Among the Central Powers there was a strong tendency to emphasise this approach and to supplement it with existential calls to ‘Join the Struggle’ and to contribute "Everything for the Homeland" in a "Cry of Rage" as "He Bears the Burden" in representations of soldiers, workers and families.

For the Allies, official campaigns were more often characterised by a vernacular and demotic visual and verbal rhetoric aimed at the individual serviceman and citizen as opposed to the state and nation. Paradoxically, this gave recognition to sections of the community hitherto ignored in the public discourse (40 percent of British troops fighting for freedom and democracy did not have the vote) and created a space where they could find a form of representation denied by the nation. Official campaigns simultaneously drew upon popular culture to encourage personal economy. Posters published by the Army sported the slogan “Any Old Iron” from the eponymous song popularised in 1911. The Ministry of Food used the popular saying “Waste not, Want not.” Prosaically, the Coal Mines Department at the Board of Trade urged people to take fewer baths, to burn cinders and to go to bed early to conserve coal. Similar official campaigns in the Central Powers from municipal authorities, the German Farmers’ Purchase Association and the War Committee for Oils and Fats emphasised the importance of the conservation and development of alternative raw materials for the production of war essentials. As the effects of the British Naval blockade were increasingly felt, posters addressed the salvage of metals, conservation of coal and emphasised the need for women’s hair, acorns, chestnuts, beechnuts and fruit stones for the war effort. In circumstances where the plight of the general population became increasingly desperate these campaigns were carried out by the private companies entrusted with the task using a commercial rhetoric that increasingly abandoned calls to duty, destiny and sacrifice. Often aimed at children and young people who were expected to harvest the material, a more playful verbal and visual vocabulary emerged with which the wider population could more easily identify. In other words, government campaigns in Britain and the US were controlled by experts in publicity and marketing rather than military censors or civil service bureaucrats. They captured an easy familiarity in their verbal and visual styles which was capable of embracing official policy, national cause and individual self-interest more effectively than the calls to national myth and sacrifice prevalent among the Central Powers. Propaganda in Britain and the US, where thinking on advertising and publicity was at its most advanced combined official and commercial interests in slogans and images such as Bert Thomas’ “Arf a mo’ Kaiser” advertisement for the Weekly Dispatch; Bruce Bairnsfather’s cartoons and dramatic productions, “A better ole,” featuring Old Bill; and the poster by the Canadian Arthur Keelor “Come On! Let’s Finish the Job,” which helped to define the popular experience of the war for the Allies.

Unlike the Bolsheviks, few recognised the importance of British and American developments in advertising, propaganda and publicity. Writers such as Mark Cornwall have remarked that returning German, Austrian and Hungarian POWS who had in their possession Bolshevik propaganda (itself partly funded by the German authorities) had a material effect on the revolutions in Berlin, Budapest and Vienna in 1919. For the victors, the war accelerated a growing awareness of the importance of the illusions deemed necessary for democratic states to sustain popular support. The penchant for supplying information was superseded by the desire to manipulate and control. At the same time, visual representation enhanced wider political enfranchisement as the public was identified through advertising and publicity as a potential market and a democratic citizenry. The self-recognition of wide sections of the public in visual discourses made legitimate by both government and commerce had in turn made the manipulation of the public they had defined all the more essential. By way of contrast, in the Central Powers and Germany in particular, campaigns provided the visual foundation for atavistic national and racial myths of racial superiority that fuelled the rise of fascism in the interwar years.

James Aulich, Manchester Metropolitan University

Section Editors: David Welch; Dominik Geppert

Notes

- ↑ See Eskilson, Stephen J.: Graphic Design. A History, London 2007; Gallo, Max: The Poster in History, Feltham, Middlesex 1975; Hollis, Richard: Graphic Design. A Concise History, London 2001; Meggs, Philip B. / Purvis, Alston W.: Meggs’ History of Graphic Design, Hoboken, New Jersey 2012; and Timmers, Margaret (ed.): The Power of the Poster, London 1998.

- ↑ The Poster Advertising Association and St. Clair, Liberty Loans 1919; such as Rickards, Maurice: Posters of the First World War. London 1968, Paret, Peter / Lewis, Irwin Beth / Paret, Paul: Persuasive Images. Posters of War and Revolution, Princeton 1992 and Aulich, James: War Posters. Weapons of Mass Communication, London, 2007 produced from museum collections. Burkan, Gary A.: World War 1 Posters, Atglen 2002 published for the collector.

- ↑ Price, Charles Matlack: Posters. A Critical Study of the Development of Poster Design in Contnental Europe, England and America, New York 1913.

- ↑ See Higham, Charles Frederick: Looking Forward. Mass Education through Publicity, London 1920; Blankenhorn, Captain Heber: Adventures in Propaganda, Boston & New York 1919; Steed, Wickham: Through Thirty Years, 1892-1932, London 1927; Creel, George: How We Advertised America. New York & London 1920.

- ↑ See Laswell, Harold Dwight: Propaganda Technique in the World War, New York 1927; Larsen, Cedric / Mock, James R.: Words that Won the War: The Story of the Committee of Public Information 1917-1919, Princeton 1939; Welch, David: Germany, Propaganda and Total War, 1914-1918, New Brunswick 2000; Messinger, Gary S.: British Propaganda and the State in the First World War, Manchester 1992; and Monger, David: Patriotism and Propaganda in First World War Britain. The National War Aims Committee and Civilian Morale, Liverpool 2012.

- ↑ Hiley, Nicholas: The Myth of British War Recruiting Posters, in: Imperial War Museum Review 11 (1997), pp.40-58.

- ↑ Sheldon, Cyril: A History of Poster Advertising, London 1937; Nevett, Terence, R.: Advertising in Britain. A History, London 1982; Pope, Daniel: The Making of Modern Advertising, New York 1983; Vaughn, Stephen L.: Holding Fast the Inner Lines. Democracy, Nationalism, and the Committee on Public Information, Chapel Hill 1980; and Marchand, Roland: Creating the Corporate Soul. The Rise of Public Relations and Corporate Imagery in American Big Business, Berkeley 1998.

- ↑ This was followed by an announcement on the front page of the Daily Mail from Lord Northcliffe following Louis Bleriot’s successful channel air crossing on 25 July 1909: “Britain is no longer an island!”

- ↑ Bryce, Right. Hon. Viscount: Report of the British Committee on Alleged German Outrages, London 1915.

- ↑ Unknown, printed by Hely’s, Dublin, July 1915.

- ↑ Unknown, published by the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee, No. 16, December 1914, printer Henry Jenkinson Ltd., Kirkstall Leeds.

- ↑ County Printers, Colchester and London EC4, published by the British Empire Union, undated.

- ↑ Reproduced in St. Clair, Liberty Loans 1919, p. 75.

- ↑ His cartoons “Fragments from France” were immensely popular and increased the sales of The Bystander magazine.

- ↑ Gibbs, Philip: Realities of War. London 1919.

- ↑ James, Pearl: Picture This. World War 1 Posters and Visual Culture, Lincoln & London 2009, p.2.

- ↑ Ponder, Stephen: Popular Propaganda. The Food Administration in World War 1, in: J&MC Quarterly 72/3 (1995), pp.539-550.

- ↑ Mr. Punch’s History of the Great War, London 1919, p.50.

- ↑ Gibbs, Realities 1920, p.57.

- ↑ Russell, Thomas: Commercial Advertising. Six Lectures at the London School of Economics and Political Science, London & NY 1919, p.258.

- ↑ Creel, How We Advertised America 1920, p.4.

- ↑ Higham, Looking Forward 1920, p.110. The idea found its fullest expression in Bernays, Edward: Propaganda. New York 1928.

- ↑ Dieckmann, Walter: Introducing Art into Poster Advertising, in: The Poster, Chicago 5/7 (1917), pp.55-60.

- ↑ Aulich, Jim / Hewitt, John: Seduction or Instruction? First World War Posters in Britain and Europe, Manchester 2007.

- ↑ Chatterton, C. O.: Printers’ Ink a Journal for Advertisers. 50 Years 1888-1938, New York 1938, p.160. Stuart, Sir Campbell: Secrets of Crewe House. The Story of a Famous Campaign, London 1920.

- ↑ Blankenhorn, Captain Heber: Adventures in Propaganda, Boston & New York 1919.

- ↑ The History of Air-Dropped Leaflet Propaganda, issued by The Psywar Society, online: www.psywarsoc.org/history.php (retrieved: 2 June 2013).

- ↑ Lockley, Antony: Propaganda and the First Cold War in North Russia, 1918-19, in: History Today 53/9 (2003), pp.46-53.

Selected Bibliography

- Aulich, James / Hewitt, John: Seduction or instruction? First World War posters in Britain and Europe, Manchester; New York 2007: Manchester University Press; Palgrave.

- Aynsley, Jeremy / Wolfsonian-Florida International University: Graphic design in Germany, 1890-1945, Berkeley 2000: University of California Press.

- Bruntz, George G.: Allied propaganda and the collapse of the German empire in 1918, Stanford; London 1938: Stanford University Press; H. Milford; Oxford University Press.

- Cornwall, Mark: The undermining of Austria-Hungary. The battle for hearts and minds, New York 2000: St. Martin's Press.

- Creel, George: How we advertised America. The first telling of the amazing story of the Committee on Public Information that carried the gospel of Americanism to every corner of the globe, New York; London 1920: Harper & Brothers.

- Frantzen, Allen J.: Bloody good. Chivalry, sacrifice, and the Great War, Chicago 2004: University of Chicago Press.

- Hardie, Martin / Sabin, Arthur K.: War posters issued by belligerent and neutral nations 1914-1919, London 1920: A. & C. Black.

- James, Pearl: Picture this. World War I posters and visual culture, Lincoln 2009: University of Nebraska Press.

- Kingsbury, Celia Malone: For home and country. World War I propaganda on the home front, Lincoln 2010: University of Nebraska Press.

- Koureas, Gabriel: Memory, masculinity and national identity in British visual culture, 1914-1930. A study of 'unconquerable manhood', Aldershot; Burlington 2007: Ashgate.

- Lasswell, Harold D.: Propaganda technique in the World War, New York 1927: Kegan Paul.

- Messinger, Gary S.: British propaganda and the state in the First World War, Manchester; New York 1992: Manchester University Press; St. Martin's Press.

- Mock, James R. / Larson, Cedric: Words that won the war. The story of the Committee on Public Information, 1917-1919, Princeton 1939: Princeton University Press.

- Monger, David: Patriotism and propaganda in First World War Britain. The National War Aims Committee and civilian morale, Liverpool 2012: Liverpool University Press.

- Paret, Peter / Lewis, Beth Irwin / Paret, Paul et al.: Persuasive images. Posters of war and revolution from the Hoover Institution archives, Princeton 1992: Princeton University Press.

- Rickards, Maurice: Posters of the First World War, New York 1968: Walker.

- Sanders, Michael / Taylor, Philip M.: British propaganda during the First World War, 1914-18, London 1982: Macmillan.

- St. Clair, Labert: The story of the liberty loans; being a record of the volunteer liberty loan army, its personnel, mobilization and methods. How America at home backed her armies and allies in the world war, Washington, D.C. 1919: James William Bryan Press.

- Stuart, Campbell: Secrets of Crewe House. The story of a famous campaign, London; New York 1920: Hodder and Stoughton.

- Vaughn, Stephen: Holding fast the inner lines. Democracy, nationalism, and the Committee on Public Information, Chapel Hill 1980: University of North Carolina Press.

- Welch, David: Germany, propaganda, and total war, 1914-1918. The sins of omission, New Brunswick 2000: Rutgers University Press.