Food Customs in Indochina in 1915↑

When World War I broke out, the journalist Phan Kế Bính (1875-1921) was working on a study of Vietnamese customs, including an in-depth look at foods eaten in Indochina. He published it in serialized form in 1915 in the Vietnamese-language journal Đông Dương Tạp Chí (Indochina Review). Phan Kế Bính looked primarily at the countryside, where most people lived, and described how rich, middle-class and poor villagers would eat on most days and how they might eat on special occasions.

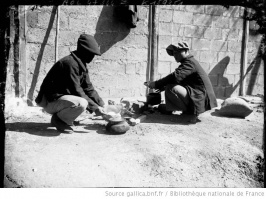

Both before and during the war, the wealthiest villagers had meat at most of their meals, sometimes beef or water buffalo, but more often pork, goat, duck, chicken, river turtle and many kinds of fish. On special occasions, they might eat dog meat or a dish of pork made to look and taste like dog-meat. At many meals, these rich villagers would have rice and fried noodles as well as charcuterie such as giò (pork loaf) or chả (pork paté rolls) and a variety of sautéed vegetables. Other villagers would have simpler meals, where fish or shellfish predominated along with beans, vegetables, tofu and rice.[1]

The poorest villagers could afford only cheap red rice and a little tofu along with foraged vegetables and some from their household garden - eggplants, cabbages, taro and other root plants and aquatic greens such as water spinach. Sometimes they found snails, shrimp or crab to supplement the vegetables and tofu. Northern villagers ate soy sauce daily, as nước mắm (fermented fish sauce) was more expensive. In the center and southern regions of Indochina, villagers used more nước mắm than soy sauce and also relished chili peppers.

On special feast days poor villagers might get to eat fish, meat and white rice. Feast days were also a time for particular sweet or savory rice treats. The third day of the third month of the year called for sticky rice balls stuffed with mung bean paste. On the June solstice people ate crispy rice wafers sprinkled with sesame seeds. Tết, the lunar New Year, was celebrated with bánh chưng, a square cake of steamed sticky rice stuffed with mung beans, pork and spices.[2]

In addition to his close analysis of cuisine in the countryside, Phan Kế Bính also wrote about special culinary occasions in the emerging colonial cities of Hanoi, Haiphong, Saigon and Cholon. Vietnamese people liked to show off their sophistication by inviting friends and family out to elegant French or Chinese restaurants.[3] French restaurants frequented by Vietnamese diners were often owned and operated by Chinese immigrants from the island of Hainan or by Vietnamese who had learned European cooking skills by working in a French-owned café in the colony and then moving on to open their own place.[4] With the start of hostilities in 1914, French and French-style restaurants faced new shortages of key ingredients. Urbanites encountered more culinary changes than did villagers, although everyone in Indochina was affected by the economic repercussions of a wartime decline in trade with Europe.

The Outbreak of War↑

When war broke out in 1914, the French government soon sent about 7,000 French troops in Indochina back to fight in Europe. Many of those men left wives and children in Indochina. The French military was legally required to ignore race in its decisions but in practice the military allocations council favored white wives over Asian wives in doling out monetary resources; over a hundred appeals appear in the military subsidy files.

Generally these women and their children were living in relative poverty while their soldier-husbands fought overseas in Europe. White women received daily subsidies of three piasters to pay for housing and food, plus one piaster per child. In contrast, Asian women and their Eurasian children received only half those amounts. The French state decided that households temporarily headed by an Asian woman had a lower cost of living compared to one headed by a white woman in Indochina. The unofficial policy was that white people, even poor white people, should not have to eat "native" food. In particular, the colonial state wanted white children to look healthy and well-fed in order to maintain white prestige. Officials were less concerned about the well-being of children who were only half white.[5]

In the first six months of the war, the French colonial government also forced Germans and Austrians to leave Indochina. Two pre-war import/export houses, Speidel & Co. and F. Engler & Co., were officially organized as French companies although in fact they operated under German control and German capital. The Speidel Company was the largest importer of European goods into Indochina and Engler was a major competitor. Low-level local employees tried to keep the businesses functioning after the German managers’ expulsions, but the colonial government harassed the companies into closing through the use of arbitrary customs enforcement, freight interference and regulatory aggravations.[6]

The French administration proceeded to seize Speidel & Co.’s warehouses full of German-owned perishables, from rice to canned goods and wine. In search of revenues, French officials sold the imported European foods at low prices to Vietnamese consumers and sold the rice to Chinese exporters. Vietnamese people were deeply suspicious of these Chinese export businesses. Export regulations kept changing during the first year of the war and Chinese buyers paid Vietnamese farmers minimal prices for their rice, passing along the risks of the export trade to those small farmers least able to bear it.[7]

Shipping difficulties due to the war led to the collapse of exports to Europe and imports from Europe. The volume of rice, corn, coffee, sugar and tea Indochina shipped to France fell to about a tenth of pre-war levels. Imports from Europe were also hard to obtain, although the colony’s import businesses worked to make up the difference with shipments of flour from the United States and dairy products from Australia. Before the war, Indochina had imported $950,000 annually in flour and $135,000 in condensed milk; during the war the colony only imported about half the amount of flour, nearly all from the United States, and imports of condensed milk fell to a fifth of their pre-war levels.[8]

Fortunately for Indochina, trade within Asia was much less affected by the war. Once the colonial government clarified export regulations, Indochina was able to restore its usual level of imports and exports simply by increasing its trade with China, Japan and Southeast Asia. During the war, Indochina received fewer shipments of canned goods from Europe but increased its imports of preserved vegetables and dried fruit from China. Imports of French wine and beer declined by half and two-thirds respectively. Imports of Chinese tea were also cut in half - perhaps because much of the Chinese tea had been re-exported to France before the war and now those re-shipments had stopped.[9]

In 1917 Indochina’s exports reached their highest levels ever, partially due to inflation but mostly due to several years of excellent rice harvests in Cochinchina and Cambodia, the southern regions. Annam, Indochina’s central region, Laos in the north-east and Tonkin in the north fared worse than the southern provinces. Annam’s sugar was too expensive to compete with other production around the world and Tonkin’s farmers could not find new markets for the corn they had been exporting to France where corn was used in galettes and other breads, in alcohol production and as animal feed.[10]

French Surplus Foods↑

At the same time as the French administration worked to liquidate Speidel & Co.’s stocks of European perishables, colonial grocers and importers were also seeking out new customers to relieve their warehouses overflowing with French food supplies, particularly wine and canned milk. Advertisements for a French milk company, La Petite Fermière, began running in the Vietnamese-language newspaper Lục Tỉnh Tân Văn (News of the Six Provinces) in January 1915.

The quarter-page advertisements were not simply an adaptation of generic publicity used in France and in French colonial newspapers. These pieces were specially tailored for the Vietnamese market. They showed Vietnamese people talking about the brand in Vietnamese, promoting French canned milk to each other and giving it to their children to make them healthy and strong. The canned milk advertisements even disparaged fresh, local milk which was provided by Tamil milkmen and hence (according to La Petite Fermière), must smell bad. Marketers portrayed imported milk as if it were a magic potion to ensure that a child had a modern, bourgeois lifestyle, potentially leading to a position in the French colonial administration.[11]

In the early stages of the war, prices dropped on many imported European products after so many French people were called from Indochina into military service back in Europe. Middle-class Vietnamese people began trying and enjoying French wine, beer, coffee, chocolate, jams and baguettes. Difficulties in transport meant that the stocks could not be quickly replenished. Prices for European imported food products went back up and then soared higher even than before the war. Consequently the Vietnamese stopped seeking out many of those exciting new tastes. Locally grown coffee did find a somewhat wider market during the war years as did the Larue Frères brewery in Cholon due to reduced competition from imported coffee and beer.[12]

Hunger and Military Recruitment↑

In the summer of 1915, Indochina’s northern rice fields flooded. On Bastille Day (14 July), the French military began a major fundraising drive for the war effort but soon realized that much of the money raised in the north had to be diverted to disaster relief to prevent political unrest in that province. Before the colonial period, Vietnamese emperors had supported devastated regions with rice from other parts of the country. The French government transported some rice from the south to the hungry northern provinces but also saw an opportunity: officials took advantage of the widespread starvation to recruit Vietnamese soldiers and workers for the European war effort. Masses of hungry northern villagers were sent to "charity" camps where they worked on public construction projects in exchange for food and a paltry wage. From those camps, recruitment into the military was quick and easy.

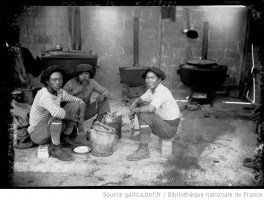

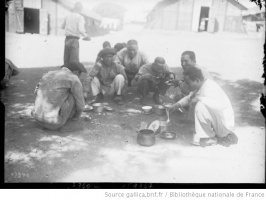

The French military in the metropole had been slow to demand Vietnamese troops because they believed them to be small and weak. Ultimately France transported about 50,000 Vietnamese soldiers and 50,000 Vietnamese workers to Europe during the war. New recruits from northern Indochina were indeed hungry and scrawny but commanders of the new troops noted that they filled out noticeably after a few weeks on a military diet. It took very little to improve their welfare from the starvation levels they had been experiencing. While still in Indochina, they ate local food at a minimal cost per recruit each day. The military at first assumed that these troops would switch to the French military diet once in Europe and issued them forks and knives.[13]

By November 1916, however, military inspectors decided it was better for Vietnamese soldiers and workers in Europe to try to replicate their customary cuisine as far as possible. It would save the French military considerable resources to use dried fish in place of fresh meat in their diet. One military inspector, Dr. Edouard Maurel (1841-1918), argued that too much meat would give Vietnamese recruits intestinal infections. He also believed that wine would overexcite the Vietnamese nervous system and lead to insubordination. Maurel and his supporters felt Vietnamese troops would be healthier and happier if able to prepare food and eat in their own fashion.[14]

Vietnamese troops, however, demanded the same rations as their French counterparts. An Inspector Jules Bosc (1871-1959) reported that the Vietnamese workers he observed looked robust and healthy on a French diet, though he supported their request to be allowed to substitute rice in place of bread. Once they were given those supplies, Vietnamese soldiers and workers insisted on preparing the rice themselves rather than trusting French methods. (After the war, some French authorities regretted the lost opportunity to have Vietnamese experts teach French soldiers how to make decent rice.)[15]

Vietnamese recruits also requested shipments of nước mắm fish sauce from Indochina. Until the war, French authorities did not see nước mắm as nutritious; they just saw it as a flavoring for rice that made the population’s staple food taste less bland. During World War I, the French military agreed to ship nước mắm to Vietnamese soldiers and workers in Europe. Scientists developed a process for dehydrating the fish sauce and reconstituting it in France. French scientists also began to study the condiment in light of new theories about vitamins. They discovered that when made of high quality ingredients and well-preserved, nước mắm enriched the Vietnamese diet with not just salt, but also amino acids, nitrates and other essential vitamins and minerals.[16]

Coming Home with New Tastes↑

One common French concern about recruiting Vietnamese for the war effort back in Europe was the reintegration of these colonial subjects back in Indochina after the end of the war. Most of them came to Europe as poor villagers, recruited from the underfed province of Tonkin. The Vietnamese middle classes had been experimenting with European foods and flavors, but it was a change to think of these poor Vietnamese soldiers and workers with experience eating French military rations or drinking in a French café after work in the metropole. Military inspector Gaston Du Vaure (1864-1928) asked, "When they return home, how will they meet their new needs, how will they reaccustom themselves to their national food? ...Recently they were even complaining that their bread was not fresh."[17] Inspector Du Vaure worried that the expectations of these Vietnamese had been raised too high; they would resent being pressured to reintegrate into their former life in poor villages.

French newspapers in Indochina likewise expressed anxiety about the returning soldiers and workers. In September 1918, the Tribune indigène said that the Vietnamese troops had been spoiled by socializing and drinking with lower-class French people in the metropole and would now not be willing to show due respect to French people in Indochina.[18] Conversely, the Vietnamese lawyer Dương Văn Giáo (1892-1945) mocked the idea that Vietnamese had been so well-treated in France that they were now spoiled for colonial life, remarking that Vietnamese had been worse paid than other workers during the war.[19]

French Substitute Local Foods↑

For the French people who stayed in Indochina during the Great War, it was harder than ever to recreate a semblance of a French diet.[20] Without regular shipments from Europe, prices of canned goods, flour, wine, beer and other foods kept rising. In 1916 Doctor Victor Le Lan (1863-1918) published a book to help his fellow French colonizers eat well while adapting to local produce and staples.

In place of olive oil, he recommended using denatured peanut oil: "you can even bottle it and stick on a pretty label saying Huile Vierge de Nice (Virgin Olive Oil from Nice) and no one will uncover your fib."[21] Potatoes did not grow well in Indochina but French people could satisfy a craving for pommes frites by blanching bamboo shoots, frying them briefly in hot vinegar, coating them in a frying batter and then frying the shoots in oil. Le Lan also suggested using unripe bananas in a stew: "guests will be amazed to taste such delicious potatoes."[22]

He discussed how to use local root vegetables to make a simulacrum of marrons glacés (candied chestnuts, a favorite French treat). A particular bean could substitute for lentils. He also explained that the common Vietnamese water plant rau muống could replace spinach purée and sorrel purée as side-dishes, be tossed in a green salad and serve as the base of a traditional French potage aux herbes (soup with green herbs).[23]

Le Lan recommended that French women not send their cook to market by himself, but go there themselves as well to explore all the possibilities:

He also suggested that French women in Indochina hire an intelligent young servant "who has never heard his compatriots describe French cuisine." Only by teaching him herself, guiding his practices and educating his tastes, would she end up with a cook who could make excellent French food from local ingredients.

Once trained, Le Lan promised that this cook would even be able make decent bread, which is "one of the things most difficult for us to forego." After a few months of experience, a Vietnamese cook would even be able to bake bread in a village in the remote countryside:

The contemporary French term pain K.K. referred to an ersatz bread: K.K. stood for "Kleie und Kartoffeln" (bran and potatoes) while also bringing to mind the rude word "caca." French people in Indochina during the war could not pretend to eat a normal French diet, but they could comfort themselves with reminders that their fellow citizens in France also faced wartime dietary changes.

Conclusion↑

For most people living in Indochina during World War I, their daily diet was influenced more by the usual issues of climate and crop yields than by the war itself. Due to increased trade within Asia, the colony did not suffer much economic pain during the war. However, the colony’s food supply was certainly affected by the war’s economic and social developments and some people faced significant upheavals in their culinary options. Wives of French troops faced reductions in their living standards once their husbands were called back to Europe. French people in Indochina learned to substitute locally available foods for many of the European imports they had enjoyed before the war. Finally, most of the Vietnamese people who continued to explore European foodways during the war were soldiers or workers living in France and separated from their families. The cultural and political education these tirailleurs and travailleurs received overseas, sitting in French cafés or eating the same foods as French troops, may indeed have made them more skeptical of the foundations of white prestige once they returned to Indochina after the war.

Erica J. Peters, Independent Scholar / Culinary Historians of Northern California

Section Editor: James P. Daughton

Notes

- ↑ Phan Kế Bính: Việt Nam phong tục (Moeurs et coutumes du Vietnam) [Customs and Traditions of Vietnam], volume II, Nicole Louis-Hénard (ed. and trans.), Paris 1975 [original printing 1915], p. 176.

- ↑ Phan Kế Bính, Việt Nam phong tục [Customs and Traditions of Vietnam] 1975, pp. 77, 174-177.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 11 and 17.

- ↑ Lafargue, Jean André: L’Immigration Chinoise en Indochine, sa réglementation, ses conséquences économiques et politiques. Paris 1909, p. 283; Tsai Maw Kuey: Les chinois au Sud-Vietnam, Paris 1968, p. 102.

- ↑ Firpo, Christina: Shades of Whiteness: Petits-Blancs and the Politics of Military Allocations Distribution in World War I Colonial Cochinchina, in: French Historical Studies 34/2 (2011), pp. 286-291.

- ↑ Centre des Archives d’Outre-Mer in Aix-en-Provence (hereafter CAOM): Archives of the Governor General of Indochina (hereafter GGI), dossier 19457: 20 November 1914 letter from Governor General Vollenhoven to the Minister of Colonies.

- ↑ Bulletin de la Chambre de Commerce de Saigon: minutes from 26 February 1915.

- ↑ Supplement to Commerce Reports (Deptartment of Commerce, Washington D.C.), No. 54b (16 December 1916), p. 6; Exporters' Encyclopaedia, New York 1917, pp. 807-808.

- ↑ Annuaire Statistique de l’Indochine, 1913-1922, Hanoi 1927, pp. 112, 168-169.

- ↑ Sion, Jules: Le commerce extérieur de l’Indochine, in: Annales de Géographie 29/157 (1920), pp. 72-73.

- ↑ Lục Tỉnh Tân Văn [News of the Six Provinces], 7 January 1915, 8. Other milk ads in Lục Tỉnh Tân Văn [News of the Six Provinces]: 25 February 1915, p. 3; 1 April 1915, p. 3; 6 May 1915, p. 3.

- ↑ Dương Văn Giáo: L’Indochine pendant la guerre 1914-1918. Université de Paris, thèse de la Faculté de Droit 1925, pp. 209-214.

- ↑ CAOM: Service de Liaison des Originaires des Territoires Françaises d’Outre-Mer (hereafter SLOTFOM) Series 1, Carton 1, dossier 1: 20 November 1916 report on indigenous recruitment in Indochina from August to December 1915. See also Favre–Le Van Ho, Mireille: Un milieu porteur de modernisation: travailleurs et tirailleurs Vietnamiens en France pendant la Première guerre mondiale, thesis for the Ecole des Chartes 1986, p. 234.

- ↑ SLOTFOM Series 1, Carton 1, dossier 12 : 7 November 1916 report by Doctor Maurel, Medecin Principal de la Marine en Retraite, Membre du Comité d’Assistance aux Travailleurs Indochinois de Toulouse, on the diet appropriate for Vietnamese in France.

- ↑ GGI, dossier 15670: 15 February 1917, “Note sur le groupement des travailleurs indochinois employés à l’Arsenal de Toulon”; Maspéro, Georges: Un empire colonial français, l'Indochine. Paris 1929, p. 147.

- ↑ Mesnard, J. and Rosé, E.: Recherches complémentaires sur la fabrication du nuoc-mam. In: Annales de l’Institut Pasteur 34 (1920), p. 646; Rosé, E.: Les nuoc-mam du Nord, in: Bulletin économique de l’Indochine 20/132 (1918), pp. 959-961, 972; Guillerm, J.: Le 'nuoc-mam' et l'industrie saumuriere en Indochine. Arch. Inst. Pasteur Indochine 7 (1928), pp. 21-60, 25.

- ↑ SLOTFOM Series 1, Carton 1, dossier 12 30 July 1916, letter from G. du Vaure to the President of the Comité d’Assistance aux Travailleurs indochinois.

- ↑ Favre–Le Van Ho, Un milieu porteur de modernisation 1986, p. 681.

- ↑ Dương Văn Giáo, L’Indochine pendant la guerre 1925, p. 135.

- ↑ Peters, Erica J.: Appetites and Aspirations in Vietnam: Food and Drink in the Long Nineteenth Century, Lanham 2012, pp. 150-170.

- ↑ Le Lan, Victor: Le Jardinage au Tonkin: Légumes indigènes & recettes pour les accommoder au goût français, Hanoi 1916, p. 94.

- ↑ Le Lan, Le Jardinage au Tonkin 1916, pp. 42 and 98.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 107-108.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 96.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 90-92.

Selected Bibliography

- Việt-nam phong-tuc. Mœurs et coutumes du Vietnam. Nicole Louis-Hénard, volume 2, Paris 1975: École française d'Extrême-Orient; A. Maisonneuve, 1975.

- Bureau de la Statistique Générale (ed.): Annuaire statistique de l'Indochine, 1913-1922, in: Annuaire statistique de l'Indochine, 1927.

- Dương Văn Giáo: L'Indochine pendant la Guerre de 1914-1918, Paris 1925: Jean Budry et Cie.

- Favre-Le Van Ho, Mireille: Un milieu porteur de modernisation travailleurs et tirailleurs Vietnamiens en France pendant la Première guerre mondiale, Paris 1986: Ecole nationale des chartes.

- Firpo, Christina: Shades of whiteness. Petits-blancs and the politics of military allocations distribution in World War I colonial Cochinchina, in: French Historical Studies 34/2, 2011, pp. 279-297.

- Guillerm, J.: Le 'nuoc-mam' et l'industrie saumuriere en Indochine, in: Arch. Inst. Pasteur Indochine 7, 1928, pp. 21-60.

- Lafargue, Jean-André: L'immigration chinoise en Indochine, Paris 1909: Universitaire de Bordeaux.

- Le-Lan, Victor: Le jardinage au Tonkin. Jardin potager, verger, jardin fleuriste, légumes indigènes et recettes pour les accomoder au goût français, Hanoi 1916: Impr. d'Extrême-Orient.

- Maspéro, Georges: Un empire colonial français, l'Indochine, Paris; Brussels 1929: Éditions G. Van Oest.

- Peters, Erica J.: Appetites and aspirations in Vietnam. Food and drink in the long nineteenth century, Lanham 2012: AltaMira Press.

- Rosé, E.: Les nuoc-mam du Nord, in: Bulletin économique de l'Indochine 20/132, 1918, pp. 959-961.

- Sion, Jules: Le commerce extérieur de l'Indochine, in: Annales de Géographie 29/157, 1920, pp. 72-73.

- Tsai Maw Kuey: Les Chinois au Sud-Vietnam, Paris 1968: Bibliothèque nationale.