Introduction↑

The First World War is justly labeled the first “media war”, as an unprecedented amount of energy was expended on conquering “hearts and minds” to bolster morale, convince domestic and foreign audiences of the justness of the cause, or demonise the opponent. The use of images was pivotal in distributing biased war information. Distinct from the written press, film appeared to offer direct access to “reality” and proved itself particularly capable of capturing emotions. Cinemas mushroomed throughout the Western world from 1906 onwards, attracting an international audience. During the First World War, film played a prominent role in the propaganda efforts of the belligerents, both at home and in the neutral countries. A case in point are the Netherlands, where the cinema business flourished.[1]

Since there were few Dutch photojournalists active in the war zone, let alone Dutch cameramen, the Netherlands was largely dependent on foreign imagery to envision the reality of war. From spring 1915 onwards, British, German, and French propaganda agencies were very active on the Dutch cinema front. A substantial number of these propaganda films – be it fiction films, newsreels, or documentaries – were widely discussed in the Dutch press. This was a relatively new phenomenon, as most newspapers still considered the cinema an inferior art form, or even a threat to moral society. In addition, some of these films, such as The Battle of the Somme (British Topical Committee for War Films, 1916) or Mères Françaises (Éclipse, 1917), could certainly be ranked among the most popular films of the time. Like no other media form, they appealed to a collective imagination.

Neutral Censorship↑

The first filmed images of the war appeared in Dutch cinemas by the end of August 1914, the Cinema Pathé in Amsterdam probably being first to screen them. While this French-owned cinema preferably showed its national product, other venues featured war imagery from the German and British side as well. As cameramen were not (yet) allowed near the front lines, the actual fighting remained out of sight, but audiences – including many Belgian refugees – did witness the ruins, bombardments, and overall devastation in Belgium. “It is certain that no other films are considered more interesting”, one of the largest Dutch newspapers wrote at the time.[2] The press praised these “oorlogsactualiteiten” (short non-fiction films that were somehow related to the context of war) for their realism, often called superior to the journalistic capacities of the illustrated or written press. The “war actualities” quickly occupied the newsreels that were conventionally shown at the beginning of each cinema program. Respectable cinemas even had their own war-themed newsreels: the “oorlogsjournaal” (“war journal”).

From the moment war-related films appeared in the public sphere of the cinema, anxieties grew about their effects on the audience. Following the government’s call for strict neutrality in every aspect of the public domain, local city councils played a key role in maintaining neutrality. If a city mayor deemed a certain film a threat to public order, he could decide to ban or cut it. In the cosmopolitan harbour town of Rotterdam, home to thousands of Belgians and Germans, the city council outlawed films that contained patriotic imagery from any of the warring parties (images of heads of state, flags, fighting scenes, et cetera). Cinema musicians were not allowed to play national anthems or other patriotic songs.[3] Neutral censorship did occur in the diplomatic hub of The Hague as well. For example, a Pathé newsreel was forbidden because it portrayed recognizable images of Albert I, King of the Belgians (1875-1934) and President Raymond Poincaré (1860-1934). The French fiction film Le Passeur de l’Yser (Pathé, 1915), featuring German soldiers looting a Belgian home, was also banned.[4] From May 1917 onwards, in The Hague, every war film had to be examined beforehand by local police officials. In many other parts of the country, war films were censored for various reasons. However, in typical fashion, the official stance towards war films in Amsterdam could be called fairly “liberal”. Here, for instance, the screening of Le Passeur de l’Yser was left unbothered. Much to the annoyance of the cinema trade, neutral film censorship often was a whimsical affair.

Most cinema owners and local distributors adhered to the principles of neutrality. It was common practice to warn audiences at the beginning of the program not to show any signs of (dis)approval: war films should be watched in neutral silence. In addition, distributors and cinema owners composed their newsreels of actualities from all sides of the conflict, thus practicing a neutralizing principle. This form of self-censorship resulted in the complete absence of “black” propaganda films such as The Kaiser, the Beast of Berlin (Renowned, 1918) or Le fusil de bois (Pathé, 1915). However, films that inventively disguised their true intentions could slip through the net. The most intriguing example is the American propaganda film The Battle Cry of Peace (Vitagraph, 1915), which ran for several months from August 1917 onwards. Although the plot is centered on the invasion of America by fictitious “Ruritanians”, their brutal actions, Wilhelmine moustaches, and beer consumption were clearly recognisable as stereotypically “German”.[5] Reviewing the film, the notorious non-neutral daily De Telegraaf even seized the opportunity to foreground its anti-German agenda: “One is under the impression of witnessing what we read about a certain army three years ago […] that more or less acted in the same way in Belgium.”[6] Nevertheless, despite German complaints, no explicit action was taken to prevent its further distribution. Apparently, the film did not lead to disturbances of public order.

The Official Films of the Entente↑

Notwithstanding their neutral façade, it soon became clear that not every Dutch cinema (or newspaper) responded to the government’s plea for neutrality. Instead, some functioned as an alternative public sphere for cinemagoers who felt the need to share their patriotic or partisan sentiments. Belgian refugees, expats, interned foreign soldiers, or whatever group that sympathized with one of the belligerents, could be treated as a target audience. Cinema Pathé in Amsterdam, for example, was widely known for its partisan programming and its “loud”, pro-French audience. As long as this cinema did not show explicit anti-German or other films that triggered fights or complaints, it was allowed to show patriotic war films.

The pre-war dominance of Pathé within Dutch cinema culture was at the heart of the French propaganda strategy in the Netherlands. The headquarters of their distribution branch in the Netherlands, Kinematograaf Pathé Frères, delivered French films to more than 70 Dutch cinemas on a regular basis.[7] With the establishment of the first government-backed film propaganda agency early 1915, the Section Cinématographique de l’Armée (S.C.A.), the French profited from the well-established distribution network of Pathé to get their message across. Although the import of foreign films was far from a sinecure in war-torn Europe, the S.C.A. succeeded in maintaining a steady flow of French supply to the Netherlands during the war years. The first official propaganda film that was shown in the Netherlands, Nos poilus en Alsace (S.C.A., 1915) certainly did not go unnoticed by the national press, nor were many other S.C.A. films that followed, including high-end productions such as L’offensive française de la Somme (1916) and La puissance militaire de la France (1917). The pro-French newspapers De Telegraaf and, to a somewhat lesser extent, the Algemeen Handelsblad, often reviewed French war films, applauding their strong patriotic appeal. In addition, the French launched large publicity campaigns in the trade press, even attracting the interest of future clientele by offering films for free.

In contrast to the French, the British could not profit from a firmly established distribution network in the Netherlands. Their foreign distribution policy was rather a laissez-faire affair. The establishment of the Wellington House Cinema Committee led to the first feature-length propaganda film, Britain Prepared (1915). The rights to distribute the film in the Netherlands were bought by an independent Dutch rental company: H.A.P. The owner, a highly talented businessman named David Hamburger (1867-1935), probably did not distribute the film because of his own political preferences. As Britain Prepared attracted British upper-class audiences, including members of the government, Hamburger understood very well this prestigious, official film could boost the reputation of his trade. On 14 June 1915, he held a press screening in his own Cinema Palace in Amsterdam (a fairly new phenomenon), to be followed by “elite-screenings” in other cities. These private gatherings, organized with the aid of sympathizing networks, were attended by diplomats, officers, politicians, and even members of the royal family. For the mutual benefit of both the cinema trade and the propagandists, the “elite-screening” was an integral part of film propaganda in the Netherlands.

The Success of The Battle of the Somme↑

The biggest event in Dutch cinema culture during the First World War was the release of the British documentary The Battle of the Somme, designed as a testimonial of the British advancements on the Western Front. The film was immensely popular: it was shown in every Dutch city that had a notable cinema. From its first press screening in Cinema Palace on 25 September 1916, The Battle of the Somme remained in circulation for months. Not a single (local) newspaper ignored the film. Again, distributor David Hamburger hit the jackpot.

By 1916, Dutch audiences seemingly had become bored with newsreels that showed nothing but preparatory action, parades, decorations, shot miles behind the front line trenches.[8] However, The Battle of the Somme offered an unprecedented, realistic experience of the battleground. “Never before I saw a similar, suggestive screening of the powers that kill and destroy”, a journalist of the Algemeen Handelsblad stated, and numerous fellow commentators used similar wordings.[9]The Battle of the Somme was generally labeled (and praised) as an anti-war film in the Dutch press.[10] While the majority of existing sources do not convey any discontent for the British point of view, critical interpretations did exist. The Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant was skeptical about the film’s alleged pacifist message, as was the explicitly pro-German magazine De Toekomst, which condemned the film for its ruthless propaganda.[11] From religious and socialist camps, the film was attacked for its use of violent imagery and appraisal of militarism.

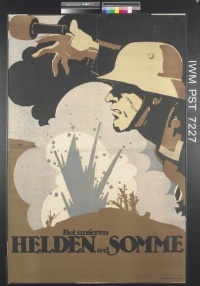

Could The Battle of the Somme be considered a success? From a commercial point of view, it probably was. While quantifiable data such as attendance rates is lacking, a wide array of written sources that have survived seem to indicate that The Battle of the Somme was one of the most popular films in Dutch cinema culture during the First World War. When compared to the reception of other Somme-films such as the L’offensive française de la Somme and Bei unseren Helden an der Somme (BuFA, 1917), The Battle of the Somme undoubtedly was considered more sensational. In sharp contrast to everything seen before (and afterwards), it contained graphic images of the dead and wounded, thus catering to the morbid desires of sensation seeking audiences.[12] Lacking a similar “spectacular” quality, Bei unseren Helden an der Somme remained virtually unseen. Moreover, the lower classes, who made up for most cinemagoers, were generally more in favour of the Entente.[13] After its premiere in Amsterdam, Bei unseren Helden an der Somme was soon withdrawn from the market. Some newspapers, including the Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant did discuss the film briefly, but it certainly wasn’t treated as an “event”. When compared to the release of its British counterpart in the Netherlands, it could even be considered a failure.

Dutch Film Propaganda: Leger- en Vlootfilm↑

Strongly influenced by the popular appeal of Britain Prepared, the Dutch government ordered the making of a similar film: the Leger-en Vlootfilm (Army and Navy Film, Willy Mullens, 1917). This documentary did not mark the birth of Dutch film propaganda. As early as August 1914, director and cinema owner Willy Mullens (1880-1952) had signed a contract with the Dutch army that earned him the exclusive rights to film military scenes for instructional and promotional use. Right after the beginning of the war, these short films were also shown in several commercial cinemas under the title “mobilization films”. With the Leger- en Vlootfilm however – lasting 150 minutes – the Ministry of War took its “impression management” to another level. The film was to serve two basic purposes. Firstly, it was meant to highlight the army’s activities and key role in maintaining Dutch neutrality, and combat the image of Dutch soldiers standing idly and passively. Second, as nation-wide dissatisfaction was growing, the Leger-en Vlootfilm would demonstrate that the permanent state of mobilization and the huge costs involved actually paid off. By emphasizing the parole (both home and abroad) that the Dutch army could stand the test of battle, Holland Neutraal countered any critique concerning its preparedness. The Leger-en Vlootfilm was also shown in Surinam, Curaçao, Venezuela, and possibly other countries, although little is known about its reception abroad.

The first “elite-screening” of the Leger-en Vlootfilm took place on 9 January 1917 in Mullens’ own cinema, the Residentie Bioscoop in The Hague. Prime Minister Pieter Cort van der Linden (1846-1935) was one of the invitees, as was Minister of War Nicolaas Bosboom (1855-1937), Commander-in-Chief Cornelis Jacobus Snijders (1852-1939), and many other government officials. Their presence was eclipsed by Wilhelmina, Queen of the Netherlands (1880-1962), who publicly attended a cinema screening for the first time. “A great honor for that little, intimate cinema hall”, the Catholic newspaper De Tijd wrote, no doubt much to the delight of its owner.[14] The Leger-en Vlootfilm certainly was effective propaganda for cinema business. With regard to its official intentions however, opinions differed. The well-known professor, lawyer, and publicist Joost Adriaan van Hamel (1880-1964) called the film, “an event […] especially because the government and military authorities had dared to use the popular medium of the cinema to present the facts to the public.”[15] The film was front page news in almost every newspaper. While most press reactions were positive, socialist newspapers such as Het Volk and De Tribune fiercely condemned the film for its overt militarism, even supporting local demonstrations against the film.[16] In other media too, the Leger-en Vlootfilm was mocked for its hyperbolic rhetoric.

Echoing the lingering fear that the Dutch government could not safeguard the neutrality of the Netherlands Indies, the Leger-en Vlootfilm met more widespread criticism here.[17] According to the Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad for example, the film proved the Dutch army “could surely match the foreign forces – for example those of Costa Rica.”[18]

German Shortcomings↑

Mimicking the pro-Entente attitude of most Dutch moviegoers, German propaganda films were hardly ever noticed by the national press. The prestigious war film Wenn Völker streiten (Apollo, 1915) is illustrative in this respect.[19] The story of two friends (one German, the other French) separated by the war, appeared to take a humanist stance, but its propagandistic intent was thinly veiled. By addressing their gentlemanly behaviour in war, the film clearly put the Germans in a favourable light. While (local) newspapers completely ignored the film, the trade journal De Bioscoop-Courant used it to denounce the ban on Le Passeur de l’Yser, reminding its readers that Wenn Völker streiten was left unbothered “while the Belgian exodus was still fresh in our minds.”[20]

The invasion of Belgium, the execution of Edith Cavell (1865-1915), the sinking of Dutch ships, and similar war crimes hampered Dutch sympathies for the German cause. The officials of the Bild- und Filmamt (BuFA), established as late as January 1917, meticulously monitored Dutch cinemas for anti-German sentiment and Entente successes. They were well aware of their shortcomings. “In Holland sind Beifalls-und Missfallenskundgebungen an der Tagesordnung,” one of them reported, adding that these surreptitious acts of support were never in favour of the Germans.[21]

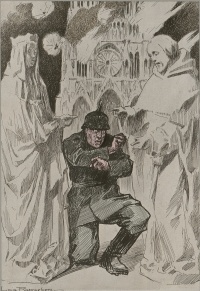

The French propaganda film Mères Françaises was one of those films envied by the BuFA. The tragic life story of aristocrat Jeanne d’Urbex (played by Sarah Bernhardt (1844-1923)) foregrounded universal themes of maternal love and the horrors of war. The film concealed its anti-German agenda well, yet clearly propagated the moral superiority of the French. Like The Battle of the Somme, this film neatly matched the dominant attitude of Dutch audiences towards the war. Mères Françaises drew large audiences, especially in the southern regions, where many Belgian refugees lived. It functioned as a blueprint for more “subliminal” propaganda fiction films as Der Gelbe Schein (PAGU, 1918), that had its German premiere on 22 November.[22] Consequently, it was not seen in the Netherlands until after the war (March 1919).

The absence of a distribution network also problematized the spread of German film propaganda in their neighbouring country. By the end of the war, with the aid of the financially strong Universum Film Aktiengesellschaft (UFA, founded in November 1917), the front company NV Neerlandia bought several Dutch cinemas in order to construct a chain of cinemas of their own.[23] Although the UFA would certainly benefit from this strategy after the war, its efforts were too little too late to battle Allied propaganda.

Conclusion↑

Film did not undermine Dutch neutrality during the First World War, but the cinema offered multiple opportunities for Dutch audiences to make sense of the war. French and British propaganda films were more appreciated in the Netherlands than their German counterparts. Dutch audiences also seemed to have an appetite for realism: films that were believed to show the true nature of war, such as The Battle of the Somme and Mères Françaises, were highly favoured over films that were considered patriotic or propagandistic.

As much as war films prompted cinema audiences in Holland to think about their own political position and identity, they also altered existing notions about film. Being a media event par excellence, the First World War gave way to new conceptions and debates about the relationship between film, politics and “the real”. By November 1918, both newspapers and the trade press had somehow acknowledged the new role of the cinema as a political instrument. There already was a growing awareness that the cinema had become a major force in the moulding of public opinion.

Klaas de Zwaan, Universiteit Utrecht

Section Editors: Samuël Kruizinga; Wim Klinkert

Notes

- ↑ van der Velden, Andre / Thissen, Judith: Spectacles of Conspicuous Consumption. Picture Palaces, War Profiteers and the Social Dynamics of Moviegoing in the Netherlands, 1914-1922, in: Film History: An International Journal 22/4 (2010), p. 454.

- ↑ Uitgaan [Going out], in: Algemeen Handelsblad (avondblad, evening paper), 30 October 1914, pp. 6-7.

- ↑ Rotterdams Archief, Rotterdam. Archief Gemeentepolitie Rotterdam, 63/166. Announcement Chief Commissioner of Police Adriaan Hendrik Sirks, 30 August 1915.

- ↑ Familie Bioscoop [Cinema Family], in: De Bioscoop-Courant 5/35, 25 May 1917, p.14.

- ↑ De Zwaan, Klaas / Gerber, Adrian: The battle for meaning: A cross-national film reception analysis of The Battle Cry of Peace in Switzerland and the Netherlands during World War I, in: Early Popular Visual Culture 14/2 (2016), pp. 168-187.

- ↑ Leo: De strijdkreet om vrede [The Battle Cry of Peace]. Cinema “De Munt”, in: De Telegraaf (ochtendblad, morning paper), 28 August 1917, p.6.

- ↑ Montant: La propagande exterieure, 1362. By 1914, there were around 200 cinemas in the Netherlands.

- ↑ Oorlogsfilms en oorlogsjournaals [Warfilms and war newsreels], in: De Bioscoop-Courant 3/26, 19 March 1915, p. 6.

- ↑ Uitgaan. Cinema Palace, in: Algemeen Handelsblad (avondblad, evening paper), 26 September 1916, n.p.

- ↑ Kristel, Conny: Propagandaslag. Nederlandse reacties op de Britse film 'Battle of the Somme' (1916) [A propaganda battle. Dutch reactions to the British film 'Battle of the Somme' (1916)], in: Kraaijestein, M. / Schulten, P. (eds.): Wankel evenwicht: neutraal Nederland en de Eerste Wereldoorlog [Keeping balance. Dutch neutrality and the First World War], Soesterberg 2007, pp. 344-365.

- ↑ De Entente-propaganda per bioscoop [The propaganda of the Entente in cinema], in: De Toekomst 2/34, 18 November 1916, p.740.

- ↑ De Zwaan: De dood op het doek. The Battle of the Somme als mediagebeurtenis in Nederland [Death on screen. The Battle of the Somme as a media event in the Netherlands], in: Buelens, Geert (ed.): Plots hel het werd. Jacobus van Looy en de Battle of the Somme [A Sudden Blaze. Jacobus van Looy and the Battle of the Somme], Rimburg et al., 2016, p.84.

- ↑ van der Velden / Thissen, Spectacles of conspicuous consumption 2010, pp. 460-461.

- ↑ Legerfilm [Army film], in: De Tijd: godsdienstig-staatkundig dagblad, 10 January 1917, p.7.

- ↑ van Hamel, Joost Adriaan: De Regeeringsfilm [The government film], in: De Groene Amsterdammer 2065, 20 January 1917, p.1.

- ↑ De bioscoop propagandiste van het militarisme [The cinema as a propagandist for militarism], in: De Tribune: Sociaal-Democratisch Weekblad, 8 January 1917, p.4.

- ↑ van Dijk, Kees: The Netherlands Indies and the Great War 1914-1918. Leiden 2007, p. viii.

- ↑ Batavia, in: De Kinematograaf 275, 26 April 1918, pp. 3605, 3608.

- ↑ The German film magazine Lichtbildbühne called it “der prächtigste Kriegsfilm unserer Zeit.” Wenn Völker straiten…, in: Lichtbildbühne 8/8, 1915, p. 43.

- ↑ Censuur en … nog eens censuur [Censorship ... again], in: De Bioscoop-Courant 5/36, 1 June, 1917, p.1.

- ↑ Bundesarchiv, Berlin. Auswärtiges Amt, R901/71961. Letter from the Kaiserlich Deutsche Gesandtschaft, The Hague, to Reichskanzler Max von Baden.

- ↑ Rother, Rainer: Learning from the Enemy. German Film Propaganda in World War One, in: Elsaesser, Thomas, et al. (ed.) A Second Life. German cinema's first decades, Amsterdam 1996, p.8.

- ↑ Blom, Ivo: Business as usual. Filmhandel, bioscoopwezen en filmpropaganda in Nederland tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog [Film trade, the cinema and film propaganda in the Netherlands], in: Binneveld, Hans et al. (eds.): Leven naast de catastrofe. Nederland tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog [Life beside the Catastrophe. The Netherlands during the First World War], Hilversum 2001, p.141.

Selected Bibliography

- Blom, Ivo: Business as usual? Filmhandel, bioscoopwezen en filmpropaganda in Nederland tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog (Business as usual? Film trade, the cinema and film propaganda in the Netherlands), in: Binneveld, Hans / et al. (eds.): Leven naast de catastrofe. Nederland tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog (Life beside the catastrophe. The Netherlands during the First World War), Hilversum 2001: Verloren, pp. 129-143.

- Dijk, Kees van: The Netherlands Indies and the Great War, 1914-1918, Leiden 2007: KITLV Press.

- Eversdijk, Nicole: Kultur als politisches Werbemittel. Ein Beitrag zur deutschen kultur- und pressepolitischen Arbeit in den Niederlanden während des Ersten Weltkrieges, Münster 2010: Waxmann.

- Groot, Wouter / Dibbets, Karel: Welke Slag aan de Somme? Oorlog en neutraliteit in Nederlandse bioscopen, 1914-1918 (Which Battle of the Somme? War and neutrality in Dutch cinemas, 1914-1918), in: Tijdschrift voor Geschiedenis 122/4, 2009, pp. 508-521

- Kristel, Conny: Propagandaslag. Nederlandse reacties op de Britse film 'Battle of the Somme' (1916) (A propaganda battle. Dutch reactions to the British film 'Battle of the Somme' (1916)), in: Kraaijestein, Martin / Schulten, Paul (eds.): Wankel evenwicht. Neutraal Nederland en de Eerste Wereldoorlog (Keeping balance. Dutch neutrality and the First World War), 2007, Aspekt, pp. 344-365.

- Messinger, Gary S.: An inheritance worth remembering. The British approach to official propaganda during the First World War, in: Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 13/2, 1993, pp. 117-127.

- Montant, Jean-Claude: La propagande extérieure de la France pendant la première guerre mondiale. L'exemple de quelques neutres européens, thesis, Lille 1989: Atelier national de reproduction des thèses.

- Mühl-Benninghaus, Wolfgang: Vom Augusterlebnis zur Ufa-Gründung. Der deutsche Film im 1. Weltkrieg, Berlin 2004: Avinus-Verlag.

- Reeves, Nicholas: Cinema, spectatorship and propaganda. ‘Battle of the Somme’ (1916) and its contemporary audience, in: Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 17/1, 2006, pp. 5-28.

- Rother, Rainer: Learning from the enemy. German film propaganda in World War I, in: Elsasser, Thomas (ed.): A second life. German cinema’s first decades, Amsterdam 1996: Amsterdam University Press.

- Sas, T. P.: Holland Neutraal. De Nederlandsche Leger- en Vlootfilm 1917 (Holland neutral. The Dutch army and fleet film 1917), in: Andriessen, Hans / Dorrestein, Leo / Pierik, Perry (eds.): De Grote Oorlog. Kroniek 1914-1918 (The Great War. Chronicle 1914-1918), volume 27, Soesterberg 2013: Aspekt, pp. 189-248.

- Velden, Andreas Wilhelmus Tarcisius van der; Thissen, Judith: Spectacles of conspicuous consumption. Picture palaces, war profiteers and the social dynamics of moviegoing in the Netherlands, 1914–1922, in: Film History: An International Journal 22/4, 2010, pp. 453-462.

- Véray, Laurent: 1914-1918, the first media war of the twentieth century. The example of French newsreels, in: Film History: An International Journal 22/4, 2010, pp. 408-425.

- Zwaan, Klaas de; Gerber, Adrian: The battle for meaning. A cross-national film reception analysis of 'The Battle Cry of Peace' in Switzerland and the Netherlands during World War I, in: Early Popular Visual Culture 14/2, 2016, pp. 168-187.