Introduction↑

In 1914, Denmark was among the leading film industries worldwide. Nordisk Films Kompagni, founded in 1906 in Copenhagen by Ole Olsen (1863-1943), was the dominant company producing hundreds of films a year and exporting most of these abroad, more than 95 percent of productions was exported before the war.[1] The war, especially the cultural and trade war, ended this dominant position, which Danish cinema never regained.

The literature on early Danish cinema and particularly Danish war films is not overwhelming; of the more recent literature, the Danish film historian Marguerite Engberg has written the standard reference work on Danish silent cinema, Dansk stumfilm: De store år vols. 1-2 (Danish silent film: The great era, 1977), and many books and articles on different aspects of Danish cinema. In English, she has written the short survey Danish Films – Through the Years (1990) and, of special interest here, “Nordisk in Denmark” from the book Film and the First World War (1995) about Danish war films. A thorough overview of the literature on Danish cinema can be found in Jan Nielsen’s monumental book – nearly 1,000 pages and in Danish – A/S Filmfabriken Danmark (2003). The American film historian Ron Mottram wrote The Danish Cinema Before Dreyer (1988), which treats the beginning of Danish cinema and several of the films mentioned below. The British film historian Andrew Kelly has written about the Danish screen version of Die Waffen nieder! in the article “Film as Antiwar Propaganda. Lay Down Your Arms(1914)” (1991) and in the first chapter of his book Cinema and the Great War (1997), “The first pacifist film of the war.” And in 100 Years of Nordisk Film (2006), different film scholars tell the story of the oldest and most influential Danish film production company.

Aside from these and other books, the most important source for the present article is the Danish Film Institute in Copenhagen (DFI), whose website contains invaluable information about different films, actors, directors, etc. Some films are available online on the website, and numerous programmes, stills, posters, and other surviving material have been digitised there.

Danish Prewar Films↑

The subject of war already appeared in Danish films before 1914, and it has been an obvious theme for cinema – documentary and fiction alike – from the early days of the art form, with the American film Tearing Down the Spanish Flag (1898) usually regarded as the first war film in the history of cinema.[2] War would also soon emerge as a theme in Danish cinema, although neither in the first Danish film, the cinema pioneer Peter Elfelt’s (1866-1931) ten meter fake documentary Kørsel med grønlandske Hunde (Driving with Greenland Dogs) shot in December 1896 in a park in Copenhagen, nor in Elfelt’s first – and the first Danish – dramatic film narrative: Henrettelsen (The Execution, 1903).[3]

A few years later, however, the theme appeared in different forms in several Danish films. The first example was part of Nordisk Film’s “First Danish programme”, as it states, 15 September 1906. The programme consisted of two fictional or feature films and two reportage films, all produced by Ole Olsen’s company. One of the short reportage films is called Fæstningskrigen. Fra de store Øvelser ved Københavns Befæstning (The Siege-War. From the Great Manoeuvres at the Fortifications of Copenhagen), which is a newsreel about the actual manoeuvres of the Danish army as the description in the programme points out.[4]

An early example of a feature film about a war related topic is En moderne Søhelt (A Modern Naval Hero, 1907) with the multi-artist Robert Storm Petersen (1882-1949) playing a naval officer.[5] This was followed by some films with historical settings, most importantly the ambitious screen version of the author H.P. Holst’s (1811-1893) popular patriotic-epic poem “Den lille Hornblæser” (1849) about the First Schleswig War, 1848-1851. The film Den lille Hornblæser (The Little Bugler) by director Eduard Schnedler-Sørensen (1886-1947) was loosely based on the poem and shot during the summer 1909 by Nordisk’s rival Fotorama in Aarhus, with actors from the local theatre and dragoons and infantrymen from the Aarhus garrisons. The film was a great success and led Fotorama and other companies to shoot more “national films” dealing with war.

The Schleswig Wars on Screen↑

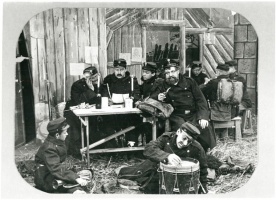

The following years, at least three Danish films treated the traumatic defeat in the Second Schleswig War of 1864: H.O. Carlsson wrote and directed Forstærkningsmanden or Minder fra 64 (The Reservist or Reminiscences of 64), which premiered 20 March 1910; a “military history play,” whose authenticity is underlined by the use of original guns and uniforms from the arsenal in Copenhagen, the poster points out.[6] Urban Gad (1879-1947) and Alexander Christian (1881-1937) directed a film version of colonel Peter Frederik Rist’s (1844-1926) partly autobiographical novel En Rekrut fra 64 (A Recruit from 64, 1889) for the new company A/S Kinografen in 1910. Gunnar Helsengreen (1880-1939) directed the tragic “national war play” En Helt fra 64 (A Hero from 64, released 26 January 1911) for Fotorama.

The reason for producing these films about the 1864 war might have been the approaching anniversary – even though it would have made more sense to wait for the actual 50th anniversary in the spring of 1914; more likely it was due to the success of Den lille Hornblæser. The strongly anti-German tendencies of the films about the Schleswig Wars disappeared from Danish cinema after the First World War broke out in August 1914 and Denmark was declared neutral.

Danish War Films 1914-1918↑

Closer to the outbreak of the First World War, some Danish films treated war with a focus on recent conflicts instead of historical wars. These films, inspired by and thematising the Balkan Wars, include Vilhelm Glückstadt’s (1885-1939) Krigskorrespondenter (War Correspondents, 1913) and melodramatic spy stories like Den kvindelige Spion fra Balkan (The Female Spy from Balkan, 1912).[7] A newspaper advertisement for Krigskorrespondenter describes the film as “an image of the horrors of modern war” indicating that a critical approach to war could be seen as a selling point and not just a moral position before the war.[8] One could say that the way was paved for the anti-war stance that was to become a prominent aspect of Danish war films. However, war continued to be presented as adventure and melodrama as well.

Lay Down Your Arms! (1914)↑

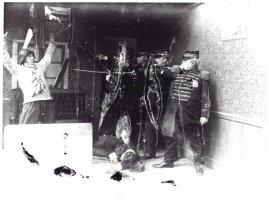

The most influential early Danish war film was the screen adaption of the Austrian 1905 Nobel Peace Prize winner, Baroness Bertha von Suttner’s (1843-1914) famous anti-war novel with the Danish title Ned med Vaabnene! (Lay Down Your Arms, 1889). The film was shot during late April and May 1914, so it does not deal with the World War.[9] It was directed for Nordisk by Holger-Madsen (1878-1943) and the script was written by Carl Th. Dreyer (1889-1968), who had the idea to purchase the rights to the book.[10] The film is much in keeping with the novel’s style, described in the American programme as “a pathetic story superbly acted,” containing “gigantic, startling battle scenes” and as “a picture with a purpose […] the most powerful argument for universal peace ever advanced.”[11] Only a few year later, the battle scenes appeared neither gigantic, nor startling in the light of Verdun or the Somme.

The premiere of the film was planned to be at the 21st International Peace Congress, scheduled to start on 15 September 1914 in Vienna in honour of Bertha von Suttner. The Baroness died 21 June 1914, before the shots in Sarajevo and the collapse of the hopes for a peaceful future; the congress was cancelled. Instead, the film was first shown in the United States in the autumn of 1914, and released in Denmark almost a year later on 18 September 1915. For a modern viewer, the battle scenes and the general approach to war in the film appear melodramatic and highly dated, as already mentioned, which also seems to have been the case for contemporary viewers as the harsh realities of the real modern war soon changed the way war was perceived. Yet, it did influence especially the American public and politicians at the beginning of the war. Andrew Kelly writes that the film “was finished too late to have an impact on the outbreak of war, although its release in the United States […] was used to endorse President Wilson’s neutrality proclamation issued at the start of hostilities.”[12] Likewise, it was received by the Danish public as a powerful glimpse into the futility of war and therefore also there as a support for the country’s neutrality.

The Spy as a Theme↑

Another war related topic – and typically a highly melodramatic and entertaining one – was the spy, which appeared in Danish cinema during as well as before the war in films about the Balkan Wars and two German-produced spy films directed by Urban Gad with Asta Nielsen (1881-1972):Die Verräterin or Den store Elskov (The Traitor or The Great Love, 1911) and S.1 (1913).[13] A wartime example of a spy film is Dansk Biofilm’s Flyverspionen (The Aviator Spy), which was released 18 January 1915 and which deftly combines two of the hottest topics at the time: spies and aeroplanes. The ambitious film – the programme states that it consisted of no less than 90 scenes – was directed by Alexander Larsen (1888-1964). However, besides its contemporary themes, it does not seem to be influenced by or related to the real war.[14]

Another spy film produced by Nordisk and directed by Robert Dinesen (1874-1972) was released just three days later: Mit Fædreland, min Kærlighed (My Country, My Love, 1915). The film was also titled Spionen (The Spy) and exported to France, Spain, Portugal, Britain, the USA, and even Germany – or it was at least given titles in these languages.[15] The English title given at DFI is Through the Enemy’s Lines, which stresses the dramatic spy story rather than the love aspects of the Danish title. Finally, A.W. Sandberg (1887-1938) directed De røvede Kanontegninger (The Stolen Siege Gun Plans) for Nordisk in 1914; a film from which only 14 stills seemingly have survived, and from these, the genre seems to be a spy or crime film rather than a war film.[16]

Pro Patria (1916)↑

In February 1916, Nordisk released a regular war film: Pro Patria, directed by August Blom (1869-1947) and with the greatest Danish male film star at the time, Valdemar Psilander (1884-1917), in the leading role (Psilander tragically died at age 32 the following year).[17] The film tells the story of an unexpected war between two unspecified neighbouring countries – the names on both sides sound German – including a melodramatic love story. General von Wimpfen’s daughter, Elsa, is engaged to Lieutenant Alexis von Kirkhowen, a military attaché at the neighbouring state’s embassy in von Wimpfen’s country. When war is declared, the general forbids his daughter to see Alexis, who is now his enemy. Lieutenant Alexis returns to his native country and joins the army and, while at the front, he hears about a planned surprise attack on the enemy. A traitor has revealed that the enemy commander-in-chief, General von Wimpfen, will oversee the consecration of colours at the traitor’s battery and blow up a gun, after which the attack will start. Alexis is shocked by this cowardly scheme and decides to warn Elsa via a carrier pigeon she has given him to use if he is in danger. Elsa’s brother, Lieutenant Erich von Wimpfen, played by Psilander, races to his father’s rescue, gets there at the very last moment, saves his father, and helps fight back the enemy and take their trenches.

Among the fallen is Alexis, who defended the last enemy trench, Lieutenant Erich tells Elsa, who volunteered as a nurse at the beginning of the war and who is stationed at a camp hospital nearby. They search the battlefield together and find Alexis – who is still alive. The enemy only has one fortress left, which Erich volunteers to attack single-handedly. He blows up the fortress’s powder magazine, whereupon his comrades attack and thus the war is won. Miraculously, Erich has survived, and after the war they all meet again in the general’s home – including Alexis, whom the general now welcomes as his son in law.

The plot is rather melodramatic and unrealistic. According to Mottram, Pro Patria “takes a pro-war stand and seems to imply that war is just a matter of honour in which enemies really respect each other.”[18] Nevertheless, the film was a great success in Denmark, if different advertisements from Viktoria Teatret cinema in Copenhagen are accurate.[19]

A similar melodramatic plot can be found in Robert Dinesen’s I Farens Stund (The Fortunes of War), which was released 22 November 1915,[20] and in Holger-Madsen’s patriotic tragedy Krig og Kærlighed (War and Love), released towards the end of the war on 23 September 1918. This film tells the story of a young officer torn between his love and his duty towards his country. The moral of the film clearly states that the duty which the soldier owes to his country precedes all others – even that of his love. This late in the war, a 1914-like approach to patriotism seemed to be passé and the film does not appear to have been successful. Marguerite Engberg writes that this film – along with Pro Patria, Mit Fædreland, min Kærlighed, and De røvede Kanontegninger – was shot in late 1914 as an attempt by Nordisk to cash in on the success in the USA of Lay Down Your Arms, but that it had become “difficult to accept Nordisk Films Kompagni’s comic opera officers after the World War had broken out.”[21] Already at the time of its Danish release, the newspaper Politiken wrote about Pro Patria that it had been made “shortly after the outbreak of the war, before the experiences about modern warfare obtained during the past year and a half,” and that the film therefore “is not quite modern when it comes to military matters.”[22]

Pax æterna (1917)↑

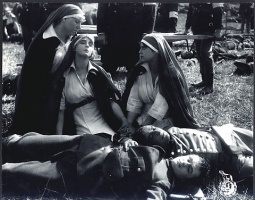

Holger-Madsen returned to the pacifism of Lay Down Your Arms in the ambitious anti-war drama Pax æterna (Peace on Earth), written by the author Otto Rung (1874-1945) and Nordisk’s Ole Olsen, and released 16 February 1917. This film tells the melodramatic story of another unspecified country, whose old, peace-loving king dies, whereupon the country is forced into a war with the neighbouring state. Bianca, the daughter of an old professor, who has dedicated his life to the cause of peace and written the book Pax æterna, is the heroine of the film. She joins the Red Cross – as the archetypical female figure of the real war did. Her brother and his best friend, who comes from the neighbouring state, meet on the battlefield and are both killed. Towards the end of the film, Bianca leads a peace delegation from the International Red Cross, which is chosen to carry out the young male hero of the film King Alexis’ peace plan, and delivers a powerful – albeit silent – speech at a conference, which secures the eternal peace. Finally, the lovers Bianca and King Alexis are married.[23] In the programme, the war is referred to as a meaningless horror, in line with the dominant way the war was regarded among the neutral Scandinavians who saw themselves as belonging to a more peaceful and civilised race. The film was introduced by a prologue by the author Sophus Michaëlis (1865-1932) which also carried a strong pacifist tone.

A similar approach to war is found in some other films released by Nordisk towards the end of the war and shortly after the armistice, especially in the ambitious science fiction film Himmelskibet (A Trip to Mars), directed by Holger-Madsen and written by Michaëlis and Ole Olsen. The film, which was released 22 February 1918, tells the story of a trip to Mars, as the English title indicates, where the primitive war-prone earthlings encounter a peaceful and far more developed culture among the Martians. Michaëlis expanded on the theme in his 1921 novel version of the story, in which he added a story from the trenches: in a brutal hand to hand battle, the glasses of a soldier’s gas mask are shattered, he inhales the lethal gas, but is saved by the space ship on its way to Mars. In the end, however, it appears that it was just a dream and that the soldier has died.

Conclusion↑

Danish war films reproduced the established genres at the time and were focused on the lucrative export markets before and during the start of the war. Consequently, the dominant genre was the melodrama, which seamlessly fitted both heroic and especially tragic anti-war films that became the method of narrating the war in a small neutral country. Still, an export oriented film industry like that of the Danish, especially Nordisk Film, was forcefully impacted by the increasing number of warring nations and, in particular, the loss of the US market. In the late 1920s, when an anti-war frame became the dominant way of understanding the war, Hollywood became the unquestionable leader of world cinema and Nordisk was not able to use its former strength and knowledge about this particular genre.

Danish films dealing with war in more or less direct ways and especially the ones dealing with and shot during the First World War did so without directly criticising the belligerents, in particular the southern neighbour, Germany. The trauma of the 1864 war and the loss of the Danish speaking parts of Schleswig was, understandably, avoided as a topic, as was the German U-boat war against neutral merchant ships. As shown above, Danish films dealing with war during the war years principally treated the topic in tragic, anti-war/pacifist and indirect manners, depicting the nations at war in the films as generic nations. Thus, the “Danes” forced to fight in the German army were not included as a theme – for example, there was no adaption to the screen of Erich Erichsen’s (1870-1941) immensely successful war novel Den tavse Dansker (1916) published in English as Forced to Fight (1917) – nor was the struggle of Danish seamen.

The war at sea and the experiences of Danish seamen – the most direct involvement of the neutral Danes resulting in about 700 seamen losing their lives at sea – were treated in some contemporary novels, poems, and most prominently in Christian Bogø (1882-1945) and J. Ravn-Jonsen’s (1881-1946) play Barken Margrethe, which was premiered 26 December 1918 at Aarhus Teater, and which became one of the biggest successes in Danish theatre history. However, the screen version of the play from 1934 turned it into a typical Danish popular comedy, altogether leaving out any trace of the war.[24] After the war, however, some wartime themes can be found in Schnedler-Sørensen’s 1927 film Grænsefolket (“The Border People”). The film was based on a short story by the author Hans Hartvig Seedorff (1892-1986), with screenplay by Laurids Skands (1885-1934), and it tells the story of a couple of “Danish” brothers during the war.

As Nils Arne Sørensen writes in his overview article about Denmark and the First World War, the Second World War and the years of occupation have almost completely overshadowed the first great war in the Danish collective memory and historiography alike – as well as a theme for contemporary Danish cinema. The Second World War keeps emerging in Danish films, most recently in Roni Ezra’s film 9. april (April 9, 2015) about the German occupation of Denmark in 1940 or in Martin Zandvliet’s drama about the immediate post-war days in Under sandet (Land of Mine, 2015), narrating the story of a group of young German prisoners of war who are forced to remove mines on the west coast of Jutland. Contrary to this, the First World War appears in neither post-Second World War films, nor in recent ones. In 2014, the 150 anniversary of the Second Schleswig War resulted in a high profile TV series by Ole Bornedal, whereas the First World War was left in the dark – perhaps unsurprisingly, since the Danish First World War was a war without fighting and thus without the dramatic narratives related to either heroic victories or traumatic – and possibly also heroic – defeats.[25] In Denmark, the dominant war experience became that of the profiteers, the remote activities of the seamen, or the war by proxy of the “Danes” in Northern Schleswig. The latter fought for the old enemy, so their experiences were difficult to adapt to a Danish narrative in a meaningful way, at least before the “reunification” of Northern Schleswig and Denmark in 1920.

Bjarne Søndergaard Bendtsen, Independent Scholar

Section Editor: Nils Arne Sørensen

Notes

- ↑ Engberg, Marguerite: Danske stumfilm i USA. Om modtagelsen af danske film i USA i årene 1914-1930 [Danish silent films in the USA. On the reception of Danish films in the USA from 1914-1930], in: Sekvens, pp. 103-104.

- ↑ See e.g. Westwell, Guy: War Cinema. Hollywood on the Front Line, London 2006, pp. 10-11.

- ↑ Mottram, Ron: The Danish Cinema Before Dreyer, London 1988, pp. 11-12.

- ↑ See Engberg, Marguerite: Dansk stumfilm. De store år [Danish silent film. The Great Years], vol. 1, Copenhagen 1977, pp. 45-47.

- ↑ Online: http://www.dfi.dk/faktaomfilm/film/da/36197.aspx?id=36197 (retrieved: 25 January 2017).

- ↑ Online: http://www.dfi.dk/faktaomfilm/film/da/35491.aspx?id=35491 (retrieved: 31 January 2017).

- ↑ See online: http://www.dfi.dk/faktaomfilm/film/da/15854.aspx?id=15854 (retrieved: 24 January 2017).

- ↑ Nationaltidende, 19 May 1913, p. 4. Translated by the author of this article as are the other Danish quotations.

- ↑ Engberg, Dansk stumfilm 1977, p. 499. In English, see Kelly, Andrew: Film as Antiwar Propaganda. Lay Down Your Arms (1914), in: Peace & Change. A Journal of Peace Research, 16/1 (1991) pp. 97-112, and his book Cinema and the Great War, New York 1997, pp. 4-14.

- ↑ The script is digitized at http://www.carlthdreyer.dk/Filmene/Ned-med-Vaabnene!.aspx (retrieved: 2 February 2017). See also online: http://english.carlthdreyer.dk/Films/Ned-med-Vaabnene!.aspx (retrieved: 1 March 2017).

- ↑ The American programme and other material including streaming of the film available online at: http://www.dfi.dk/faktaomfilm/film/da/14189.aspx?id=14189 (retrieved: 2 February 2017).

- ↑ Kelly, Cinema and the Great War 1997, p. 4.

- ↑ Online: http://www.dfi.dk/faktaomfilm/film/da/21602.aspx?id=21602 and http://www.dfi.dk/faktaomfilm/film/da/21221.aspx?id=21221 (retrieved: 2 February 2017).

- ↑ Online: http://www.dfi.dk/faktaomfilm/film/da/35414.aspx?id=35414 (retrieved: 24 January 2017).

- ↑ Online: http://www.dfi.dk/faktaomfilm/film/da/15908.aspx?id=15908 (retrieved: 31 January 2017). According to The Library of Congress’ Catalog of Copyright Entries. Cumulative Series. Motion Pictures 1912-1939 (1951), the film was exported to the USA as The Spy already on 23 January 1915. The catalog also contains the films The Stolen Siege Gun Plans, The Fortunes of War (both 15 March 1915), Pro Patria (6 May 1915), and of course Lay Down Your Arms (7 November 1914).

- ↑ Online: http://www.dfi.dk/faktaomfilm/film/da/32931.aspx?id=32931 (retrieved: 31 January 2017).

- ↑ The film can be seen at http://www.dfi.dk/faktaomfilm/film/da/15907.aspx?id=15907. DFI says that the film was released in Spain nearly a year before on 5 April 1915.

- ↑ See Mottram, The Danish Cinema 1988, p. 162.

- ↑ See e.g. Berlingske Tidende, 1 March 1916, p. 4.

- ↑ Online: http://www.dfi.dk/faktaomfilm/film/da/32933.aspx?id=32933 (retrieved: 1 March 2017). The film was shot in the autumn of 1914.

- ↑ Engberg, Dansk stumfilm 1977, p. 509.

- ↑ Politiken, 22 February 1916, p. 6.

- ↑ For a full synopsis, see Mottram, The Danish Cinema 1988, pp. 218-219.

- ↑ See Bendtsen, Bjarne Søndergaard: Neutral Merchant Seamen at War. The Experiences of Scandinavian Seamen During the First World War, in: Ahlund, Claes (ed.): Scandinavia in the First World War, pp. 338-340. Info on the 1934 film at: http://www.dfi.dk/faktaomfilm/film/da/14428.aspx?id=14428 (retrieved: 4 February 2017).

- ↑ However, a Danish-German co-production about a “Danish” Northern Schleswiger titled I krig og kærlighed (In war and love), directed by Kasper Torsting, is planned to be released on the centenary of the armistice.

Selected Bibliography

- Engberg, Marguerite: Dansk stumfilm. De store år (Danish silent film. The great years), 2 volumes, Copenhagen 1977: Rhodos.

- Engberg, Marguerite: Nordisk in Denmark, in: Dibbets, Karel / Hogenkamp, Bert (eds.): Film and the First World War, Amsterdam 1995: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 43-49.

- Jensen, Bernhardt: Da Århus var Hollywood. Et kapitel af stumfilmens historie (When Aarhus was Hollywood. A chapter in the history of silent film), Århus 1969: Universitetsforlaget i Aarhus.

- Kelly, Andrew: Cinema and the Great War, London; New York 1997: Routledge.

- Kelly, Andrew: Film as antiwar propaganda. 'Lay down your arms' (1914), in: Peace & Change 16/1, 1991, pp. 97-112.

- Mottram, Ron: The Danish cinema before Dreyer, Metuchen 1988: Scarecrow Press.

- Neergaard, Ebbe: The story of Danish film, Copenhagen 1963: Det Danske Selskab.

- Nielsen, Jan: A/S Filmfabriken Danmark. SRH, Filmfabriken Danmarks historie og produktion (A/S Filmfabriken Danmark. The history and production of SRH, Filmfabriken Danmark), Copenhagen 2003: Multivers.

- Richter Larsen, Lisbeth / Nissen, Dan (eds.): 100 years of Nordisk Film, Copenhagen 2006: Danish Film Institute.

- Sundholm, John / Thorsen, Karen / Andersson, Lars Gustaf et al.: Historical dictionary of Scandinavian cinema, Lanham 2012: Scarecrow Press.