Drum’s early Career and Arrival in France↑

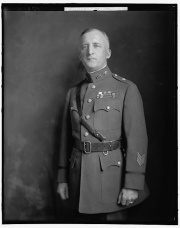

Hugh Drum (1879-1951) first entered the military when he volunteered for service during the Spanish-American War at the age of twenty. His boldness and verve in battle, combined with his father’s high rank and death during the conflict, earned him entry into the Regular Army during the Philippine Insurrection. After a successful stint as a staff officer during the 1914 Vera Cruz incident, Drum served with distinction in the 1916 Punitive Expedition into Mexico.

General John J. Pershing (1860-1948), Commander of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), took notice and hand selected Drum to be among the staff that set up his command in France. Pershing put Drum in charge of the staff group responsible for analyzing points of debarkation and rail lines within France, determining logistical and troop movement routes. Once completed, Pershing again reached out to Drum, ordering him to establish a staff school mimicking the Leavenworth model to teach Division and Corps staff officers the finer points of large-scale combat operations. The staff school focused on the intricacies of planning large-scale operations, logistics, and coordinating the various branches of the AEF.

First Army Chief of Staff and Operational Planning↑

Pershing decided to build the foundation of the AEF’s First Army, the first American combat designated command in France, around Drum, naming him the army’s Chief of Staff on 4 July 1918. Drum played a leading role in the First Army’s plan to attack the St. Mihiel Salient, the first opportunity for the AEF to assume sole responsibility for an offensive operation on the Western Front. Planning for the St. Mihiel Offensive revealed an overarching philosophy of American strategy – an adherence to “open-warfare doctrine.” Many in the AEF considered the primary problem among the Entente to be a lack of offensive spirit; the trenches had dulled their thinking and forced them into tunnel-vision planning that focused on massive firepower and limited objectives to taking the next trench line. American planners envisioned far more open formations that allowed aggressive leaders to capitalize on local opportunities, with the hope that it would lead to breaking through German defenses. With this in mind, Drum hounded his staff to plan first- and second-day objectives far in advance of the line of departure. Unwittingly, the withdrawal of German forces concurrent with the start of the attack on 12 September 1918 appeared to validate open-warfare doctrine.

Drum and the AEF would not experience the same amount of luck during the subsequent Meuse-Argonne Offensive. A far-more intricately prepared German defensive scheme awaited the U.S. attack. Drum again planned for the execution of open-warfare, gambling that the AEF could gain ten miles of ground on the first day of the operation, 26 September 1918. The divisions and men they assigned to the assault, however, had little experience, and the complicated nature of the attack plan caused serious confusion throughout the line. For over a month, the AEF ground forward, suffering a haunting number of causalities as officers and men gained experience under fire.

War’s End and Later Career↑

Drum played an integral role in the war’s closure, particularly the undisciplined sprint towards Sedan. A symbolic prize, Sedan sat behind German lines in the French Fourth Army’s sector. Pershing, still smarting from the repeated belittling of U.S. capabilities from their allies, gave verbal orders for the American First Army to capture Sedan. In accordance with Pershing’s wishes, Drum ordered a general advance, declaring “Boundaries will not be considered binding.” Thus began a haphazard and disorganized race towards Sedan that witnessed divisions and brigades crossing in front of and intermingling with each other. The advance to Sedan proved to be an ignominious end to the AEF’s and Drum’s war.

Following the war, Drum became the commandant of the U.S. Army’s Command and General Staff College. He garnered notoriety during the inter-war period as an ambitious political maneuverer, particularly with his near-constant clashing with General Billy Mitchell (1879-1936) over the attempted founding of an independent Air Corps outside of Army control. In 1939, President Franklin Roosevelt (1882-1945) selected Drum’s old assistant, George Marshall (1880-1959), as the next Chief of Staff of the Army, frustrating Drum. He would not hold combat command during World War II. He died in 1951.

Andrew J. Forney, United States Military Academy

Section Editor: Lon Strauss

Selected Bibliography

- Coffman, Edward M.: The war to end all wars. The American military experience in World War I, Lexington 1998: University Press of Kentucky.

- Cooke, James J.: Pershing and his generals. Command and staff in the AEF, Westport 1997: Praeger.

- Grotelueschen, Mark E.: The AEF way of war. The American army and combat in World War I, Cambridge; New York 2007: Cambridge University Press.

- Trask, David F.: The AEF and coalition warmaking, 1917-1918, Lawrence 1993: University Press of Kansas.

- Vandiver, Frank Everson: Black Jack. The life and times of John J. Pershing, College Station 1977: Texas A & M University Press.