Pre-war Experience↑

William J. Donovan’s (1883–1959) First World War experiences greatly contributed to his style of leading the nation’s first central intelligence agency during the Second World War. After growing up in a hard scrabble Irish neighborhood in Buffalo, New York and completing law school at Columbia, where he was a classmate of Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945), Donovan married and practiced law in Buffalo. There, he founded a National Guard unit, pejoratively known as the “silk stocking boys,” that was called up for the Mexican border turmoil in 1915. With no formal training, he taught himself tactics, drill, and strategy by reading all he could on his own.

42nd Division↑

Fighting 69th↑

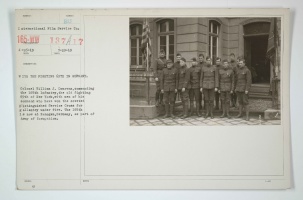

In March 1917, Donovan joined the 69th Division in New York City, believing that the United States would enter the war and the “Fighting 69th” stood a better chance of getting there faster. In August, the unit became part of the 42nd Division, or the “Rainbow Division”, a collection of Guard regiments from twenty-eight states.

Donovan was strict, but well-respected among his men. He attempted to embolden his men by wearing more formal uniforms, with plenty of shiny insignia that made him easily identifiable on the frontline. Fighting headquarters as much as the Germans, he successfully avoided being reassigned to staff work, while moving up the promotion ladder and staying in combat.

Leadership↑

Donovan rigorously enforced six basic issues with his soldiers concerning their job: ammunition on hand, communications, hygiene, looking out for one another, remaining focused on the task at hand, and keeping them alive. He also drilled them mercilessly. After one session in France through barbed wire in full gear and weapons, he remarked that he was older than his men and asked why they were short of breath. One of his soldiers replied: “But hell, we aren’t as as wild as you are, Bill.”[1] That comment quickly made him “Wild Bill” Donovan, a name he eschewed in public but secretly loved.

Relationship to Superiors↑

Douglas MacArthur (1880-1964) did not appreciate Donovan’s “running wild”, as he put it, during the Saint-Mihiel offensive when Donovan pushed his battalion out in front of supporting units, including MacArthur’s. However, that ability of pushing ahead, and making sure his men were able to push ahead, made him a favorite of General John J. Pershing’s (1860-1948).

Combat: Meuse-Argonne Offensive↑

Donovan became chief of staff for the 165th Regiment in time for a renewed push in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive in mid-October 1918. The offensive’s objective was to break through the German line at the Kriemhilde Stellung south of Saint-Georges and Landres-et-Saint-Georges, France. The attacking forces were comprised of the 83rd, with Donovan’s 165th as one of its regiments, and the 84th Brigade, commanded by MacArthur. After a day of fighting through deadly German machine guns, artillery, and poison gas, Donovan had gone further than any other American unit. However, this was a problem. Disconnected from the supporting forces, and unaware of their true location, he began to reorganize his men at dawn on 15 October. While racing between groups of soldiers, a bullet ripped into his leg, right below his knee. Nonetheless, he refused to be evacuated while shouting or writing orders to the battalion commanders. When phone lines went dead, he used messengers – to little effect, as enemy fire killed nearly all of them. Without direction from his commanders, Donovan realized his position was untenable and pulled back.

Post-war↑

Pershing decorated Donovan with a second Distinguished Service Cross for his actions that day. The chaplain of the 69th Division, Father Francis Duffy (1871-1932), advocated, after the war, to have Donovan’s decoration upgraded to a Medal of Honor. In 1922, with Pershing as chief of staff, and a new secretary of war, Donovan received the award. He became a successful trust attorney in New York City, but ran unsuccessfully for both lieutenant governor in 1922 and New York governor in 1932, as a Republican candidate. After losing a second time, he avoided elected office but sought to become Roosevelt’s secretary of war in 1940. Instead, Roosevelt sent him on fact-finding trips around Europe where he assessed the ability of the British to hold on after the fall of France.

With war looming, Roosevelt looked for another Republican to put in his team, and, in 1941, appointed Donovan coordinator of information. In June 1942, he created the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and made Donovan its director, despite his lack of intelligence experience. Nevertheless, Roosevelt appreciated the geopolitical assessments Donovan provided and, as a Republican, Donovan would make the war effort more bi-partisan. Donovan instilled his daring and willingness to make his own rules, just like he had done in October 1918, in the OSS. While his superiors often resented his style in both wars, his subordinates loved him for it and much of the secondary literature and primary sources portray him as one of the most inspiring and respected military leaders of the 20th century.

Benjamin F. Jones, Dakota State University

Section Editor: Lon Strauss

Notes

- ↑ Waller, Douglas: Wild Bill Donovan: The Spymaster Who Created the OSS and Modern American Espionage, New York 2011, p. 23.

Selected Bibliography

- Brown, Anthony Cave: Wild Bill Donovan. The last hero, New York 1982: Times Books.

- Dunlop, Richard: Donovan. America's master spy, New York 2014: Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.

- Ford, Corey: Donovan of OSS, Boston 1970: Little, Brown and Company.

- Waller, Douglas C.: Wild Bill Donovan. The spymaster who created the OSS and modern American espionage, New York 2011: Free Press.