Introduction↑

Anton Ivanovich Denikin (1872-1947) has both defenders and critics among the historians writing about his political and military career. The first group see Denikin as a Russian patriot who distinguished himself on the battlefields of the Russo-Japanese War, the First World War and the Russian Civil War. As a leader of the White movement, he actively opposed the “illegal” Bolshevik regime and tried to create a free and powerful Russia. They argue that his writings on the pre-revolutionary Russian army and the civil war contain considered and well-substantiated assessments and interpretations.

His critics underline the “reactionary” politics of the anti-Bolshevik government in southern Russia under Denikin. His army perpetrated mass atrocities and anti-Jewish pogroms. They claim that he made many strategic mistakes, in the military and the political spheres, which helped hasten the defeat of White forces in the south of the country.

Background↑

Anton Denikin was born to a military family (his father rose through the ranks to become major) and raised in the Russian Orthodox faith. He studied first at Lovich Realschule (1890) and later graduated from the Kiev Officer School (1892). He then joined the 2nd Artillery Brigade as a second lieutenant. Three years later, he started studying in the Academy of the General Staff, which he completed with the rank of captain in 1899. However, he only joined the General Staff three years later. He commanded a company of the 183rd Pultusk Infantry Regiment in Poland. Between 1902 and 1904, he served as the senior adjutant of the 2nd Infantry Division and the 2nd Cavalry Corps. Following the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War, he requested a transfer to the army in the field. In the Far East, he served as the head of the 3rd Brigade of the Separate Corps of Border Guards, and then as a staff officer for special commissions in the staff of the 9th and then 8th Army Corps of the Manchurian Army and head of staff of the Baikal Cossack Division under General Paul von Rennenkampf (1854-1918). He was present at the defeat at Mukden. Afterwards, he was appointed head of staff of the Ural-Baikal Integrated Cavalry Division under General Pavel Mishchenko (1853-1918). He conducted raids in the rear of the Japanese army. In recognition of his distinguished service, he was promoted to the rank of colonel (1905).

After the war, Denikin returned to Poland, taking up the post of staff officer for special commissions with the 2nd Cavalry Corps and commanding a battalion of the 228th Khvalynsk Reserve Regiment. In 1906, while on leave, he visited Austria-Hungary, France, Italy, Germany and Switzerland. Afterwards, from 1907 to 1910, he served as head of staff of the 57th Infantry Reserve Brigade, garrisoned in Saratov. He then commanded the 17th Akhangel’sk Infantry Regiment based in Zhitomir from 1910 to 1914.

First World War↑

On the eve of the First World War, he received the rank of general major and served on the staff of the Kiev Military District. At the beginning of the war, he was appointed quartermaster general of the 8th Army under Alekseĭ Alekseevich Brusilov (1853-1926). At his own initiative, he was transferred to a combat unit. He became commander of the 4th Rifle Brigade, later expanded into the 4th Rifle Division. In 1914, he received the St. George Sword and the Order of St. George, 4th Class, for the battles at Gródek and Sambor. In 1915, he was awarded the Order of St. George, 3rd Class, for the military action at Lutovisko and the rank of lieutenant general for taking Lutsk. He took part in the breakthrough at Lutsk during the Brusilov Offensive in 1916, for which he received the St. George’s Cross with Diamonds on which was inscribed “For Twice Liberating Lutsk”. He commanded the 8th Army Corps stationed on the Romanian Front (1916–1917).

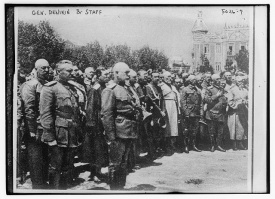

Denikin welcomed the collapse of the Russian monarchy. In March 1917, he was appointed assistant to the head of staff of the supreme commander in chief, General Mikhail Alekseyev (1857-1918); he later became Alekseyev’s head of staff. He viewed the “revolutionary” transformations and “democratisation” of the army negatively, and tried to limit the role of the soldiers’ committees. After Alekseyev’s dismissal, he was appointed commander of the western front (from June 1917) and then south-western front (from August 1917). He was dismissed and arrested for supporting Lavr Georgievich Kornilov’s (1870-1918) rising. During the investigation, he was held with several other generals and officers in Berdichev and then Bykhov. Following the Bolshevik takeover of power, the guards freed him. He escaped to the district of the Don Cossack army, where General Alekseyev had begun forming the Volunteer Army in Novocherkassk. In January 1918, he became head of the 1st Volunteer Division, and later deputy commander of the army under General Kornilov. He fought in the White Volunteer Army’s first and second Kuban campaigns. In April 1918, after Kornilov’s death, he became commander of the Volunteer Army, rising to the position of commander-in-chief when Alekseyev died in October 1918. After the unification of White military forces in January 1919, his title was commander-in-chief of the Armed Forces of Southern Russia. He headed the anti-Bolshevik government in southern Russia, the Special Council, which was primarily made up of military men. It employed republican slogans, but postponed any decision on the future shape of Russia until after the civil war. Following the defeat and retreat of White forces in autumn 1919 and winter 1920, an oppositional group of generals under Petr Nikolaevich Wrangel (1878-1928) developed. The military council of Feodosiia in March 1920 chose Wrangel as the new commander-in-chief. Denikin confirmed this decision and went into retirement.

Post-war↑

The general took his family to Constantinople and then London. In August 1920, he moved to Brussels and in June 1922 to Budapest. After that, he returned to Belgium in 1925, later settling in a suburb of Paris in 1926. He did not take an active role in the political and social life of the Russian emigration, concentrating instead on writing. During the German occupation of France, from 1940 to 1944, he lived in Moussan, in the south of the country and refused to cooperate with the German authorities. He came out in support of the Red Army in the Second World War and against the Russian All-Military Union, which was in favour of working with Nazi Germany. In November 1945, he emigrated to the USA, where he lived for more than two years. He was first buried in Detroit, but, in December 1952, was reinterred in the St. Vladimir Orthodox cemetery in Jackson, New Jersey. In October 2005, the Russian government had the remains of Denikin and his wife transferred to his homeland, where they were reburied in the Donskoi Monastery in Moscow.

Conclusion↑

Denikin was most famous as a military commander in the First World War and a leader of the White movement in southern Russian and Ukraine during the Russian Civil War. In the First World War, he distinguished himself as a commander of a brigade, division and corps, rising to the post of commander of the front. Although he viewed the fall of the Russian monarchy positively, he protested against the “democratisation” of the army and took part in the Kornilov Affair in order to remove the Provisional Government. Denikin reached the height of his fame as the leader of the White movement in southern Russia. All in all, between 1918 and 1919, his army successfully fought against the Soviet regime, capturing large swathes of territory in Ukraine, the Caucasus and southern Russia. As a politician, he envisaged the country developing as a republic and was close to the ideology of the Kadets. The defeat of the White forces forced Denikin to go into retirement, giving up his position to General Wrangel. Denikin’s literary legacy, mainly written in emigration, places him in the first ranks of memoirists and analysts of the history of the Russian army and Russian Civil War. Denikin is commemorated on memorial plaques in several Russian towns, such as Saratov and Feodosiia. The general’s burial monument is a central part of the Memorial to the White Forces in the Donskoi Monastery in Moscow.

Evgenii Vladimirovich Volkov, Southern Urals State University

Section Editors: Yulia Khmelevskaya; Katja Bruisch; Olga Nikonova; Oksana Nagornaja

Translator: Christopher Gilley

Selected Bibliography

- Cherkasov-Georgievskii, V.: General Denikin, Smolensk 1999: Rusich.

- Ipolitov, G. M.: Denikin, Moscow 2006: Molodaia gvardiia.

- Kozlov, A. I.: Anton Ivanovich Denikin. Chelovek, polkovodets, politik, uchenyi (Anton Ivanovich Denikin. Man, commander, politician, scientist), Moskow 2004: Sobranie.

- Lehovich, D.: White against red. The life of general Anton Denikin, New York 1974: Norton.

- Vasilevskiĭ, I. M.: Gen. A. I. Denikin i ego memuary (General A. I. Denikin and his memoirs), Berlin 1924: Aktsionernoe obshchestvo “Nakanune”.