Introduction↑

Death in war overcomes its eschatological dimension and is transfigured, through a process of sacred capitalization, into the highest form of national heroism.[1] The impact of the loss spreads far beyond the moment and geographical location of the conflict, affecting not only the combatants themselves but also society as a whole, emerging as the gravitational center of future processes of remembering.

If we set Portugal’s experience against those of the other nations that took part in the war, the losses suffered by the Portuguese armed forces – some 7,000 men out of 105,544 mobilized on all fronts[2] – may seem comparatively insignificant. However, the absence of consensus around intervention in Europe on the part of one of the continent’s rare republics; the lack of clashes on Portuguese metropolitan soil; the frustration with peace talks and potential rewards, despite the Allied victory; and the political instability that stretched far beyond the conflict, culminating in an authoritarian regime, paint a portrait of a mutilated victory,[3] where any justification falls far short of the sacrifice of life.

The memory of the conflict was shaped by the scale of the tragedy; while it gave rise to heated debate and political battles in the immediate wake of the war, especially regarding the First Republic and its responsibility for the tragedy, it would soon slip into a profound silence. Following the establishment of the Estado Novo (1933), the last leaders of attempts to keep the memory of the conflict alive disappeared from power and from public view.[4]

First World War historiography has long reflected on the direct relationship between the banalization of violence in war and the creeping brutalization of society and politics in the postwar period.[5] This study contributes an analysis of the Portuguese case, whose culture of war[6] failed to correspond to the modern forms promoted by a fascistic culture, as much as the national political situation might indicate the opposite. While one set of studies describes the conflict as provoking a modern rupture in cultural language,[7] Jay Winter argues that the remembering of war hearkens back to a traditional framework.[8]

In light of the threat of rupture imposed by modern war, authorities invested in processes of remembrance, working to create a hegemonic official memory designed to “restore” national order. Under the First Republic, this not-always-peaceful process of remembering the war effort (an effort which rested on an army of forcibly drafted citizens) tended to focus on the dead.[9] This in turn gave rise to an array of practices and representations derived from familiar molds, which representatives of the republic adapted either from Christian traditions or from the historical memory at the foundation of the definition of the modern state.

Here, we provide a brief summary of the politics of memory of the First World War in Portugal. The study limits itself to official memory,[10] which obviously has an interdependent relationship with other forms of memory, as well as the way it may be framed as cultural memory.[11] In light of the interpretive paradigms available to us, we question the nature of the processes by which the Great War was remembered in Portugal.

Commemorations↑

From the very start, the political construction of the memory of the war in Portugal was shrouded in controversy. From the little-hailed arrival of the troops in Lisbon to the fraught undertaking of determining an official day to remember the Great War (April 9, the date of the Battle of the Lys), the process served to bring out a variety of meanings and tensions stemming from the political representation of the war.

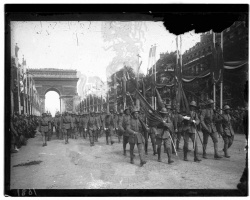

Portugal saw its place among the victorious Allies cemented by its participation in the victory procession through Paris on 14 July 1919. In a sign of harmony with the principles, not only of the victory, but also of the republic itself,[12] official celebrations for that year were concentrated on that date.[13] After 1919, the date faded from view, and remembrance and debate alike came to settle around November 11 and April 9. With a few exceptions, November 11, which marked the end of the conflict, was adopted across the board by the countries involved. In Portugal, the First Republic came to a contentious decision: April 9.

The peak of activities on April 9, the official day to remember the war, came in 1921. It was designated as a national holiday for the first time that year[14] and saw the most significant tribute to the war effort to date, organized by the ministry of war: the ceremony to honor the unknown soldier. The festivities returned in 1924 with the definitive interment of the bodies of unknown soldiers, whose remains were put to rest far from the capital, in the Batalha Monastery. On 9 April 1925, the future protagonists of the military coup of 1926 cried out for change: “Porque o 9 de Abril constituiu uma das mentiras oficiais do nosso Estado Político, responsável único pelo desastre das legiões portuguesas que heroicamente se bateram.”[15] In the absence of widespread support for remembering the war on the date of a defeat, the military dictatorship established in 1926 moved its remembrance activities to Armistice Day. That year, the date was made a national holiday[16] for the first time, kicking off a series of tributes focused on the heroism of the Portuguese armed forces. Remembrance activities on April 9 persisted largely by virtue of the effort of associations which had been involved in the war, such as the Northern Patriotic League (1917-1937), the Great War Monuments Commission (1921-1936), and the Combatants League of the Great War (1924-present).[17]

While the military dictatorship capitalized on the April date to blame the republic for the travails of war, relegating it to a position of failure, António de Oliveira Salazar (1889-1970) went a step further: the war was to be forgotten almost altogether, and commemorations were limited to honoring the dead at cemeteries and the like.[18]

April 9 embodied the range of conflicts that marked the processes of remembrance of the war. Among many other controversies, this choice highlighted a defeat – it was at the Battle of the Lys that the Portuguese Expeditionary Corps suffered the majority of its losses – and focused exclusively on the European front, diminishing attention to interventions in colonial territories. This was not a militarized celebration of victory, but an act of funereal reverence for the dead, in the name of the motherland. A morning mass in the name of the fallen soldiers was followed by a procession, with a children’s choir leading the way toward the monument – a symbolic tomb – where a funeral wreath was laid and the memory of the dead invoked. A minute of silence followed. The songs sung by the children’s choirs paid tribute to the fallen (De Profundis and Libera), peace (Hino da Paz), or historical memory (Hino da Maria da Fonte).

This ceremony, which was derived from traditional forms, took on a new dimension, one inherently associated with the nature of the conflict, allowing the republic to elevate the anonymous heroes from the citizen army to the pantheon of civil religion. April 9 was to produce future war heroes, from the collective (the Minho Brigade, which bore the brunt of losses in battle), to the universal (the unknown soldier). Civic appropriation of Christian funeral liturgies lent the ritual some familiarity. In distancing itself from radical secularization, the regime sought to ward off criticism through its honoring of the dead. According to Daniel Sherman, support for anniversaries such as these rested not on the reasons or events at their core, but the prevailing understanding of what was being commemorated.[19]

A Cemetery↑

In the postwar period, the political exercise of mourning required significant material and symbolic investment; traditional rites were insufficient in light of the sheer number of dead produced by the modern war. From absent bodies to unidentified remains, metaphorical representations sought to overcome the banality of death en masse, transmuting it into a new lexicon where death on the battlefield signified not loss, but valor.[20]

The combination of a mass of dead bodies, some of them unidentifiable, and practical impediments to repatriation led to investment in funeral spaces on the site of the old front. The Portuguese government focused its efforts on creating one major cemetery.

By war’s end, Portuguese soldiers’ bodies had been laid to rest in some 260 cemeteries across France, Germany, Belgium, Holland, England, and Poland. Of a total of some 2,806 victims, around 202 were left unburied or interred in mass graves when identification was not possible. While regulations governing the treatment of remains (burial, identification, and location) dated from 1917, the belated creation of the Portuguese War Graves Commission,[21] which only came about in 1919, meant that the work of gathering the nation’s fallen in a single cemetery stretched on until 1938.

The idea of founding a Portuguese military cemetery at Richebourg l’Avoué arose in 1921, but the design for the space, by the architect Tertuliano de Lacerda Marques (1882-1942), was only finished in 1935.[22] The project was structured around Portuguese symbolism and rested on a British framework, since much of the processes for dealing with bodies were drawn from the rules of the Imperial War Graves Commission. Its 1,831 graves, 238 of which held unknown soldiers, were laid out in four lines. There was a monument at its head and an elaborately sculpted entry arch. The funereal space itself bears the marks of war. Uniform white tombstones, duly identified and marked with crosses, laid out uniformly across the field, served as a guarantee that the dead of this citizen army would be honored equally. The votive altar, sparsely decorated with regional administrative symbols and a coat of arms, was host to prayers enshrining the new heroes of the nation’s civic religion. Closing off the burial ground was an arch decorated by metalworkers specializing in the traditional rendilhado style of filigree and flanked by the Christian and war crosses. The Mediterranean plants distributed across the grounds served to renew the memory of the dead, incorporating them into the life cycle of nature. Metaphors of absence made political mourning concrete, in a strange, tenuously funereal national liturgy that sought to diminish the impact of the multitude of the dead through neutralizing, standard treatment.

Unknown Soldiers↑

With the bodies of the fallen buried far from home, it fell to those responsible for the loss to make amends for this absence by returning the victims to their families in the form of simulacra which were symbolic or material to a greater or lesser extent. The abstraction of a ritual held at a distance aggravated the recognition of their sacrifice, which was exacerbated in the Portuguese case by the absence of any battles on national soil.

The unknown soldier represented the peak of the official ceremonies of remembrance for the Great War. The ritualization of selection, transportation, and entombment became a common practice in the war cultures of the countries involved, a sign of the centrality of the cult of the dead at war’s end.[23] In response to the impersonal nature of a conflict of this scope, the anonymous hero was made to exemplify the nation’s best qualities.

In Portugal, two unknown soldiers in particular, one from the European front and another who fell in Mozambique, were honored on 9 April 1921 and buried three years later at the Batalha Monastery. The ministry of war organized this, the most international of all the events organized to remember the Great War. The ceremony encompassed the arrival of the unknown soldiers in Lisbon, a tribute at the Congressional Palace, a parade down the main streets of the capital, and finally the laying to rest of the two bodies at the monastery.[24]

Despite its grandiose scale, which lent the ceremony broad popular support, and the presence of leading figures in the national and international war effort, the form, timing, and site of the event sparked another series of controversies. The need for two unknown soldiers was intrinsically associated with a search for consensus, which the First Republic had in fact been unable to attain at the time of mobilization. While the population rallied around the defense of the colonies, the same was not true of intervention on the European front. As we have seen, the date of the defeat, April 9, enshrines the funereal aspect of these processes of remembrance, which are funneled into the patriotic transformation of the dead into heroes. The Batalha Monastery, the site of their interment, was yet another source of controversy.[25] The fact that the unknown soldier was laid to rest in a medieval gothic monastery speaks to a prevailing lack of confidence in the republic’s ability to deposit its heroes in its own pantheon. Far from the capital, the monastery bore a variety of meanings that were fundamentally inseparable from the Battle of Aljubarrota – not only did the clash seal Portugal’s victory over Spain, a country that had remained neutral during the Great War and in relation to which Portugal sought to distinguish itself, but it had also provided a hero of growing importance in national historical memory. Nuno Álvares Pereira (1360-1431), beatified in January 1918, became a focal point for conciliatory political visions that encompassed a broad range of visions in the republic.[26]

While the placement of the unknown soldier at Westminster Abbey reflected the unique position of the Anglican Church in the United Kingdom, in Portugal the choice of a religious space spoke to the state of the republic, which grasped at the venerable traditions of the Catholic Church and the monarchy to legitimate its memorials and cement new alliances.

Monuments↑

The emergence of monuments in the countries that participated in the war stemmed from the need to overcome the absence of bodies produced by the circumstances of modern war, transferring that absence into a material representation.[27] These monuments – numbering over a hundred across Portuguese territory – represent the peak of the First Republic’s project of remembrance.[28] Despite its major public impact, the initiative was not solely a government project, but rather the result of heated negotiations between the state, grieving communities,[29] local authorities and associations engaged with the cause, especially the Northern Patriotic League, which proposed the adoption of the padrão model of monuments that soon spread across the country.

Calling this a monument to the dead of the Great War signified the First Republic’s choice to pay tribute to the fallen soldiers from the national army based on the draft. In this sense, the majority of monuments in Portugal constructed over the 1920s have a civic character. While the most common inscription is “To the dead of the Great War,” their placement in public squares or parks reinforces their civic essence.

To understand the impact of the whole array as the vehicle of a memorial project and a propaganda tool, cross-referenced analyses have taken location, epigraphs, and iconography into account to group the monuments under categories such as “civic,” “patriotic,” and, in a few rare cases, “victorious” and “funereal.”[30]

Iconography serves to lend the monument nearly the sum total of its meaning. While sculptors theoretically enjoyed a degree of freedom, in practice their autonomy was limited and bowed to public scrutiny. The most common memorial model followed the suggestion of the Northern Patriotic League, with the first inaugurated in 1924.[31] The padrão – a stone column crowned by a Christian cross or an armillary sphere[32] – was an easy out for local authorities. It responded to the needs of the grieving community as well as the desire to politically perpetuate historical memory, in an allusion to the “Portuguese discoveries”. The second most common type, which may be the most transnational, is the Serrano.[33] Standing in uniform, with or without a weapon, in a resting position, these statues hardly represented a militaristic evocation of victory.

These civic projects were soon joined by patriotic works and, although quite rarely, victorious ones: true emblems of the republic’s aspiration to claim the political spoils of victory. The tone was set by the allegories, since most were placed in public squares without any special inscription: this is true of the rare victorious sculptures – represented by wings, palms, swords, or laurel wreaths – and the more common nationalistic variety. The latter varied from Greco-Roman or feudal compositions, as in the case of the National Monument in Lisbon[34] (which took eleven years to complete), to the figure of the nation depicted in São João da Madeira.[35] Hearkening back to a preindustrial past not yet contaminated by war, the use of allegories seeks to avoid a critical tone and presents humanized female bodies, as seen in three separate matres dolorosae.[36]

While the monuments to the dead of the Great War emerged and spread quickly, they remained conservative, in that they essentially perpetuated national historical memory. This much becomes clear from the consensus around the use of the padrão, in an allusion to the discoveries – an omnipresent element of the republican nationalist liturgy. It would be misleading to attribute the few projects that include modernist features or were built on a gigantic scale to the initiative of the Estado Novo. Memorials such as those in São João da Madeira, Abrantes, Luanda, or Lourenço Marques – with special emphasis on the last two, as they were carried out by the Great War Monuments Commission – sprang from objectives devised under the First Republic and the need to symbolically reinforce the Portuguese presence in the colonies in the postwar period.[37] The vast majority of the monuments had no visible fascist connotation;[38] they were largely erected in the 1920s in response to the many desires of official entities, local authorities, grieving communities, and, above all, the aims of the First Republic.

Possible Conclusions↑

In Portugal, the remembrance of this war was not put to the service of a political, social, and cultural rupture. It was framed by phenomena of cultural memory, in a syncretic combination of political and religious formulas mustered to help overcome the traumatic experience of war. Adapted to the extraordinarily new solutions called for by the culture of war, the politics of memory, as championed by the First Republic, focused on honoring those who died serving in the citizen army. In this sense, the regime turned to familial and traditional molds, whether drawn from the Christian tradition or public art from the turn of the 20th century, in order to perpetuating its status as the legitimate head of the nation. The memory of the war persisted in spite of the silence imposed from the mid-1930s onward as to its republican essence. The heroes who fell in the name of the nation, however, were unable to secure the political perpetuation of the First Republic.

Silvia Correia, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro

Section Editor: Filipe Ribeiro de Meneses

Translator: Flora Thomson-DeVeaux

Notes

- ↑ For a more detailed study of World War I memory policies, see Correia, Silvia: Celebrating Victory on a Day of Defeat. Commemorating the First World War in Portugal, 1918-1933, in: European Review of History 24 (2016), pp. 108-130; Correia, Silvia: Entre a morte e o mito. Políticas da memória da I Guerra Mundial em Portugal (1918-1933) [Between Death and Myth. Politics of Memory of World War I in Portugal (1918-1933)], Lisbon 2015; Correia, Silvia: Death and Politics. The Unknown Warrior at the Center of the Political Memory of the First World War in Portugal, in: e-Journal of Portuguese History 11 (2013), pp. 7-29.

- ↑ Afonso, Aniceto: Portugal e a Guerra nas Colónias [Portugal and the War in the Colonies], in: Rosas, Fernando/Rollo, Fernanda (eds.): História da I República [History of the First Republic], Lisbon 2009, 287-299.

- ↑ Gibelli, António: La Grande Guerra degli Italiani [The Great War of the Italian], Milan 1998. The study of the Portuguese case took special account of Italian, due to the political resemblance.

- ↑ On the relation between the representation of the war and political change, see Correia, Silvia: The Veterans’ Movement and First World War Memory in Portugal (1918-33). Between the Republic and Dictatorship, in: European Review of History 19 (2012), pp. 531-551; Meneses, Filipe Ribeiro de: Salazar, the Portuguese Army and Great War Commemoration, 1936-45, in: Contemporary European History 20/04 (2011), pp. 405-418; Meneses, Filipe Ribeiro de: Portugal 1914-1926. From the First World War to Military Dictatorship, Bristol 2004.

- ↑ See, among others, Isnenghi, Mario: Il mito della Grande Guerra. da Da Marinetti a Malaparte [O mito da Grande Guerra: de Marinetti a Malaparte], Bari 1970; Mosse, George L.: Fallen Soldiers. Reshaping the Memory of the World Wars, Oxford 1990.

- ↑ Annette Becker and Audoin-Rouzeau, quoted in Lemoine, Thierry: Culture(s) de guerre, évolution d’un concept, in: van Ypersele, Laurence (ed.): Questions d’histoire contemporaine. Conflits, mémoires et identités, Paris 2006.

- ↑ See, among others, Fussell, Paul: The Great War and Modern Memory, New York et al. 1975; Eksteins, Modris: Rites of Spring. The Great War and the Birth of the Modern Age, Boston 1989.

- ↑ Winter, Jay: Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning. The Great War in European Cultural History, Cambridge 1995; Winter, Jay: Remembering War. The Great War Between Memory and History in the Twentieth Century, London et al. 2006. Winter’s view is central to my understanding of the remembrance of war.

- ↑ The French case is the one to which the Portuguese are closer. The analysis started from Prost’s work: Prost, Antoine: In the Wake of War. “Les Anciens Combattants” and French Society, 1914-39, Oxford 1992; Prost, Antoine: Les anciens combattants et la société française 1914-1939, 3 volumes, Paris 1977.

- ↑ Frank, Robert: La mémoire et l’histoire, issued by Institut d’histoire du temps présent, online: http://www.ihtp.cnrs.fr/spip.php%3Farticle233&lang=fr.html (retrieved: 26 January 2010).

- ↑ Assmann, Jan: O que é a “memória cultural”? [What is “Cultural Memory”?], in: Alves, F. / Soares, L. A. / Rodrigues, C. V.: Estudos de Memória. Teoria e análise cultural [Memory Studies. Theory and Cultural Analysis], Famalicão 2016, pp. 87-116.

- ↑ Commemorations reveal, once again, similarities to the French case. See, for example, Dalisson, Rémi: La célébration du 11 novembre ou l'enjeu de la mémoire combattante dans l'entre-deux-guerres (1918-1939), Guerres mondiales et conflits contemporaines, in: Revue d'histoire 192 (1998), pp. 5-24; Becker, Annette: Du 14 juillet 1919 au 11 novembre 1920 mort, où est ta victoire? in: Vingtième Siècle. Revue d'histoire 49/1 (1996), pp. 31-44.

- ↑ Ilustração Portuguesa, Lisbon, 4 August 1919, p. 86.

- ↑ Law n.º 1:140, Diário do Governo (Lisbon), I Series, n.º 20, 6 April 1921.

- ↑ “for the 9th of April was one of the official lies of our political state, the sole party responsible for the fate of the Portuguese legions which so heroically fell.” O Século, Lisbon, 9 April 1925, p. 1.

- ↑ Decree n.º 12:635, Diário do Governo (Lisbon), I Series, n.º 252, 10 November 1926.

- ↑ As a result of governmental intervention, the Combatants League of the Great War suffered structural changes in 1934 and lost autonomy. See Correia, Silvia: The Veterans’ Movement and First World War Memory in Portugal (1918-33). Between the Republic and Dictatorship, in: European Review of History 19 (2012), pp. 531-551.

- ↑ Correia, Silvia: Celebrating victory on a day of defeat. Commemorating the First World War in Portugal, 1918-1933, in: European Review of History 24/1, 2017, pp. 108-130.

- ↑ Sherman, Daniel: The Construction of Memory in Interwar France, Chicago 1999, pp. 9-10.

- ↑ On the centrality of the cult of the dead, among others, see Gibelli, António: La Grande Guerra degli Italiani, Milan 1998; Becker, Annette / Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane: 14-18 Retrouver la Guerre, Paris 2000; Mosse, Fallen Soldiers 1990; Winter, Sites of Memory 1995.

- ↑ AHM, 1 Div., 35 Sec., Box 1505, Instructions on Burial, France 1917. The Portuguese War Graves Commission organized plots in other cemeteries in Europe and plots and ossuaries in Portuguese territory that were similar to European models.

- ↑ AHM, FO, 006, L, 20, Box 778, Portuguese Cemetery of Richebourg l'Avoué, 12 July 1935.

- ↑ Mosse, Fallen Soldiers 1990.

- ↑ Correia, Silvia: Death and politics. The unknown warrior at the center of the political memory of the First World War in Portugal, in: E-Journal of Portuguese History 11/2, 2013, pp. 7-29.

- ↑ Diário da Câmara dos Deputados (Lisbon), 13 June 1922.

- ↑ Leal, Ernesto Castro: Nação e nacionalismos. A Cruzada Nacional de D. Nuno Álvares Pereira e as origens do Estado Novo (1918-1938) [Nation and Nationalisms. The National Crusade of D. Nuno Álvares Pereira and the Origins of Estado Novo (1918-1938)], Lisbon 1999.

- ↑ Sherman, The Construction of Memory 1999, p. 100.

- ↑ Correia, Silvia: Forgotten Places of Memory. First World War Memorials in Portugal, 1919-1933, in: Niżnik, Józef (ed.): Twentieth Century Wars in European Memory, London 2013, pp. 37-66.

- ↑ Winter, Sites of Memory 1995.

- ↑ For an analysis of monuments, for example see Inglis, K. S.: War Memorials. Ten Questions for Historians, in: Guerres Mondiales et Conflits Contemporains 178 (1995), pp. 5-22; Prost, Antoine: Mémoires Locales et Mémoires Nationales. Les monuments de 1914-1918 en France, in: Guerres Mondiales et Conflits Contemporains 178 (1995), pp. 5-94; Canal, Claudio: La retorica della morte. I monumenti ai caduti della Grande guerra, in: Rivista di storia contemporanea, 4 (1982), pp. 659-669; Becker, Annette: Les Monuments aux morts. Mémoire de la Grande Guerre, Paris 1991.

- ↑ A Guerra, Lisbon, 4/44, August 1929, p. 4.

- ↑ On Portuguese art, see Saial, Joaquim: Estatuária portuguesa dos anos 30 [Portuguese statuary of the 1930s] (1926-1940), Mirandela 1991; França, José-Augusto: O modernismo na Arte Portuguesa [Modernism in Portuguese Art], Lisbon 1979; Pereira, José Fernandes: Dicionário de Escultura Portuguesa [Portuguese Sculpture Dictionary], Lisbon 2005; França, José- Augusto: A arte e Portugal no século XX [Art and Portugal in the twentieth century], Lisbon 1974. .

- ↑ Serrano is an informal term for Portuguese First World War soldiers, which means mountain man.

- ↑ Correia, Silvia: Forgotten places of memory. First World War memorials in Portugal, 1919-1933, in: Niżnik, Józef (ed.): Twentieth century wars in European memory, Frankfurt a. M. 2013: P. Lang, pp. 37- 66.

- ↑ Examples of monuments that use the allegory to the motherland are Abrantes (Rui Roque Gameiro 28 May 1955); Lisbon (Maximiano Alves, 21 November 1931); Lourenço Marques, nowadays Maputo (Rui Roque Gameiro, 29 October 1935); São João da Madeira (Henrique Moreira, 11 November 1937); Soure (Francisco dos Santos, 25 June 1934). See Great War Monuments Commission: Relatório Geral da Comissão (1921-1936). Padrões da Grande Guerra. Consagração do esforço militar de Portugal 1914-18 [General Report of the Commission (1921-1936). Patterns of the Great War. Consecration of the Military Effort of Portugal 1914-18], Lisbon 1936.

- ↑ The three are in Cascais (Simões de Almeida Sobrinho), Oporto (João da Silva) and Tondela (Branca Alarcão).

- ↑ See O Século, Lisbon, 18 March 1924, p. 1, e. 5; O Século, Lisbon, 7 November 1928, p. 2.

- ↑ See Dogliani, Patricia: Les monuments aux morts de la grande guerre en Italie, in: Guerres mondiales et conflits contemporains 167 (1992), pp. 87-94 to understand the differences between the Portuguese and Italian cases.

Selected Bibliography

- Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane / Becker, Annette: 14-18. Retrouver la guerre, Paris 2000: Gallimard.

- Correia, Silvia: Death and politics. The unknown warrior at the center of the political memory of the First World War in Portugal, in: E-Journal of Portuguese History 11/2, 2013, pp. 7-29.

- Correia, Silvia: Entre heróis e mortos. Políticas da memória da I Guerra Mundial em Portugal (1918-1933) (Between death and myth. Politics of the memory of World War I in Portugal (1918-1933)), Lisbon 2015: Círculo de Leitores.

- Correia, Silvia: Celebrating victory on a day of defeat. Commemorating the First World War in Portugal, 1918-1933, in: European Review of History 24/1, 2017, pp. 108-130.

- Correia, Silvia: Forgotten places of memory. First World War memorials in Portugal, 1919-1933, in: Niżnik, Józef (ed.): Twentieth century wars in European memory, Frankfurt a. M. 2013: P. Lang, pp. 37-66.

- Fussell, Paul: The Great War and modern memory, Oxford 2013: Oxford University Press.

- Isnenghi, Mario: Il mito della grande guerra. Da Marinetti a Malaparte, Bari 1970: Laterza.

- Meneses, Filipe Ribeiro de: Salazar, the Portuguese army and Great War commemoration, 1936-45, in: Contemporary European History 20/4, 2011, pp. 405-418.

- Meneses, Filipe Ribeiro de: Portugal 1914-1926. From the First World War to military dictatorship, Bristol 2004: Hiplam.

- Mosse, George L.: Fallen soldiers. Reshaping the memory of the world wars, New York 1990: Oxford University Press.

- Prost, Antoine: Les anciens combattants et la société française, 1914-1939, 3 volumes, Paris 1977: Presses de la Fondation nationale des sciences politiques.

- Teixeira, Nuno Severiano: O poder e a guerra, 1914-1918. Objectivos nacionais e estratégias políticas na entrada de Portugal na Grande Guerra (Power and war, 1914-1918. National objectives and political strategies of Portugal’s participation in the Great War), Lisbon 1996: Editorial Estampa.

- Winter, Jay: Remembering war. The Great War between memory and history in the twentieth century, New Haven 2006: Yale University Press.

- Winter, Jay: Sites of memory, sites of mourning. The Great War in European cultural history, Cambridge 2000: Cambridge University Press.

- Winter, Jay / Prost, Antoine: The Great War in history. Debates and controversies, 1914 to the present, Cambridge; New York 2005: Cambridge University Press.