Introduction↑

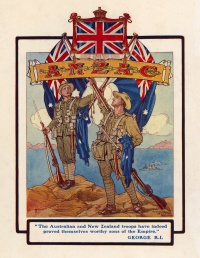

The memory of the First World War has played a remarkably prominent role in Australian political culture over the past century. One of the war’s most enduring legacies was a mythic representation of the Australian soldier in the form of the Anzac (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) legend. Known also as the Anzac myth, Anzac spirit or simply Anzac, this representation of the citizen-in-arms was soon entrenched as the foundational narrative of Australian nationalism, even though many Australians identified strongly with the British Empire of which Australia was then part. In the decades that followed there were profound changes in the framing of Australian nationalism, radical changes in the composition of Australia society and often savage critiques of Anzac, particularly in the 1960s. However, the legend retained its function, as many politicians and the popular media put it today, of enshrining "what it means to be Australian".

The Anzac Legend↑

The origins of the Anzac legend lie in the landing of the 1st Division of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) on the Gallipoli peninsula on 25 April 1915. Like the wider campaign, this operation failed to achieve its strategic objectives. However, the performance of the Australian troops was reported euphorically by two war correspondents, the British journalist Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett (1881-1931) and the Australian journalist Charles Bean (1879-1968). Both these men, one of whom had landed with the troops, declared that Australian soldiers had displayed remarkable courage and resourcefulness, and performed extraordinary physical feats as they scaled the heights above the landing beach at Ari Burnu (later known as Anzac Cove).[1] As the Gallipoli campaign settled into a frustrating stalemate, the image of Australians clinging tenaciously to the precipitous cliffs, only metres from enemy trenches, gained a hold on the cultural imagination of Australians at home. Within weeks the Gallipoli landing was being described as the "birth of the nation".

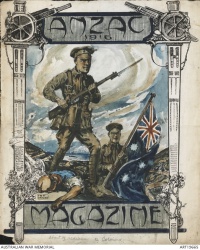

This heroic narrative was soon embedded in local and national commemorative practices through a complex intermingling of official and vernacular memory making. In April 1916 the first anniversary of the landing was marked by a service at Westminster Abbey in London, attended by the British monarch and a galaxy of military and political leaders. Imperial authorities, it seemed, saw the anniversary as a chance to acknowledge the contribution of Dominion troops – New Zealanders, too, had played a significant role at Gallipoli – while salvaging something positive for their own population from the dismal Gallipoli campaign.[2] In Australia, meanwhile, ceremonies across the nation at the local and state level celebrated the Anzacs’ feats while also providing a public sphere for the expression of grief over the recently bereaved. Government and loyalist organizations also exploited the occasion to recruit volunteers to replace those men lost at Gallipoli. Although Anzac Day commemorations in the later years of the war took place on a lesser scale, they continued to serve these multiple and, at times, contradictory purposes.[3]

In the years that followed the First World War the valorising narrative of the Australian soldier continued to be promoted by the conservative press, loyalist politicians and, most especially, by Bean. In his official histories of the war, published from 1921 on, Bean articulated a powerful vision of the Australian soldier as the citizen-in-arms. The men of the AIF, he argued, made natural and superlative soldiers. Although all of them were volunteers (the Australian government failed to win two referenda aimed at introducing conscription in 1916 and 1917), as civilians their lives had been shaped by experience of the bush (Australia’s largely eucalyptus landscape which acquired deep cultural overtones in the Australian imagination in the late 19th century). This physical environment, together with the strongly egalitarian ethos of Australian democracy, ensured that AIF men were naturally independent in spirit, questioning of mindless authority, ruggedly individualistic when it came to military discipline, and utterly committed to "mateship" (or comradeship) during battle. It was these qualities, Bean argued, that accounted for the AIF’s outstanding performance at Gallipoli and later, on the Western Front.

Scholars have debated how much of the Anzac legend was historically accurate[4] (Australia, for example, was a highly urbanized society even in 1914), but this is not the point. Like all myths, the Anzac legend gained traction because it resonated with the needs and values of both individuals and dominant elites. This heroic narrative invested with meaning the more than 61,000 war deaths that stemmed from a population of fewer than 5 million. In addition, the legend provided the conservative political forces, which dominated federal politics from 1917 on, with a means of validating the war and the British imperial cause for which so many Australians had fought and died. Although Anzac articulated a sense of new national consciousness and pride in Australia’s war effort, this nationalism continued to be positioned, at least during the interwar period, within a wider frame of imperial loyalty.[5] Many of the war memorials which were erected by communities throughout Australia in the war and post-war years, therefore, spoke of sacrifice for king and empire as much as for country or Australia.[6]

It is clear that this engagement with the Anzac legend and the associated rituals of Anzac Day was not universal across Australian society. The nation had been left profoundly divided by the political disputes of the war, with the labour movement and Catholics (some 22 percent of the population and many of them of Irish extraction) being demonised as "disloyal" because of their opposition to conscription and their calls for a negotiated peace in 1917-18.[7] Sectarianism shaped memories of the war in the 1920s and 1930s in ways which have not yet been fully explored. Yet by 1927 Anzac Day was a public holiday in all states of the Commonwealth; and 25 April was widely recognised as the national day.

The Second World War and its Aftermath↑

Hence, by the time Australia entered the Second World War on 3 September 1939 Anzac was the seemingly natural frame of memory within which to position the experience of the new war. The all-volunteer expeditionary force, which served initially in the Middle East and then in the Asia-Pacific region, was named the 2nd AIF. Its constituent battalions were assigned the number two as a prefix (for example, 2/21st Battalion). Moreover, press cartoons and other media depicted the soldiers of 1939-45 as heirs to the men of 1914-18, as many of them literally were. Carrying the torch of their fathers, the new generation of soldiers would be judged by the standards that the original Anzacs had set. So dominant was this discourse that Australians who were taken prisoner-of-war by the Japanese in 1941-42 strove, in their later accounts of captivity, to construct themselves as Anzacs. Conscious that they might be stigmatized by defeat and surrender, they claimed that they had manifested in the prison camps of Asia the Anzac qualities of resourcefulness, survival against the odds and mateship.[8]

Hence, nothing that occurred during the Second World War, with the possible exception of the fighting on the Kokoda Track in Papua in mid to late 1942, challenged the centrality of Gallipoli and the rituals of Anzac Day. But within fifteen years this dominance was under assault. One of its most public champions, the Returned Sailors’ Soldiers’ and Airmen’s Imperial League of Australia (RSSAILA) (now the Returned and Services League) was a deeply conservative organization, which fiercely guarded the benefits and entitlements of returned soldiers. By the early 1960s it was under attack for its strident support for Cold War defence policies. Anzac Day, meanwhile, became associated – most notably in Alan Seymour’s (1927-2015) play "The One Day of the Year" – with veterans drinking themselves into a stupor after the morning march through the city streets. The growing hostility to Anzac was strengthened by the use of selective conscription for the Vietnam War, which polarised Australia almost as deeply as had the conscription debates of 1916 and 1917. Finally, the student protests and the rise of second-wave feminism fuelled the perception that Anzac was militaristic, misogynist and anachronistic. By the early 1970s, then, some observers assumed that the rituals of Anzac would fade away as the veterans of the two World Wars aged and died.[9]

The Memory Boom↑

But it proved not to be so. To the surprise of its critics, Anzac and the wider memory of the First World War enjoyed a remarkable revival with the onset of what Jay Winter has called the "second generation of memory" in the last quarter of the 20th century.[10] The reasons for this phenomenon, which was global as well as Australian, are complex, and the subject of ongoing debate.[11] Globally, the "turn to the past" was fuelled by a mix of factors, some of which were: the ageing of eyewitnesses to World War II and the Holocaust; the unfreezing of memories with the end of the ideological rigidity of the Cold War; the growth of identity politics as globalisation and neoliberal economics eroded the traditional legitimacy of the state; the pervasive fin de siècle mood at the end of the 20th century and the second millennium; and the growing fascination with the past and family history in an age where, in the West at least, formal religion and its promise of an afterlife was declining.

Not all of these variables were evident in Australia, but the growth in war memory was nonetheless phenomenal. From the early 1990s on, there was an explosion of commemorative activities at both the government and sub-state level. These covered all conflicts in which Australians had participated in the 20th century, as the politics of recognition led group after group to claim that their war service had been "forgotten". But Gallipoli and the associated Anzac legend were at the heart of this revivified memory of war. Peter Weir’s 1981 film Gallipoli, which culminated with the death of the young hero in the suicidal charge at the Nek in August 1915, was profoundly influential.[12] Constructing the soldier as a victim as much as warrior – as did so much of the war memory of the late 20th century – it socialized successive generations into a mythic memory of Gallipoli and the Australian citizen soldier.

Even more important was the role of Australian governments of both political persuasions, who appropriated the memory of the war to shape Australian nationalism and national identity to suit their political agenda. In retrospect, 1990 seems something of a marker. This was the year of the first officially funded "pilgrimage" of veterans to Gallipoli, a journey led by the Labor Prime Minister Bob Hawke to commemorate the seventy-fifth anniversary of the landing. In contrast, in 1965 the Liberal (conservative) government of Sir Robert Menzies (1894-1978) had refused to fund the pilgrimage being organised by the RSSAILA to mark the fiftieth anniversary. Hawke’s successor Paul Keating continued the official momentum, though coming from an Irish-Catholic background, Keating shifted the focus of commemoration from the First World War – a conflict which he argued cast Australians as lackeys to British imperialism – to the Asia-Pacific war of 1941-45, when Australians unequivocally defended their national sovereignty.

The First World War returned to a more central – though not exclusive – role in national commemoration with the coming to power in 1996 of the Liberal John Howard. Howard’s father and grandfather had both served on the Western Front, and during his time in office (1996-2007) a wave of commemorative activity and memorial building was funded: not just in France, but in Thailand, Borneo, Papua New Guinea, the United Kingdom and along the national mall of commemoration, Anzac Parade in Canberra (to name only the most important). The commemorative calendar expanded to include anniversaries of battles not just on the half- or quarter-century, as had been the practice in the past, but every five or fewer years. Meanwhile the Australian War Memorial (the national museum and memorial to the war dead) was significantly expanded, while a dedicated Commemorations Branch of the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) was funded to organize and invent countless ritual occasions for politicians, veterans and their families, and to develop educational materials and programs aimed at socializing younger Australian into the authorized narrative of Anzac. Increasingly the Anzac spirit was invoked, not just in war commemoration but also at sporting events and during natural disasters, as enshrining the qualities of courage, endurance, sacrifice and mateship to which all Australians should aspire.

Whether all this represented a deliberate top-down manipulation of the Australian public by the state has been debated. In 2010 historians Marilyn Lake, Henry Reynolds and their colleagues condemned the militarization of Australian history by the DVA and other official agencies[13]. This, they claimed, has eclipsed alternative narratives of the nation’s past, such as the early establishment of democratic institutions and the pre-1914 record of social innovation. Certainly the Australian state has invested enormous resources for some twenty-five years in promoting the rituals of Anzac at home and abroad. With the aid of a populist media, it has ensured that the Anzac legend has acquired the status of a hegemonic discourse that is assumed to be natural and incontestable by significant sections of the Australian public.

The motives of these elites in thus promulgating the legend have again been debated. Mark McKenna has argued that Labor leaders of the early 1990s reinvented Anzac Day as "the" national day because Australia Day, 26 January, was irredeemably tainted by its association with the dispossession of Australia’s indigenous peoples (it celebrates the date on which the British First Fleet arrived in 1788).[14] Labor and Liberal governments alike have also exploited Anzac to neutralize dissent about the legitimacy of the conflicts to which the Australian Defence Force is now being deployed. In 2003, for example, when the majority of the population opposed the government’s decision to commit Australian forces to Iraq, Prime Minister Howard depicted these forces as heirs to the Anzac legend. As revered members of this tradition, he claimed, they should not be attacked, as Vietnam veterans had been vilified in the 1960s and 1970s, for serving in an unpopular war.[15]

The agency of the Australian state in the war memory boom is therefore indisputable. However, the resurgence of Anzac cannot be explained exclusively in terms of interventions by governments and their officials. As is now axiomatic in memory studies, the formation of memory is manifest at multiple levels in any society and each domain is interrelated and constitutive of each other. Hence it seems clear that the official construction of Anzac has resonated with many Australians for whom it constitutes a way of belonging to the imagined community of the nation. Attendances at Anzac Day ceremonies in Australia, France and most notably Gallipoli grew significantly between 1995 and 2015, a fact that perhaps owes something also to the enthusiastic reporting of such events by the mainstream media. Moreover, in some notable cases, such as the exhumation and reburial of the missing whose graves were discovered at Fromelles on the Western Front in 2009, it has been individuals who have initiated commemorative activities from the bottom up, forcing the hand of a sometimes reluctant government.[16] Finally, the wider Western appetite for genealogy has also been manifest in Australia. With the aid of new digital databases of the military personnel,[17] descendants of war veterans rush to position their family histories within the wider national narrative of war.

The First World War Centenary↑

There was therefore never any question that Australia’s commemoration of the centenary of the First World War would be huge. Planning started early with the federal government creating two national commissions in 2010-2011 to consult with the public and recommend a commemorative program. Significantly, these endorsed the concept of "A Century of Service": that is, the commemorations of 2014-2018 should extend beyond the key dates in the First World War (Gallipoli, Pozières and the battles of 1918) to cover significant anniversaries of other 20th-century conflicts which fell in this period (namely, seventieth anniversaries of the Second World War and fiftieth of the Vietnam War).[18]

Soon the federal government was committed to a massive program of commemoration. To name only a few of a multitude of events in 2014-2015: the departure of the first convoy of Australians and New Zealanders from Albany, Western Australia in late 1914 was marked by the opening of a national Anzac interpretative centre in that town; the Australian War Memorial was granted 28.7 million dollars to refurbish its First World War gallery and restore its historic battle dioramas; 125,000 dollars was made available to each of the 150 federal electorates for local grants approved by the Department of Veterans’ Affairs;[19] and over 4 million dollars was allocated to an Anzac Centenary Arts and Culture fund to support projects conveying themes and stories about Australians’ experiences of war. Overseas, work proceeded on the development of the Australian Remembrance Trail along the Western Front, a kind of Anzac "stations of the cross" stretching from Bellinglese on the former Hindenburg Line, France, to Iper (Ypres), Belgium.[20] A further 100 million dollars has been allocated to a new interpretative centre, named after the commander of the First World War Australian Corps, Sir John Monash (1865-1931), at the French town of Villers-Bretonneux.[21] This was the site of a famed counterattack which drove the Germans from the town on 24 and 25 April 1918; and of the Australian national memorial on the Western Front which was unveiled in 1938.

Inevitably, the high point of this commemorative orgy was the centenary of the Gallipoli landing. Who would attend this historic event? Since only 10,500 people could be accommodated at the rather confined site, and only 8,000 of these could be Australian – to allow New Zealanders and other stakeholders a place – the government chose to conduct a national ballot for tickets. This had considerable potential for dispute but it proceeded with little controversy. However, the commercialization of Anzac that accompanied the centenary was more contested. Initially little attention was paid to the Australian War Memorial’s array of commodities bearing their centenary slogan, "Their Spirit Our Pride", though its being in receipt of sponsorship from defence companies did cause something of a minor flurry. The mushrooming of Gallipoli experiences – cruise trips to Turkey, battlefield tours and family events such as "Camp Gallipoli" – also proceeded unhindered. But then the grocery chain Woolworths launched an advertising campaign featuring a First World War soldier’s face set against the banner "Lest we Forget Anzac 1915-2015" and the slogan "Fresh in our Memories". This play on the supermarket’s marketing brand, "The Fresh Food People" was condemned as an abuse of the semi-sacred word Anzac, which since 1920 had been protected by legislation. In damage control the Minister for Veterans’ Affairs declared the advertising inappropriate and Woolworths withdrew the campaign.[22]

Meanwhile the question was posed as to whether the Anzac commemorations resonated with the culturally diverse communities that now constitute at least a quarter of Australia’s population.[23] Anzac in its original incarnation was a narrative about white men, and official agencies were conscious of the need to make the commemoration of the First World War more inclusive. The defence service of more than 800 indigenous Australians who served in 1914-1918 (even when they lacked citizen status) was therefore celebrated, while prominence was given to "ethnic" Anzacs, such as the half-Chinese William Sing (1886-1943) who gained notoriety as a sniper at Gallipoli.[24] But the guidelines of the Gallipoli centenary grants to the federal electorates were so traditional that they had the effect of consolidating Anglo-Celtic narratives at the local level in that they involved projects such as the repair of existing war memorials or the writing of local histories of 1914-1918.

As 25 April 2015 approached, there were some inklings of possible commemoration fatigue. The commercially produced mini-series Gallipoli, aired on free-to-air television in March 2015, was a ratings failure. The blog and other commentary that followed[25] condemned the infuriating number of advertisements, the bad timing (Monday mid-evening), and, most significantly, the commercial exploitation and overexposure of the story of Gallipoli. We know the ending; so why tell the story again, particularly when Peter Weir had done it so well?

All of these debates were, however, silenced by the crescendo of media excitement around 25 April 2015. The media issued souvenir wraparound editions and provided blanket coverage of the Anzac Day rituals in Australia, Turkey and France. The cross-generational transmission of the memory of the Anzacs, from Gallipoli to Afghanistan, was a popular theme; while the Anzac Day ceremonies themselves consciously reconciled the old with the new – manifesting a flexibility that goes some way to explaining the legend’s extraordinary resilience as a signifier of national identity. The Australian War Memorial, which has consistently refused to embrace "frontier wars" (that is, violent confrontations between white settlers and indigenous peoples) as part of Australia’s military history, opened the national Anzac Day dawn ceremony with a didgeridoo being played from its parapet. Young women meanwhile featured prominently in dawn services here and elsewhere, speaking to a 21st century version of the Anzac legend that is supposedly gender-neutral.

The official message delivered by senior politicians and defence personnel across the nation and abroad also spoke clearly to the values of the present. Prime Minister Tony Abbott, addressing the Gallipoli dawn service, claimed that "we are here on Gallipoli, because we believe that the Anzacs represented Australians at our best". Gallipoli was invoked as the legitimation of not just the Second World War, Korea, Malaya, Borneo, Vietnam but also Iraq and "our longest war – Afghanistan". "Even now, our armed forces are serving in the Middle East and elsewhere, defending the values that we hold dear. They did their duty; now, let us do ours."[26]

It seemed, then, that the Anzac Day dawn ceremonies, which an estimated 275,000 Australians attended, were a triumph for the official custodians of national memory. The record crowds could be claimed to give lie to any suggestions of commemoration fatigue and to affirm that there was an organic upswelling of nationalist sentiment "from below". In Turkey and France meanwhile the carefully choreographed transnational commemorations stood as exemplars of the "soft power" of memorial diplomacy: that is, the instrumentalization of sites of memory, commemorative events and national days as a vehicle for enhancing international relations.

Conclusion↑

However, it is the nature of hegemonic narratives that they exclude the articulation of alternative versions of events. The crowds attending Anzac Day dawn ceremonies in 2015 were certainly large, and exceeded the expectations even of the organizers; but they constituted only 1.2 percent of the Australian population of nearly 24 million. What the rest of the population thought, and thinks, about Anzac we simply do not know. The limited research available suggests that many Australians, particularly those from culturally diverse backgrounds, are disengaged from, though not hostile to, Anzac. It remains to be seen how attitudes will evolve as the excitement of the 2015 centenary ebbs and the First World War, which spawned this powerful national narrative, recedes even further into the past. It is possible that, at last, its dominance will be unsettled. But even if that should prove to be the case, the long history of Anzac and its enduring role in the Australian political culture will remain a testament to the remarkable power of the memory of the First World War and its capacity to retain a hold on the imagination of successive generations.

Joan Beaumont, Australian National University

Section Editor: Peter Stanley

Notes

- ↑ For Ashmead-Bartlett see Bretchley, Fred and Elizabeth: Myth Maker: Ellis-Ashmead-Bartlett, The Englishman Who Sparked Australia’s Gallipoli Legend, Milton 2005, pp. 86-92. For Bean, see Coulthart, Ross: Charles Bean, Sydney 2014; Rees, Peter: Bearing Witness: The Remarkable Life of Charles Bean, Australia's Greatest War Correspondent, Crows Nest 2015, ch. 14.

- ↑ Andrews, E.M: The First Anzac Day in Australia and Britain, in: Journal of the Australian War Memorial 23 (1993), pp. 13-20.

- ↑ For further detail, Cryle, Mark: Making the one day of the year: the origins of ANZAC day to 1919, PhD thesis, University of Queensland 2015.

- ↑ See Beaumont, Joan: Australia’s War 1914–18, Sydney 1996, pp. 157-159.

- ↑ Beaumont, Joan: ‘Unitedly we have fought’: Imperial loyalty and the Australian war effort, in: International Affairs, 90/2 (2014), pp. 397-412.

- ↑ Inglis, K.S.: Sacred Places, War Memorials in the Australian Landscape, Melbourne 1998, pp. 190-192.

- ↑ For the conscription debates see Beaumont, Joan: Broken Nation: Australians in the Great War, Sydney 2013, pp. 219-48, 374-89.

- ↑ Beaumont, Joan: Prisoners of War in Australian National Memory, in: Moore, Bob and Hately-Broad, Barbara (eds), Prisoners of War, Prisoners of Peace, Oxford 2005, pp. 185-94.

- ↑ Inglis, Sacred Places 1998, p. 9.

- ↑ Winter, Jay: Remembering War. The Great War between Memory and History in the Twentieth Century, New Haven 2006.

- ↑ See Beaumont, Joan: Remembering the Heroes of Australia's Wars: From Heroic to Post-Heroic Memory, in Scheipers, Sibylle (ed.): Heroism and the Changing Character of War, Basingstoke and New York, pp. 334-48; Holbrook, Carolyn: Anzac: The Unauthorised Biography, Sydney 2014.

- ↑ See Holbrook, Anzac 2014, pp. 137-142.

- ↑ Lake, Marilyn and Reynolds, Henry (eds): What’s Wrong with Anzac: The Militarisation of Australian History, Sydney 2010.

- ↑ McKenna, Mark: Anzac Day: How did it become Australia’s National Day? in: Lake, and Reynolds, What’s Wrong with Anzac 2010, pp. 110-34.

- ↑ For further details on Howard see McKenna, Mark: ‘Howard’s Warriors’, in Gaita, Raymond (ed.): Why the War was Wrong, Melbourne 2003, p. 178.

- ↑ See Lindsay, Patrick: Fromelles, Melbourne, 2008,

- ↑ For example, the National Archives of Australia’s web site, Discovering Anzacs, http://discoveringanzacs.naa.gov.au/ (retrieved 27 January 2016).

- ↑ For a full account and further references, see Beaumont, Joan: Commemoration in Australia: A memory orgy? in: Australian Journal of Political Science, 50/3 (2015), pp. 536-44.

- ↑ Department of Veterans’ Affairs: Consultation and Grants, online: http://www.dva.gov.au/consultation-and-grants/grants/approved-grants-list (retrieved 27 January 2016).

- ↑ Australians on the Western Front 1914-1918: The Australian Remembrance Trail, online: http://www.ww1westernfront.gov.au/australian-remembrance-trail/news.php (retrieved 27 January 2016).

- ↑ Miller, Nick: Tony Abbott unveils plans for new Sir John Monash Centre in France, Sydney Morning Herald, 26 April 2015, online: http://www.smh.com.au/national/ww1/tony-abbott-unveils-plans-for-new-sir-john-monash-centre-in-france-20150426-1mttau.html (retrieved 27 January 2016).

- ↑ For a critique of the commodification of the memory of war see Brown, James: Anzac’s Long Shadow, Melbourne 2014, especially pp. 16-30,120-37.

- ↑ Anzac legend ‘last hurrah of white male. The Australian, 17 March 2015, online: http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/latest-news/anzac-legend-last-hurrah-of-white-male/news-story/9198fc227e2f7dd27e3083487f3ec33a (retrieved 27 January 2016).

- ↑ See Australian War Memorial, William ‘Billy’ Sing, online. https://www.awm.gov.au/education/schools/resources/billy-sing/?query=billy+sing (retrieved 27 January 2016).

- ↑ See: My Kitchener Rules: Why aren’t Australians watching the Gallipoli miniseries? 9 March 2015,online: http://www.historypunk.com/2015/03/my-kitchner-rules-why-arent-australians.html (retrieved 27 January 2016).

- ↑ Abbott, Tony: 2015. Dawn Service Gallipoli 2015, issued by Prime Minister of Australia, online: https://www.pm.gov.au/media/2015-04-25/2015-dawn-service-gallipoli </u>(retrieved 27 May 2015).

Selected Bibliography

- Beaumont, Joan: Commemoration in Australia. A memory orgy?, in: Australian Journal of Political Science 50/3, 2015, pp. 536-544.

- Beaumont, Joan: Remembering the heroes of Australia's wars. From heroic to post-heroic memory, in: Scheipers, Sibylle (ed.): Heroism and the changing character of war. Toward post-heroic warfare?, Basingstoke 2014: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 334-348.

- Brown, James: Anzac's long shadow. The cost of our national obsession, Melbourne 2014: Black Inc..

- Holbrook, Carolyn: Anzac. The unauthorised biography, Sydney 2014: NewSouth Publishing.

- Inglis, Kenneth Stanley / Brazier, Jan: Sacred places. War memorials in the Australian landscape, Carlton 1998: Melbourne University Press.

- Lake, Marilyn / Reynolds, Henry (eds.): What’s wrong with Anzac? The militarisation of Australian history, Sydney 2010: University of New South Wales Press.

- McKenna, M.: Howard’s warriors, in: Gaita, Raimond (ed.): Why the war was wrong, Melbourne 2003: The Text Publishing Company, pp. 167-200.

- Scates, Bruce: Return to Gallipoli. Walking the battlefields of the Great War, Cambridge; New York 2006: Cambridge University Press.

- Twomey, Christina: POWs of the Japanese. Race and trauma in Australia, 1970-2005, in: Journal of War and Culture Studies 7/3, 2014, pp. 191-205.