Introduction↑

As most of the European colonial powers that held African territories became involved in the First World War as belligerents, large parts of Africa were affected by the war in one way or another. Apart from fighting in Africa and economic exploitation to support the colonial powers’ war efforts, voluntary and forced migration of soldiers and war workers to Europe was another aspect of Africa’s involvement in the war. Altogether about 440,000 indigenous soldiers, alongside 140,000 settlers of European descent and 268,000 indigenous war workers were shipped over from Africa to Europe between 1914 and 1918. This article will first outline the numbers and origins of African soldiers fighting in the armies of different European powers as well as the ways they were deployed. It then explores Africans’ war experience, its impact on colonial societies and European perceptions of African troops in the European theatres of war.

African Contingents in the French Army↑

France was the country that most extensively made use of African soldiers in European theatres of war. North African soldiers had already served in the Crimean War (1854–1856), in the 1859 Italian War and in the Franco-German War of 1870/71. Several campaigns in the immediate pre-war period had raised African colonial troops’ profile. After the first Morocco crisis in 1905/6, army general and radical politician Adolphe Messimy (1869–1935) petitioned for the extension of compulsory military service to Muslim Algerians and a 1912 decree eventually allowed for their forced recruitment if numbers of volunteers fell short of requirements. From 1909 on, colonial officer Charles Mangin (1866–1925) campaigned for a large armée noire (black army) to be recruited in West Africa and trained for deployment in European wars. He argued that demographic development would create an increasing gap between France and Germany’s available military manpower and that West Africans were especially suited to be shock troops in an industrialised war because their allegedly less developed nervous system made them immune to the noise of battle.[1] As a result, a 1912 decree allowed for forced recruitment in French West Africa and for the use of these troops outside the colony.

Between 1914 and 1918, the French deployed approximately 450,000 indigenous troops from Africa, including West Africans (so-called Tirailleurs Sénégalais), Algerians (so-called Turcos and Spahis), Tunisians, Moroccans, Malagasies, and Somalis, most of whom saw deployment in Europe. Settlers of European origin provided another 110,000 soldiers from North Africa (Chasseurs d’Afrique and Zouaves) and some of the 5,700 men in “créole” units from the old Senegalese cities and ports were also of European extraction. On the other hand, a suggestion made by Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau (1841–1929) in 1918 to hire up to 200,000 Ethiopian mercenaries never materialised.[2] Immediately after World War I French African troops would serve as occupation forces in the German Rhineland (1919 to 1930)[3] as well as in South Eastern Hungary (1919 to 1929)[4] and formed part of the Allied intervention in the Russian civil war (1918 to 1920).[5]

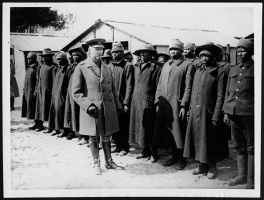

African troops in the French army, whose numbers massively increased in the second half of the war, mainly fought on the Western front and participated in all major battles there. Additionally they were deployed in the 1915 Dardanelles expedition and in the Balkans. After heavy losses in the first battles in 1914, a new doctrine for the deployment of Africans was applied. They no longer fought as independent units, but were “amalgamated” with European troops. Every regiment of the troupes coloniales (colonial troops) which were composed of Europeans, got a West African battalion. North African troops were often amalgamated into so-called régiments mixtes (mixed regiments) together with European settlers from North Africa. This doctrine also aimed at preventing the defection of Muslim soldiers to the Germans, who were using their alliance with the Ottoman Empire to pose as friends of Islam and even to recruit Muslim POWs to the Central Powers’ cause.[6] From 1917 on, with increasing numbers of African troops present at the Western Front, some of them were even incorporated into metropolitan units. Their task was most often to serve as shock troops in the first wave of attack.

Casualty figures of French African troops deployed in Europe to be found in official reports, unofficial accounts and in the historiography are rather unclear, ranging for West Africans from 25,000 to 65,000 soldiers killed, for Algerians from 12,000 to 100,000, for Moroccans from 2,500 to 9,000, and for Malagasies from 2,400 to 4,000. Figures in most recent scholarly publications typically confirm none of the extremes. These vague figures and their differing interpretation have led scholars to contradictory conclusions about whether African troops were misused as “cannon fodder.” It would be too simplistic to base any judgment of the cannon fodder thesis on global figures of killed and wounded alone, for this neglects the temporal dimension of deployment. West African troops used to be withdrawn from the front and transferred to camps in southern France during the winter months. Furthermore, the overwhelming majority of North and West Africans only came to Europe in the second half of the war. Thus, casualty rates should not be compared to overall figures of deployed soldiers, but to average figures. Joe Harris Lunn, analysing annual casualty rates of West Africans, concludes that the probability of a West African soldier being killed during his time at the front was two and a half times higher than that of a French infantryman.[7]

For many, events in 1917 lend credence to the idea that the French army used its troops from the colonies as cannon fodder. On 16 April, General Robert Nivelle (1856–1924) launched an offensive in Champagne with participation of the Second Colonial Corps (including thirty-five West African battalions) under the command of General Mangin. The German counteroffensive cost the French army dearly: almost half of all the deployed West African soldiers died. Because of this Mangin became known as the “butcher” and at the end of April he was relieved of his command. Already before this incident French soldiers interpreted the emergence of African troops as an unmistakable sign that an attack was imminent. Henri Barbusse (1873–1935), for instance, in his novel Le Feu, described Moroccan soldiers as follows: “They are imposing and even frighten a bit. [...] Of course they are heading for the front line. This is their place, and their arrival means we are about to attack. They are made for attacking.”[8]

French propaganda also developed similar themes: “From the very first hour on, African regiments had the privilege to occupy the most dangerous posts, which permitted them to enrich their book of traditions and past glory.”[9] A senior officer responsible for West Africans’ training in the camp of Fréjus wrote in a letter in January 1918 that African soldiers were “cannon fodder, who should, in order to save whites’ lives, be made use of much more intensively.”[10] And even Clemenceau, in a speech delivered to the French Senate on 20 February 1918, stated: “We are going to offer civilisation to the Blacks. They will have to pay for that [...] I would prefer that ten Blacks are killed rather than one Frenchman [...]!”[11] Thus it is clear that there was at least the intention to assign colonial troops to especially dangerous tasks as shock troops, despite scholarly controversies on the interpretation of Africans’ casualty rates as compared to Europeans’.

Africans in Other European Armies↑

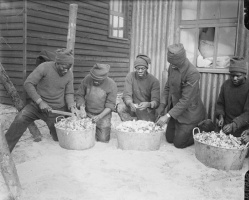

Unlike the French, the British were reluctant to deploy African troops in Europe. It is true that the British forces in the African and Middle Eastern campaigns included large numbers of African soldiers, and parts of the Indian Colonial Army were used in Europe from as early as autumn 1914 on. From 1916 on a campaign for a “million black army” following the French example was backed by several officers and politicians with colonial backgrounds, including Winston Churchill (1874–1965). But logistical issues, coupled with racist prejudices and opposition from colonial authorities in Africa, resulted in a renunciation of using such troops on European battlefields.[12] Non-white men were also banned from the “South African Overseas Expeditionary Force” that sent about 30,000 soldiers to France. Black and “coloured” men from the Union of South Africa served in Europe in the “South African Native Labour Contingent” (21,000 men), the “Cape Auxiliary Horse Transport” (2,800 men) and the “Cape Coloured Labour Corps” (1,200 men), all of them in unarmed ancillary roles.[13] However, a number of blacks resident in the United Kingdom managed to enlist in metropolitan British forces and some of them were even promoted to officer ranks.

Italy, on the other hand, tried to deploy African colonial troops in Europe which resulted in disaster. In August 1915, some 2,700 soldiers from Libya were shipped to Sicily. However, they did not enter the frontline because many soldiers died from pneumonia immediately after their arrival, and so, the Libyans, who were designated for Alpine warfare, were shipped home again after a short while. The Belgian government repeatedly discussed shipping in several thousand soldiers from the Congo, yet these plans would never materialise. Nevertheless, a small number of Congolese soldiers served on the Western front in metropolitan Belgian troops. The Portuguese didn’t deploy any colonial units in Europe either, and the number of soldiers of African descent in the metropolitan Corpo Expedicionário Português that served on the Western Front from 1916 on is unknown. The Germans, as the only colonial power amongst the Central Powers, used plenty of African soldiers of their Schutztruppen in the African theatres of war, but they had never planned to deploy these troops in Europe and would not have been able to do so during World War I for logistical reasons anyway.

African Soldiers’ War Experience and Its Impact on African Societies↑

The massive recruitment of men in North and West Africa for overseas deployment presented enormous problems. Numbers of volunteers fell short of the French army’s requirements by far and military authorities soon resorted to forced recruitment. This practice faced countless forms of opposition. In West Africa, local elites would usually try to hand over their servants to the recruiting officers in order to spare their own sons. Other forms of resistance included incidental cases of self-mutilation and fleeing into the bush or to Liberia, Gambia, Portuguese Guinea and to the Gold Coast, as well as armed rebellions against the colonial administration. A revolt in Bélédougou in 1915 undoubtedly stemmed from discontent over recruitment. During the great revolt in West Volta in 1915–16 and numerous rebellions in the north of Dahomey between 1916 and 1917 recruitment was at the very least a major trigger.[14] In Algeria, opposition occurred as well. In the autumn of 1914, potential recruits and their families protested against conscription in various locations. Resistance to recruitment culminated in the winter of 1916–17 in a major uprising in the South Constantinois.[15] In Tunisia there were a few minor revolts in 1915 and 1916.[16]

In September 1917, the Governor-General of French West Africa, Joost Van Vollenhoven (1877–1918), ordered a temporary stop to recruitment because of his concerns over the disruption of economic life. However, in spite of this, in January 1918 the French government again raised the issue of recruiting more troops in Africa. Clemenceau demanded that both French West Africa and Algeria send another 50,000 men to the Western front. The government entrusted the organisation of the recruitment in West Africa to Blaise Diagne (1872–1934). Shortly before the war, he had become the first black African elected to the French parliament and now in an unprecedented move was endowed with powers equivalent to a Governor-General. Diagne promoted military service as a means to obtain political and legal rights after the war – something that would never materialize. By September 1918, he had recruited 63,000 new soldiers in West Africa, exceeding by far the expectations of the government in Paris. The end of the war spared these soldiers from actually having to fight at the front.

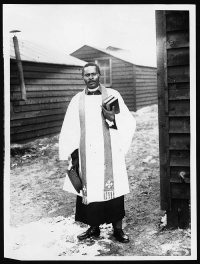

Even during World War I, and certainly ever since, observers raised questions about the impact on the colonial system of recruitment and the deployment of African troops in Europe. European fears that Africans would be revolutionised by this experience and use their newly gained confidence and military skills to turn weapons against their colonial masters were countered by the official French prophesy that service in the French army would boost Africans’ assimilation and loyalty to France and returned veterans would become agents of French civilisation in Africa. The war experience arguably had a tremendous social and cultural impact on Africans. Many veterans, especially those of servile origin, would not return to their villages after the war, but rather chose to live in the colonial cities where there were better opportunities to profit from newly gained technical skills.[17]

Three key sources for the study of African war experiences are Mohammed Ben Chérif’s (1879–1921) autobiographical novel Ahmed Ben Mostapha. Goumier,[18] Bakary Diallo’s (1892–1978) memoirs entitled Force-bonté,[19] and an extensive oral history study conducted by Joe Harris Lunn in the 1980s.[20]Ahmed Ben Mostapha was the first novel by an Algerian author to appear in French in 1920. Ben Chérif had served as a cavalry officer and become a German prisoner of war in October 1914. The hero of this first person narrative is an Algerian officer fighting in the First World War and eventually dying in a German prisoners’ camp. In this novel, Ben Chérif stressed the need for modernization of the Muslim community which was stagnating due to the adoration of its glorious past. His hero admires French culture, but at the same time is proud of being of nomadic descent.

Bakary Diallo’s memoirs were published in 1926 as the first book in French authored by a Black African. Diallo had obviously strongly adhered to French colonial ideologies. He first describes himself and his comrades as being on the same level as French children who then gradually reached the higher stages of French civilisation thanks to military service, until they were completely assimilated and started even to dream in French. Diallo’s war experience, however, differed from that of most of his comrades in several respects. He had volunteered for the French army as early as 1911, so he did not experience the forced conscription between 1914 and 1917 that traumatised West African populations. Diallo’s front experience was not representative either as he was only there for a relatively short time. Already on 3 November 1914, he was wounded and afterwards promoted. He earned a distinction for bravery and was even granted French citizenship in 1920. After the war, he would remain in France until 1928.[21]

Thanks to Lunn’s oral history study, we are also informed about the war experience of a larger group of West Africans. Lunn interviewed eighty-five Senegalese veterans (about half of the veterans still living at that time) in 1982/83. His book shows that important cultural changes in Franco-Senegalese relations took place in the years from 1914 to 1918. Some West Africans would no longer perceive the French as almighty “devils” as many of them had done before. This would promote their self-confidence in the post-war period. The veterans’ understanding of their European experience, however, obviously was not uniform. Some of the veterans interviewed by Lunn believed that the war did not have any notable impact on their country while others emphasized an alleged causality between their war service and post-war change or even Senegal’s independence four decades later on.

African ego-documents analysed in existing studies largely represent hindsight perspectives. This makes it difficult to reconstruct African soldiers’ perceptions of Europe and the Europeans at the time. We can only speculate that they followed similar patterns as the Indian soldiers’ (for which research has analysed extensive amounts of letters) whose confrontation with Europe and Europeans show a variety of responses and coping mechanisms: some were able to assimilate European mores and habits with their cultural background, some rejected their own customs and habits and formed an unconditional admiration for the European social, economic and gender order, while another group tried to defend their cultural identity and meet their religious duties and traditional roles as men and warriors.[22] European perceptions of African soldiers, on the other hand, can be reconstructed more easily.

European Perceptions↑

The presence of hundreds of thousands of African soldiers on European soil was also a crucial event for Europeans and attracted widespread attention. European images of African soldiers evolved in different ways on both sides of the Western front. In Germany, representation developed along the lines of racist pre-war imagery, even reaching the extremes of representing colonial soldiers as beasts. In summer 1915, the German Foreign Office put into circulation a pamphlet entitled Employment, Contrary to International Law, of Colored Troops in the European Theatre of War by England and France, in which many atrocities were attributed to colonial soldiers such as poking out the eyes and cutting off the ears, noses and heads of wounded and captured German soldiers.[23] In German propaganda, colonial troops were labelled with all sorts of racist expressions that negated their quality as regular military forces. Even the liberal sociologist Max Weber (1864–1920) complained that “an army of niggers, Ghurkhas and all the barbarians of the world” were at Germany’s borders.[24]

Another recurrent theme in German propaganda against the deployment of African troops in Europe was its alleged impact on the future of the colonial system and the supremacy of the “white race.” If African soldiers were trained in the handling of modern arms, if they were brought to Europe and saw the “white” nations fighting against each other, and if they were even allowed to participate in these battles and experience the vulnerability of the white man, then they would lose their respect once and forever. After the war, they would turn their weapons against their own masters and destroy colonial rule. However, German propaganda against the use of African troops in Europe would climax only after 1918, when the presence of colonial soldiers in the French zone of occupation triggered a highly racist campaign against the “Black horror on the Rhine.”

The stories of atrocities circulated by the German propaganda apparently also reached the front which did nothing to improve the morale of the troops. Statements in soldiers’ letters like, “you can’t really consider a nigger [...] as a comrade”[25] bear witness to their contempt for Africans as illegitimate opponents. Thus, it was generally believed the Africans took no prisoners and when German units captured a new sector of the front, the question was often anxiously put as to whether there were any black soldiers among the opponents. A German army report of 1918 stated that a column “quickly abandoned the front line without a shot having been fired and without the enemy appearing at the cry of ‘The French are attacking, the blacks are coming.’”[26]

Entente propaganda countered German propaganda within the patterns of pre-World War argumentation, albeit with some modifications. In the first months of the war, representations of colonial troops in the French press did not differ much from German propaganda images. Two weeks after the outbreak of the war, the Dépêche Coloniale portrayed African soldiers as démons noirs (black demons) who would carry over the Rhine, with their bayonets, the revenge of civilization against modern barbarism.[27] Beginning in 1915/16, officials propagated a modified image of infantile and devoted savages. African soldiers were depicted as belonging to races jeunes (young races) and as absolutely obedient to the white masters because of the latter’s intellectual supremacy. Therefore, they were a danger neither to white supremacy in the colonial world, nor to the French metropolitan population.

This propaganda was also produced to calm the French population’s reservations about the African troops’ presence in France. Large parts of the French population seem to have shared the image of Africans as bloodthirsty savages. When the first West African units arrived in France, large crowds welcomed them shouting, “Bravo les tirailleurs sénégalais! Couper têtes aux allemands!” (“Well done, Senegalese tirailleurs! Chop the Germans’ heads!”)[28] This image also stirred a latent popular opposition to stationing African soldiers in Southern France. The French military administration also promoted the image of primitive savages. For instance, African soldiers were given boots from the French arsenals that were far too big for them, as their feet were supposed to have enormous dimensions because of permanent barefoot walking. As late as in 1917, there was a proposal that West African soldiers should fight barefoot because, with French boots, “those agile apes are losing one of their best infantry qualities, namely their elasticity in marching.”[29]

Civilians’ encounters with African soldiers, both in France during the war and in the French zone of occupation in Germany after the war, were manifold. French writer and painter Lucie Cousturier (1876–1925), who had gotten to know a number of injured West African soldiers while she nursed them during and after the war, wrote in her 1920 book Des Inconnus chez moi about the original mood among the civilian population in Southern France:

However, there were also numerous friendly encounters between African soldiers and French civilians and love and sex across the colour line were by no means unheard of.[31] The same is true for the relationship between German civilians and Africans troops during the Rhineland occupation.[32]

But how did European Entente soldiers perceive their African comrades? The letters and memoirs of French and British soldiers show an ambivalent attitude. Most soldiers were curious about these “exotic” soldiers and some even sympathised with them. At the same time, evidence also shows that African soldiers were not considered to be equal comrades, but rather auxiliaries for especially dangerous tasks. Louis Barthas (1879–1952), cooper, trade unionist and socialist, described an Algerian division he encountered at Narbonne as “magnifique” (magnificent), but also felt sorry for them.[33] Second lieutenant Roland Leighton (1895–1915) in a letter also referred to North African troops: “They all look very Negroid, but are well built men and march well.”[34] At the same time, ideas about Africans’ alleged brutality lingered on. Thus, in Le Feu Barbusse, who had spent eleven months at the front, referred to the Moroccan soldiers as “devils” who are used to “poking the bayonet in the enemy’s belly.”[35] Furthermore, some French soldiers were also concerned about the alleged use of African troops against (mainly female) workers on strike and about the sexual threat raised by the proximity of colonial men to French women.

Conclusion↑

African military participation on European battlefields between 1914 and 1918 was a crucial experience both for Africans and Europeans. Never before had so many Africans temporarily migrated to Europe in such a short period of time. The experience of forced recruitment, traveling to Europe, and fighting in a war very few could have imagined left deep marks not only on surviving and returning veterans, but also on African societies in general. However, the presence of hundreds of thousands of Africans in Europe also had important effects upon Europeans. Despite reinforcing discourses of colonial racism, it also created cultural encounters of a different sort. The question of whether the deployment of African troops in Europe tightened or loosened colonial bonds that would attract historians’ interest for decades to come thus has no simple answer. Many veterans after the war would (as the French war propaganda had predicted) be closer to the colonial administration and serve as middlemen between the colonizers and the colonized. On the other hand, although the great uprising against colonial rule that had been predicted by the German war propaganda as a result of colonial soldiers’ experience of war in Europe would not materialize, wartime recruitment had triggered several local rebellions and participation in the war effort had raised Africans’ expectations of political reform as a reward.

Christian Koller, Universität Zürich

Section Editors: Melvin E. Page; Richard Fogarty

Notes

- ↑ See Mangin, Charles Marie Emmanuel: Troupes noires, in: Revue de Paris 16 (1909), pp. 387-388.

- ↑ See Poincaré, Raymond: Au service de la France. Neuf années de souvenirs, volume 10, Paris 1933, pp. 14-15; Watson, David Robin: Georges Clemenceau: A Political Biography, Plymouth 1974, p. 307.

- ↑ See Reinders, Robert C.: Racialism on the Left. E. D. Morel and the “Black Horror on the Rhine,” in: International Review of Social History 13 (1968), pp. 1-28; Nelson, Keith S.: Black Horror on the Rhine. Race as a factor in post-World War I diplomacy, in: Journal of Modern History 42 (1970), pp. 606-627; Marks, Sally: Black Watch on the Rhine. A study in propaganda, prejudice and prurience, in: European Studies Review 13 (1983), pp. 297-333; Lebzelter, Gisela: Die “Schwarze Schmach.” Vorurteile – Propaganda – Mythos, in: Geschichte und Gesellschaft 11 (1985), pp. 37-58; Koller, Christian: “Von Wilden aller Rassen niedergemetzelt.” Die Diskussion über die Verwendung von Kolonialtruppen in Europa zwischen Rassismus, Kolonial- und Militärpolitik (1914–1930), Stuttgart 2001; Le Naour, Jean-Yves: La honte noire. L'Allemagne et les troupes coloniales françaises, 1914–1945, Paris 2003; Wigger, Iris: Die “Schwarze Schmach am Rhein.” Rassistische Diskriminierung zwischen Geschlecht, Klasse, Nation und Rasse, Münster 2006; Kettlitz, Eberhardt: Afrikanische Soldaten aus deutscher Sicht seit 1871. Stereotype, Vorurteile, Feindbilder und Rassismus, Frankfurt et al. 2007; Martin, Peter: Die Kampagne gegen die "Schwarze Schmach" als Ausdruck konservativer Visionen vom Untergang des Abendlandes, in: Höpp, Gerhard (ed.): Fremde Erfahrungen. Asiaten und Afrikaner in Deutschland, Österreich und in der Schweiz bis 1945, Berlin 1996, pp. 211-224; Martin, Gregory: German and French Perceptions of the French North and West African contingents, 1910–1918, in: Militärgeschichtliche Mitteilungen 56 (1997), pp. 31-68; Campt, Tina et al.: Germans, and the Politics of Imperial Imagination, 1920–1960, in: Friedrichsmeyer, Sara et al. (eds.): The Imperialist Imagination. German Colonialism and Its Legacy, Ann Arbor 1998, pp. 205-229; Lunn, Joe Harris: "Les Races Guerrières." Racial Preconceptions in the French military about West African Soldiers during the First World War, in: Journal of Contemporary History 34 (1999), pp. 517-536; Nagl, Tobias: “Die Wacht am Rhein.” “Rasse” und Rassismus in der Filmpropaganda gegen die “schwarze Schmach” (1921–1923), in: Hertzfeld, Hella / Schäfgen, Katrin (eds.): Kultur, Macht, Politik. Perspektiven einer kritischen Wissenschaft, Berlin 2004, pp. 135-154; Roos, Julia: Women’s Rights, Nationalist Anxieties, and the “Moral” Agenda in the Early Weimar Republic. Revisiting the “Black Horror” Campaign against France’s African Occupation Troops, in: Central European History 42 (2009), pp. 473-508; Collar, Peter George: German Propaganda against the French Occupation of the Rhineland 1919–1924. Agencies, Personalities and Themes, PhD dissertation, University of London 2011; Van Galen Last, Dick: De Zwarte Schande. Afrikaanse Soldaten en Europa [The Black Shame. African Soldiers in Europe], 1914–1922, Amsterdam 2012.

- ↑ See Martonyi, Eva: L'image du Tirailleur Sénégalais dans la littérature hongroise, in: Riesz, Jànos / Schultz, Joachim (eds.): "Tirailleurs sénégalais." Zur bildlichen und literarischen Darstellung afrikanischer Soldaten im Dienste Frankreichs, Frankfurt am Main et al. 1989, pp. 171-181.

- ↑ See Kommunisticheskie listovki i vozzvaniia k soldatam antanty [Communist leaflets and appeals to the Entente soldiers], in: Istoricheskii Archiv 1 (1958), pp. 38-39; Seleznev, K. L.: Revoliutsionnaia rabota bol'shevikov v vojskach interventov (1918–1919 gg.) [The Bolsheviks’ revolutionary work during the intervention wars, 1918–1919)], in: Istoriia SSSR 1 (1960), pp. 125-137; Munholland, Kim: The French Army and Intervention in the Ukraine, in: Pastor, Peter (ed.): Revolutions and Interventions in Hungary and its Neighbor States, 1918–1919, New Jersey et al. 1988, p. 347.

- ↑ See e. g. Höpp, Gerhard: Die Privilegien der Verlierer. Über Status und Schicksal muslimischer Kriegsgefangener und Deserteure in Deutschland während des Ersten Weltkrieges und in der Zwischenweltkriegszeit, in: Höpp, Gerhard (ed.): Fremde Erfahrungen. Asiaten und Afrikaner in Deutschland, Österreich und in der Schweiz bis 1945, Berlin 1996, pp. 185-210; Müller, Herbert Landolin: Islam, ğihad ("Heiliger Krieg") und Deutsches Reich, Frankfurt am Main 1991, pp. 267-298.

- ↑ Lunn, Joe Harris: Memoirs of the Maelstrom. A Senegalese Oral History of the First World War, Portsmouth et al. 1999, pp. 140-147.

- ↑ Barbusse, Henri: Le Feu. Journal d'une escouade, Paris 1916, pp. 48-49.

- ↑ Boussenot, Georges: La France d'outre-mer participe à la guerre, Paris 1916, p. 43.

- ↑ Cited in Michel, Marc: L'appel à l'Afrique. Contributions et réactions à l'effort de guerre en A.O.F., Paris 1982, p. 323.

- ↑ Cited in Ageron, Charles-Robert: Clemenceau et la question coloniale, in: Wormser, André (ed.): Clemenceau et la justice. Actes du colloque de décembre 1979 organisé pour le cinquentenaire de la mort de G. Clemenceau, Paris 1983, p. 80.

- ↑ See Killingray, David: The Idea of a British Imperial African Army, in: Journal of African History 20 (1979), pp. 421-436.

- ↑ See Nasson, Bill: Springbocks on the Somme: South Africa in the Great War 1914–1918, Johannesburg 2007; Garson, N.G.: South Africa and World War I, in: Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 8 (1979), pp. 68-85; Grundlingh, Albert: Fighting their own war. South African Blacks and the First World War, Johannesburg 1987; Willan, B. P.: The South African Native Labour Contingent 1916–1918, in: Journal of African History 19 (1978), pp. 61-86.

- ↑ See Garcia, Luc: Les mouvements de resistance au Dahomey (1914–1917), in: Cahiers d'Études Africaines 10 (1970), pp. 144-178; Gnankambary, Blamy: La révolte bobo de 1916 dans le cercle du Dedougou, in: Notes et Documents voltaïques 3 (1970), pp. 56-87; Hébert, Jean: Révoltes en Haute Volta de 1914 à 1918, in: Notes et Documents voltaïques 3 (1970), pp. 3-54; D'Almeida-Topor, Hélène: Les populations dahoméens et le recrutement militaire pendant le première guerre mondiale, in: Revue française d'histoire d'outre-mer 60 (1973), pp. 196-241; Michel, L'appel à l'Afrique 1982, pp. 50-57, 100-116, 118-120, 127-130.

- ↑ See Ageron, Charles-Robert: Les Algériens musulmans et la France, 1871–1919, 2 vols., Paris 1968, pp. 1142-1157; Meynier, Gilbert: L'Algérie révélée. La guerre de 1914–1918 et le premier quart du XXe siècle, Geneva 1981, pp. 569-598.

- ↑ See Lejri, Mohammed-Salah: L'histoire du mouvement national, volume 1, Tunis 1974, pp. 157-163.

- ↑ See Lunn, Memoirs 1999; Mann, Gregory: Native Sons: West African Veterans and France in the Twentieth Century, Durham 2006.

- ↑ Ben Chérif, Mohammed: Ahmed Ben Mostapha. Goumier, Paris 1920.

- ↑ Diallo, Bakary: Force-Bonté, Paris 1926.

- ↑ Lunn, Memoirs 1999; Lunn, Joe Harris: Kande Kamara Speaks: An Oral History of the West African Experience in France 1914–18, in: Page, Melvin E. (ed.): Africa and the First World War, London 1987, pp. 28-53.

- ↑ See on Diallo Midiohouan, Guy Ossito: Le tirailleur sénégalais du fusil à la plume. La fortune de "Force-Bonté" de Bakary Diallo, in: Riesz, Jànos / Schultz, Joachim (eds.): "Tirailleurs sénégalais." Zur bildlichen und literarischen Darstellung afrikanischer Soldaten im Dienste Frankreichs. Frankfurt am Main et al. 1989, pp. 133-151; Riesz, Jànos: The Tirailleur Sénégalais Who Did Not Want to Be a "Grand Enfant." Bakary Diallo's Force Bonté (1926) Reconsidered, in: Research in African Literatures 27 (1996), pp. 157-197; Riesz, Jànos: Die Probe aufs Exempel. Eine afrikanische Autobiographie als Zivilisations-Experiment, in: Willems, Herbert / Hahn, Alois (eds.): Identität und Moderne, Frankfurt 1999, pp. 433-454.

- ↑ See Vankoski, Susan C.: Letters Home, 1915–16: Punjabi Soldiers Reflect on War and Life in Europe and their Meanings for Home and Self, in: International Journal for Punjab Studies 2 (1995), pp. 43-63; Omissi, David: Europe through Indian Eyes: Indian Soldiers Encounter England and France 1914–1918, in: English Historical Review 122 (2007), pp. 371-396; Omissi, David (ed.): Indian Voices of the Great War: Soldiers' Letters, 1914–18, London 1999; Koller, Christian: Überkreuzende Frontlinien? Fremdrepräsentationen in afrikanischen, indischen und europäischen Selbstzeugnissen des Ersten Weltkrieges, in: War and Literature 6 (2000), pp. 33-57; Koller, Christian: Krieg, Fremdheitserfahrung und Männlichkeit: Alterität und Identität in Feldpostbriefen indischer Soldaten des Ersten Weltkrieges, in: Bos, Marguérite et al. (eds.): Erfahrung – Alles nur Diskurs? Zur Verwendung des Erfahrungsbegriffes in der Geschlechtergeschichte, Zurich 2004, pp. 117-128; Koller, Christian: Representing Otherness: African, Indian, and European soldiers’ letters and memoirs, in: Das, Santanu (ed.): Race, Empire and First World War Writing, Cambridge 2011, pp. 254-285; Koller, Christian: Wartime Europe as seen by others: Indian and African soldiers in Europe in WW1, in: Pinheiro, Teresa et al. (eds..): Ideas of / for Europe: An Interdisciplinary Approach to European Identity, Frankfurt 2012, pp. 516-528.

- ↑ Auswärtiges, Amt (ed.): Employment, Contrary to International Law, of Colored Troops in the European Theatre of War by England and France, Berlin 1915.

- ↑ Weber, Max: Russlands Übergang zur Scheindemokratie, in: Hilfe 23 (1917), p. 279.

- ↑ Witkop, Philipp (ed.): Kriegsbriefe gefallener Studenten, Munich 1928, p. 26.

- ↑ Bundesarchiv-Militärarchiv N 87/7 80. Reserve-Division, 12.10.1918 (Abschrift).

- ↑ La Dépêche Coloniale, 18 August 1914.

- ↑ Cited in Diallo, Force-Bonté 1926, p. 113.

- ↑ Mangin, Charles: L'utilisation des Troupes Noires, in: Revue de Paris 24 (1917), p. 882.

- ↑ Cousturier, Lucie: Des Inconnus chez moi: Tirailleurs Sénégalais, Paris 1920, pp. 12-13.

- ↑ See Stovall, Tyler: The Color Line behind the Lines. Racial Violence in France during the Great War, in: American Historical Review 103 (1998), pp. 737-769.

- ↑ See Koller, Christian: “Afrika am Rhein.” Zivilbevölkerung und Kolonialtruppen im rheinischen Besatzungsgebiet der 1920er Jahre, in: Kronenbitter, Günther / Pöhlmann, Markus / Walter, Dierk (eds.): Besatzung. Funktion und Gestalt militärischer Fremdherrschaft von der Antike bis zum 20. Jahrhundert, Paderborn et al. 2006, pp. 105-117.

- ↑ Barthas, Louis: Les carnets de guerre de Louis Barthas, tonnelier 1914–1918, Paris 1997, pp. 21-22.

- ↑ Bishop, Alan / Bostridge, Mark (eds.): Letters from a lost generation. The First World War letters of Vera Brittain and four friends, London 1998, p. 128.

- ↑ Barbusse, Le Feu 1916, pp. 48-49.

Selected Bibliography

- Balesi, Charles John: From adversaries to comrades-in-arms. West Africans and the French military, 1885-1918, Waltham 1979: Crossroads Press.

- Bekraoui, Mohammed: Les Marocains dans la Grande Guerre 1914-1919, Rabat 2009: Commission marocaine d’histoire militaire.

- Clarke, Peter B.: West Africans at war, 1914-18, 1939-45. Colonial propaganda and its cultural aftermath, London 1986: Ethnographica.

- Das, Santanu (ed.): Race, empire and First World War writing, Cambridge; New York 2011: Cambridge University Press.

- Dendooven, Dominiek / Chielens, Piet (eds.): World War I. Five continents in Flanders, Tielt 2008: Lannoo.

- Devantour, Paul / Pradel de Lamaze, Jean de: L'Armée d'Afrique dans la guerre 1914-1918 et les campagnes d'après-guerre (1918-1939), in: Huré, Robert (ed.): L'Armée d'Afrique, 1830-1962, Paris 1977: Charles-Lavauzelle, pp. 263-319.

- Echenberg, Myron J.: Colonial conscripts. The Tirailleurs Sénégalais in French West Africa, 1857-1960, Portsmouth; London 1991: Heinemann; J. Currey.

- Fogarty, Richard: Race and war in France. Colonial subjects in the French army, 1914-1918, Baltimore 2008: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Galen Last, Dick van / Futselaar, Ralf: De zwarte schande. Afrikaanse soldaten in Europa, 1914-1922 (The black shame. African soldiers in Europe), Amsterdam 2012: Atlas Contact.

- Grundlingh, Albert M.: Fighting their own war. South African Blacks and the First World War, Johannesburg 1987: Ravan Press.

- Kamian, Bakari: Des tranchées de Verdun à l'église Saint-Bernard, Paris 2001: Karthala.

- Killingray, David: The idea of a British Imperial African army, in: The Journal of African History 20/03, 1979, pp. 421-436.

- Koller, Christian: 'Von Wilden aller Rassen niedergemetzelt.' Die Diskussion um die Verwendung von Kolonialtruppen in Europa zwischen Rassismus, Kolonial- und Militärpolitik (1914-1930), Stuttgart 2001: Steiner.

- Koller, Christian: The recruitment of colonial troops in Africa and Asia and their deployment in Europe during the First World War, in: Immigrants and Minorities 26/1-2, 2008, pp. 111-133.

- Levine, Philippa: Battle colors. Race, sex, and colonial soldiery in World War I, in: Journal of Women's History 9/4, 1998, pp. 104-130.

- Liebau, Heike / Bromber, Katrin / Lange, Katharina et al. (eds.): The world in world wars. Experiences, perceptions and perspectives from Africa and Asia, Leiden 2010: Brill.

- Lunn, Joe Harris: 'Les Races Guerrieres'. Racial preconceptions in the French military about West African soldiers during the First World War, in: Journal of Contemporary History 34/4, 1999, pp. 517-536.

- Lunn, Joe Harris: Memoirs of the maelstrom. A Senegalese oral history of the First World War, Portsmouth; Oxford; Cape Town 1999: Heinemann; J. Currey; D. Philip.

- Martin, Gregory: German and French perceptions of the French North and West African contingents, 1910–1918, in: Militärgeschichtliche Zeitschrift 56/1, 1997, pp. 31-68.

- Melzer, Annabelle: Spectacles and sexualities. The 'Mise-en-Scène' of the 'Tirailleur Sénégalais' on the Western Front, 1914–1920, in: Melman, Billie (ed.): Borderlines. Genders and identities in war and peace, 1870-1930, New York 1997: Routledge, pp. 213-244.

- Meynier, Gilbert: L'Algérie révélée. La guerre de 1914-1918 et le premier quart du XXe siècle, Geneva 1981: Droz.

- Michel, Marc: L'appel à l'Afrique. Contributions et réactions à l'effort de guerre en A.O.F. (1914-1919), Paris 1982: Publications de la Sorbonne.

- Nasson, Bill: Springboks on the Somme. South Africa in the Great War, 1914-1918, Johannesburg; New York 2007: Penguin.

- Page, Melvin E. (ed.): Africa and the First World War, New York 1987: St. Martin's Press.

- Rathbone, Richard: World War I and Africa. Introduction, in: The Journal of African History 19/01, 1978, pp. 1-9.

- Riesz, János / Schultz, Joachim (eds.): 'Tirailleurs sénégalais'. Zur bildlichen und literarischen Darstellung afrikanischer Soldaten im Dienste Frankreichs, Frankfurt a. M.; New York 1989: Lang.

- Rives, Maurice / Dietrich, Robert: Héros méconnus, 1914-1918, 1939-1945. Mémorial des combattants d'Afrique noire et de Madagascar, Paris 1993: Association française Frères d'armes.

- Winegard, Timothy C.: Indigenous peoples of the British dominions and the First World War, New York 2011: Cambridge University Press.